79. 42(ish) Decisions to Go...

With scheduled arguments for the October 2023 Term in the rearview mirror, an overview of the work that the Supreme Court has in front of it over the next eight(-plus) weeks

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current work, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

We’ve reached that point of the Supreme Court’s annual calendar when the justices are directing most of their resources toward producing written opinions in each of the outstanding cases that have been argued since October. To that end, I thought it would be helpful to provide a quick and dirty overview of exactly what the Court has left to resolve between now and the justices’ summer recess—with some thoughts on the likely timing, as well. But first, the news.

On the Docket

As predicted, last week was relatively quiet at One First Street, N.E. The biggest news came in Monday’s regular Order List, when the Court, for the second week in a row, doubled the number of cases on its October 2024 Term merits docket—granting certiorari to take up four new disputes, albeit none that are likely to end up among the more significant cases from OT2024:

Medical Marijuana, Inc. v. Horn: This is a case in which the caption makes the dispute sound much more interesting than it really is. The underlying question is about where the line is, for purposes of civil damages under the federal Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) statute, between personal injuries (which fall outside of RICO) and injuries to “business or property” (which can be redressed under RICO).

Bouarfa v. Mayorkas: This is a technical dispute over whether courts can review the government’s decision to revoke an immigrant visa on the ground that it had initially misapplied nondiscretionary criteria in granting it. Lower courts said “no,” even though the applicant would have had a right to review of an initial decision denying review of the application (so it seems kind of odd that they’d lose that right just because the government wrongly approved, and then revoked, their visa).

Royal Canin U.S.A. Inc. v. Wullschleger: This case seems straight out of a Civil Procedure exam: When a plaintiff files a suit in state court that a defendant removes to federal court on the ground that it presents a federal question, can the plaintiff, now in federal court, amend their complaint to remove the federal question and then seek remand of the dispute to state court? (The Eighth Circuit said “yes.”)

Bufkin v. McDonough: This is a veterans’ case in which the dispute is over exactly how courts are supposed to enforce the “benefit of the doubt” rule—the statutory requirement that, in reviewing claims by veterans, courts are supposed to “take due account of” whether the executive branch gave the “benefit of the doubt” to the veteran.

Besides Monday’s Order List, there was only a single ruling from the full Court last week—an unexplained denial of an emergency application in Free Speech Coalition v. Paxton, in which the justices refused to freeze a Fifth Circuit decision that had rejected a First Amendment challenge to a state-law age-verification requirement for commercial websites that contain sexual content. (In other words, the justices left that requirement in effect.)

Because the justices did not hold a Conference last week, we do not expect a regular Order List later today. Instead, the only formal action we expect from the Court will be this Thursday, when the justices are expected to take the bench at 10 ET and hand down one or more decisions in argued cases. As even casual Supreme Court followers likely know, other than on the very last day of the term (when the process of elimination does the work), we never know in advance which decisions are coming on a given day (or even how many decisions are coming). But if we look at what’s left from this term’s arguments, we can start to see some patterns—hence the focus of this week’s “Long Read.”

The One First “Long Read”:

Taking Stock of OT2023

Entering this week, the justices have handed down 18 “merits” rulings—i.e., decisions resolving cases in which the Court granted certiorari and held argument. Other than the decision in the Colorado ballot disqualification case, I think it’s safe to say that none of these have been among the more significant rulings on the OT2023 calendar.

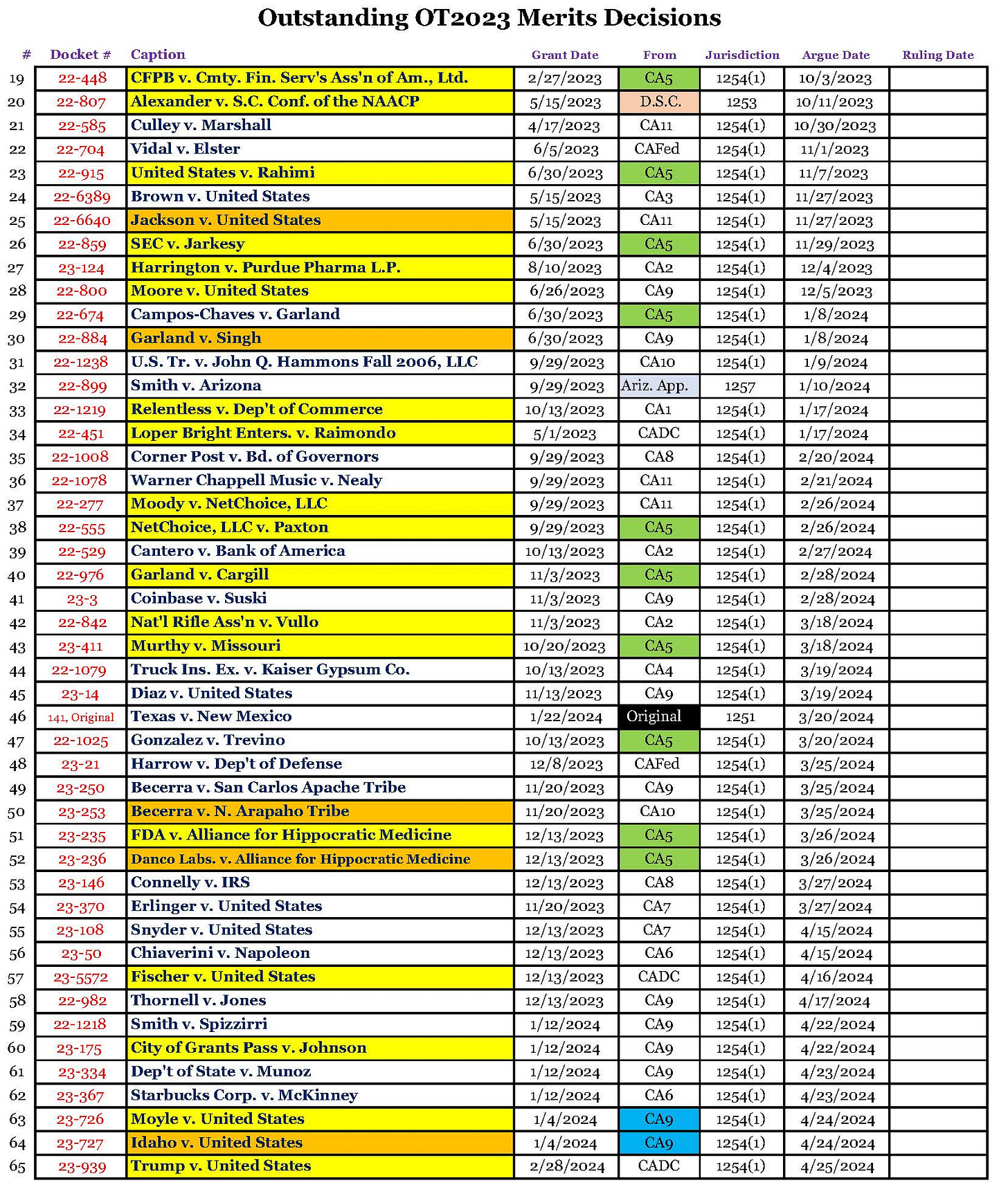

That leaves 47 such cases left to be decided, along with the “Good Neighbor” ozone pollution cases—which were argued back in February, but came to the Court as emergency applications, and so won’t be “merits” rulings in the same sense. In other words, between now and when the justices rise for their summer recess, we expect decisions in 48 cases to come from the bench—47 merits rulings, and one ruling on emergency applications.

But it almost certainly won’t be 48 decisions. Of the 47 granted cases, fully 10 of them represent five pairs of disputes that were consolidated for the purposes of both briefing and oral argument (e.g., the mifepristone and EMTALA cases). It’s always possible that the Court would de-consolidate the cases if there was some reason to resolve them separately (my very first argument, back in 2018, resulted in three decisions). But I don’t think it’s likely here. So assuming the Court hands down one opinion for each pair, that drops us to no more than 42 decisions in merits cases, plus the “Good Neighbor” applications.

And among those 42 decisions, there are at least two pairs of cases that were not consolidated for purposes of briefing and argument, but that could easily be decided through a single ruling if the justices were so inclined—the two NetChoice cases (about the Florida and Texas laws restricting content moderation by social media platforms) and the two cases about the future of Chevron deference (Loper Bright and Relentless). All of this is a long way of saying that, in my view, the most likely n among what’s left is somewhere between 40–42 merits decisions and the “Good Neighbor” applications.

There are two reasons why I think that number is worthy of pointing out. First, it means that, at the most, we’re looking at 60 merits decisions from the Court during its October 2023 Term. That would be the fifth term in a row in which the justices decide 60 or fewer cases—which is remarkable when one considers that, before the OT2019 Term, the last time the Court decided so few cases was in 1864. I’ve written before about the indisputable factual reality, and some of the serious consequences, of the Court’s shrinking docket; here, we see it in the flesh.

Second, and militating somewhat in the other direction, a remarkable percentage of those 40–42 merits decisions are going to be really important. Although any criteria for importance will necessarily be subjective, my own math is that at least 19 of the rulings still to come are of national significance. It’s the 18 cases in yellow highlight in the below list of what’s left (sorted by the date of oral argument), plus, again, the “Good Neighbor” ozone pollution ruling:

Why does this matter? In a typical term, the Court has somewhere around a dozen cases meeting this (highly subjective) criteria—and, by May, it has usually decided at least a couple of of them. That means that, in the last few weeks of the term, we’re liable to get only 5–10 potentially landmark rulings. Here, we have twice as many potentially major cases, none of which, with the exception (again) of the Colorado ballot case, have been decided. In other words, we’re likely going to have an unusually high concentration of major decisions from the Court between this Thursday and the end of June—skewing heavily toward the end of June.

In one sense, this is how things always go with the flow of decisions, at least in recent years. Having the term end with a couple of weeks of blockbuster rulings has been the standard for as long as I’ve been tracking the Court. (In earlier times, it wasn’t always so; Brown v. Board of Education came down on May 17; Roe v. Wade came down on January 22, albeit after re-argument.) But there’s a meaningful difference, in my view, between having a half-dozen major rulings come out over the last two weeks versus a dozen (or more). Not only does it suggest that the justices themselves will be forced to divide their finite resources even more thinly across a larger number of decisions in which they have ended up at loggerheads, but it also makes it more difficult for the public to fully appreciate the significance of what the Court is doing when, on the same day, it hands down a slew of major decisions.

The Court itself seems to be at least somewhat aware of, and responsive to, this last concern; it at least appears to stagger the release of the term’s biggest decisions so that they don’t all come at once. Last year, that meant that the five biggest decisions of the term—student loans; affirmative action; immigration enforcement discretion; independent state legislature; and 303 Creative—were spread across four different decision days. Ditto OT2021, when Bruen, Dobbs, and West Virginia v. EPA were each handed down on different dates. But unless the Court is literally going to sit every day during the last two weeks of June, that just may not be possible this term—with such a critical mass of high-profile rulings still to come.

One possible way for the Court to avoid such a pile-up is to get more of these rulings out faster. As of now, though, the only publicly announced days on which the justices are set to take the bench are each of the next seven Thursdays. Given that the Court to this point has been handing down 2–3 decisions per sitting, that’s not a recipe for clearing out this backlog anytime soon.

Of course, the Court can (and usually does) add additional hand-down days to its calendar as we approach the summer recess. But with one exception, the Court didn’t start adding those extra dates to its calendar last year until the week of June 15. So it’s possible that, a month from now, the Court will still have 25+ rulings to go, mostly in high-profile, divisive cases—and will have to hustle even more than we’re used to in order to get them all out by July 4.

The Court could also (perish the thought!) allow its calendar to slide into July. But although no statute or rule requires the justices to do so, they have been steadfastly committed to finishing their work by July 1 for decades now—with the only exception being the understandable COVID-caused delay at the end of the October 2019 Term (and even then, the Court wrapped by July 9). I certainly understand why the justices prefer to have a full summer to step back from the most contentious part (and time) of their job, but it’s worth asking at what cost. If this is where we end up this term, with two weeks of wall-to-wall blockbuster rulings squeezed into the last two weeks of June, that would be, in my view, a deeply unfortunate development—regardless of how those rulings come out.

SCOTUS Trivia: July 1974

I’ve mentioned this particular piece of trivia before, but it seemed too closely relevant to today’s Long Read to not re-up. As noted above, the Court slipped past July 4 for its final decisions in argued cases four years ago—when COVID pushed the Court’s last arguments into May, and its last decisions in argued cases all the way to July 9. But the last time that the Court handed down decisions in argued cases later than July 9 was exactly 50 years ago this summer: When the Court not only handed down its unanimous decision in the Watergate tapes case (which was argued only on July 8) on July 24, 1974, but also its deeply divisive 5-4 ruling in Milliken v. Bradley (throwing out a desegregation plan ordered by a federal district court in Detroit) the next (and, as it turns out, last) day—on July 25, 1974.

Curiously, Milliken had been argued in February, so there’s no obvious reason why it took all the way until July 25 to be decided. My best guess is that, given that the Court had granted certiorari before judgment in Nixon on May 31 (and, in the same order, had set that case for oral argument on July 8), the justices knew they had a little more time than usual to resolve their disputes in the Detroit case—and so took the extra time to finish their work.

Imagine that…

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one. This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning. We’ll be back with a regular issue next Monday.

Until then, happy Monday, everyone. I hope that you have a great week!

Steve --- Apart from the numbers themselves, what gets my knickers in a twist, as our British cousins would put it, is the seeming insistence of the majority to arrogantly take a legal "button" (the actual case in front of it) and sew a coat ("rule for the ages") to it. In your recollection, any other Court(s) similarly inclined to "overreach" come to mind ? Also, been meaning to ask (though off topic here) --- from whence does the so-called "public" right to a speedy trial derive ?