Bonus 1: Three Crazy Supreme Court Decisions You've (Probably) Never Heard Of

In this week's (inaugural) bonus content, Steve recaps three of his favorite bizarre-but-obscure (or obscure-but-bizarre?) Supreme Court decisions

Welcome to your inaugural dose of bonus content here at “One First”!

In addition to the regular (free) Monday newsletter, every Thursday, paid subscribers to “One First” will receive access to fun (I hope) bonus content—featuring more of a personal spin on me and my Supreme Court-related work, along with more opportunities for us to interact and for me to answer your questions. (Okay, and maybe share the occasional pictures of Roxy.)

If you’re not a paid subscriber, fear not; you didn’t receive this in error. To help give everyone a sense of what to expect from the bonus content, the first two bonus posts (today’s and next week’s) will be free and available to all. Starting after Thanksgiving, the main weekly Monday post will remain free to all, but the bonus content will be available to paid subscribers only. (And if you’re already not a free or paid subscriber, now’s a good time to start!)

For this week’s bonus content, I thought I’d introduce three of my favorite strange-but-true Supreme Court decisions. None of these are staples of most law school classes (or any list of the Supreme Court’s most important decisions), but each of them (1) has an element of the bizarre; and (2) continues to have significant effects today (and I also just find them compelling in different ways): Luther v. Borden (1849); In re Neagle (1890); and Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League (1922).

The bonus content won’t always be quite this … dense substantive; I leave to you whether that’s a feature or a bug. But as you ponder, cozy up with your favorite beverage (Gold Peak Zero Sugar Sweet Tea for me), and let’s dive in to some truly wacky cases you (probably) haven’t heard of or, even if you have, dwelt upon.

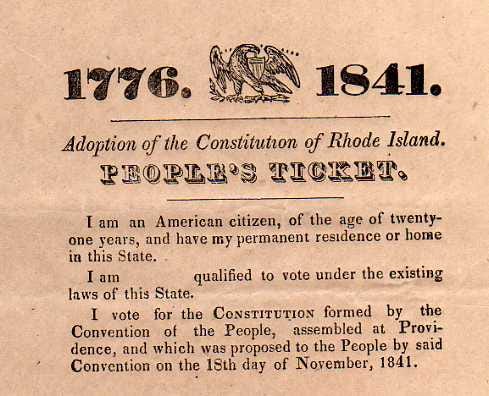

Luther: Which is the Government of Rhode Island?

Rhode Island (and Providence Plantations) was the only one of the original 13 states that didn’t write a new constitution around the time of the American Revolution. Instead, into the 1800s, it was still governed by the 1663 Royal Charter, which, among other things, did not exactly apportion the state legislature … fairly (only wealthy male landowners could vote). Refusal on the part of the “Charterist” government to pursue reforms as the underrepresented urban population grew led to growing discontent, until a group led by Thomas Wilson Dorr wrote their own (“People’s”) constitution and purported to adopt it in November 1841.

Both the Dorrites and the Charterists held elections in 1842 (see the “People’s Ticket,” above), leading to Dorr’s Rebellion (or “the Dorr War”)—in which neither camp was willing to accept the other’s lawful authority, so there were, at the same time, two competing groups calling themselves the duly elected Rhode Island state government.

Luther v. Borden started when Luther Borden, an official under the Charterist government, sought to arrest a Dorrite supporter named (you can’t make this up) Martin Luther. Borden entered Luther’s home without permission (and allegedly damaged his property). When Luther sued Borden for trespassing on his property, Borden’s defense was that he had lawful authority because he was a representative of the Charterist government. Thus, Borden’s defense turned on which group was the lawful government of Rhode Island—the Dorrites (in which case, Luther should win) or the Charterists (in which case, Borden should win).

Luther’s response, and his principal argument that the Dorrites were the proper government, was that the Charter government was not “Republican,” and thus was in violation of the “Republican Form of Government” Clause of the Constitution, Article IV, Section 4:

The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government, and shall protect each of them against Invasion; and on Application of the Legislature, or of the Executive (when the Legislature cannot be convened) against domestic Violence.

Rather than expressly choose between the Dorrites and the Charterists, Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney (he of Dred Scott infame) punted, holding that the “Republican Form of Government” Clause is not subject to judicial enforcement. His logic (if you can call it that) was that Congress decides which is the duly elected government of a state when it chooses to seat representatives, and it wasn’t for the courts to second-guess Congress’s decision in early 1843 to seat the Charterists. Luther thus became an early example of one class of cases under the “political question doctrine,” in which, at least according to the Supreme Court, the Constitution itself has textually committed the power to render a final decision to an entity other than the courts.

Taney’s reasoning left more than a little to be desired. Among other things, the text of the Republican Form of Government Clause says nothing about Congress, and instead contemplates a significant role for the President. Indeed, both the Charterists and the Dorrites had sought assistance from “His Accidency”—President John Tyler, who declined to send troops to support either group (but clearly had both the statutory and constitutional authority to do so). And it’s hard to imagine that, if Congress seated one faction and the President sent troops to support the other one, the courts would still feel impelled to sit things out rather than resolve the impasse.

Whatever its merits, though, Luther still stands today for the proposition that the Republican Form of Government Clause can’t be enforced by the courts, which has had (and continues to have) massive implications in limiting the ability of federal courts to police, among other things, partisan gerrymandering and other disputes over the representativeness (or lack thereof) of state legislatures. (Rhode Island soon came to its senses and adopted a new constitution.)

But it’s also pretty wild that, in 1849, the Supreme Court was faced with a genuine dispute in which the answer to a routine trespass case turned on which government claiming to be “Rhode Island” was in fact the legitimate one—and the Justices said “¯\_(ツ)_/¯”.

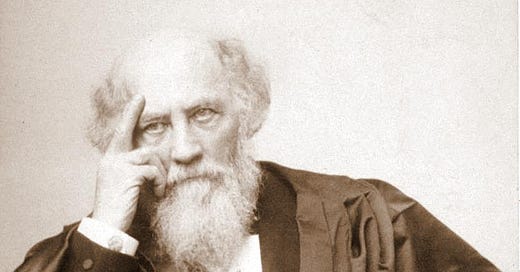

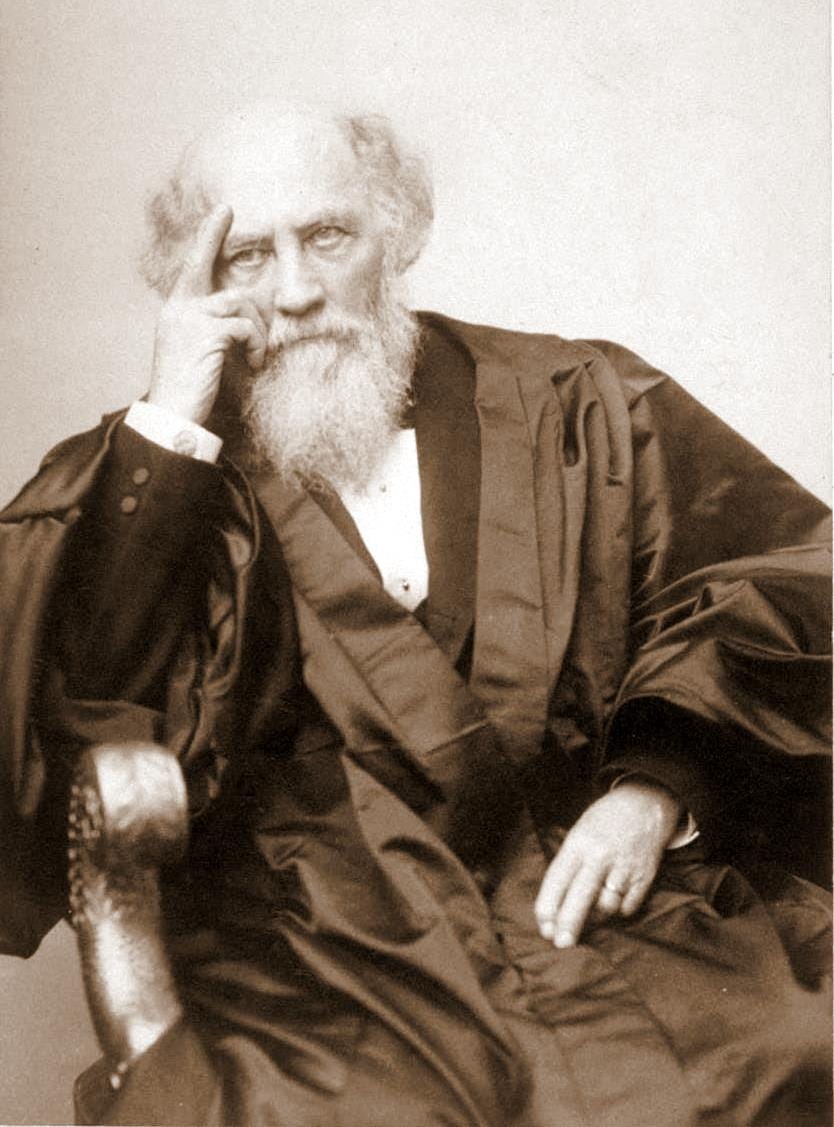

Neagle: Protecting Justice Field, Over Two Dissents

Justice Stephen Field was a character. One of the many Americans who flocked to California during the late-1840s Gold Rush, Field quickly became one of the leading lawyers in the state, winning election to the California Supreme Court in 1857. As a jurist, Field’s reputation was … ornery. One of his critics suggested that those who analyzed his life would find it to be a “series of little-mindedness, meanlinesses, of braggadocio, pusillanimity, and contemptible vanity.” A notorious holder of grudges, one contemporary observed that “when Field hates, he hates for keeps.”

His personal foibles aside, Field was a staunch Unionist. So when Congress added a new (10th) seat to the Supreme Court in 1863 to account for the new California-based federal courts, Field was at the top of a very short list of lawyers suitable for nomination. He ended up serving on the Court for 34 years, deliberately staying on the bench even after his faculties declined because he wanted to break Chief Justice John Marshall’s then-record for longest-serving Justice (he’d eventually best Marshall by 33 days, only to be overtaken by Justice William Douglas in 1973). And Field is perhaps best remembered for his commitment to free enterprise unchecked by government regulation—one of the most ardent supporters of property rights in the Court’s history.

But Field was also the key figure in a legal dispute that reached the Supreme Court in 1890. While “riding circuit” (sitting as a circuit judge) in California, Field had presided over a contentious case involving a claim by Sarah Hill, represented by her then-husband David Terry (who had once been Field’s colleague on the California Supreme Court), that Hill had previously been married to a silver baron, and was therefore entitled to a share of his estate. (My friend and gifted Supreme Court observer Garrett Epps recounted much of the background for The Atlantic in 2016.) On September 3, 1888, Field ruled against Hill (and Terry), and, although accounts differ on who started it, eventually held both of them in contempt (and sent them to jail) for causing a scene in the courtroom.

Terry vowed revenge. When Field returned to California in June 1889 to once again ride circuit, the Attorney General ordered the local U.S. Attorney to assign Field a bodyguard. The U.S. Attorney assigned David Neagle to accompany Field, in case Terry tried to make good on his threat. Sure enough, when Terry and Field ended up on the same overnight train from Los Angeles to San Francisco on August 14, matters came to a head. Terry tried to attack Field at a railroad stop in Lathrop. According to witnesses, Neagle raised his pistol and shouted “Stop! Stop! I am an officer!” When Terry reached into his pocket, Neagle killed him with two shots.

Field and Neagle were jailed on charges of murder (yes, this is the only time in American history that a sitting Supreme Court Justice has been arrested on felony charges). But although Field was quickly released (apparently via a writ of habeas corpus), Neagle’s case was harder. The issue Neagle’s petition raised was that Congress had never specifically authorized his appointment. So whether he was acting lawfully in defense of Field when he shot and killed Terry turned on whether the U.S. Attorney had the unilateral legal authority to deputize him—whether the Constitution gave the Executive Branch the power to protect key federal officers even if Congress hadn’t provided for it.

The dispute reached the Supreme Court the next year. Writing for the Court, Justice Samuel Miller upheld Neagle’s appointment: “We cannot doubt the power of the president to take measures for the protection of a judge of one of the courts of the United States who, while in the discharge of the duties of his office, is threatened with a personal attack which may probably result in his death.” In that respect, the decision in In re Neagle was an important (if modest) precedent for the Executive Branch’s power to act in some instances without express statutory authorization—although Congress has long-since closed the specific gap for protecting the Justices.

But the best (or craziest) part of the Court’s decision in Neagle (from which Justice Field understandably recused) was that two of his colleagues—Justice L.Q.C. Lamar and Chief Justice Melville Fuller—dissented! In the words of Lamar (who wrote for both of them), “If the act of Terry had resulted in the death of Mr. Justice Field, would the murder of him have been a crime against the United States? … [N]o such statute has yet been pointed out.”

That must’ve been … awkward.

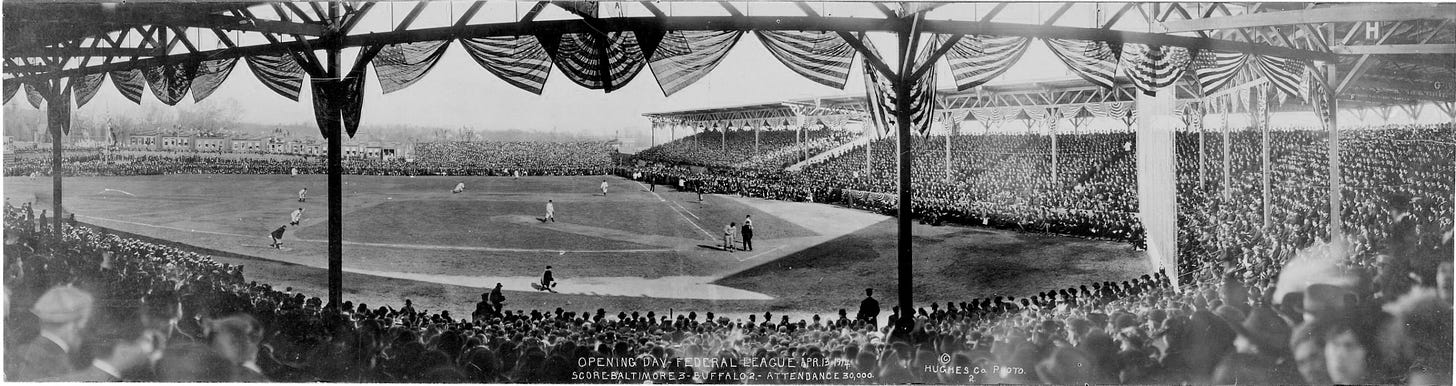

Baseball’s Anachronistic Antitrust Exemption

Luther and Neagle are both significant constitutional law decisions. My third choice isn’t. It’s about federal antitrust law, and, more specifically, why it doesn’t apply to Major League Baseball (baseball’s so-called “antitrust exemption”). And the answer might have made plenty of sense when the Supreme Court handed it down in 1922, but it makes … no sense … today.

For the non-lawyer readers among you, a bit of background might help. In a 1905 decision, Lochner v. New York, the Supreme Court had first recognized circumstances in which state or federal economic regulation would be substantively unconstitutional because it interfered with the “liberty of contract.” (In Lochner itself, this meant striking down New York laws that imposed maximum-hour and minimum-wage requirements on bakers.)

The “Lochner era” was also typified by judicial skepticism of legislative motives, so that when Congress was purporting to regulate interstate commerce, it was up to the Court to decide if interstate commerce was the (permissible) ends of the regulation, or rather the (impermissible) means to reach some end Congress couldn’t reach directly. In 1918, for instance, a 5-4 Court in Hammer v. Dagenhart struck down the Child Labor Act because, even though it prohibited the shipment in interstate commerce of goods produced through child labor, Congress’s “true” goal was regulating child labor, not regulating interstate commerce. In other words, one of the hallmarks of the Lochner era was a narrow understanding of the constitutional scope of “commerce among the states.”

Enter, Major League Baseball. The actual dispute that reached the Supreme Court in 1922 involved the “Federal League,” which had attempted to be a third major league from 1913–15. Because the Federal League was not bound by the “Reserve Clause” (which effectively barred free agency), it offered much higher contracts (and thereby posed a serious threat to the two established leagues). Many of the existing American League and National League owners worked together to destroy the fledgling competitor, including by paying off some of the Federal League’s owners or otherwise interfering with the league’s operations. After the Federal League folded, one of the owners of its Baltimore club (whose 1914 opening day is pictured below) sued, claiming that the American League and National League (and numerous individuals) had violated federal antitrust laws by working together to eliminate a competitor.

Writing for a unanimous Court, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes disagreed, entirely because, in his view, professional baseball was not “commerce among the states,” and therefore not within the purview of the antitrust laws:

The business is giving exhibitions of baseball, which are purely state affairs. It is true that, in order to attain for these exhibitions the great popularity that they have achieved, competitions must be arranged between clubs from different cities and states. But the fact that, in order to give the exhibitions, the Leagues must induce free persons to cross state lines and must arrange and pay for their doing so is not enough to change the character of the business. . . . That which in its consummation is not commerce does not become commerce among the states because the transportation that we have mentioned takes place.

Ignoring the salaries paid to the players or the tickets bought by the fans, the Supreme Court thereby carved professional baseball out of antitrust law because the game itself was an exhibition, and not “commerce among the states.” But the Supreme Court’s understanding of interstate commerce evolved (and expanded) dramatically starting in 1937, such that no other professional sports have been able to benefit from similarly parsimonious statutory interpretations.

The best part of Federal Baseball Club is that, even though the Supreme Court would expressly disagree with its reasoning 50 years later (in Flood v. Kuhn, which is worthy of its own story another time, and not just because of the notoriously poor oral argument performance by former Justice Arthur Goldberg), it refused to overrule the earlier decision. Instead, as then-Tenth Circuit Judge Neil Gorsuch wrote in 2016, “So it is that the baseball rule now applies only to baseball itself, having lost every away game it has played.”

Meanwhile, Congress, which had done nothing to address baseball’s antitrust efforts one way or the other since the Supreme Court’s 1922 ruling, decided to partially limit it and partially enshrine it in October 1998, perhaps because, given the events of that summer, it, too, dug the long ball.

Thanks for checking out this week’s “One First” bonus content. The next regular issue will drop Monday at 8 a.m. ET; and next week’s bonus content, which will have a bit of a personal/Thanksgiving theme, will hit your inboxes at 8 a.m. ET next Thursday.

If you’re already a subscriber, thank you!! And if you’re not yet but you made it this far, what’s one more click?: