Bonus 117: Opinions vs. Judgments

An obscure 1949 decision about the District of Columbia helps to illustrate the elusive but sometimes critical distinction between what majorities *say* in a case and what the majority's judgment *is*

Welcome back to the weekly bonus content for “One First.” Although Monday’s regular newsletter will remain free for as long as I’m able to do this, much of the bonus content is behind a paywall as an added incentive for those who are willing and able to support the work that goes into putting this newsletter together every week. I’m grateful to those of you who are already paid subscribers, and hope that those of you who aren’t will consider a paid subscription if and when your circumstances permit:

For obvious reasons, the newsletter has been focused on news-driven posts over the last few weeks—a phenomenon that is likely only to continue from next Monday onwards. With that in mind, I thought I’d use today’s bonus post for something a little lighter and less present-ist: The strange but true math behind the Supreme Court’s 1949 decision in National Mutual Insurance Co. v. Tidewater Transfer Co.

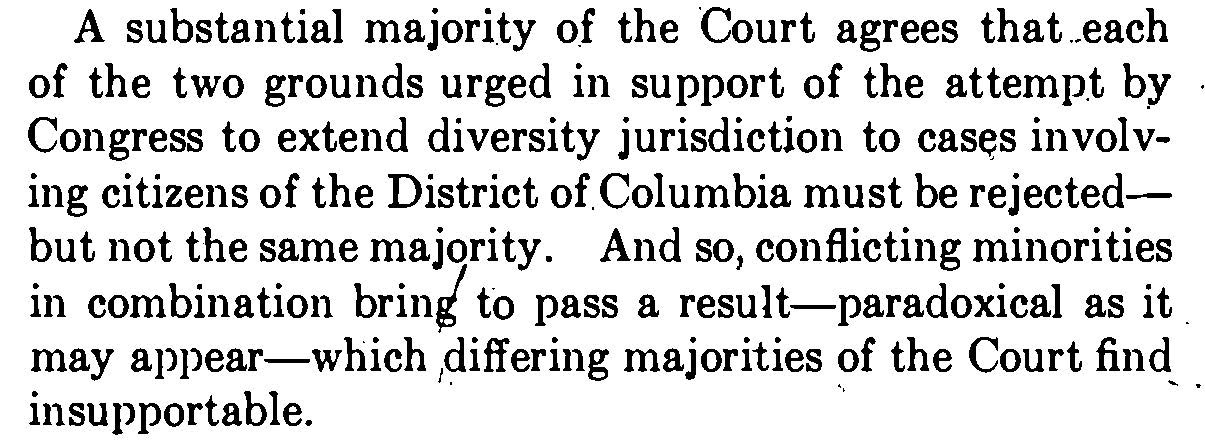

Chances are, you’ve never heard of the Tidewater Transfer ruling. Its bottom-line is easy enough to describe: For purposes of federal court “diversity” jurisdiction (under which federal courts can hear suits by citizens of one state against citizens of other states even when their claims arise only under state law), citizens of the District of Columbia count as citizens of a state. What’s striking (and educational) about that bottom line is the lack of a rationale to support it. One argument (that the District of Columbia should be treated as a state for purposes of Article III of the Constitution) was rejected by a majority of the Court. The other argument (that Congress could confer diversity jurisdiction beyond the scope of Article III) was also rejected by a majority of the Court. But because three justices supported the latter theory and two other justices supported the former theory, those two minority opinions combined to produce a 5-4 majority judgment.

As Justice Frankfurter put it in his dissent:

It’s an object lesson in the difference between the Supreme Court’s opinions and its judgments—and one I expand upon below the fold. For those who are not paid subscribers, the next free installment of the newsletter will drop on Monday morning. For those who are, please read on.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to One First to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.