75. The Supreme Court's (Formal) Rulemaking Power

Four new proposals from the Supreme Court provide a useful opportunity for a deeper dive into the source of, and debates over, the rulemaking powers that Congress has delegated to the Court

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current work, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

This week’s “Long Read” was spurred by four orders that the Supreme Court handed down last Tuesday—proposing amendments to the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, Bankruptcy Procedure, Civil Procedure, and Evidence. But first, the news:

On the Docket

Once again, given everything swirling around the Court, it was a fairly quiet week. Monday’s Order List came and went without any real news (including any additional grants of certiorari; we’re still at only two thus far for OT2024), and the full Court issued only two orders respecting emergency applications—denying relief with no public dissents in both an Oklahoma death penalty case and the Washington state redistricting case I flagged last week. There were no oral arguments or opinions of the Court. So, like I said, quiet.

This week at least initially augurs more of the same. There was no Conference last week, so no Order List is due later this morning. And the Court has not (yet) announced that it will hand down opinions this week, although this Friday, April 12, is already scheduled as a “Non-Argument Day”— meaning the justices are planning to take the bench. So it wouldn’t be difficult for the Court to add Friday as an opinion day if anything is ready by then; we just don’t have any intel on that yet.

As for pending emergency applications, the Court is still sitting on the Idaho application re: gender-affirming medical care for transgender adolescents, along with the application from military chaplains I described last week (Chief Justice Roberts hasn’t ordered a response to that one, so a denial is likely imminent). There’s also a new application from Missouri death-row inmate Brian Dorsey seeking to block his execution, currently scheduled for tomorrow evening, while the Court considers his claim that Missouri’s flat-fee compensation scheme for public defenders in capital cases violated his constitutional right to the effective assistance of counsel. Presumably, we’ll get some action on that case by COB tomorrow.

Otherwise, the only action the Court took last week was to transmit to the House and the Senate four sets of proposed amendments to federal court rules. And that’s the prompt for this week’s “Long Read.”

The One First “Long Read”: The Supreme Court as Rulemaker

Last Tuesday, the Supreme Court formally transmitted to Congress four sets of proposed amendments to federal court rules—to, respectively, the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure; the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure; the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure; and the Federal Rules of Evidence (there are also Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, but no amendments to those were proposed by the Court last week).

Although none of the amendments in this set of rules appear to be newsworthy for anyone beyond the universe of the practitioners to whom they apply, it struck me as a good opportunity to introduce those less familiar with it to the Court’s formal rulemaking power—and to flag some of the questions that it continues to raise.

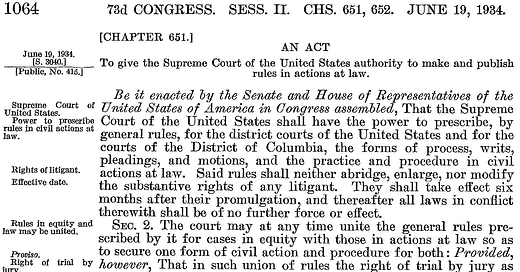

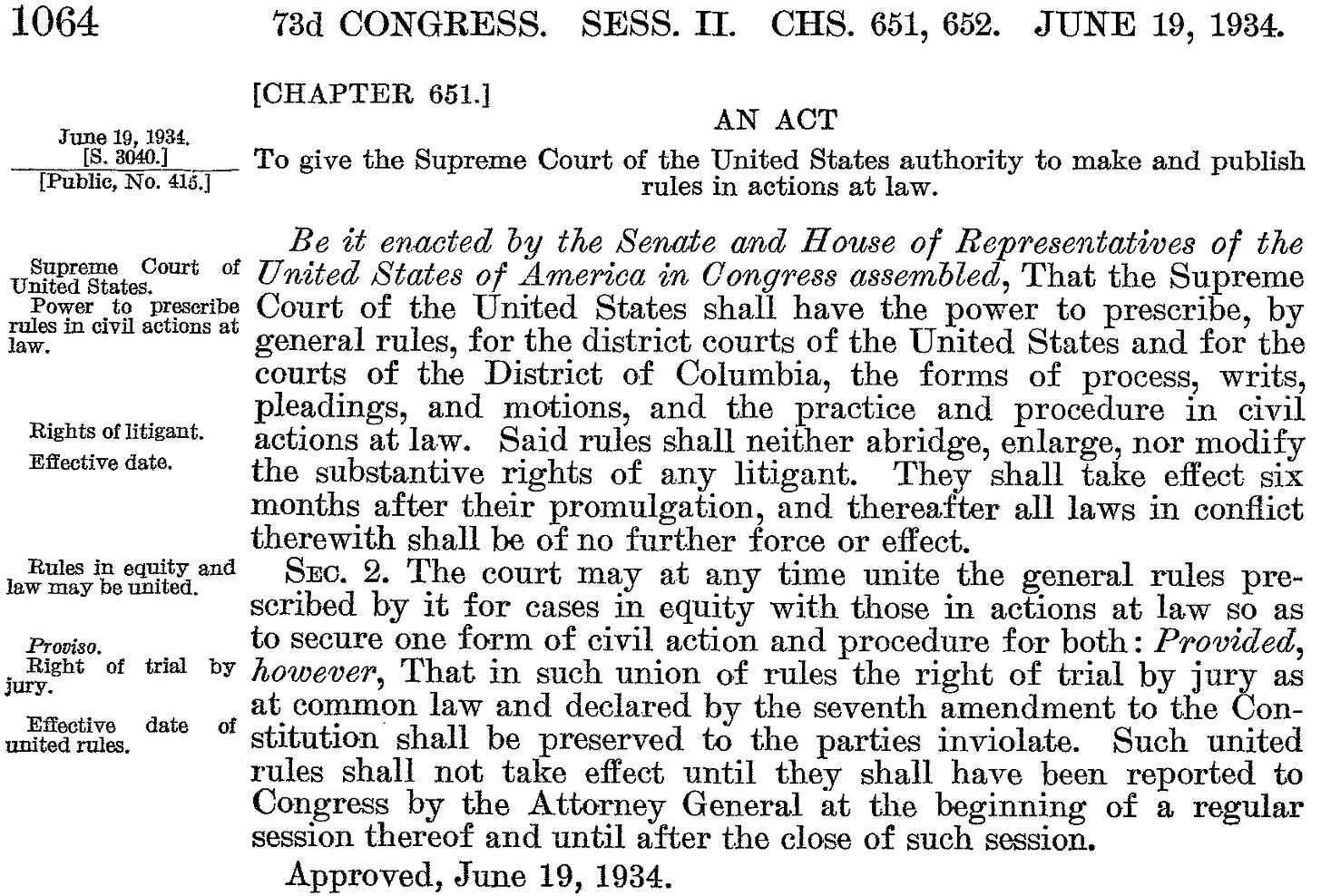

The Court’s formal rulemaking power comes from a statute known as the Rules Enabling Act, first adopted in 1934, but amended a number of times, including in some especially significant respects in 1988. Part of a massive effort in the early 1930s to create more uniformity in federal courts (including through the “merger” of law and equity, i.e., the effort to have a single set of procedural rules regardless of the specific type of relief litigants sought), the Rules Enabling Act had three major goals: First, to clarify that federal courts can make their own rules, so long as those rules don’t “abridge, modify, or enlarge any substantive right.” Second, to formalize the process by which those rules would be adopted and amended. And third, by doing so, to standardize, as much as possible, practice across the federal courts.

The centerpiece of the 1988 reforms was to standardize not just the process by which rules are formally proposed and adopted, but also the process prior to that point. After and under the 1988 reforms, there are basically seven steps to how a new rule (or an amendment to an existing rule) comes into effect:

Initial Consideration by the “Advisory Committee”: One of the reforms in the 1988 act was the standing up of formal “Advisory Committees” for each of the five sets of external rules administered by the Supreme Court (the Court also has its own rules, but those go through a different process). Each Advisory Committee includes federal and state judges, practicing lawyers both from the private sector and the Department of Justice, and academic experts. And each committee has a “reporter,” usually a well-established law professor in the field, who is responsible for coordinating the committee’s agenda and drafting appropriate amendments to the rules and explanatory committee notes. It’s the reporter who, after receiving suggestions from others (or with suggestions of their own), will make appropriate recommendations to the Advisory Committee, including proposed language for potential rule changes.

Publication and Comment: Once one of the Advisory Committees votes to adopt an amendment, it must receive approval from the Judicial Conference’s “Standing Committee”—the Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure of the Judicial Conference (i.e., a bunch of federal judges). Once the Standing Committee approves, the proposed amendment is published and distributed far and wide, and the Advisory Committee usually holds at least one public hearing during the period it provides for public comment (usually six months).

Final Advisory Committee Approval: Once the public comment period has ended, the reporter prepares a summary of the public comments and testimony, and makes a final recommendation to the Advisory Committee. If the Advisory Committee approves the amendment, it submits a report to the Standing Committee—including the relevant public comments, and, if any members of the Advisory Committee wish to file a dissenting statement, that, as well.

Final Standing Committee Approval: The Standing Committee then conducts its own assessment of the proposal. It can accept, reject, or modify the Advisory Committee’s recommendation, If it accepts the recommendation, the amendment goes to the full Judicial Conference (the 26 judges I discussed in this prior issue).

Judicial Conference Approval: The Judicial Conference typically reviews proposed amendments to the rules at its annual September meeting. If it approves proposed amendments, they are transmitted promptly to the Supreme Court.

Supreme Court Approval: The justices then vote up or down on the proposal as submitted by the Judicial Conference. It is not unheard of for justices to file public statements respecting the Court’s approval of proposed amendments, especially if they disagree. By statute, if the Court wants a proposed amendment to go into force during a calendar year, it must submit the amendment to Congress no later than May 1 (hence the public approvals and transmissions to Congress last week, in plenty of time for the May 1 deadline).

Congressional Inaction: Finally, the Rules Enabling Act gives Congress no less than seven months to disapprove any amendments to the rules. If Congress does not enact legislation to reject, modify, or defer the proposed amendments, then they take effect as a matter of law on December 1 of the year in which they were proposed. That’s where we’re headed with the four sets of amendments the Court transmitted to Congress last Tuesday. (Most famously, Congress disapproved of the entire Federal Rules of Evidence when they were proposed in 1973—and only adopted them as a statute, with some significant changes and limits on when they can be amended through the rulemaking process, in 1975.)

If all of this sounds quite … involved, it is—by design. Amending the rules is intended to be a slow, drawn-out process, where there are plenty of opportunities for interested stakeholders to weigh in (and, if necessary, publicly object). That said, there are, still today, at least three sets of ongoing issues about the Supreme Court’s power under the Rules Enabling Act that ought to be flagged:

I. The Court’s Inability to Clearly Draw the Substance/Procedure Line

As noted above, perhaps the central limitation in the Court’s rulemaking power under the Rules Enabling Act is that no rule may “abridge, modify, or enlarge a substantive right.” But where, exactly, is the line between procedural rules and substantive rules? As first-year law students learn (usually to their horror) in Civil Procedure, the Supreme Court has not always done a good job of answering that question—which is especially significant in “diversity” cases (suits arising under state law), in which federal courts are supposed to apply state substantive law and federal procedural rules. Ever since Hanna v. Plumer, the Supreme Court’s assumption has been that, if a Federal Rule of Civil Procedure is “valid” (that is, if it doesn’t exceed the Court’s authority under the Rules Enabling Act), then it’s “procedural.” But that test just changes the words for asking what is, in essence, the same question. To get a feel for how unable the Court has been to articulate exactly where its rulemaking power leaves off, consider its 2010 decision in the Shady Grove case, in which Justice Scalia couldn’t muster a majority for when a federal rule should be able to displace a state law, and the dissenters (who believed it didn’t in that case) included Justices Ginsburg, Kennedy, Breyer, and Alito. More than just headache-inducing for Civil Procedure students, the blurriness of the line also has implications for the Court’s ability, acting without Congress’s specific permission, to do everything from displace contrary state laws in civil cases to, as Rule 42(a) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure does, authorize appointments of private attorneys to try criminal contempt-of-court offenses that the Justice Department declines to prosecute.

II. The Potential for Conflict Between the Court’s Distinct Functions

A related but distinct issue arising under the Rules Enabling Act is the potential for conflict between the justices’ two roles. In a lawsuit in which the validity of a rule proposed by the Supreme Court under the Rules Enabling Act is challenged, what weight should courts give to the fact that the Supreme Court already approved the rule, albeit in its rulemaking—not adjudicatory—capacity? Obviously, lower courts aren’t formally bound by the Court’s role in the rule’s adoption. But should lower courts treat the Court’s transmission of a rule proposed by the Advisory Committee as an endorsement of its validity to which they owe at least some deference?

The Court has never really weighed in on this issue—although its decisions in cases like Shady Grove have, unsurprisingly, not treated its prior approval as in any way preclusive. But at bottom, this issue largely dovetails with the related debate over whether the Court’s job in reviewing amendments proposed by the Advisory Committee is itself supposed to be deferential, or is more akin to de novo review. On this point, the justices have themselves long differed—as then-Professor (now-Judge) Karen Nelson Moore pointed out in a helpful 1993 law review article on the subject.

III. The Rules Enabling Act’s Push Toward Rulemaking Over Common Law

Finally, there’s also a recurring question about whether/when the Court’s formal power to propose procedural rules should preclude exercises of common law powers to do the same (that is, procedural rulemaking through judicial decisions). A good example comes in the context of the “collateral order doctrine,” a series of cases dating back to 1949 in which the Court has recognized limited circumstances in which pre-trial orders that are not usually subject to immediate interlocutory appeal can nevertheless be brought promptly to a court of appeals (on the ground that the pre-trial order is, at least on that specific issue, effectively final). Although the Court had, for a time, expanded the doctrine through case law, amendments to the Rules Enabling Act in 1990 and 1992 specifically empowered the Court to clarify by rule when otherwise un-appealable interlocutory district court rulings could be appealed. The Court has since relied upon those amendments to justify not expanding the collateral order doctrine through judicial decisions. But Congress’s specificity in the contexts of interlocutory appeals raises the question of whether, more generally, the Rules Enabling Act should be understood to disfavor judicial innovation through decisional law in contexts in which the same principle could validly be espoused through a properly promulgated rule. Again, the Supreme Court has never really weighed in on the matter.

In the grand scheme of things, quibbling over the limits of the Court’s power under the Rules Enabling Act may seem like small potatoes compared to everything else that’s going on. Fair enough. But the Court’s formal rulemaking power is yet another example of the authority that Congress has chosen to delegate to the Court over the years—one that exists largely out of sight, but that perhaps shouldn’t be entirely out of mind.

SCOTUS Trivia: Old Supreme Court Rules

Although I have been (and remain) critical of some of the … less-transparent … features of the Supreme Court’s website, it’s also worth singing the praises of some of the very cool resources it does provide. One of them is a link to digital scans of old versions of the Supreme Court’s rules—dating all the way back to 1803!!

There’s a whole lot of stuff in there that folks could truly nerd-out on. I’ll just say kudos to the Court’s staff for making these available.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one. This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning. And we’ll be back with a regular issue next Monday.

Until then, happy Monday, everyone! I hope that you have a great week!