86. What's Left for OT2023

Even after handing down nine decisions last week, the justices still have a lot to resolve before rising for their summer recess. Here's what we know for sure, and what I think, about what comes next.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Given everything that’s going on, I thought I’d abandon the usual format this week in favor of an issue that’s focused on just two things: Summarizing what the Court did last week (a lot); and previewing what’s still coming this week and, perhaps, early next week (even more). It’s no exaggeration to suggest that the next 5–8 days are likely to produce as much significant Supreme Court news as we’ve seen in a long time, and so just trying to keep up with all of it seems a worthwhile endeavor unto itself.

Last Week

Last Monday’s regular Order List came with four more grants of certiorari, albeit none in especially high-profile cases. That brings the total for OT2024 to 16 cases—which is still quite a bit short if the justices intend to fill their fall calendar before rising for their summer recess. We could get more grants today, but it also looks increasingly likely that the justices are going to use the “Clean-Up Conference” (about which I’ll have a lot more to say, perhaps as soon as next Monday) to add cases with sharper political/ideological valences to their docket.

The big news last week, of course, were the nine rulings that the Court handed down across two days (Thursday and Friday). Many, if not most, of these rulings deserve their own newsletter treatments, and I’ll aim to catch up a bit over the summer. But given some of the divisions among the justices even in these cases, it sure seems likely that we’re heading for quite a slew of bitterly contested decisions between now and the end of the October 2023 Term.

In brief (for now), the nine rulings, in the order in which they were handed down, were:

Moore v. United States: In a case that sure appeared to be designed to set up a constitutional argument against a “wealth” tax, the Supreme Court avoided any big pronouncements one way or the other, while upholding the “Mandatory Repatriation Tax.” Justice Kavanaugh wrote for a five-justice majority. Justice Barrett wrote an opinion concurring in the judgment, in which Justice Alito joined. Justice Thomas wrote the dissent, which was joined by Justice Gorsuch.

Chiaverini v. City of Napoleon: For a 6-3 majority, Justice Kagan held that the presence of probable cause for one charge in a criminal proceeding does not categorically defeat a Fourth Amendment malicious-prosecution claim relating to another, baseless charge, making it somewhat easier for criminal defendants to seek damages when prosecutors go too far. Justice Thomas and Justice Gorsuch each wrote dissenting opinions, with Justice Alito joining the former.

Diaz v. United States: In a messy case about Rule 704(b) of the Federal Rules of Evidence, Justice Thomas wrote for a 6-3 majority in holding that expert testimony that “most people” in a group have a particular mental state is not an opinion about “the defendant,” and can thus be admitted without violating Rule 704(b). (So, testifying that “most” drug mules are aware that they’re transporting drugs can be admitted as expert testimony in a case in which a defendant charged with drug trafficking argues that they didn’t know.) Although it might seem at first blush like this rule is deeply pro-prosecution, Justice Jackson’s concurring opinion highlights some ways in which the decision might also benefit defendants. Justice Gorsuch wrote the dissent, which was joined by Justices Sotomayor and Kagan.

Gonzalez v. Trevino: Speaking of messy, the Court handed down an unsigned “per curiam” opinion in Gonzalez—holding, in just over four pages, that the Fifth Circuit had misapplied a 2019 decision, Nieves v. Bartlett, about the proper standard for a plaintiff to prove a retaliatory arrest claim. What’s weird about this disposition is the separate opinions: A 16-page concurrence from Justice Alito; a two-page concurrence from Justice Kavanaugh wondering why the Court took the case in the first place; a two-page concurrence from Justice Jackson (joined by Justice Sotomayor) largely pushing back against Alito; and a four-page dissent from Justice Thomas. My best bet, which isn’t worth very much, is that Alito’s concurrence was originally a majority opinion, but he couldn’t hold a majority together, and so a cryptic, narrow, unsigned remand was a compromise that every justice except Thomas could get behind. Your mileage may vary, but if this is how the Court is dividing even in cases with relatively low stakes… (of note, if this is right, it also makes it all-but certain that Justice Barrett received the initial majority assignment in Murthy v. Missouri—the only case left from March. She’s the only other justice without a March opinion yet.)

Texas v. New Mexico: Speaking of dividing in cases with relatively low stakes, the Court on Friday decided its lone “original jurisdiction” case of the term, sustaining the federal government’s objections to a proposed consent decree between Texas and New Mexico in a long-running water-rights dispute. Justice Jackson wrote for a 5-4 majority; Justice Gorsuch’s dissent was joined by Justices Thomas, Alito, and Barrett.

Dep’t of State v. Muñoz: One of the more significant rulings from the Court last week, a 5-3 majority (with Justice Gorsuch concurring in the judgment on narrower grounds) held that a U.S. citizen does not have a fundamental liberty interest in her noncitizen spouse being admitted to the country—so that the government doesn’t have to provide almost any process (or any but the most conclusory of reasons) in refusing to allow the noncitizen spouse to re-enter the country. Justice Barrett wrote the majority opinion; Justice Sotomayor wrote a stern dissent, joined by Justices Kagan and Jackson, raising alarm bells about what the majority opinion means for the right to marry, especially as between same-sex partners. Whether the majority opinion has implications beyond immigration law remains to be seen, but even within immigration law, it could have remarkably disruptive effects on multinational marriages.

Erlinger v. United States: Speaking of waiting to see the long-term implications, the Court in Erlinger held that the Fifth and Sixth Amendments require that a jury, rather than a judge, determine beyond a reasonable doubt whether a criminal defendant’s prior offenses were committed on “separate occasions,” as required for a particular sentencing enhancement under the federal Armed Career Criminals Act. Justice Gorsuch wrote for a 6-3 majority, holding that the result followed from a line of the Court’s cases, dating back to Apprendi v. New Jersey in 2000, which have taken a formalist turn toward the right of defendants to have all facts that could contribute to their conviction or enhance their sentence found by a jury, rather than a judge. And although Justice Kavanaugh’s objections to that result in his dissent (joined by Justice Alito) are not especially surprising, the fact that Justice Jackson joined part of that dissent (and wrote one of her own) is. Perhaps her experience as a district judge has given her more faith in having these issues resolved by judges than by juries. Either way, it opens up interesting questions about the future of the Apprendi line of cases.

Smith v. Arizona: Justice Kagan wrote for the majority in another messy case about expert evidence—holding that, if an expert conveys an absent analyst’s statements in support of his opinion, and the statements provide that support only if true, then the statements come into evidence for their truth—meaning that, if they are “testimonial” (which the Court did not decide), then their admission would violate the defendant’s rights under the Sixth Amendment’s Confrontation Clause. Four justices (Sotomayor, Kavanaugh, Barrett, and Jackson) joined Kagan’s opinion in full; two (Thomas and Gorsuch) joined it in part; and Justice Alito concurred in the judgment—in an opinion joined by Chief Justice Roberts. One small note: Although I think it’s a broadly held view that Justice Kagan is just about the best writer on the current Court, opinions like this one really help to drive home why. Here’s a complicated dispute arising out of the Court’s own complicated doctrine, and whether you agree with Kagan’s approach or not, you’ll have a pretty good idea of how we got here and what the stakes are by the time you’re done.

United States v. Rahimi: Last, but certainly not least, came the much-anticipated decision about whether the federal ban on possession of firearms by those currently subject to domestic violence-related restraining orders violates the Second Amendment.1 As you’ve no-doubt heard by now, Chief Justice Roberts, writing for an 8-1 majority, upheld the federal ban in another decisive, cross-ideological repudiation of the Fifth Circuit. There is a lot to say about the majority opinion—how it tries to narrow Bruen; how it blames lower courts for misreading Bruen (umm…); and what it portends for future challenges to other federal criminal prohibitions and other gun control measures. I hope to devote a future issue to a deeper dive. For now, let me just offer two quick points: First, given that the eight justices in the majority produced six separate opinions, I don’t think anyone can be especially confident about what this ruling portends for other cases—like the challenge to the federal ban on gun possession by all convicted felons, or by those convicted of particular drug offenses (like Hunter Biden). The Court is going to have to take those cases, too—and we might see, as early as today’s Order List, whether the justices are inclined to take them directly, or to vacate and remand the lower-court rulings from which appeals are pending for reconsideration in light of Rahimi, kicking the can down the road a year or two. Second, Rahimi doesn’t just help to underscore what was so problematic about Bruen; it also, in my view, represents close to a 180-degree turn from one of the central justifications the Court deployed back in 2008 in Heller, when a 5-4 majority first held that the Second Amendment protects a right to private self-defense in the first place. For Justice Scalia, the Court could put aside the Second Amendment’s “prefatory” clause (“A well-regulated militia…”) because the “operative” clause was so clear that it covered private self-defense. But Rahimi is largely about why historical context is relevant to resolving debates over the scope of the Second Amendment—and when private self-defense can yield to public safety. If one concedes that there are relevant debates over the provision’s scope, then it sure seems to me that one is also conceding that the prefatory clause may not be so irrelevant after all.

And that brings us to this week…

This Week (and Beyond?)

If you’re still reading, thanks. With all of that last week, here’s what we know, and what I think, about what’s coming—and when:

First, we know that the Court will issue a regular Order List at 9:30 ET. John Elwood’s indispensable “Relist Watch” previews some of the possible cert. grants that we could see. And as noted above, I’m especially interested in what the Court does (if anything) with gun cases it had clearly been holding for Rahimi. We may not find that out today, but we might get some clues. Of note, this is the last regular Order List we expect before the list that comes out of the “Clean-Up Conference,” discussed in more detail below. So it could be quite busy.

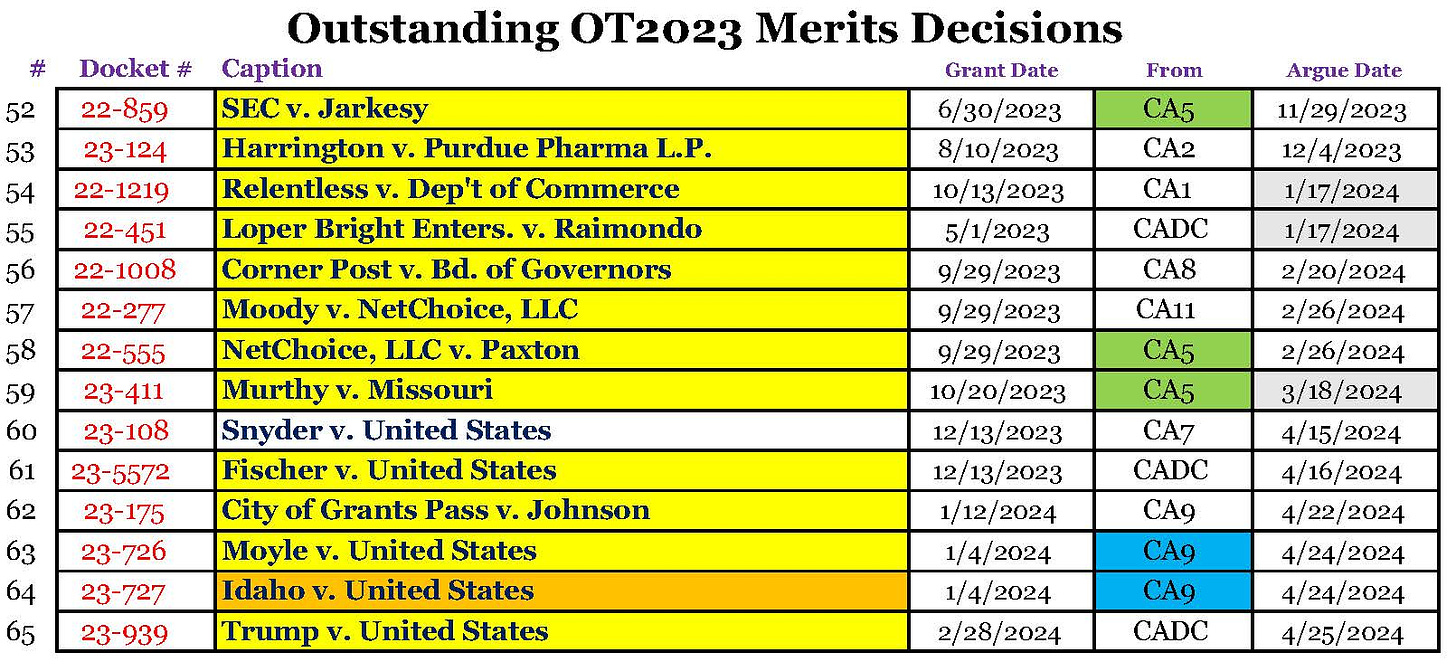

Second, we know that the Court is handing down opinions in argued cases Wednesday at 10:00 ET—and we know that the Court is not handing down all of its remaining decisions (not just because of how many there are, but because the Court usually gives the press a heads-up about which day is the last). At this point, just about everything that’s left is a major case (yellow shading):

And this list doesn’t even include the ozone pollution emergency applications—which, somehow, are still outstanding.

But, strangely, we have no further intelligence, at least as of now, about other hand-down days. We know we’re not getting opinions today; and I’d be shocked if the Court belatedly added tomorrow. But it’s odd that the Court hasn’t announced yet that it’s handing down decisions on Thursday and/or Friday, too. Just doing some math, the only way for the Court to finish this week would almost certainly require it to hand down rulings on all three of those days (Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday). That the Court hasn’t yet announced that this is, in fact, the plan suggests at least a decent possibility that it might not make it—and that we might be heading into early next week (i.e., July), as well. Indeed, the fact that the Court is rolling out its schedule so piecemeal suggests that it doesn’t know—perhaps because the justices are still at loggerheads in at least some of the remaining cases. That’s the real wild-card here, and also why all we can do from the outside is speculate. My best guess, again, for what little it’s worth, is that we’ll get opinions at least one other day this week (Friday?), and then we’ll learn by the end of the week that next Monday or Tuesday will be the last day.

One other point on the timing: The justices don’t skip town the second the last opinion is read from the bench. Rather, they meet for the so-called “Clean-Up Conference,” at which they dispose of just about order that is still pending (and ripe). That means not only a bunch of cert. grants, but also denials with some testy dissents; and, at least in some recent years, controversial summary dispositions (where the Court issues an unsigned opinion resolving the merits at the certiorari stage—without full briefing or argument). That process also takes time—which, to me, will make it only that much harder for the Court to wrap up this week. But whether the Court rises for its summer recess this Friday or early next week, we’re in for some massively important rulings between now and then.

Finally, the emergency docket, which has been unusually (and blissfully) quiet much of the last two months, may also produce some news this week—with Steve Bannon filing an emergency application seeking to put off his federal prison sentence for contempt of Congress, which is set to begin July 1, while he appeals. Readers might recall Peter Navarro’s similar effort back in March—which resulted in a rare in-chambers opinion from Chief Justice Roberts, denying the application without prejudice to Navarro’s right to fully appeal his conviction from behind bars. It seems to me that we might see a similar outcome here—although unlike Navarro, Bannon at least picked off one vote in the court of appeals (which denied his emergency application, 2-1). The Chief Justice has ordered the federal government to respond to Bannon’s application by 4 p.m. (ET) on Wednesday, so here’s something else the Court will have to deal with this week.

Yikes.

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one. This week’s bonus issue drops Thursday morning (odds are pretty darn high that it will be devoted in some respect to some or all of Wednesday’s rulings). And, of course, we’ll be back with a regular issue next Monday.

Until then, happy Monday, everyone. I hope that you have a great week (and that you, unlike the justices, meet your self-imposed deadlines)!

Rahimi was last only because it was the Chief Justice who wrote the majority opinion—and, with the Court handing down rulings in reverse order of seniority, the only opinions that can come after the Chief Justice’s are those that are unsigned.

What’s the color code for the table?

How often has the SC, in recent years gone past the 4th of July for the clean up conference?