Bonus 136: Nationwide Injunctions vs. Nationwide Class Actions

If those who oppose non-plaintiff-specific relief are doing so on principle and not just politics, they should support more robust nationwide class action suits against the federal government.

Welcome back to the weekly bonus content for “One First.” Although Monday’s regular newsletter will remain free for as long as I’m able to do this, I put much of the bonus content behind a paywall as an added incentive for those who are willing and able to support the work that goes into putting this newsletter together every week. I’m grateful to those of you who are already paid subscribers, and I hope that those of you who aren’t will consider a paid subscription if and when your circumstances permit.

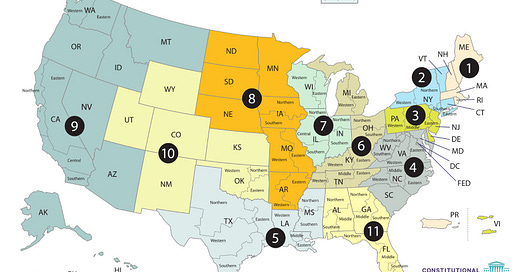

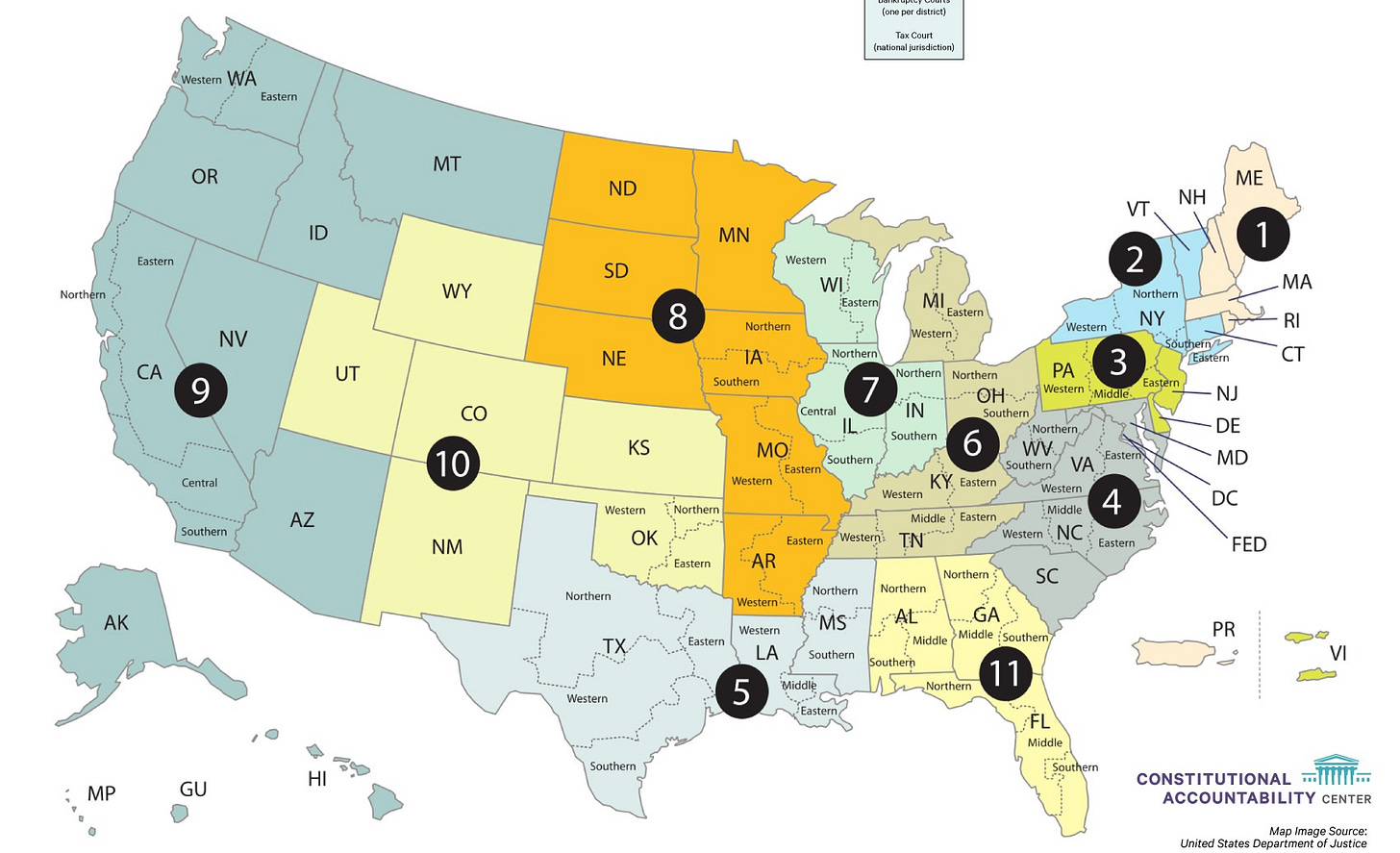

I wanted to use today’s bonus issue to reflect upon a pair of Supreme Court-related congressional hearings from earlier this week: Tuesday’s hearing before the full House Judiciary Committee, and yesterday’s hearing before the full Senate Judiciary Committee, both of which were ostensibly about the need to limit “nationwide” injunctions in reaction to the rash of such rulings against Trump administration policies (the distribution of which was the focus of Monday’s newsletter). [A “nationwide” injunction is one that bars the defendant from taking the challenged action in general, and not just against the named plaintiffs.]

I was the minority witness at the latter hearing, and used my testimony to focus on three basic claims: (1) that this seems like a uniquely poor moment for Congress to be focused on limiting the ability of the federal courts to rein in executive branch lawlessness; (2) that abuses of nationwide injunctions in recent years have been less about the scope of the relief district courts have provided than they have been about abuses by parties and courts of other procedural doctrines (especially standing and venue); and that any reforms should therefore be based on a holistic assessment of how to maximize accountability in both directions—so that courts are properly checked, but so that they don’t lose their ability to meaningfully check the other branches along the way. As I suggested, if Republicans’ current outrage is really about neutral procedural rules, and not just an attempt to insulate much of President Trump’s behavior from judicial review, one solution is simple: have any reforms go into effect on January 20, 2029.

But there’s another point that came up briefly during the Senate hearing that I wanted to expand upon here: Our judicial system already has a procedure for ensuring that every affected party can benefit from a single court order blocking an unlawful federal policy: the nationwide class action. And as I suggested in my testimony, it doesn’t strike me as entirely coincidental that the rise in nationwide injunctions over the past decade came right on the heels of a series of Supreme Court decisions that made it much harder for courts to certify nationwide classes of plaintiffs.

Nationwide class actions, in other words, should be playing a much more central role in debates over nationwide injunctions. Their long existence underscores that it’s generally permissible for a “single district judge” to enter relief that effectively blocks a state or federal policy on a universal basis. And their (problematic) neutering by the Supreme Court underscores that those who believe courts should be able to hold the executive meaningfully accountable, but who don’t love nationwide injunctions, have an easy fix: Reinvigorate the nationwide (or, for state policies, statewide) class action—something Congress unquestionably has the power to do.

In short, an easy way for Republicans to show that their hostility to nationwide injunctions is really about principle, and not just short-term partisan political gain, would be if any bill limiting nationwide injunctions simultaneously made it easier for courts to certify nationwide classes—at least when the plaintiffs are challenging federal policies (ditto, certifying statewide classes for challenges to state policies). Otherwise, opposing nationwide injunctions while refusing to consider an obvious, well-settled, and less controversial alternative leaves at least the appearance that the effort to limit nationwide injunctions is little more than an attempt to insulate this President, at this moment, from most judicial review.

For those who are not paid subscribers, we’ll be back on Monday (if not sooner) with our regular coverage of the Court. For those who are, please read on.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to One First to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.