Bonus 62: What the Heck is Happening Along the Rio Grande?

The Supreme Court has a chance to bring some clarity to the legal situation along the U.S.-Mexico border. Leaving matters unsettled risks exacerbating an already problematic situation.

Welcome back to the weekly bonus content for “One First.” Although Monday’s regular newsletter will remain free for as long as I’m able to do this, much of the bonus content is behind a paywall to help incentivize those who are willing and able to support the work that goes into putting this newsletter together every week. I’m grateful to those of you who are already paid subscribers, and hope that those of you who aren’t will consider a paid subscription if your circumstances permit:

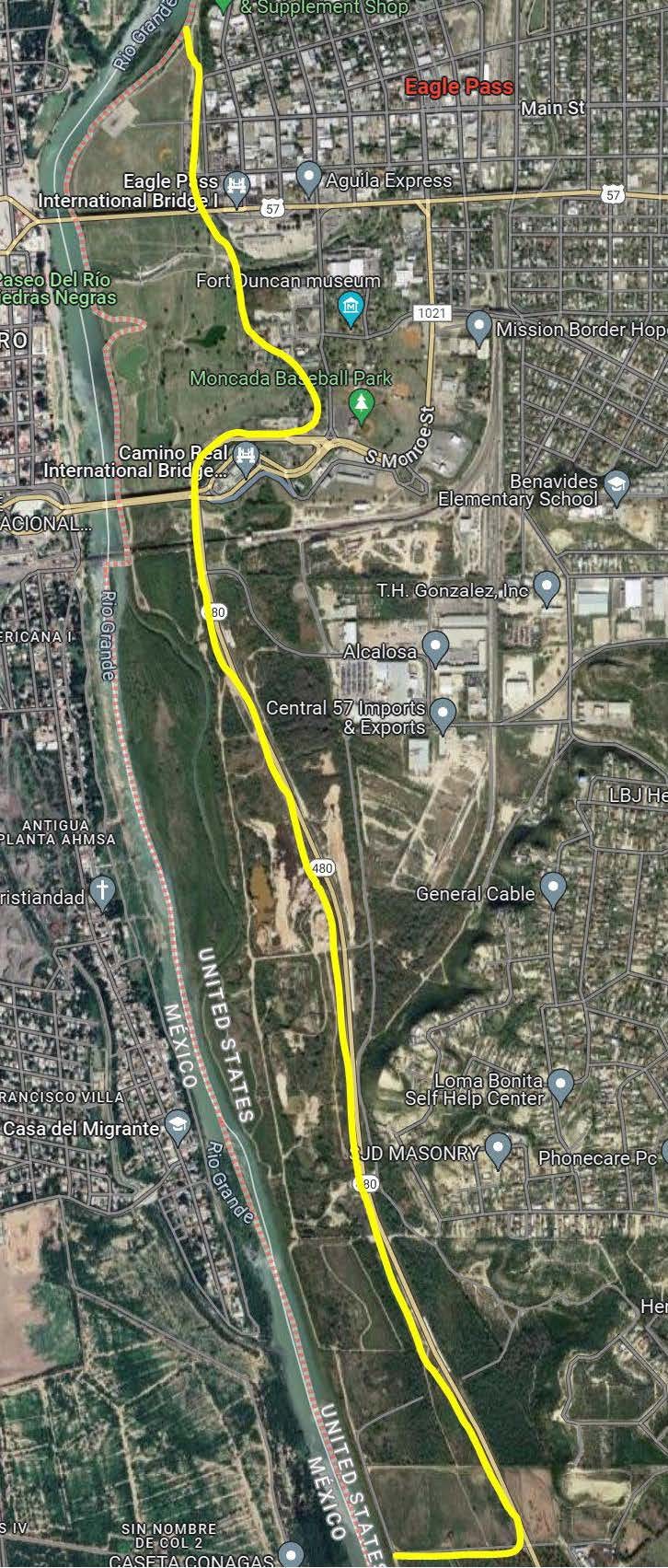

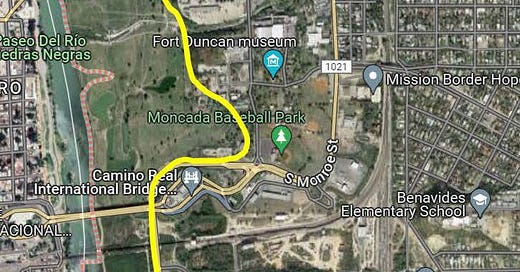

For this week’s bonus content, I wanted to take a shot at providing an overview of the legal situation along the U.S.-Mexico border in Texas, especially in and around Eagle Pass, after a bunch of headlines over the weekend about Texas’s refusal to allow federal authorities to have access to a 2.5-mile stretch of the Rio Grande (and contested claims that this refusal might have helped to prevent the rescue of migrants who drowned while trying to cross the river).

To make a long story short(er), there are three different lawsuits, at different stages, between the federal government and Texas arising out of Texas’s current activities. One of them has an emergency application from the Biden administration pending in the Supreme Court; another had a significant ruling from the Fifth Circuit just come down yesterday. And the sooner the justices clarify exactly what Texas can and can’t do to supplant (if not frustrate) federal immigration authorities, the better—lest the situation on the ground escalate even further. Reasonable (and less reasonable) minds will continue to disagree about what makes the most sense with regard to the future of U.S. immigration policy. But a world in which armed officers of a state and the federal government are heading toward what could well be an effective standoff with each other is one that we should all be invested in avoiding.

For those who are not paid subscribers, the next free installment of the newsletter will drop on Monday morning. For those who are, please read on.

At the heart of these cases is “Operation Lone Star,” a multi-year effort led by Texas Governor Greg Abbott to take as much control over law enforcement along the U.S.-Mexico border in Texas as possible—part of an effort to deter those seeking to enter the United States from doing so along the 1,254-mile-long stretch of the border in Texas. Throughout much of the “Operation,” Abbott and other Texas officials have claimed that they’re exercising their federal constitutional right to defend themselves against “invasion” (of would-be immigrants) in a context in which the federal government is, in their view, failing to fulfill its constitutional obligation to “protect” states. (Leaving aside the problem of letting individual states decide for themselves what counts as an “invasion” for purposes of Article IV, § 4, I don’t think an upsurge in unauthorized border crossings is what the Founders had in mind.)

For a time, Operation Lone Star was focused on aggressive use of the Texas National Guard and state law enforcement just inside the border. But since the middle of last year, those efforts have escalated dramatically to include more operations along the border. For instance, Texas officials placed a series of red floating barriers in the middle of the Rio Grande near the town of Eagle Pass (which, if you know at all, you might recognize as one of the key locations in the Cormac McCarthy book-turned-movie, No Country for Old Men), all in an effort to make it harder for migrants to try to cross the river and enter the United States at what had been one of the more popular unauthorized crossing points.

Not long after, Texas officials also began placing “concertina” wire (a form of razor wire) on private property along various stretches of (and near) the border—also as a mechanism to deter efforts to enter the country near Eagle Pass. Federal officials started cutting or otherwise destroying some of the razor-wire barriers, both because they were inhibiting federal immigration enforcement and because they threatened serious bodily injury to migrants—until they were enjoined from doing so by the Fifth Circuit (more on that below).

While all of this was happening, the Texas legislature passed, and Governor Abbott signed into law, “SB4,” which creates a series of new state crimes and state enforcement authorities related to federal immigration enforcement. (I wrote about some of the many constitutional problems with the bill last month for MSNBC.)

Finally, last Thursday, Texas seized control of, and put up fencing around, Shelby Park—a large recreational area abutting the border in Eagle Pass (and adjacent to one of Eagle Pass’s two ports of entry), which federal authorities had previously used as a staging area for policing and interdiction operations along the Rio Grande (among other things, there’s a large boat ramp in Shelby Park that federal authorities had been relying upon for river access). Thus, there has been a slow-but-steady escalation in the efforts by Texas to not just assume control over immigration along that stretch of the border, but to affirmatively thwart efforts by federal officials to assert their own authority.

These actions have precipitated a number of lawsuits. Three, in particular, have been between the federal government and Texas.

The first, unhelpfully captioned United States v. Abbott, was brought by the Department of Justice and is focused on the movable barriers in the Rio Grande—and the federal government’s claim that they violate section 10 of the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899, which bars anyone other than the federal government from erecting obstacles in “waters of the United States” without the federal government’s permission. (Texas’s principal response is that section 10 doesn’t apply because that portion of the Rio Grande isn’t “navigable.”) On September 6, the district court sided with the federal government and entered a preliminary injunction ordering Texas to move the barriers out of the river. Texas appealed, but a 2-1 panel affirmed on December 1. Texas then sought rehearing en banc. Just yesterday, the Fifth Circuit granted rehearing en banc, vacating the panel opinion. The full court is now set to hear oral argument in May.

The second, no more helpfully captioned Texas v. U.S. Dep’t of Homeland Security, was a suit by Texas against the federal government, arguing that the destruction of razor wire by federal officials was a tort under Texas state law. Although the district court initially granted a temporary restraining order, it ultimately refused to issue a preliminary injunction—holding that the federal government likely has sovereign immunity from such a tort suit (while chastising the Biden administration for its policy choices).

Texas appealed, and sought an injunction pending appeal. On December 19, a three-judge panel granted the emergency relief Texas sought, albeit only after wrongly equating an injunction pending appeal to a stay (as I wrote about last week). It’s from that ruling that the Biden administration has sought emergency relief in the Supreme Court, asking the justices to vacate that injunction pending appeal. Even though Texas filed its response to the application on January 9, that application remains outstanding. (And it’s with respect to that application that there were a flurry of additional filings over the weekend and earlier this week relating to Texas’s seizure of Shelby Park.)

Finally, the United States has also sued Texas seeking to prevent most of SB4 from going into effect—on the ground that its central provisions are all preempted by federal law, and the authorities Congress has given to the federal government in such cases. That lawsuit, also unhelpfully captioned United States v. Texas, was filed on January 3 in Austin, and is still in its preliminary stages (the federal government has moved for a preliminary injunction, with briefing underway and a hearing scheduled for February 13).

My own view, which likely won’t come as a surprise to readers of this newsletter, is that the federal government ought to win all three of these cases. The barrier case (United States v. Abbott) turns on the meaning of a 125-year-old statute, but I think the panel majority has the better of the analysis as to why Texas’s conduct likely violates that statute. (That’s not good for much before the full Fifth Circuit, but it ought to matter when the dispute reaches the Supreme Court.) Among other things, it’s hard to imagine that Congress wasn’t thinking about rivers that also serve as international borders when it conditioned efforts to place obstructions in those rivers on federal approval. Critically, though, it’s going to take awhile. The en banc Fifth Circuit isn’t going to hear argument until May, which likely means no decision until at least late this summer. And presumably the federal government will be in the position of having to appeal that ruling to the Supreme Court sometime next term.

The SB4 case (United States v. Texas) is not just a rehash of Arizona v. United States (the big 2012 Supreme Court decision rejecting a comparable effort by Arizona to claim authority over various aspects of immigration enforcement); the Texas bill goes even further in intruding into federal prerogatives than Arizona’s “SB1070,” as I laid out in my MSNBC column. Yes, this is a very different Supreme Court than the one that decided Arizona. But it ought to resonate even with justices more sympathetic to Texas than I am that, if they let Texas take over large swaths of immigration enforcement during a Democratic administration, they risk comparable efforts by the Californias of the world during a Republican administration. Again, though, this case is not moving with particular dispatch. Even if the district court moves fairly quickly to grant a preliminary injunction after the February 13 hearing, that will inevitably provoke not just an appeal from Texas, but also a request for emergency relief from the Fifth Circuit pending that appeal. That, too, likely won’t play out until at least late in the spring.

That leaves the concertina-wire case, Texas v. U.S. Department of Homeland Security. That’s the one before the Supreme Court now, and it’s one in which the Solicitor General has gone out of her way to flag the escalatory nature of Texas’s behavior—including a remarkable brief filed after 1:30 a.m. ET last Friday morning about Texas’s seizure of Shelby Park and its consequences. The underlying legal dispute—whether states can bring ordinary tort suits against the federal government to prevent federal officers from carrying out their law enforcement responsibilities—is remarkably contrived; the federal government’s general immunity from tort liability is among those points of law on which every justice agrees. There’s also the related but distinct point that, to obtain an injunction pending appeal, Texas was supposed to have to show that its right to relief is “indisputably clear.” Alas.

And although there’s significant dispute about exactly what happened this past weekend, there’s no dispute that Texas has been, and still is, restricting at least some access to the Rio Grande in ways that the Justice Department claims are interfering with federal officials’ ability to police the border. Allowing the federal government to cut or otherwise remove concertina wire that is preventing it from actually carrying out federal immigration policy seems like, and ought to be, a relatively easy lift for the justices—and yet the lack of a ruling to this point suggests some amount of division (and perhaps separate opinions being drafted) behind the scenes.

The larger point, though, is that there is no sign that Texas is going to stop its behavior anytime soon—and so it may behoove the justices, whether in the concertina-wire case or elsewhere, to more clearly demarcate exactly what states can and can’t do when it comes to supplementing (and, increasingly, supplanting) federal immigration enforcement. The alternative is to leave these issues unresolved (with Speaker Johnson pouring cold water on statutory immigration reform), or, at least up to the Fifth Circuit. But that seems only to be leading us toward ever more troubling conflicts, if not confrontations, between federal and state officials in and around Eagle Pass—perhaps the most aggressive such contretemps since federal troops were sent to enforce desegregation decrees in recalcitrant states in the 1950s and 1960s.

Indeed, such confrontations might be good politics for Governor Abbott and others who are opposed to the current administration’s immigration policies (who can “win” even by losing), but they’re very bad for (and as) constitutional law. As Justice Robert Jackson wrote for the Supreme Court in 1954, courts “cannot resolve conflicts of authority by our judgment as to the wisdom or need of either conflicting policy. The compact between the states creating the Federal Government resolves them as a matter of supremacy. However wise or needful [a state’s] policy, . . . it must give way to the contrary federal policy.” Otherwise, our “federal” system would be one in name only.

It might be time for the Supreme Court to remind Texas of this point.

We’ll be back Monday with our regular coverage of the Court. Until then, thanks for reading; I hope you have a great weekend!

Do you think that Abbot and buds actually BELIEVE that border crossings are an "invasion?" Or is this all just whupping up the voters?

Rep. Cellar has suggested federalizing the Texas National Guard. Believe that is part of what Eisenhower did with the Arkansas Guard in Little Rock.