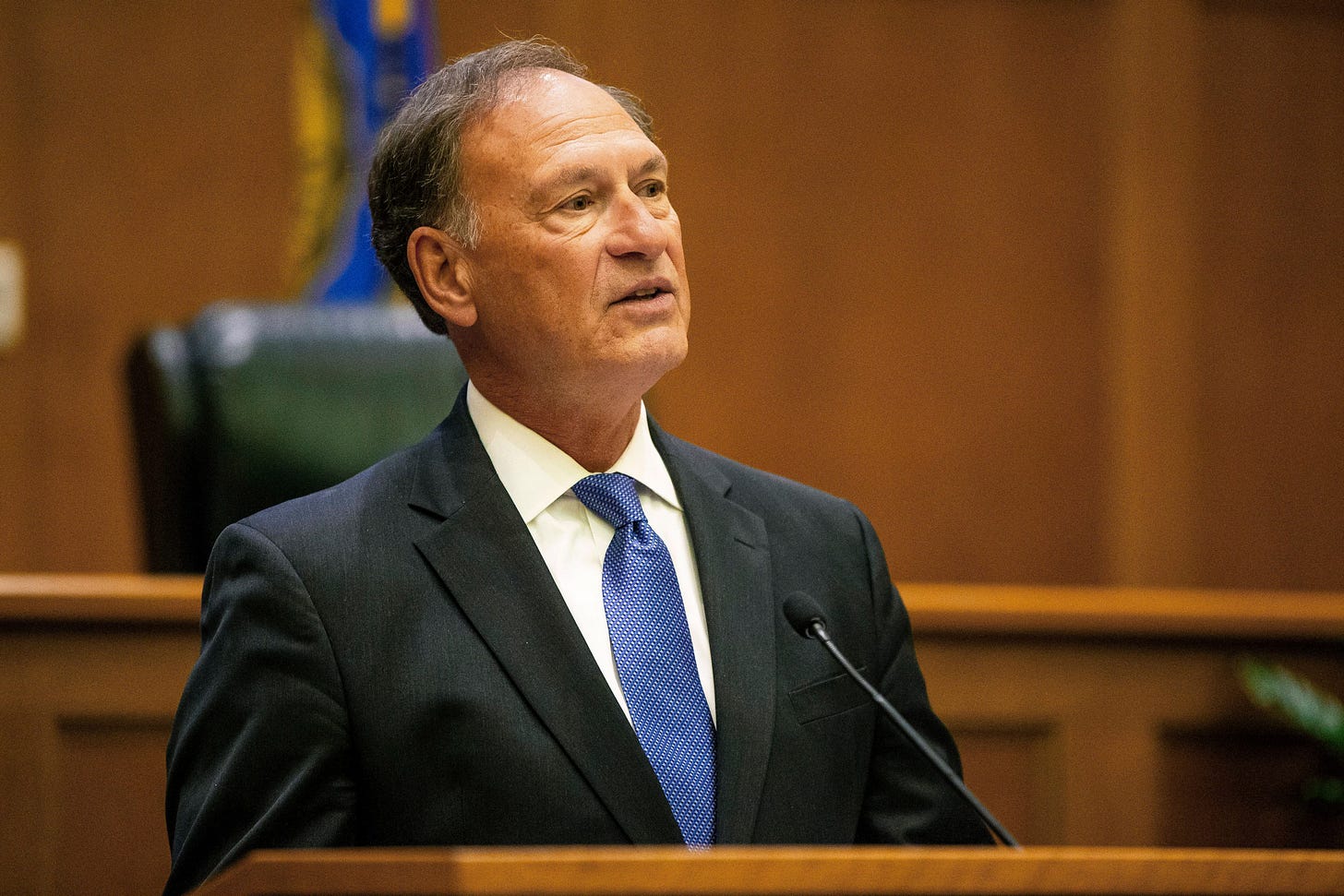

Bonus 38: Justice Alito and the Separation of Powers

Justice Alito's assertion that Congress's lacks the power to regulate the Court is clearly wrong as a matter of constitutional text, historical practice, and common sense. So why'd he make it?

Welcome back to the weekly bonus content for “One First.” Although Monday’s regular newsletter will remain free for as long as I’m able to do this, much of Thursday’s content is behind a paywall to help incentivize those who are willing and able to support the work that goes into putting this newsletter together every week. I’m grateful to those of you who are already paid subscribers, and hope that those of you who aren’t will consider a paid subscription if your circumstances permit:

One of the central distinctions between the substance of Monday’s free issues and that of Thursday’s bonus content is the personalization of the latter. To that end, I wanted to use today’s installment to reflect on Justice Alito’s latest “interview,” published last Friday afternoon in the Wall Street Journal. In another “conversation” with two conservative allies (one of whom, it ought to be noted, is one of the lawyers in a major case currently pending before the Supreme Court), Alito touched on a wide range of topics. But perhaps the most extraordinary claim in the piece came toward the end—in response to the possibility of Congress adopting some kind of ethics reforms for the justices. Quoting Alito, “I know this is a controversial view, but I’m willing to say it. . . . No provision in the Constitution gives them the authority to regulate the Supreme Court—period.”

This claim is not just “controversial”; it’s utterly wrong as a matter of constitutional text, longstanding historical practice, and even the most basic understanding of the separation of powers. But worse than all of those flaws, as I explain below the fold, is the fact that Justice Alito had no problem making this point in this context in the first place. It wasn’t off the cuff; this was in a carefully controlled setting in which he would necessarily have had a chance to edit and review the piece before it was published. As someone who regularly complains about commentary from critics that, in his view, undermines public confidence in the Supreme Court, Justice Alito comes off like the guy in the hot dog suit: “We’re all trying to figure out who did this.”

For those who are not paid subscribers, the next free installment of the newsletter will drop Monday morning. For those who are, please read on.

Let’s start with what Justice Alito gets (badly) wrong. It’s simply not true that “no provision in the Constitution gives [Congress] the authority to regulate the Supreme Court.” At least three of them do just that. Most expressly, the Exceptions Clause of Article III, Section 2 specifically defines the Supreme Court’s appellate jurisdiction (in contrast to its original jurisdiction) as existing only “with such exceptions, and under such regulations as the Congress shall make.” In other words, before getting to anything else, Congress has the express power to “regulat[e]” the Court’s appellate jurisdiction (which, as I noted on Monday, is now the overwhelming majority of the Court’s substantive work).

Second, there’s also Congress’s power under the Necessary and Proper Clause “To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.” It is this latter power that has allowed Congress to regularly exercise statutory control over, among other things:

The size of the Court (including Congress’s expansion of the Court, in 1837, to create the very seat that Justice Alito currently occupies);

Where the Court sits (which, until 1935, was literally in the Capitol);

When the Court meets (including Congress’s effective cancellation of the Court’s entire 1802 Term);

The Court’s budget (the Constitution prevents Congress only from reducing the justices’ salaries; it says nothing about any other feature of the justices’ pay or the Court’s overall budget);

The justices’ travel (including the requirement, abandoned only at the end of 1911, that the justices literally “ride circuit” and travel around the country to hear cases as circuit judges);

The justices’ retirement and pensions (which are not protected by the Constitution); and

One of the two oaths the justices are required to take.

And even in the specific context of ethics, Congress has, over time, subjected the justices, as such, to an array of reporting and recusal requirements. Of course, Justice Alito may believe that those requirements (some of which date as far back as 1974) are unconstitutional; the relevant point for present purposes is that these are longstanding (and constitutionally grounded) precedents for congressional “regulation” of the Court and the justices.

Of course, Congress’s regulatory powers are not unlimited; I, for one, think that there are constitutional limits on Congress’s power over the Supreme Court’s appellate jurisdiction. And, further to last week’s discussion of United States v. Klein, I don’t think Congress could use these powers to effectively compel a specific result in a specific case. But there’s an enormous difference between debating the outer bounds of Congress’s well-settled power to regulate the Court and claiming that no such power exists in the first place.

And then there’s Congress’s third power over the Court: the power to impeach justices who are not engaging in “good behavior.” Because the Constitution does not itself define “good behavior,” that term effectively means whatever a majority of the House and two-thirds of the Senate decide that it means. As I noted in an early issue of this newsletter, the Senate set an important early precedent for limiting the impeachment of justices in 1805—but no one disputes that it was for the Senate to set that precedent in the first place. In that respect, the Constitution expressly empowers the legislature to police the justices’ behavior by empowering it to remove justices whose behavior is sufficiently poor. It’s hard to understand the argument that an express and uncontested constitutional power to impeach and remove those who fail to engage in “good behavior” does not imply a lesser power to set standards (and reporting requirements) for what good behavior is (and isn’t). Indeed, wouldn’t we prefer a world in which Congress defined “good behavior” up front, rather than in the midst of a contentious impeachment proceeding?

In any event, what a lot of the public reaction to Alito’s comments misses is how Congress has historically used all of these powers—as leverage. Congress’s control of things like the Court’s jurisdiction and budget was, for much of the Court’s first 150 years, a means by which Congress exerted authority over the Court and its decisionmaking. To take two examples, Congress in 1964 cut the justices out of most of a pay raise that it approved for every other federal judge—entirely to express displeasure with some of the Court’s recent rulings. It used its constitutional authority as a cudgel—a means of exerting itself (and its opposition to recent decisions by the justices) to “punish” the Court. Ditto the elimination of the 1802 Term to which I alluded above—a technical amendment that was understood, then and since, as a not-so-subtle warning from the Jeffersonian-controlled Congress to the Federalist-controlled Court to leave intact the reforms adopted in the Judiciary Act of 1802. (And closer to home, even the specter of impeachment unquestionably helped to push Justice Fortas to resign in 1969.)

So even if one wants to quibble with the word “regulate” (but see the plain text of the Exceptions Clause), the historical reality is one in which Congress, at least until recently, was routinely resorting to each of its powers over the Court to play its part, both formally and informally, in a robust interbranch conversation about the work of the Court and the behavior of the justices. Not only is that undeniable from the historical record; it was, in my view, a good thing. As James Madison put it in Federalist No. 51, “ambition must be made to counteract ambition.” In that vein, Congress and the Court kept each other in check by using their respective powers to keep the other from getting too far out of line. That understanding may have broken down in recent years, but that’s more about the politics of the current moment than it is about any fundamental shift in constitutional interpretation and understanding.

Nor is this understanding unique to the judicial branch. Any history of the interbranch relationship between Congress and the executive reflects a profoundly similar story—in which Congress regularly has used, and uses, its powers over the executive branch to influence, both directly and indirectly, the actions of the President and his subordinates. Everything from the power of the purse to the creation of inspectors general to impeachment—levers for the legislature to pull. As with the Court, some of those attempts went too far (and were reined in by the justices). But those are marginal cases; the heartland of the American model of the separation of powers is interbranch assertions of oversight and control, not branches that are hermetically sealed from one another.

Justice Alito may not like this textual and historical structure for the separation of powers, but he’s hardly oblivious to it. Indeed, before he was first appointed to the federal bench in 1990, Alito had spent 13 years as a lawyer in the executive branch—as a federal prosecutor; as an assistant to the Solicitor General; and as a deputy assistant AG in the Office of Legal Counsel, a role in which these kinds of separation of powers debates would have regularly played a big part.

But if Justice Alito knows all of this, why make such a knowingly incorrect and deliberately provocative statement? Perhaps the answer is to fire up his (and the Court’s) defenders, many of whom may not be as … well-informed? Or to empower Republican members of Congress to point to his public statements as support for their own opposition to ethics reform legislation (such as the bill that made it out of the Senate Judiciary Committee on a party-line, 11-10 vote)? After all, if Justice Alito says it’s unconstitutional, the constitutional objections must at least be per se reasonable, no? (No.)

Only Justice Alito knows his motives. I’ll just say here that, even if his impulse was to provide fodder for his (and the Court’s) supporters, that seems to radically undervalue the damage it does to his (and the Court’s) credibility to so publicly take such a nihilistic view about the separation of powers.

It is a simple, ineluctable, and constitutionally compelled fact that the Court can’t function without the political branches, on which it depends not just for the enforcement of its judgments, but for the far more basic requirements of turning on the lights. For Justice Alito to use the fraught context of a friendly “interview” with staunch conservative allies (one of whom, again, has a case pending before the Court) to suggest that the Court is constitutionally above even the most basic principles of interbranch accountability is for him to reinforce the very criticisms at which he is putatively chafing—and to make the case, far better than his critics ever could, for the very accountability reforms to which he is so vocally objecting.

We’ll be back Monday with our usual coverage of the Court. Until then, thanks for reading; I hope you have a great weekend!

If Kagan had done the same thing, the howls from the Journal editorial page would have been heard in space.

The short answer is because he could. Having said that, notwithstanding the significance of his assertion, there are other aspects of the interview that are equally if not more extraordinary in terms of his very specific and open criticism of other justices, both those commonly aligned with his views and those that are not, that is quite surprising and I suspect do not sit well with his colleagues.