80. Louisiana's Congressional Map Comes Back to the Court

Two overlapping emergency applications are once again asking the justices to effectively decide which party will control one of Louisiana's six House seats

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us. We crossed the 30,000-subscriber mark last week, and I continue to be grateful to all of you for reading, subscribing, sharing, and everything else you do to support this project.

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current work, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

As we start getting into the groove of regular decisions from the Court in argued cases, this week’s issue takes a brief detour to focus on two overlapping emergency applications, both of which arise from ongoing litigation over the shape of Louisiana’s congressional districts—and the resolution of which could go a long way toward resolving whether a Democrat or a Republican will be elected from Louisiana’s newest House seat.

But first, the news.

On the Docket

There was no regular Order List last week, so the only formal rulings we got from the Court were the two opinions in argued cases that the justices handed down on Thursday (the 19th and 20th of the Term).

In Culley v. Marshall, Justice Kavanaugh held, for a 6-3 majority, that although the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment requires a timely hearing when a state seeks civil forfeiture of property seized during an arrest (like a car that a mom loaned to her son who was then arrested for possession of marijuana), that hearing does not need to be separate from the forfeiture proceeding itself. Thus, where, as in the two cases at issue, Alabama initiated forfeiture proceedings 10 and 13 days after seizing the petitioners’ cars during lawful arrests, Alabama did not violate due process. But although the decision ostensibly split the justices along ideological lines (with Justice Sotomayor writing on behalf of herself and Justices Kagan and Jackson in dissent), Justice Gorsuch penned a separate concurrence, joined by Justice Thomas, expressing serious doubt about the constitutionality of civil forfeiture both in general and in many of its applications. Gorsuch didn’t rely on those doubts here—which might’ve led him to side with the plaintiffs—because of “the way the parties have chosen to litigate this case” (as if that’s stopped him before). But the upshot is that there appear to be at least five votes willing to impose more rigorous constitutional limits on civil forfeiture in future cases—which, IMHO, would be a positive development.

And in Warner Chappell Music, Inc. v. Nealy, we also got a 6-3 decision, with Justice Kagan writing for the majority (and cogently summarizing both the issue and the holding), emphases mine:

The Copyright Act’s statute of limitations provides that a copyright owner must bring an infringement claim within three years of its accrual. In this case, we assume without deciding that a claim is timely under that provision if brought within three years of when the plaintiff discovered an infringement, no matter when the infringement happened. We then consider whether a claim satisfying that rule is subject to another time-based limit—this one, preventing the recovery of damages for any infringement that occurred more than three years before a lawsuit’s filing. We hold that no such limit on damages exists. The Copyright Act entitles a copyright owner to recover damages for any timely claim.

Justice Gorsuch wrote for the dissenters, which included himself and Justices Thomas and Alito. The whole thing is a pretty decent discussion of how time limits in copyright work (especially for fans of Flo Rida).

We expect a regular Order List (and possible grants of additional cases for next Term) this morning at 9:30 ET. We also expect one or more decisions in argued cases this Thursday at 10:00 ET, although it’s probably still too early for any of the really high-profile cases—especially those argued later in the Term.

But the Court is also likely to rule this week, perhaps by Wednesday, on two pending emergency applications, both of which arise out of the ongoing battle over congressional redistricting in Louisiana. And although there’s an important (and troubling) legal question underneath the two applications, there’s also the reality that, once again, the justices are being asked to effectively adjudicate which party will control a House seat through the shadow docket. And that’s the subject of this week’s “Long Read.”

The One First “Long Read”:

Louisiana Redistricting Redux

I. How We Got Here

Louisiana has six seats in the House of Representatives, a number it retained after and as a result of the 2020 Census. But when the Louisiana legislature re-drew the six district lines after the 2020 Census, it included only a single “majority-minority” district, even though 31.4% of the state’s population identifies as Black (a total that increased in 2020). That map was promptly challenged by Black voters in Louisiana, who argued, among other things, that it impermissibly diluted their votes in violation of section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In Robinson v. Ardoin, the district court agreed, and ordered the Louisiana legislature to redraw the map with a second majority-minority district. (Even the Fifth Circuit declined to stay that ruling.) But after the Supreme Court froze a similar order from Alabama in February 2022, the Court also put the Louisiana ruling on hold that June—meaning that, like Alabama, Louisiana used a congressional map in the 2022 midterms that lower courts had held to violate the VRA.

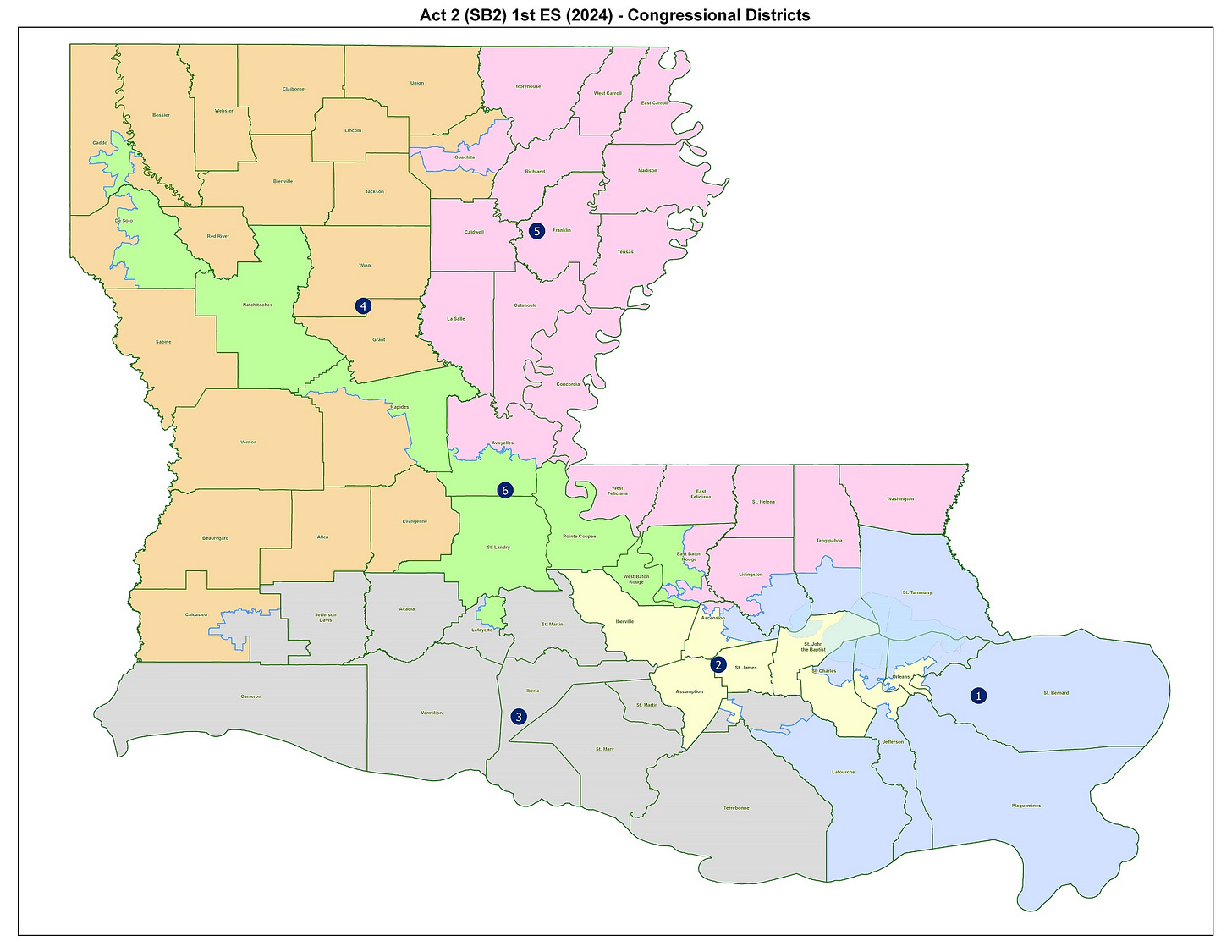

In June 2023, the Supreme Court decided Allen v. Milligan, in which it held that the Alabama district courts were correct that Alabama had to draw a second majority-minority district. It then dismissed the appeal in Robinson—sending the case back so that Louisiana could likewise draw a new map in time for the 2024 cycle. Louisiana did just that with the new sixth congressional district, which cuts across the state from Shreveport to Baton Rouge (in green below):

This new map, with a second majority-minority district, was promptly challenged by plaintiffs (who call themselves “non-African American voters”) on the ground that it represents racial gerrymandering in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment—even though it was only drawn this way to comply with section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, a statute that purports to enforce both the Equal Protection Clause and the Fifteenth Amendment.

On April 30, a three-judge district court1 sided with the plaintiffs. In a 2-1 decision (with two Trump-appointed district judges in the majority and Fifth Circuit Judge Carl Stewart in dissent), captioned Callais v. Landry, the court held that Louisiana had gone too far in trying to comply with section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, and had relied too heavily upon race without a sufficient justification for doing so in drawing the new map.

Putting aside, for the moment, the merits of the district court’s analysis (I’m with Judge Stewart), regardless of who’s right, the ruling poses a pretty significant remedial question: which map should Louisiana use in the 2024 election cycle? The one that, according to the district court in Robinson, violates the Voting Rights Act? Or the one that, according to the district court in Callais, violates the Equal Protection Clause? Or another one that the three-judge district court in Callais might endeavor to draw in the next few weeks? Complicating matters, the clock is ticking toward Louisiana’s candidate registration deadline in mid-June—meaning that whatever the answer is, someone needs to answer it, and right soon. (Louisiana says it needs to know by this Wednesday!)

II. The Two Emergency Applications

Enter, the emergency applications. Last Wednesday, the Robinson plaintiffs, who had intervened in the district court in Callais, asked the justices to put the three-judge court’s ruling on hold, arguing that, “without [the new map] in place for the 2024 elections there is a significant risk . . . that no VRA-compliant map will be in place for the 2024 elections.” And on Friday, the state joined the party, filing its own emergency application and suggesting that “This case screams for a Purcell stay,” i.e., a stay to prevent a district court ruling from interfering with election procedures too close to the relevant deadline. (For more on Purcell, see this prior issue of the newsletter.)

Justice Alito has called for a response to both applications by 11:00 ET today—suggesting that the Court may try to rule by this Wednesday. Whatever the Court does, it could have pretty significant ramifications both in the short term and going forward.

III. Why the Louisiana Cases Matter

Frankly, it’s hard to disagree with most of Louisiana’s position here, especially with respect to Purcell. One of the real problems with Purcell is that the Supreme Court’s use of it, especially during the 2020 and 2022 election cycles, left at least the perception that the justices were invoking it when it helped Republicans but not when it helped Democrats. (This is one of the central points I make in Chapter 6 of The Shadow Docket.) Here’s a context in which it would not only clearly help Democrats (a second majority-minority seat in Louisiana is likely to be a second Democratic seat in what’s currently a 5R-1D delegation; but in which the state itself, through its Republican Secretary of State and Attorney General, is asking for the relief. If anything, the Purcell argument is even stronger here because it’s the district court’s decision in Callais that introduces chaos—including the possibility that Louisiana won’t have any map to use for its 2024 congressional elections.

If anything is tricky about this, it’s the differences in the arguments being made by the Robinson plaintiffs and those being advanced by Louisiana. The Robinson plaintiffs, for instance, don’t make nearly as much out of Purcell—perhaps because the NAACP LDF and ACLU lawyers representing them are so bitterly opposed to Purcell in general, and didn’t want to endorse it here. Louisiana also argues, as a fall back, that even if it can’t use the new map, the Supreme Court should at least put the old map (the one that was blocked in Robinson) back into effect. The Robinson plaintiffs (who succeeded in getting that map struck down) quite obviously disagree. But with Louisiana aggressively urging the Court to issue a stay based largely on Purcell, these distinctions may not matter. At least on the stay, Louisiana and the Robinson plaintiffs are seeking the same primary outcome—the ability to use the new map this fall no matter what. And if, in the face of that agreement, the Court still doesn’t intervene given all of these circumstances, well, that would be quite a story unto itself.

Beyond a stay, Louisiana’s application also asks the Court to “note probable jurisdiction” (the equivalent of granting certiorari for the tiny category of appeals over which the Court still has mandatory jurisdiction) and set the case for argument this fall—presumably on both the narrow question (does Louisiana’s new map violate the Equal Protection Clause) and the broader one (how are states supposed to avoid vote-dilution claims under the Voting Rights Act without violating the Equal Protection Clause when drawing majority-minority districts). It’s not hard to imagine that, at least on the second question, there could be real divergence between voting rights groups and Louisiana.

Moreover, given that the Court could also soon be asked to decide whether section 2 of the Voting Rights Act can be privately enforced at all, noting probable jurisdiction here could set the stage for not just one, but two massive voting rights cases next term—and right smack-dab in the middle of the 2024 election season, to boot.

Oy.

SCOTUS Trivia: Louisiana’s Justice

With a Louisiana theme to today’s “Long Read,” it seems fitting to use the trivia to talk about the Pelican State’s lone Supreme Court Justice: Edward Douglass White.

The son of a congressman and Governor of Louisiana, White spent some of his teenage years (although there is debate as to just how much) fighting for the Confederacy, before entering post-war Democratic politics in Louisiana (White is one of three justices to have served in the Confederate military, along with L.Q.C. Lamar and Horace Lurton). After stints both in the Louisiana State Senate and on the Louisiana Supreme Court (and, according to many accounts, in the KKK), White started earning national attention when he was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1891—so much so that, after President Cleveland’s first two nominees to succeed Justice Samuel Blatchford failed, he elevated White in 1894 at least in part because Cleveland was (correctly) confident that White’s fellow Senators would confirm him.

My own vote for White’s biggest impact on the Court stems from the circumstances of his confirmation to the Court’s center seat in 1910. White was the first sitting associate justice to ever be elevated to the Court’s center seat (Stone and Rehnquist have since followed him). And, at least at the time, White was also the oldest nominee in the Court’s history. As the story goes, this was all on purpose—an effort by then-President William Howard Taft to appoint a Chief Justice whom Taft himself might succeed. Remarkably, that’s exactly how it transpired; White passed away on May 19, 1921—just two months into the presidency of Taft’s fellow Republican (and fellow Ohioan), Warren G. Harding. Harding, in turn, nominated Taft to replace White—helping to set the stage for some of the most transformative reforms in the Court’s history.

Given all of that, it’s interesting to think about how different the Supreme Court might look today had Taft nominated someone else in 1910, or had White passed away (or stepped down) during Woodrow Wilson’s two-term presidency.

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one. This week’s bonus issue, which will mark the first anniversary of the publication of The Shadow Docket, drops Thursday morning. We’ll be back with a regular issue next Monday.

Until then, happy Monday, everyone. I hope that you (and the Knicks and the Rangers) have a great week!

Unlike the statutory challenge to the post-2020 map in Robinson (which was assigned to a single-judge district court), the plaintiffs’ constitutional challenge in Callais had to be assigned to a three-judge court under 28 U.S.C. § 2284.

Re: Edward Douglass White: I would have thought you’d mention his jurisprudence in the Income Tax and Insular Cases as well.

I can think of at least one other justice from Louisiana! She's currently on the court :p