Bonus 145: How (We Think) Emergency Applications Work

Given how much of the Supreme Court's work in recent years (okay, days) has been focused on emergency applications, it seemed worth attempting an explainer on how (we think) they're handled.

Welcome back to the weekly bonus content for “One First.” Although Monday’s regular newsletter (and unscheduled issues) will remain free for as long as I’m able to do this, I put much of Thursday’s bonus content behind a paywall as an added incentive for those who are willing and able to support the work that goes into putting this newsletter together every week. I’m grateful to those of you who are already paid subscribers, and I hope that those of you who aren’t will consider a paid subscription if and when your circumstances permit.

Given last weekend’s late-night drama respecting the ACLU’s (still-pending) emergency application in one of the Alien Enemy Act cases, it seemed worth taking a step back and providing a more holistic overview—for both new subscribers and folks who have been here longer—of the process by which emergency applications are filed and decided. One of this newsletter’s very first posts, back in 2022, introduced the different ways in which the Supreme Court decides cases (and the difference between “opinions” and “orders”). But (1) I assume that most of those who have subscribed since then haven’t seen it; and (2) in any event, that post doesn’t walk carefully through what we know (and what we suspect) about how the justices actually process emergency applications internally, about which we’ve learned at least a little in the ensuing 2.5 years. Hence, today’s post.

One big caveat before diving in: Very little about the Court’s internal processes here are publicly memorialized … anywhere. I’ll do my best to differentiate between what we know and what we think (and, for the latter, why we think that). But a fair amount of what follows below the fold reflects informed speculation (and what we generally believe to be norms), rather than hard-and-fast rules that can be publicly referenced. There’s a non-pejorative reason why University of Chicago Professor Will Baude dubbed the output of the Court’s internal processes in these cases (and others) “the shadow docket.”

Introduction: What is an “Application”?

“Emergency” applications are just a subset of all of the applications that are filed with the Supreme Court (everything that gets docketed with a “yyAnnnn” docket number, like “24A1007”).1

Most applications fall into one of four categories:

An application for relief from a procedural rule: The most common version of this is an application for an extension of time within which to file a cert. petition (i.e., an appeal). By rule, a litigant has 90 days from the date of the relevant lower-court decision to file, but by statute, the deadline is 150 days. Thus, individual justices can (and often do) grant extensions (of up to 60 days) when parties request them. Applicants might also ask to be allowed to file a brief in excess of the word limits set by the Court’s rules, or to otherwise depart from other of those rules for good cause shown. These applications, which represent an overwhelming majority of the total number of applications the Court receives each term, are seldom contested, and are, in virtually every case, resolved by a single justice (more on that below).

An application for “emergency” relief from a lower court order: The second most common type of application by volume (comprising around 7.5–10% of all applications), these are what a lot of folks think is the entire “shadow docket,” and not just one part of one subset thereof.2 That misunderstanding aside, it’s certainly the most important type of application. In these contexts, the applicant is asking for much more than what they’re seeking in the first category: they’re asking the Circuit Justice (or the full Court) to either suspend the effect of a lower-court ruling or, even more aggressively, to themselves freeze a defendant’s conduct, while the broader litigation challenging that conduct works its way through the legal system.

An application for bail or a “certificate of appealability”: Both of these are largely anachronistic, but individual justices, by statute, have the power to grant bail to federal prisoners seeking to be released from custody while they challenge their conviction and/or sentence; and to grant a “certificate of appealability” to state or federal prisoners seeking permission to file a second-or-successive post-conviction challenge to their conviction or sentence. Because of statutory reforms that have limited the circumstances in which any federal court can grant these, and because of the ability of lower courts to provide such relief in virtually any case in which a justice could, these are seldom filed, and virtually never granted.3

An application respecting the Court’s judgment and mandate: Whereas the first three categories of applications all come before further action by the Court, this one comes only after the Court has completed plenary review and issued a ruling, and usually is related to that ruling. So, for instance, when a dispute arose over the lower court to which the Supreme Court should remand its decision in the Texas abortion ban case in 2021, the plaintiffs filed an application seeking to have the mandate issued immediately, and to have the case remanded to the district court rather than the Fifth Circuit. The only notable procedural difference is that, unlike the first three categories of applications (which go to the geographically appropriate “Circuit Justice”), applications seeking this kind of relief are directed (by the Court) to the justice who authored the majority opinion (in that case, Justice Gorsuch—who agreed to issue the judgment immediately, but remanded the case to the Fifth Circuit, not the district court).

Filing an Application with the “Circuit Justice”

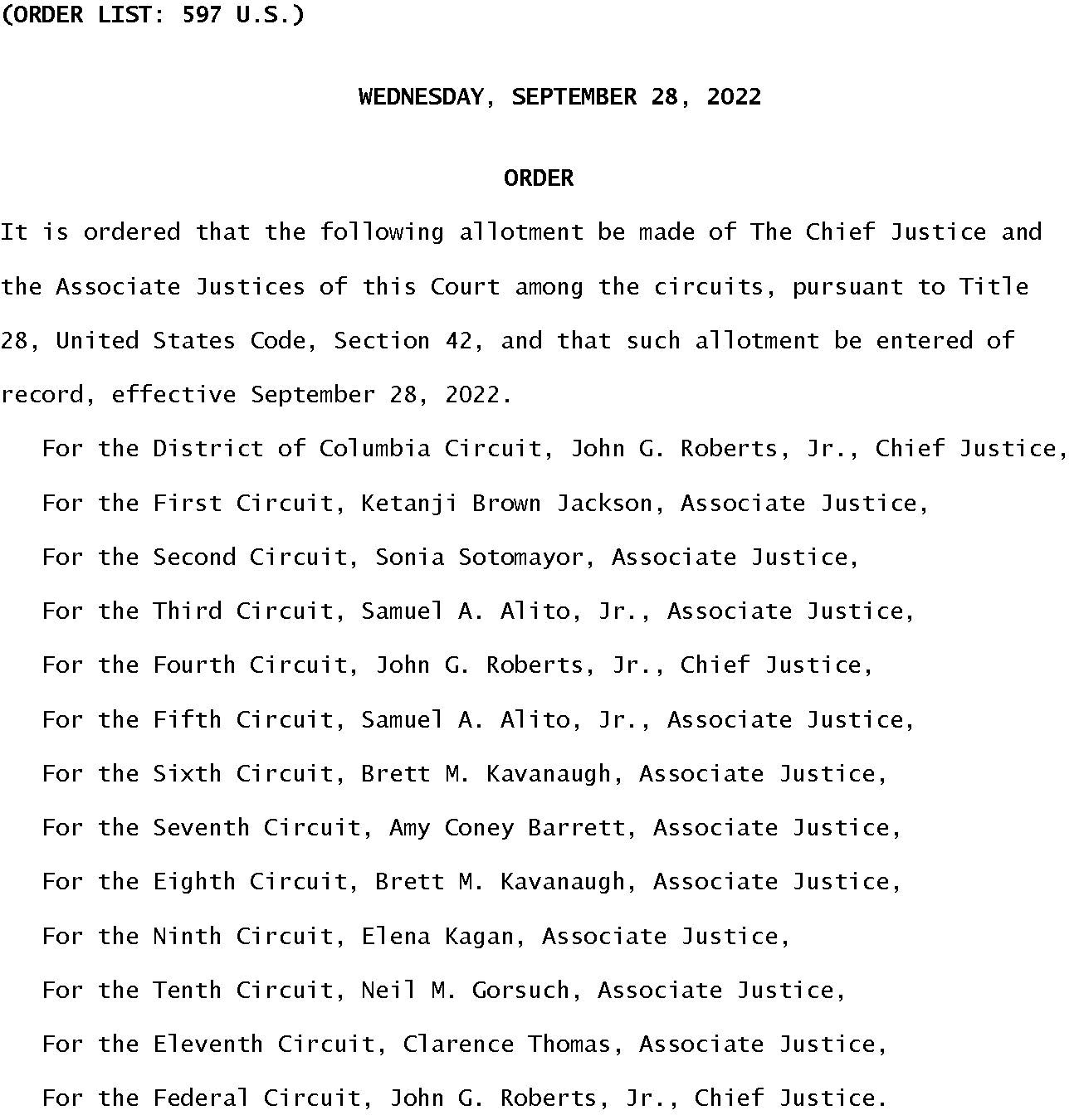

The overwhelming majority of applications, and virtually every application in the first and third categories described above, is filed with, and decided by, the “Circuit Justice”—the one of the nine justices with geographic responsibility for all cases coming from a particular part of the country. (Although the “allotment of justices” depicted below refers to specific federal circuit courts of appeals, the Circuit Justice is also responsible for applications relating to decisions by state courts in that same geographic area—e.g., Justice Sotomayor would handle cases from the Connecticut Supreme Court.) Logistically, the application is filed with the Clerk of the Court, who then directs it to the appropriate justice. But the tradition is for the application to be addressed to the Circuit Justice, as such. (And applications relating to the Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces, by rule, are directed to the Chief Justice.)

By both statute and rule, the Circuit Justice has the power to grant or deny virtually all of the relief a party might seek through an application—including emergency relief. Indeed, until 1980, the norm was that just about all applications, including those seeking emergency relief, would be resolved by the Circuit Justice acting alone. Circuit Justices are empowered to hold (“in-chambers”) oral arguments on an application (although there hasn’t been such an argument since 1980). And their disposition of the application can come through a signed (“in-chambers”) opinion, although those are also quite rare; there’s been exactly one since 2014.

Scenario 1: The Circuit Justice Acts Summarily

Let’s start with the non-contentious applications, i.e., procedural requests or patently meritless applications for emergency relief. These applications (which, again, typically represent more than 90% of the total number of applications the Court receives) are usually handled by the Circuit Justice alone. He or she will grant or deny the application (for procedural requests) or summarily deny the application (for patently meritless emergency applications) in a brief, formulaic order. And such an order is not published by the Court as such; in any of these contexts, the Circuit Justice’s action appears only as a notation on the docket page for the specific case (and is transmitted to the parties both electronically and by mail).

Technically, the Supreme Court’s rules allow the applicant, once the Circuit Justice has denied their application, to re-submit the application to any of the other justices. (As I’ve explained in a previous issue, the rule is a pre-1980 relic—designed for a time when the full Court was formally adjourned for several months each year, such that a second justice was an emergency backstop in lieu of the full Court.) But today, every time this happens, the application is referred to the full Court and denied as a matter of course. What that tells us, as relevant to this post, is that the justices tend not to make mistakes when they act summarily—and so there’s some set of norms (and some internal process) by which they’re separating the applications they can handle by themselves from those that require and receive more process, which I try to unpack below the fold.

For those who are not paid subscribers, we’ll be back on Monday (if not sooner) with our regular coverage of the Court. For those who are, please read on.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to One First to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.