Bonus 111: Three Ways to Improve Supreme Court Statistics

Both the official and unofficial compilers of annual Supreme Court caseload statistics (or, at least, those relying upon their data) could benefit from some modest methodological changes

Welcome back to the weekly bonus content for “One First.” Although Monday’s regular newsletter will remain free for as long as I’m able to do this, much of the bonus content is behind a paywall as an added incentive for those who are willing and able to support the work that goes into putting this newsletter together every week. I’m grateful to those of you who are already paid subscribers, and hope that those of you who aren’t will consider a paid subscription if and when your circumstances permit:

I was motivated to write about today’s topic by the annual mid-November publication of the Harvard Law Review’s Supreme Court issue. The issue is perhaps best known for the “Foreword”—in which a scholar is invited to provide a broader, thematic assessment of the Court’s most recent term (an invitation that has become one of the highest honors at least among public law scholars). This year’s lead piece, by Penn law professor Karen Tani, is an exemplary entry in the field.

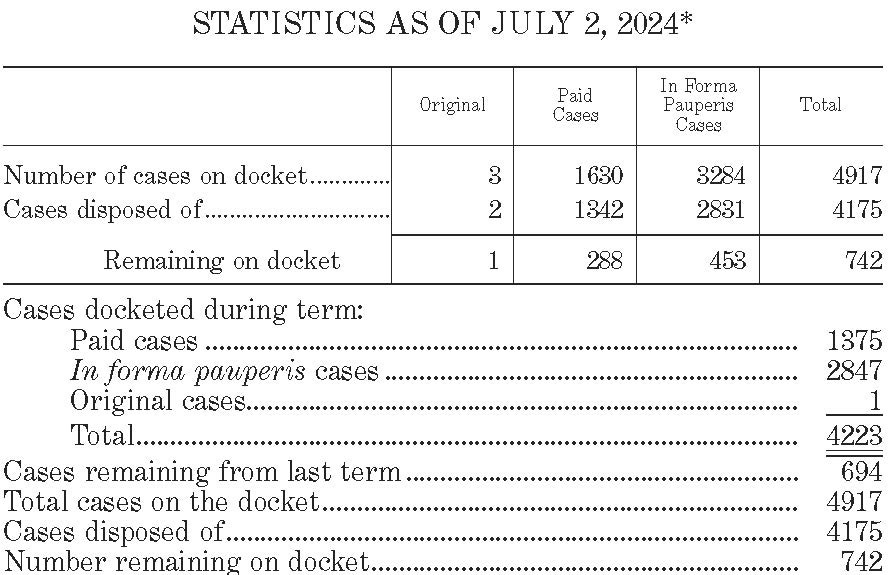

But because I’m a huge nerd, I also spend a lot of time with “The Statistics”— which the Review has published, in some shape or form, every year since 1949. Especially with the demise of SCOTUSblog’s annual “Stat Pack,” the “Statistics” feature has become the most comprehensive place to find annual, if unofficial, numerical compilations of the Supreme Court’s output. Indeed, the Review’s statistics are far more comprehensive than the relatively modest annual data that the Supreme Court itself publishes at the beginning of its Journal.

But hearkening back to the annual pieces that then-Professor Felix Frankfurter used to publish on “the business of the Supreme Court,” which combined statistics with a more narrative view of the Court’s work, I wanted to flag three different methodological shortcomings in these datasets—and how and why addressing those defects would be useful to anyone trying to better understand the overall workload of the Court. As I explain below the fold, (1) both the Review and the Supreme Court are counting the wrong time periods; (2) both are also creating a numerator/denominator mismatch; and (3) the Supreme Court is maintaining, but not publishing, far more useful data about the shape of its docket. These may seem like relatively modest things to flag when it comes to keeping track of the Supreme Court, but the harder that it is to study the Court, the harder it is to get a sense of what’s different about the Court’s behavior today in comparison to its predecessors—and to assess claims like the one Justice Gorsuch made over the summer, that the reason the Court’s docket is shrinking is because it’s receiving fewer appeals.

For those who are not paid subscribers, the next free installment of the newsletter will drop on Monday morning. For those who are, please read on.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to One First to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.