Bonus 7: SCOTUS's Top 10 (Non-Merits) Stories of 2022

Recaps of the Court's Terms (or years) tend to focus on the Justices' substantive rulings. Here, I take a look at 10 big 2022 stories *besides* those decisions

Welcome to this week’s “One First” bonus content, a preview of which is available to all subscribers, with the full content available to paid subscribers. (Monday’s regular issue will always be free to all subscribers.)

It seems de rigueur to end the year with some kind of “Top 10” list (or I just watched too much David Letterman growing up). Either way, I thought I’d use this week’s bonus content to do a Top 10 SCOTUS list for 2022 with a bit of a twist. Any account of the Top 10 SCOTUS stories of 2022 would be dominated by some of the Court’s biggest rulings—Dobbs; Bruen; West Virginia v. EPA; the religion cases; the OSHA/CMS vaccine mandate cases; etc.

But what if we took the merits out of it, and looked at the top 10 non-merits SCOTUS stories of 2022? Not only do I think such a list tells a meanigfully different story about the Court, but it also reinforces one of my broader goals in this newsletter—to provide a holistic view of the Court as an institution, and not just a reactive view of the Court as the sum of its rulings.

With that in mind, here’s my unofficial Top 10 list of big 2022 SCOTUS stories other than the substance of its 58 decisions in cases argued during the October 2021 Term, reactions to which will likely sort many (if not most) into their usual camps:

10. To Mask or Not To Mask

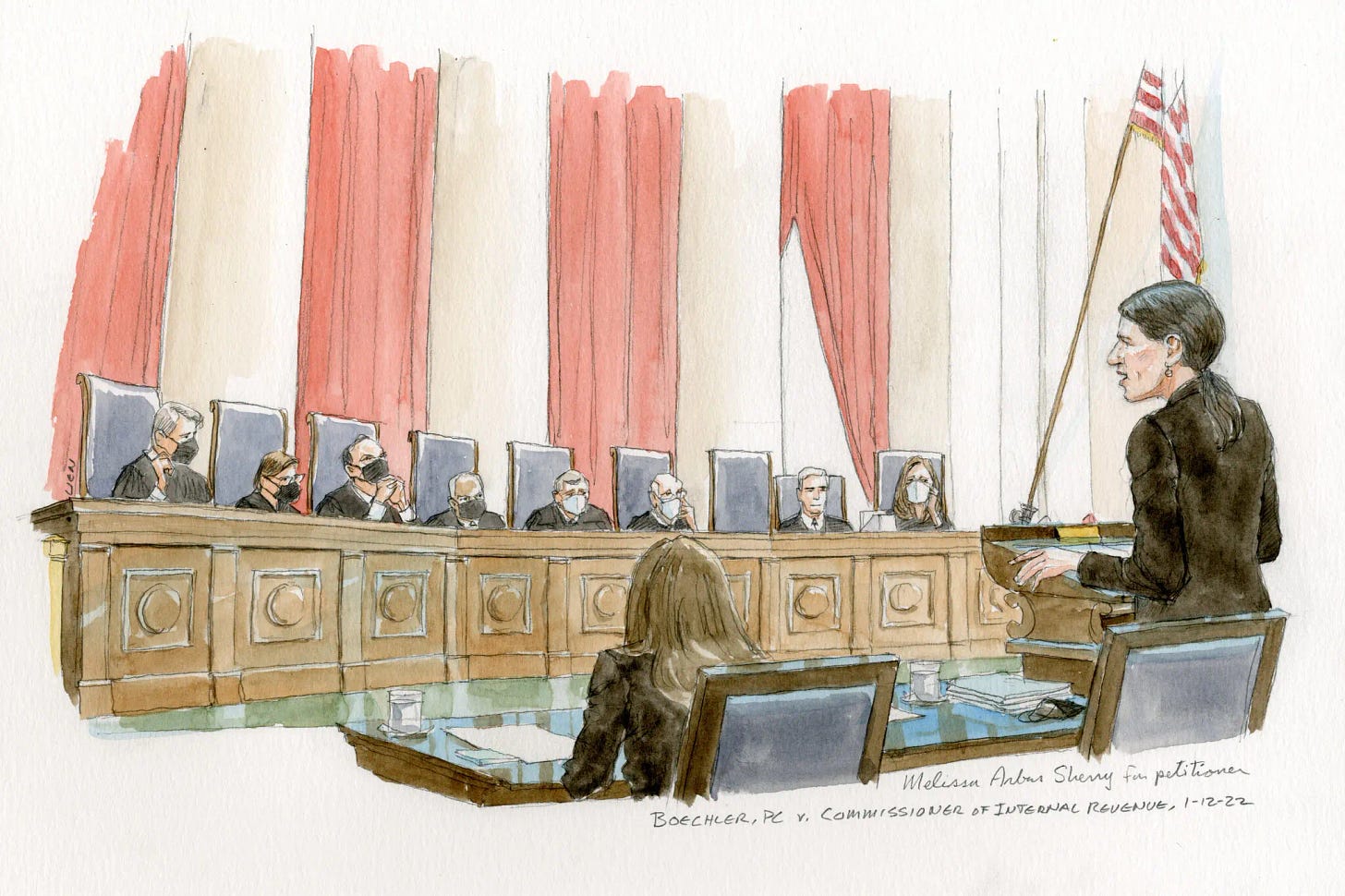

The year began with a bang—in the midst of the Omicron surge, the Court heard oral argument on a pair of emergency applications relating to Biden administration vaccine mandates, the first such arguments (on emergency applications) since the early 1970s. All of the Justices showed up for the arguments wearing a mask except Justice Gorsuch, with Justice Sotomayor participating remotely. That set off … a whole thing (with Nina Totenberg reporting that the Chief Justice had asked everyone to mask up on the bench, and that Sotomayor chose to participate remotely after it became clear Gorsuch wouldn’t), culminating in one of the most awkward, non-responsive joint statements in the history of the Court. And that was January.

9. Financial Disclosure … Corrections

Not one, not two, but three of the nine Justices (Thomas, Sotomayor, and Jackson) had to update or otherwise correct prior financial disclosure reports during calendar year 2022—in each case, to include income that had not previously been reported. This should’ve been a bigger story.

Fortunately, Gabe Roth and his colleagues at Fix the Court have been on it. But the laxity surrounding these statements, including how often the Justices miss the filing deadlines, ought to be a bigger deal (and one of many subjects of potential congressional reforms).

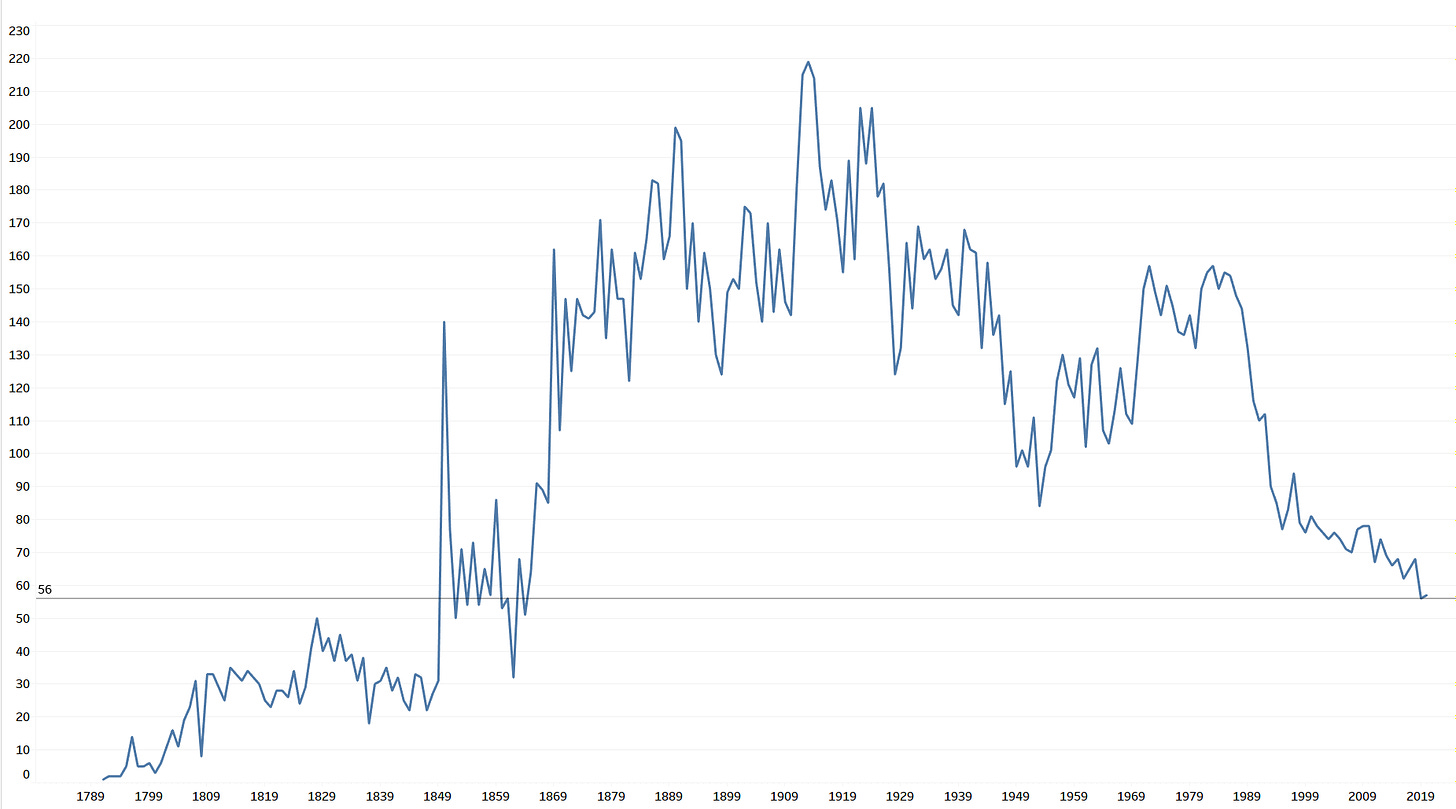

8. The Shrinking Docket

Although the flurry of high-profile decisions in June might have given a different impression, the Court handed down only 58 signed decisions in argued cases during the October 2021 Term—the third-lowest total since the Civil War. The second-lowest was the October 2020 Term; the lowest was the October 2019 Term. Here’s a helpful graphic by Dr. Adam Feldman depicting the significant constriction of the merits docket in the last few years:

Reasonable minds will differ about why the Court is deciding so few cases these days, and whether that’s a good or a bad thing. At some point, though, it sure seems increasingly clear that it’s a thing.

7. Ginni Thomas and January 6

News reports that Virginia (“Ginni”) Thomas, the wife of Justice Clarence Thomas, had exchanged text messages with White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows in the run up to January 6 (and, later, the messages themselves) ignited a firestorm about her involvement in efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election and, in a related vein, Justice Thomas’s participation in cases relating to the January 6 investigation (including the Court’s rejection of an emergency application from President Trump trying to block the National Archives and Records Administration from turning over certain documents to the January 6 Committee, from which Thomas was the lone public dissenter).

Ginni Thomas ended up agreeing to sit for an interview with the January 6 Committee, during which she apparently reasserted her belief that the 2020 election was stolen from Trump, and also told the Committee that she and Justice Thomas have “an ironclad rule” that they never speak about matters pending before the Supreme Court.

If nothing else, the controversy reignited a long-running debate over whether the Justices should be subject to the Code of Conduct for United States Judges (they are not at present); and whether the federal disqualification statute, which does apply to the Justices, needs a better enforcement mechanism than self-policing by individual members of the Court.

6. The Court and the Midterms

There’s a lot to say about the Court’s impact on the midterms, and political scientists might be saying it for a while. But there were at least three seats in the House in which the Court played a direct role—in all three cases almost certainly giving Republicans a safe seat that could just as easily have been a safe seat for Democrats. That’s because of the Court’s unsigned and unexplained orders in Merrill v. Milligan and Ardoin v. Robinson, which allowed Alabama and Louisiana, respectively, to use congressional district maps that lower courts had struck down.

In both cases, lower courts had ordered the state to draw an additional “majority-minority district,” one that would almost certainly have been a safe Democratic seat. By allowing both states to use the invalidated maps, the Justices not only kept in place seats that were safe for Republicans; they also led a district judge in Georgia to decline to block Georgia’s maps after finding a similar violation of the Voting Rights Act. In the end, the Republicans will have a 222-212 majority on January 3 (with a special election for the vacant seat from Virginia’s Fourth District set for February). But had as few as three races come out differently, control of the House could well have turned on those two orders.

5. The Uncorrected Error in Shinn v. Ramirez

A few years ago, the Court began the (laudable if overdue) practice of publicly noting when revisions (including corrections) were made to opinions after they were released (on the same page to which opinions are posted). But one of the stranger moments of the Term came when the Court doubled-down on what was more than just a typographical error in the majority opinion in Shinn v. Ramirez.

Specifically, in a dispute about post-conviction habeas relief, Justice Thomas’s majority opinion stated that “Respondents do not dispute, and therefore concede, that their habeas petitions fail on the state-court record alone.” As the respondents noted in a rare “motion to modify opinion,” no such concession had been made. More than that, Arizona agreed with the respondents that the statement was erroneous and should be modified. And yet, the Court denied the motion—with no explanation. The whole episode was unusual, but the denouement was … inexplicable.

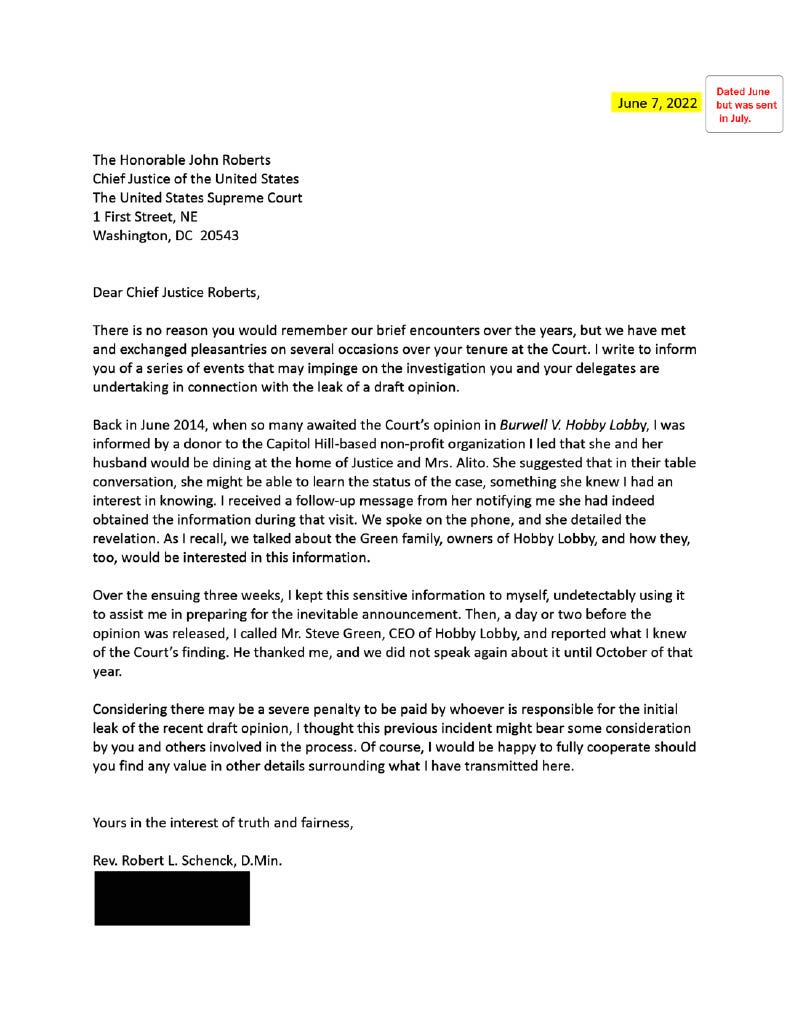

4. Hobby Lobby-Gate

Perhaps because we’d spent much of the summer discussing the biggest leak in the Supreme Court’s history (more on that below), there was perhaps a bit more muted reaction to a major New York Times story from November, reporting that Justice Alito had divulged the outcome (and his authorship) of the 2014 decision in Hobby Lobby v. Burwell to private dinner companions months beforehand.

There’s quite a lot to say about the story. There have also been questions raised about the credibility of almost everyone involved (my favorite is the dinner guest who now claims that the information that she could only relay by telephone and not over e-mail was that Justice Alito volunteered to drive her and her husband home). But to me, the bigger point here isn’t whether or not Alito leaked the result or authorship; it’s the amount of access that these folks had (and, by all accounts, still have) to the Justices in contexts in which they clearly have an agenda relating to the outcomes of individual cases, regardless of what the Justices think.

3. The Legitimacy Roadshow

Continuing a pattern we saw in 2021, 2022 also saw a series of remarkable public speeches and other comments by the Justices reflecting on the Court’s legitimacy (and its potential erosion). In September alone, there was a crazy sequence in which Chief Justice Roberts and then Justice Kagan gave conflicting accounts of the Court’s legitimacy in speeches to different audiences, only to have Justice Alito respond by giving the Wall Street Journal a quote that included what was clearly a public shot at Kagan: “It goes without saying that everyone is free to express disagreement with our decisions and to criticize our reasoning as they see fit. But saying or implying that the court is becoming an illegitimate institution or questioning our integrity crosses an important line.”

Again, how folks react to this story will likely align to a large degree with their priors. But leaving aside how unusual (or ugly) it is for the Justices to be taking these kinds of shots at each other in their public remarks, one point that ought not to be controversial is the lack of transparency surrounding these public comments. If you take a look at the Supreme Court’s webpage devoted to providing copies of the Justices’ public speeches, the last entry is from … Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. In 2019.

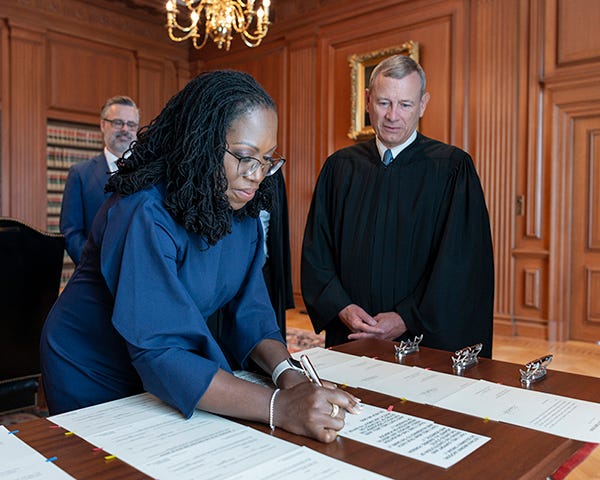

2. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson

In any other year, the confirmation of a new Justice, let alone the first Black woman in the Court’s history, would run away with first on the list. As it is, the confirmation of Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, who was sworn in on June 30 as the 116th Justice, was an enormous deal, whether or not it altered the center of ideological gravity on the Court.

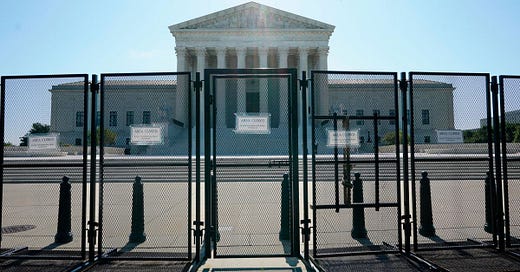

1. The Leak

Nearly eight months after the most stunning leak in the Court’s history, there’s been no illumination for the public about who leaked to reporters for Politico the draft of Justice Alito’s majority opinion in Dobbs. The leak was (and remains) staggering not just for what it was and what it portended, but for what happened next. There were follow-on leaks (including stunningly brazen leaks to the media about things that were said at the Justices’ private conference); there were unhinged efforts by conservatives to blame then-serving clerks for the more liberal Justices (one of whom was publicly accused of being the leaker based upon … non-evidence); there were stepped-up security measures (and protests outside of some of the Justices’ homes); there was the attempted assassination of Justice Kavanaugh (and the remarkable letters by the Court’s Marshal imploring local officials to more aggressively enforce Maryland’s and Virginia’s limits on protests); and the list keeps going.

Everyone will have their own pet theories about who leaked the draft and why (my own remains that it was a second-degree leak—that a Justice shared a draft with a close personal friend who, without the Justice’s permission, leaked it to the press). But the one point on which there ought to be consensus is that this was simply a stunning moment for the Court as an institution—one that has already had, and will have, lots of effects, virtually none of which are good.

It’ll be interesting to see whether, in his Year-End Report on the Federal Judiciary (due out Saturday at 6 p.m. ET), Chief Justice Roberts says anything to acknowledge the unique … challenges … the Supreme Court faced in 2022. But hopefully this Top 10 list helps to put into context just how many remarkable stories involving the Court took place in 2022 that go beyond the major rulings the Justices handed down.

[Cue Paul Shaffer.]

I hope you enjoyed this week’s bonus content—and, if you did, I hope you’ll recommend that others consider a paid subscription to the newsletter.

I’ll be back Monday for our regular weekly installment, this one focusing on the Chief Justice’s forthcoming year-end report. Happy New Year, all; here’s to a peaceful and prosperous 2023!

As for the vaccine mandates, the latest science shows the jab wasn't so great, even from the very beginning: https://okaythennews.substack.com/p/science-summary-covid-19-vaccines

Great read.