94. Student Loans and the Shadow Docket

The latest battle over student loans to reach the justices underscores the procedural, substantive, and optical consequences of how the Court has routinized emergency applications

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current work, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

I was already planning to use this week’s “Long Read” to provide a deep dive into the rapidly evolving litigation challenging the latest efforts by the Biden administration to ease the repayment of student loans, and then the Eighth Circuit stepped in Friday night with a nationwide “injunction pending appeal,” which in turn provoked one of the more … striking … filings I’ve seen from a state’s lawyers respecting an emergency application.

To make a long story short, how we got to today is quite complicated, but the short version is not only that the Biden administration’s latest efforts have been temporarily blocked, but that Texas’s Solicitor General is asking the Court to block them permanently—without even holding oral argument. That this is where we are says a lot not just about the signals the justices have sent, but the errors the justices have made through their own behavior respecting emergency applications in recent years.

But first, the news.

On the Docket

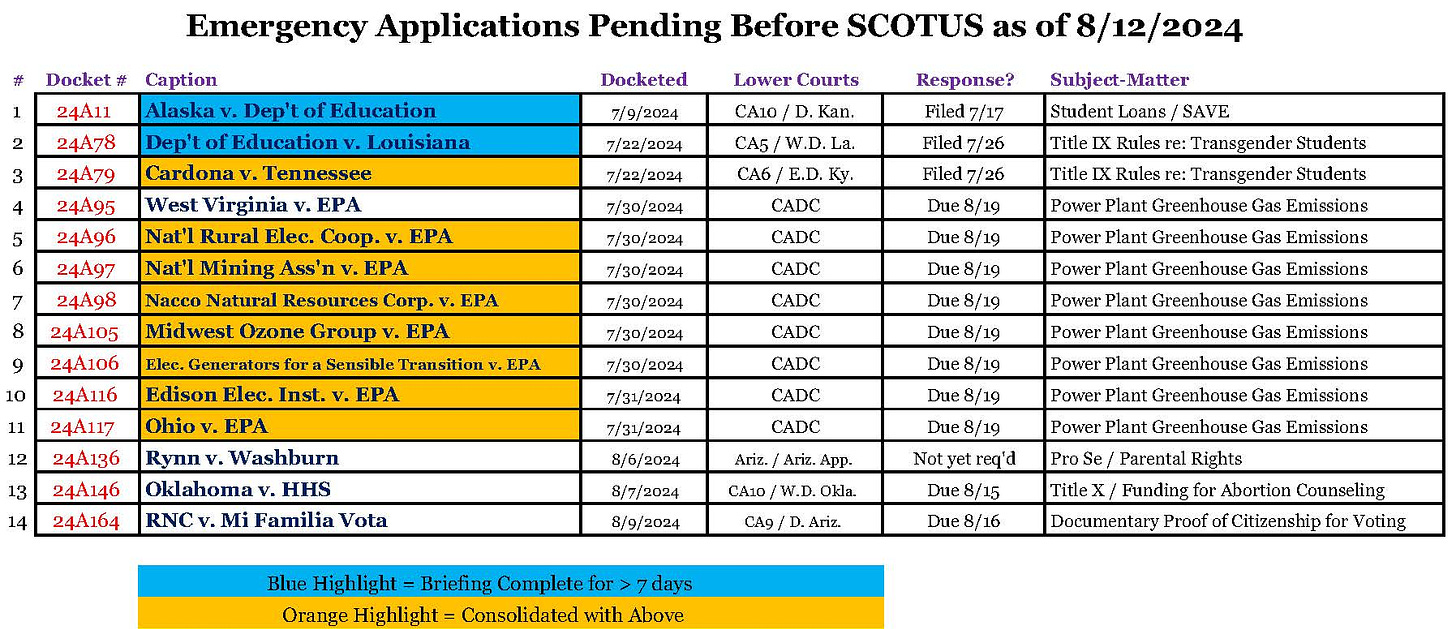

The Court didn’t do very much last week—either in general or specifically to relieve the glut of pending emergency applications, a total that is now up to 14, 13 of which are of national significance. As expected, the Court summarily denied Missouri’s request to not just bring a new original complaint against New York, but to block the gag order and impending sentencing of former President Trump for his New York state conviction. Justices Thomas and Alito repeated their long-articulated (if analytically unpersuasive) view that the Court must hear such suits, although they went out of their way to stress that they “would not grant other relief.” The Court also refused to block Texas’s execution of Arthur Burton, over no public dissents. But that was it.

Meanwhile, in addition to all of the major emergency applications that were already pending, the Court received its first major 2024 election-related application—this one from the Republican National Committee and two Arizona state legislators, asking the justices to put back into effect Arizona laws that require documentary proof of U.S. citizenship for both voting by mail and voting in person. Justice Kagan ordered those challenging the Arizona laws to respond by 4 p.m. (ET) on Friday, August 16. With the RNC arguing that the deadline for printing the proper federal ballots is next Thursday, August 22, this dispute will likely also provoke a quick turnaround.

In case you’ve lost track, here’s my current list of all of the pending emergency applications:

The Title IX and student loan applications are, quite obviously, ripe for a decision sometime this week. As for what’s going on in the latter of those disputes, well, read on.

The One First “Long Read”: Student Loans, Redux

As folks likely recall, last June, in Biden v. Nebraska, the Supreme Court, by a 6-3 straight-ideological-line vote, threw out the Biden administration’s student loan debt forgiveness program—which had been adopted under the HEROES Act of 2003. Whatever one thinks about the Court’s analysis of the Department of Education’s statutory authority, I still haven’t seen a compelling defense of the Court’s deeply flawed holding that Missouri had standing to challenge the program in the first place.

Well, student loans are back before the Supreme Court. And according to three red states, led by Texas, the latest efforts by the Biden administration are a transparent attempt to sidestep the Court’s ruling from last June. It turns out that things are quite a bit more complicated—including the procedural morass in which the justices now find themselves.

Let’s start with the federal program being challenged.

Since 1993, Congress has authorized the Department of Education to lend money directly to student borrowers. The same statute requires the Department to give borrowers options for how to repay those loans, including “an income contingent repayment plan, with varying annual repayment amounts based on the income of the borrower, paid over an extended period of time prescribed by the Secretary, not to exceed 25 years.”

The statute expressly delegates to the Secretary of Education the authority to decide (1) what the income-based repayment amounts should be; and (2) the relevant period of time, up to 25 years. The Department adopted plans to implement these statutory requirements in 1994, 2012, and 2015—all of which followed the same basic model: individual borrowers would have a repayment amount set that was based upon the Department’s determination of their “discretionary” (effectively, disposable) income; and, at the end of the repayment period, any amount that remained would be forgiven. As the Solicitor General has explained, “Under the 2015 [plan], for instance, the amount of income protected from loan payments was 150% of the federal poverty line and a borrower’s discretionary income was defined as the borrower’s adjusted gross income minus that protected amount. Monthly loan payments were capped at 10% of a borrower’s discretionary income. And borrowers could qualify for loan forgiveness after making payments for 20 or 25 years.”

Last June, perhaps with an eye toward the impending demise of the broader HEROES Act forgiveness program, the Biden administration adopted further amendments to the 1994, 2012, and 2015 regime. Again, quoting the SG: the new rule “increases the amount of income protected from loan payments to 225% of the federal poverty line (i.e., $32,805 for a borrower with no dependents using the 2023 level). It lowers monthly payments for undergraduate loans to 5% of a borrower’s discretionary income. It ‘provid[es] for a shorter repayment period and earlier forgiveness for borrowers with smaller original principal balances (starting at 10 years for borrowers with original principal balances of $12,000 or less, and increasing by 1 year for each additional $1,000 up to 20 or 25 years).’ And it gives the REPAYE plan a new name: the Saving on a Valuable Education (SAVE) plan.”

Off the bat, what should hopefully be clear is how different the SAVE plan is from the program the Court struck down last June. It comes from an entirely different statute (which doesn’t just authorize, but requires income-contingent repayment plans); it reflects amendments to a program that has been in effect continuously since 1994; and it ties forgiveness to different (and far narrower) eligibility and repayment criteria than anything that was true of the ill-fated HEROES Act program. (Forgiveness, it should be noted, that had been available under the pre-2023 iterations of the program, too.)

Nonetheless, the program was challenged by two coalitions of red states—both of which waited more than nine months to bring suit. 11 states sued in the District of Kansas; seven sued in the Eastern District of Missouri. And although Kansas and Missouri are right next to each other, they’re in different circuits. With apologies to the non-lawyer readers, what follows is a lot of messy legal procedure.

In the Kansas-filed case, the district court held that three of the 11 states (Alaska, South Carolina, and Texas) “just barely” had standing, while explaining that even those states’ standing was “more attenuated—and therefore weaker—than [Missouri’s] standing” in Biden v. Nebraska. On the merits, the court enjoined some parts of the rule but not others—concluding that, even though federal law expressly authorizes parts of the SAVE plan, the loan-forgiveness and payment-threshold provisions could not survive application of the “major questions” doctrine.

The federal government and the states both appealed. While that appeal was pending, the federal government sought—and received—a stay of the district court’s injunction from a divided Tenth Circuit panel. The Tenth Circuit set an expedited briefing schedule (which is now complete), and is set to hold oral argument on the cross-appeals on August 21, i.e., nine days from now. Nevertheless, the three states the district court held to have standing then sought emergency relief from the Supreme Court—asking the justices to vacate the Tenth Circuit’s stay. That application was filed on July 5—38 days ago. The Biden administration filed its response on July 17. And yet, it remains pending.

And then there’s the Missouri case. There, the district court held that Missouri, at least, has standing (for the same reason the Supreme Court held it had standing in Biden v. Nebraska), and that it was likely to succeed at least on its claims that loan forgiveness is not specifically authorized by statute and that the SAVE program in general is inconsistent with the major questions doctrine. The court only enjoined the loan-forgiveness provisions, though; it did not block the payment-threshold and non-accrual-of-interest provisions.

Both parties appealed. And, claiming that the Biden administration was defying the district court’s injunction, Missouri asked the Eighth Circuit for an “injunction pending appeal” to block not just the underlying program, but also the adjustments the Department of Education had undertaken after and in response to the district court’s injunction. On Friday, the Eighth Circuit acquiesced—issuing a nationwide injunction pending appeal barring the Department of Education from “any further forgiveness of principal or interest, from not charging borrowers accrued interest, and from further implementing SAVE’s payment-threshold provisions.” Just as it had in the HEROES Act case last year, the Eighth Circuit applied the wrong standard—analyzing Missouri’s request under the traditional factors for a preliminary injunction in a trial court, not the far stricter standard for an “injunction pending appeal” after a trial court declined to provide the requested injunction. I’ve written about how problematic that conflation is before; it’s rather alarming to see it surface yet again.

All of that brings us to the remarkable letter that the Solicitor General of Texas, Aaron Nielson, filed in the Supreme Court on Friday on behalf of the three states in the Kansas case. Nielson’s letter concedes, as it must, that the Eighth Circuit’s ruling largely moots the request for emergency relief in the Kansas case; most of what the applicants were seeking to block is now blocked. But rather than simply withdraw the application or invite the Court to deny it without prejudice, he doubled down:

the Eighth Circuit’s analysis underscores why the Court should grant certiorari before judgment and summarily order the district court to vacate the SAVE Plan, or at least set this case for argument (ideally in conjunction with the Missouri litigation to ensure all issues are covered). Moreover, expediting a decision will not prejudice the federal government, which has indicated it may seek relief from this Court within 10 days. Unfortunately, until this Court holds (again) that “‘the basic and consequential tradeoffs’ inherent in a mass debt cancellation program ‘are ones that Congress would likely have intended for itself,’” 600 U.S. at 506, it is increasingly plain that the federal government will continue to try give away nearly a half trillion dollars of the public’s money.

This is a remarkable thing for any lawyer to tell the Court, let alone a lawyer representing a state.1 First, there’s the substantive effort to tie the SAVE program to the same mast as the HEROES program (including the quote from Biden v. Nebraska, never mind the myriad (and germane) statutory differences. Second, there’s the procedural hubris of asking the Court to not only grant certiorari before judgment in the Kansas case (something that used to be rare, but has become more common lately as an alternative to resolving these kinds of disputes through emergency applications), but to dispose of the merits summarily (something it has done on certiorari before judgment exactly once in its history—and not to its credit). More than that, neither the district court in the Kansas case nor the district court (or Eighth Circuit) in the Missouri case granted the relief Nielson’s letter seeks—full vacatur of the SAVE program. In other words, Texas is telling the Court that it should summarily grant even broader relief than any lower court granted.

And then there’s the broader optics of the whole affair—states that even a sympathetic district judge held “just barely” have standing; a court of appeals issuing an “injunction pending appeal” by applying the far lower standard for a preliminary injunction; and Texas telling the Supreme Court there’s no need to even give plenary review to the federal government in its challenge to a significant federal program that has a far clearer basis in the relevant statute than the loosely analogous one that a divided Court struck down 13.5 months ago.

Whatever one thinks about the legality of the SAVE program, or the policy wisdom of loan forgiveness as a federal regulatory priority, or even the major questions doctrine in the abstract, what should be clear is that this kind of state-driven, hair-on-fire emergency litigation is something that the Supreme Court has affirmatively enabled through its behavior in recent years—much like the Court’s own misapplication of the proper standard of review has been reflected in some of these very lower-court rulings. Once again, the mess in which the Court currently finds itself is largely one of its own making.

SCOTUS Trivia:

The Recess Appointment of John Rutledge

I’ve been saving for a time when things calm down (LOL!) a deep dive into the messy question of how “recess appointments” of Supreme Court justices comport with the “Good Behavior” Clause of Article III—i.e., how it’s constitutional to have justices whose commissions will necessarily expire upon the end of the next congressional session unless they are previously confirmed by the Senate. (Folks with better memories than mine might remember that I wrote about this subject briefly back in September 2023.) Believe it or not, there have been 12 recess appointments of justices—the most recent in 1958.

I mention it here because today is the 229th anniversary of the most significant recess appointment of a justice—when President Washington appointed former Associate Justice John Rutledge to fill the seat vacated by Chief Justice John Jay on June 28, 1795, upon the latter’s election as Governor of New York. With the Senate out of session from June 26-December 7, and with the Court soon to return to Philadelphia for its then-regular August sitting, Washington named Rutledge as the nation’s second Chief Justice on June 30, 1795—and Rutledge took the oaths of office, thereby ascending the bench, on Wednesday, August 12.

Unfortunately for Rutledge, on July 16, he had given a speech in which he had been severely critical of (and forcefully denounced) the Jay Treaty—which the Senate had just ratified on June 24. Thus, shortly after the very same Senate returned on December 7, it voted down Rutledge’s formal permanent nomination to become Chief Justice, still the only formal rejection in Senate history of (1) a recess-appointed justice; or (2) a nominee to be Chief Justice (Abe Fortas withdrew). Rutledge resigned on December 28—rather than continue to serve through the end of the Senate’s session the following June, as he arguably could have under the Recess Appointments Clause. To smooth things over with the Senate, Washington nominated one of their own—Connecticut’s Oliver Ellsworth, author of the Judiciary Act of 1789—to become the third Chief Justice. He was confirmed by a voice vote one day later.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone next Monday!

Happy Monday, everyone. I hope that you have a great week!!

This may be pedantic, but there’s also the letter’s “cc” line, which refers to the Solicitor General as “Elizabeth B. Prelogar,” rather than as “Hon. Elizabeth B. Prelogar.” I had always been taught that those holding elected or appointed office—like the Solicitor General of Texas—are entitled to the honorific. But what do I know?

As a parent of a newly graduated student who is currently enrolled in the SAVE program, I can’t say how much I appreciate your explanation/summary of this complicated, convoluted legal argument. Though am pretty depressed after reading this, thank you very much for the understandable-to-a-layperson info😉

Steve,

Wow. Very impressive dissection of the issues and adjacent rulings, pertaining to the circuit's arguments and SCOTUS's docket. Happy Monday indeed. We are in this together.