Bonus 112: Birthright Citizenship, "Invasions," and the Supreme Court

President Trump has vowed to go after birthright citizenship on his first day in office. He's going to lose, but in a way that may well provide cover for other controversial immigration measures

Welcome back to the weekly bonus content for “One First.” Although Monday’s regular newsletter will remain free for as long as I’m able to do this, much of the bonus content is behind a paywall as an added incentive for those who are willing and able to support the work that goes into putting this newsletter together every week. I’m grateful to those of you who are already paid subscribers, and hope that those of you who aren’t will consider a paid subscription if and when your circumstances permit:

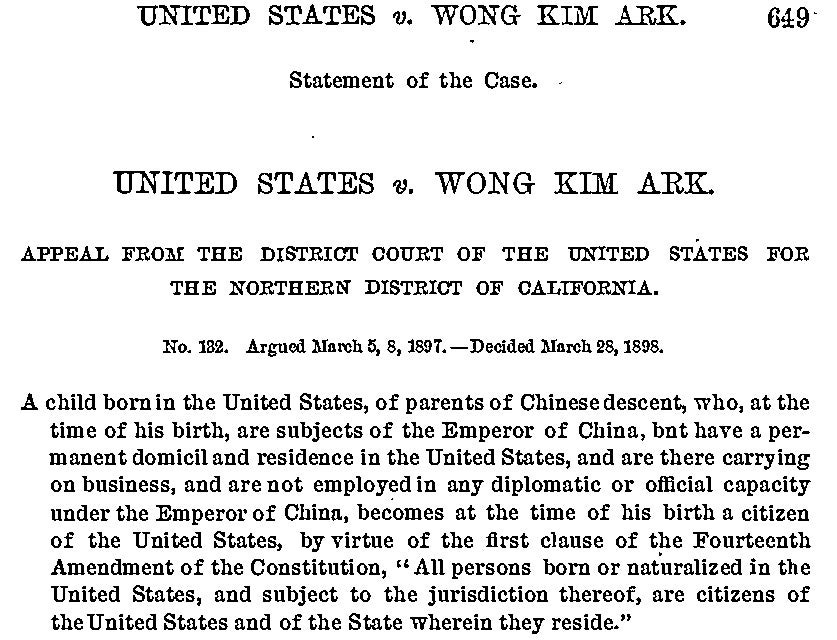

President-Elect Trump has continued to reiterate his pledge to “do away with” birthright citizenship as soon as he comes to office next January. I thought it might be helpful to use today’s bonus issue to talk about why there’s virtually no way in which, legally, the President could restrict birthright citizenship by executive order—because (1) there’s a federal statute that protects it; (2) even if there wasn’t, the Supreme Court expressly interpreted the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to confer birthright citizenship in its 1898 ruling in United States v. Wong Kim Ark (a ruling that I’m confident a majority of this Court would follow); and (3) the only not-completely-frivolous ground on which to try to distinguish Wong Kim Ark is … effectively frivolous.

To make a long story short(er), I have no doubt that Trump will try to do something that looks like a restriction of birthright citizenship. And whatever he attempts might even meet with at least some initial success (although it would be harder to implement than the travel ban—where there was an immediate opportunity to deny entry to folks arriving into the United States on international flights). But for as cynical as many have become about constitutional interpretation in this day and age, there are compelling reasons to believe that birthright citizenship is not going anywhere, anytime soon. The larger issue is the possibility that headlines about Trump being rebuffed on birthright citizenship may obfuscate more effective, but perhaps no-less-legally-dubious shifts in immigration policy in the new administration.

For those who are not paid subscribers, the next free installment of the newsletter will drop on Monday morning. For those who are, please read on.

Let’s start at the beginning. “Birthright citizenship” is the idea that individuals born on U.S. soil are automatically entitled to U.S. citizenship, with almost no regard for the particular circumstances that brought them (and their biological parents) here. The Constitution recognizes the principle of birthright citizenship through the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment—the very first sentence of that provision:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.

Ratified shortly after the end of the Civil War, the Citizenship Clause was meant, unambiguously, to overrule the Supreme Court’s 1857 decision in the Dred Scott case, in which the court had infamously ruled that slaves and their descendants were not, and could not be, citizens of the United States. By its plain terms, those both born in the United States and subject to its jurisdiction are citizens, full stop.

Recently, some commentators have seized upon the “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” language to argue that, in fact, the Citizenship Clause only applies to those who have lawful immigration status—and so excludes children born on U.S. soil to undocumented immigrants. As Fifth Circuit Judge James Ho (appointed by Trump) wrote in a 2006 essay, this argument cannot be reconciled with either the text or the original understanding of the Citizenship Clause, which confirms that it “plainly guarantees birthright citizenship to the U.S.-born children of all persons subject to U.S. sovereign authority and laws.” As we’ll see below, the Supreme Court has been clear for … a very long time … that only three very specific categories of people “in” the United States are nevertheless not “subject to U.S. sovereign authority and laws,” and undocumented immigrants aren’t one of them. (More on Judge Ho’s … transparent … effort to distance himself from his own essay in a moment.)

Indeed, it turns out that there are three different reasons why it would be virtually impossible for a President to get rid of, or even limit, birthright citizenship solely by executive order. And it’s worth walking through each of them, one at a time.

Obstacle #1: Existing Federal Statutes

First, much of the current discourse surrounding birthright citizenship and the Fourteenth Amendment has neglected to note that, before we ever get to the Constitution, there’s a federal statute that guarantees birthright citizenship. In listing those who are “nationals and citizens of the United States at birth,” 8 U.S.C. § 1401’s first example is “a person born in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” Thus, Congress has provided a statutory right to citizenship that courts have historically interpreted to provide the very birthright citizenship that Trump wants to reinterpret the Constitution to exclude.

The existence of the statute matters for (at least) three reasons: First, even statutes that use the same language as the Constitution are often interpreted to mean different things—reflecting the reality that different bodies adopted that text at different times, and perhaps for different reasons. (A nerdy example is the chasm that separates the scope of “arising under” subject-matter jurisdiction under Article III and the similarly-worded-but-much-narrower federal question statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1331.) Here, Congress provided birthright citizenship even before the Fourteenth Amendment required it—in section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866. So there is at least an argument that they’re not automatically covering the same cases. Second, courts generally (and the Supreme Court, specifically) apply an even stronger form of stare decisis to statutory interpretations. Thus, it would be even harder to persuade courts to abandon a long-settled understanding of § 1401(a) than it would be to persuade the Supreme Court to re-interpret the Citizenship Clause. And third, the statute provides a way to resolve legal challenges to any action Trump might take without having to revisit the scope of the Citizenship Clause. Thus, courts could invalidate any effort to limit citizenship by executive order solely on the ground that it contravenes federal statutory law—and save for another day whether Congress could relax the constitutional rule.

Obstacle #2: Wong Kim Ark (and Others…)

The statute doesn’t settle matters, of course. But I think there’s a pretty compelling argument that the Supreme Court already has—and not just in Wong Kim Ark.

But let’s start with that 1898 case (about which professors Carol Nackenoff and Julie Novkov recently wrote a wonderful book). There, after exhaustively retracing the historical understanding of citizenship in pre-revolutionary England, the Supreme Court explained that the “real object” of the “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” language was to exclude from its coverage exactly three classes of individuals: children of Native American tribes born on reservations “standing in a peculiar relation to the National Government;” “children born of alien enemies in hostile occupation” during wartime (we’re going to come back to this one); and “children of diplomatic representatives of a foreign State.” That was it. Otherwise, anyone born on U.S. soil was entitled to birthright citizenship regardless of how they got there or the immigration status of their parents—including Wong Kim Ark, who had been born in San Francisco in the 1870s to Chinese immigrant parents.

The Wong Kim Ark case is not a dusty, antiquated relic. In 1982, the Supreme Court not only reaffirmed its holding, but made express what it had held implicitly—that the Citizenship Clause therefore applies to children of undocumented immigrants, specifically. As the Court explained in Plyler v. Doe, “no plausible distinction with respect to Fourteenth Amendment ‘jurisdiction’ can be drawn between resident aliens whose entry into the United States was lawful, and resident aliens whose entry was unlawful.” And three years later, the court was even more explicit. Referring to the married, undocumented immigrants at issue in that case, the court noted that they “had given birth to a child, who, born in the United States, was a citizen of the country.”

In other words, Wong Kim Ark can’t be pigeonholed as a 126-year-old decision that didn’t speak to the matter at hand; it specifically identified the only exceptions to the Citizenship Clause; and the Supreme Court has since made clear, twice, that children of undocumented immigrants don’t fall within them simply because their parents are out of lawful immigration status. Thus, as the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel concluded in 1995, the Supreme Court has clearly and specifically addressed the issue—and so there is no reasonable way to argue that the Supreme Court’s consistent interpretation of this constitutional text could be overridden by an Executive Order (or, arguably, even a repeal of § 1401(a)). Put more succinctly, as Judge Ho concluded in his 2006 essay, “a constitutional amendment is ... the only way to restrict birthright citizenship.”

Obstacle #3: The Cynical Weakness of the “Invasion” Argument

Enter (or, re-enter, Judge Ho): In a recent “interview” with a friendly blogger that some might construe as an audition for a promotion, Ho has “clarified” that he thinks there’s an important exception that his 2006 essay somehow neglected to mention—and that (he insinuates) Wong Kim Ark didn’t consider: The argument is that, just as children born to enemy soldiers while they are invading the United States obviously aren’t covered by the Citizenship Clause, so too, children of undocumented immigrants who have likewise “invaded” the United States:

birthright citizenship obviously doesn't apply in case of war or invasion. No one to my knowledge has ever argued that the children of invading aliens are entitled to birthright citizenship. And I can't imagine what the legal argument for that would be. It's like the debate over unlawful combatants after 9/11. Everyone agrees that birthright citizenship doesn't apply to the children of lawful combatants. And it's hard to see anyone arguing that unlawful combatants should be treated more favorably than lawful combatants.

First, and just to be clear, Ho’s argument is already reading the historical exception to birthright citizenship that Wong Kim Ark identified far more capaciously than the Court actually said it was. There, in reviewing the common law practice in pre-revolutionary (and post-revolutionary) England, Justice Gray’s majority opinion referred specifically to children born to “an alien enemy in hostile occupation of the place where the child was born.” That’s not just a claim about “invasion” (as Judge Ho suggested); it’s a specific claim about “hostile occupation”—that a foreign sovereign is an occupying power of the place where (and at the time when) the child at issue is born. (E.g., when the British controlled parts of the country during the War of 1812.)

Second, once properly distinguished from the argument that individual undocumented immigrants are “invaders,” it becomes clear why, no matter what one thinks about the “invasion” question, the historical exception still isn’t satisfied. After all, for all of the linguistic debate we can have about what it means for a citizen of one country to “invade” another, “hostile occupation” means something far more specific—and is, as Wong Kim Ark recognized, a reference to specific conditions that obtained when a foreign army was in control of another sovereign’s territory. Consider, in this regard, the handful of Nazi soldiers who were captured and/or arrested on U.S. soil during World War II (like the Nazi saboteurs). They were unquestionably “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States; indeed, that was a critical part of the legal basis for prosecuting them. We had (and have) no comparable authority to prosecute German diplomats.

Third, even if we’re going to collapse the distinction between what Wong Kim Ark (and historical practice) actually said and a more amorphous understanding of “invasion,” as I’ve written before, there is no serious argument that undocumented immigrants, as such, are part of an “invasion” for purposes of the Constitution. Is overstaying a visa “invading” the United States? Is falsifying an application for lawful immigration status “invading” the United States? Indeed, can a person not advancing the mission of a country or other foreign power ever “invade” another country? The answer to all of these questions is, quite obviously, “no.” And the Founders, who came of age at a time in which we had far fewer restrictions on immigration, would never have thought otherwise.

The upshot of all of this is that, for President Trump to be able to take any real bite out of birthright citizenship, he’d have to persuade the Supreme Court to read a statute to mean something other than what it’s been understood to mean for 158 years; to ignore what the Court’s predecessors said in Wong Kim Ark about the breadth of birthright citizenship; to overrule the two more-recent cases specifically recognizing children of undocumented immigrants as citizens; to collapse the distinction in Wong Kim Ark (and historical practice) between “hostile occupation” and “invasion”; and, even then, to persuade five justices that undocumented immigrants, regardless of their country of nationality, are “invading” the United States for constitutional purposes—and are somehow not “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” while they are here (which would pose its own problems for trying to enforce our immigration laws against them).

I understand that we live in an age of cynicism about the courts, but I feel pretty confident that this just isn’t going to happen. Maybe there are two justices on the current Court who will find this reasoning alluring; maybe there are even three. But there are some lines that not even this Court would be willing to cross. And I respectfully submit that Wong Kim Ark’s understanding of birthright citizenship is one of them.

***

That’s not to say that there won’t be mischief along the way—from the Trump administration’s efforts to make a bigger deal out of whatever Trump tries than it actually is; and perhaps in the form of emergency relief that the Court might be willing to grant while it considers the merits. But unlike in the travel ban cases, the consequences of trying to restrict birthright citizenship should not be quite as immediately felt (changing the stakes and the optics of emergency relief). And the broader constitutional principle at stake is one that I just can’t see four justices endorsing—let alone five.

Of course, all of this assumes that scaling back birthright citizenship would be the principal focus of a second Trump administration’s immigration policy. Given just how much of a stretch the legal arguments on the citizenship front are, though, we ought to consider the possibility that, in fact, the hullabaloo surrounding birthright citizenship ends up—deliberately or not—distracting from more effective, and more legally defensible (if not necessarily legal) shifts in immigration policy that come along at the same time.

One of the challenges of the second Trump administration is going to be the extent to which we’ll all be drinking from a firehose on these topics. Birthright citizenship will obviously get far more attention than technical changes in things like deportation priorities and family separations. But relative to its chances of succeeding in court and the harm the policy will impose on the ground, that may not necessarily be deserved.

We’ll be back Monday with a regular issue of the newsletter—focusing on the rather stunning disappearance from the Court’s docket of direct appeals from state criminal convictions.

Until then, thanks again for continuing to support “One First.” I hope you have a great weekend.

Another exceptional article. Thank you.

Very informative article