98. Why is the Court's Docket Shrinking?

Speaking at the Tenth Circuit Conference, Justice Gorsuch tied the Court's declining output to the declining number of appeals being filed with the justices. There's one *big* flaw with that claim.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current work, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

This week’s “Long Read” was prompted by remarks made by Justice Gorsuch at the Tenth Circuit Conference last week, as reported by Michael Karlik for Colorado Politics. According to Karlik, Gorsuch (the Circuit Justice for the Tenth Circuit) pegged the sharp decline in the number of cases the Court has decided in recent terms to the decline in total number of appeals reaching the justices (Karlik paraphrased Gorsuch as suggesting there are “roughly 40% fewer petitions for review in recent years compared to 10 years prior.”)

Karlik quoted Gorsuch as saying: “Maybe it had something to do with the pandemic and some lower courts were closed for long periods of time and perhaps there's a backlog. Maybe it has something to do with appellate waivers in criminal cases. I don't know,” he said. “Maybe it has something to do with the rise of technology, which makes it so much easier for all of us to know if there's a circuit split.” But, Gorsuch continued, “it does seem to me that if lawyers want our court to take more cases, perhaps they need to file more petitions.”

This last line may well have been tongue-in-cheek (since Gorsuch was speaking to a room full of lawyers). But I was intrigued by Gorsuch’s underlying causal claim—that the Court’s shrinking docket is largely, if not entirely, a function of the Court receiving fewer appeals. There is, undoubtedly, a kernel of truth to it. But a closer look at the data suggests, quite to the contrary, that the Court’s docket has shrunk (dramatically) even as the relevant subset of appeals has remained mostly flat. And there’s lots of anecdotal evidence to support this more nuanced parsing of the data: the issue is not that the Supreme Court Bar is filing fewer (worthy) petitions; the issue is that the justices, for whatever reason, are taking fewer of them.

More on that below. But first, the news.

On the Docket

All things being equal, it was a pretty quiet week at the Court. There was a summary denial (over no public dissents) of an emergency application in a federal criminal case and a routine housekeeping Order List on Friday. The only noteworthy action taken by the full Court was Tuesday’s ruling denying an emergency application from Oklahoma in a dispute over HHS’s withdrawal of certain federal funds in response to Oklahoma’s refusal to publicize a national call-in number for abortion counseling (which is one of the requirements for receiving the federal funding). Oklahoma had asked the Court to turn the funding tap back on notwithstanding its refusal to comply with that requirement; the Court turned away its request—albeit over unexplained public dissents from Justices Thomas, Gorsuch, and Alito.

We’ve still had no action from the Court on the three different pools of emergency applications challenging various EPA rules. The “most” ripe of the sets are the eight applications respecting the new limits on power-plant emissions. Those have been fully briefed for almost three weeks—and some kind of ruling this week would … not be surprising. The government’s response to the seven challenges to the EPA’s new Mercury and Air Toxics Standards isn’t due until this Friday, so we won’t hear anything on those this week. And the Chief Justice finally ordered a response to the two applications challenging the new methane rule—but that isn’t due until next Friday. So it may be another quiet week at the Court—as the justices increasingly turn their attention toward the “Long Conference,” three weeks from today.

The One First “Long Read”:

The Court’s Shrinking … Filings?

I’ve written before about the Court’s shrinking docket—with the current (October 2023) Term checking in as the fifth straight term in which the justices handed down fewer than 60 signed opinions in argued cases—a floor that, with a single exception, they hadn’t previously gone below since … 1864.1 To be sure, the Court’s docket has been shrinking ever since 1988—when Congress removed almost all of its remaining “mandatory” jurisdiction (appeals that the justices must hear). As one data point, in OT1989 (the first term in which the Court’s docket included only cases filed under the post-1988 statutory regime), the Court handed down 129 signed decisions in argued cases—more than twice as many as we’ve seen recently. (The last time the Court hit the century-mark was OT1992.)2

But the drop-off in merits rulings was not linear. By the late 1990s, the average per-term total had stabilized in the mid-70s, where it remained until OT2012 (when the Court handed down 73 rulings in argued cases). That’s why the fall from there is so striking (especially to folks who went to law school between the 1990s and mid-2010s); the Court had appeared to reach a post-1988 equilibrium, only to have something push it toward a new, significantly lower one. Over the last 10 terms, the Court is, on average, deciding 20% fewer cases than it was deciding during the preceding 15. And that number gets closer to a 30% drop-off if we look only at the last five terms. In other words, there’s just no question that the Court’s docket has shrunk—and to a statistically significant degree.

More than just a quantitative claim, discussions of the Court’s declining caseload have pointed to the effective disappearance of a criminal procedure docket; the related-but-somewhat-distinct decline of appeals coming from state courts; and a host of other subject-matter areas where lower-court judges have complained, both publicly and privately, about the justices’ unwillingness to take up cases that their lower-court colleagues believe to be “cert.-worthy.” Nor are these charges coming only from progressive critics of the Court; right-of-center law professors and Republican-appointed circuit judges are front-and-center in at least some of these accounts.

Enter, Justice Gorsuch. In introductory remarks to the Tenth Circuit’s annual Bench and Bar Conference (which do not appear to have been recorded, hence my reliance upon media accounts),3 Gorsuch didn’t dispute that the Court’s caseload has shrunk; he simply chalked it up to the correlative decrease in the total number of appeals being filed. And in a world in which the Court was granting a relatively fixed percentage of all of the appeals that it receives, it should indeed follow that, as the denominator shrinks, the numerator would shrink in kind.

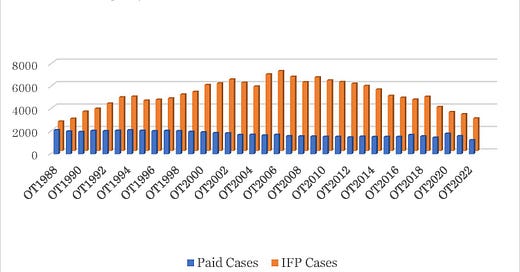

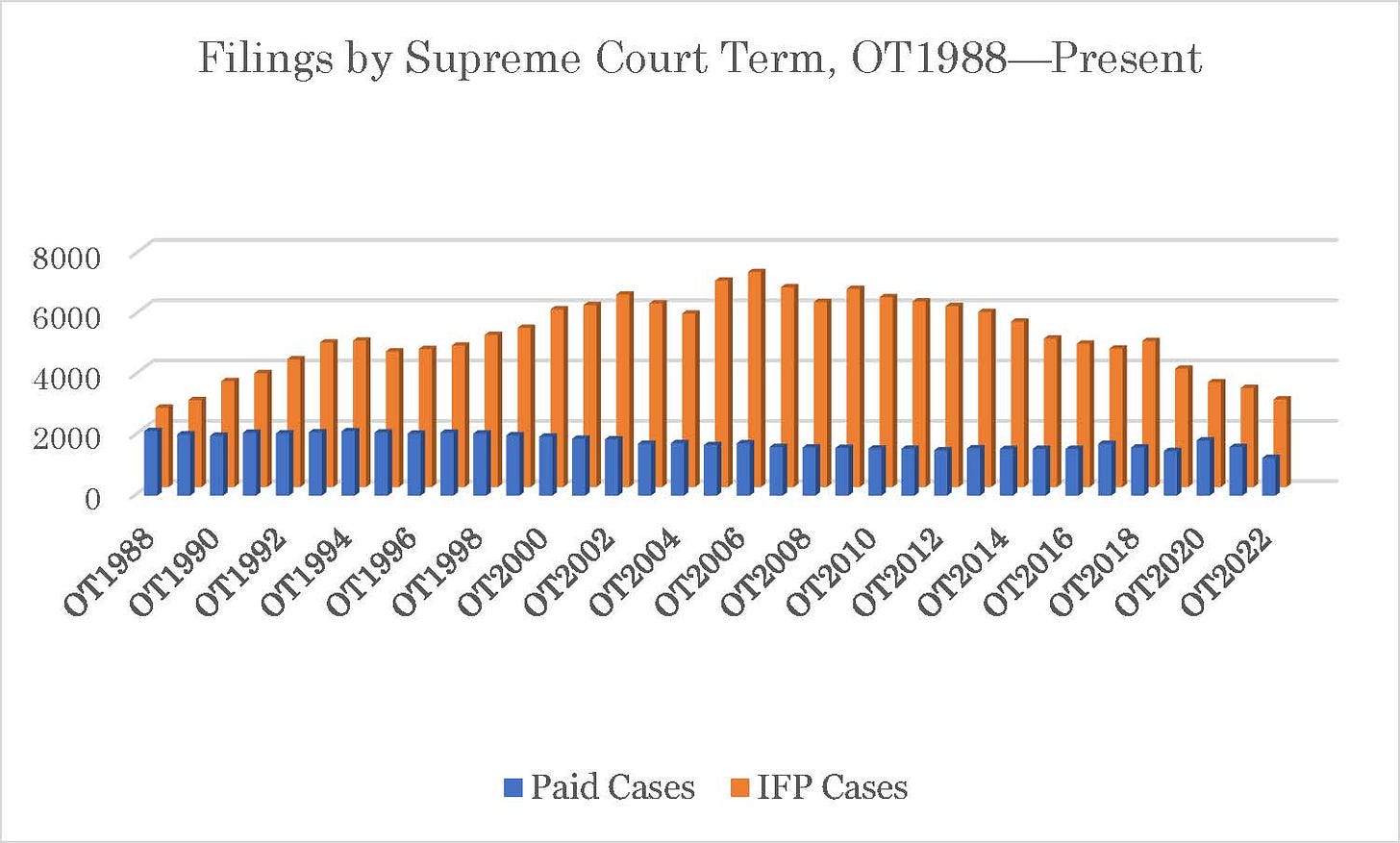

According to the statistics compiled in the Court’s annual Journal (which, though it doesn’t actually measure the correct time period, should be reliable enough for these purposes), as recently as its October 2006 Term (“OT2006”), the Court received 8857 total appeals. That number shrunk all the way to 4159 for OT2022 (the last for which the Court’s data is public), which is a 53.04% drop-off in total appeals. So if one wanted to cherry-pick the data, you could point to those two numbers and be done.

To be sure, OT2006 was an outlier on the high end (likely thanks to surges in post-BIA-streamlining immigration cases and post-Booker criminal cases), and OT2022 was an outlier on the low end (almost certainly thanks to COVID, and fewer total lawsuits being filed in 2020 and 2021). The actual decline probably is closer to the 40% figure cited by Justice Gorsuch (although it would help to know from which term he’s starting). But there’s a huge problem in looking just at the total number of appeals, and it has everything to do with the two different classes of appeals that the Court receives.

The Court’s rules (and even its docket numbers) distinguish between what it calls “paid” appeals (docket numbers starting at yy-1) and those that are filed “in forma pauperis” (docket numbers starting at yy-5001), where the petitioner is not required to pay the filing fee or provide the same type of formatted booklet for his/her briefs.4 The latter category includes cases in which the petitioner is indigent and is either (1) proceeding pro se (i.e., representing themself), or (2) represented by court-appointed counsel. Most of the “IFP” filings end up being from or on behalf of criminal defendants or state or federal prisoners, but there are a meaningful number of “paid” criminal/prisoner cases, as well—and at least a small number of IFP appeals from non-prisoner civil petitioners.5

The distinction between “paid” and “IFP” cases is significant because, both historically and today, the overwhelming majority of the cases the Court chooses to hear come from the paid docket—even though, by percentage, they represent a significant minority of total filings. In OT2012, for example, there were 1504 paid appeals and 6005 IFP appeals—so paid appeals comprised only 20.03% of the Court’s total docket. And yet, of the 93 appeals the Court chose to hear from those 7509 filings, 83 were in paid cases; 10 were IFP. Thus, 20.03% of the Court’s docket accounted for 89.25% of the granted cases. And those numbers have gotten only more one-sided since; during OT2020, paid filings accounted for 34.48% of all appeals, but 95.83% of granted cases.

Some of that shift is because the Court has gotten stingier in granting IFP cases, especially since Justice Kennedy retired. But some of it is also because the total number of IFP filings has dropped off precipitously. In OT2006, there were 7132 IFP filings. In OT2022, there were 2907. And more generally, the average has fallen from roughly 6400 per Term in the 2000s to roughly 4400 per Term over the last decade.

You’ve probably figured out where this is going, but just to tie these threads together, it turns out that the total number of paid filings has remained relatively flat—with only a modest decline since the 2000s. In OT2002, for instance, there were 1869 paid appeals; in OT2020, there were 1830. In OT2008, there were 1596 paid appeals; in OT2021, there were 1612.

Here’s a chart I generated using the Court’s term-over-term data. The X axis is each term dating back to OT1988 (when the Court’s current jurisdictional statutes took effect); the orange bar is the number of IFP filings; the blue bar is the number of paid filings. What this chart (hopefully) drives home is that, although the Court’s total appellate caseload has shrunk significantly in recent years, the paid docket has declined only marginally since the early 2000s. Instead, most of the decline in total appeals has come from the IFP docket—the source of a small minority of the cases that the Court tends to grant:

In other words, the claim that the decline in the number of cases the Court is deciding is because of the decline in the number of cases it is being asked to decide appears to reflect correlation, not causation. The total size of the paid docket, which is the source of almost all of the cases the Court agrees to hear (especially these days), just hasn’t fallen off that much over the past 20 years.

Another way of quantifying this is the “grant rate”—the percentage of appeals that the Court is agreeing to hear. From OT1988 into the early 2000s, the grant rate in paid cases hovered between 4–5% (hitting 5.52% for OT2012). By OT2019, that number had fallen to 3.78%, and 3.77% in OT2020. These may seem like modest declines (and small numbers to begin with), but consider that 3.77% is 68.3% of 5.52%. Put another way, in some of its recent terms, the Court has granted as much as ~31.7% fewer cases from the paid docket than it granted as recently as OT2012. Recall from above that the overall decline in the Court’s decisions is hovering around 30% over the same time period. What this suggests is that the culprit for the Court’s shrinking docket is not a decline in the total number of cases being filed; it’s increasing stinginess on the justices’ part.

Of course, greater stinginess is not inherently a bad thing; the criteria for certiorari are notoriously subjective—and in any event, are entirely up to the justices to enforce and police. That I (or some of my academic colleagues or lower-court judges) might think particular cases are worthy of certiorari does not make it so—just as denials of certiorari prove nothing more than that at least six justices disagreed. My point is a more modest one: Insofar as folks, like Justice Gorsuch, might try to shift the responsibility for the Court’s shrinking docket away from the justices and to other actors, like lawyers not filing enough appeals, the data suggest, rather powerfully, that this claim is dubious at best—all the more so when those same individuals don’t identify the types of cases that they want to see more of.

Reasonable minds can disagree about whether the Court’s shrinking docket is a good thing (my own view is that there are lots of reasons why it isn’t); what cannot be denied is that, Justice Gorsuch’s comments notwithstanding, the justices are front-and-center in why it is shrinking—especially when it comes to “paid” cases, which are, and long have been, the bread and butter of the Court’s discretionary docket.

SCOTUS Trivia: Roberts Passes Rehnquist

Several folks already flagged this on Twitter, but over the weekend, Chief Justice Roberts passed his former boss, Chief Justice Rehnquist, for the fourth-longest tenure as Chief Justice of the United States (Rehnquist is still eighth on the all-justice tenure list, given his extra 14.5 years as an associate justice). Of the 17 men to hold the office (I’m still holding out for Evelyn Baker Lang), only Melville Fuller, Roger Brooke Taney, and John Marshall are still ahead of Roberts.

If things continue apace, Roberts would pass Fuller for third place in late June 2027; Taney in April 2034; and Marshall on (if my math is right) February 29, 2040 (when he’d be 85). The really remarkable trivia here, it seems to me, is how long both Marshall and Taney held the Court’s center seat—especially given then-prevailing life expectancies. From February 4, 1801 to October 12, 1864, the nation had only two Chief Justices. During that same stretch, we had 14(!) presidents.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone next Monday!

Happy Monday, everyone. I hope that you have a great week!!

It’s theoretically possible that the Court could still hand down more signed opinions in argued cases during its current term (e.g., if it granted some appeal on an insanely expedited basis and had it argued and decided between now and October 6). But I think it’s safe to assume that we’ve seen the last OT2023 decisions in argued cases.

All of the data in this post comes from the statistics compiled in the Court’s annual Journal—each installment of which is available via the Court’s website.

Beating an old (and very dead) horse, it sure would be nice if the justices allowed for public recordings of their public comments…

There is also the Court’s “original” docket—which the Court’s data includes in its “paid” category. But those numbers are small enough to not affect the overall analysis one way or the other.

Today, September 9th, we celebrate “National When Pigs Fly Day”.

“National When Pigs Fly Day is a day for dreaming big and thinking about possibilities. It’s a day to imagine a future that may seem impossible or absurd and take small steps towards making it happen. It’s a day to think outside the box, take risks, and make things happen. The idea behind National When Pigs Fly Day is to make people set their sights higher and never give up.”

~ from National Today website

Love your Monday posts! When you explain at the beginning what you post when, you said you “post every Monday (including holidays like today)”, so I wondered what today’s holiday was, & looked it up. I thought it was great to see that today we are celebrating hope & that all things are possible! Cheerful news that democracy will win out & gloom, doom, & fascism will be soundly defeated! 🤩🤩🤩

One of the Trump justices insulting our intelligence with a misleading argument? How surprising!