73. The Supreme Court and State Courts

From the beginning, the Supreme Court has had a different relationship with state courts than with lower federal courts, with relevant takeaways for our modern understanding of the Court's role

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current work, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

After three issues last week focused on current events, I thought I’d use today’s installment, after recapping the news, for a bit of a step-back look at a shrinking part of the Court’s docket: review of state court decisions.

On the Docket

Obviously, the biggest news of the week was the Court’s non-intervention in the SB4 case, part (but not the end) of a whiplash-inducing timeline that I summarized in detail in a special extra issue last Wednesday, before a longer reflection on Justice Barrett’s … enigmatic … concurrence in Thursday’s bonus issue. As of now, SB4 remains on hold, whether because the Fifth Circuit panel hearing Texas’s appeal hasn’t yet ruled on Texas’s motion for a stay pending appeal, or because it intends to wait for the oral argument on the merits, which is still on for next Wednesday (April 3) in New Orleans.

The only other orders out of the full Court last week were two denials of emergency relief (over no public dissents) to Georgia death-row inmate Willie Pye, who was executed on Wednesday. Chief Justice Roberts, in a rare “in-chambers opinion” (a writing accompanying a circuit justice’s solo order), denied emergency relief to Peter Navarro—who had sought to be kept out on bail while he appeals his conviction for contempt of Congress. It was the first in-chambers opinion since 2014(!).

In addition to the Court’s relatively quiet Order List last Monday, the only other big headline was the Court’s inaction in Labrador v. Poe, Idaho’s long-pending emergency application asking the justices to put back into effect its ban on gender-affirming medical care for transgender adolescents. At this point (more than three weeks after briefing was completed), it seems possible that the Court might just be sitting on the application until it’s in a position to grant plenary review of one of the other cases in which a comparable state-law ban has been challenged. (The three consolidated petitions in the Tennessee case had been set for Conference last Friday, but were “rescheduled” on Wednesday.)

We expect a regular Order List today at 9:30 ET, followed by the second week of the March argument session—including tomorrow’s much-anticipated argument in the mifepristone case. As of now, no opinions are expected this week, but that, as always, can change. There’s also a new emergency application from the appellants in Alexander—the South Carolina racial gerrymandering case in which the Court heard oral argument in October—asking the justices to put one of South Carolina’s contested congressional maps back into effect so that it can be used during the 2024 election cycle. Chief Justice Roberts, in his capacity as Circuit Justice for the Fourth Circuit, ordered a response to that application—which is due later today.

The One First Long Read: State Courts at SCOTUS

When the Supreme Court decided McElrath v. Georgia a few weeks ago, Justice Jackson included a standard-seeming phrase as the last sentence of her opinion for the Court: “the case is remanded for further proceedings not inconsistent with this opinion.” But most decisions from the Court that return a case to the lower courts end with a slightly different formulation; Justice Sotomayor’s opinion in Wilkinson v. Garland, for instance, concluded by noting that the Court “remands the case for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.” This difference is not a reflection of the justices’ different styles; it reflects the courts to which the cases are being remanded. The latter (“consistent with”) phraseology is the directive the Court issues to lower federal courts; the former (“not inconsistent with”) is what goes back to state courts. And although this might seem like a semantic distinction, it reflects a far more significant difference in the Supreme Court’s role with respect to these two different sets of lower courts—a difference that goes all the way back to the Founding, but which we’ve largely forgotten lately.

Today, and (with some small exceptions) since the Judiciary Act of 1925, the Supreme Court has jurisdiction to review an overwhelming majority of decisions by the lower federal courts—including any decision by a federal court of appeals, regardless of the subject-matter of the dispute; the diversity of the parties (i.e., whether they’re from the same state or not); or the procedural stage of the litigation. But the Court’s review of state courts is, and always has been, far more circumscribed—in three different respects that persist today, and at least one more major respect historically.

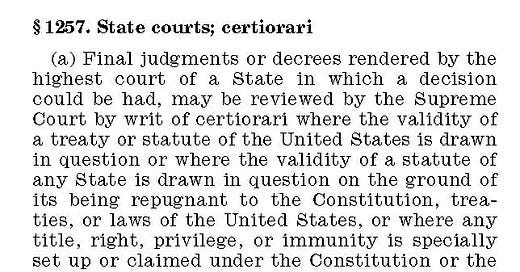

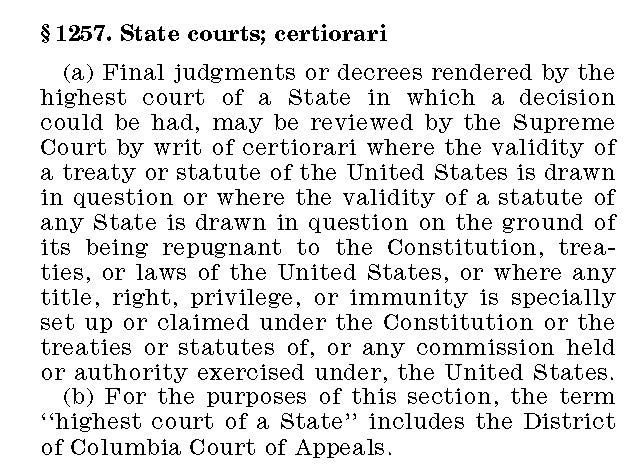

First, and most significantly, the Supreme Court is empowered to review only those state court decisions that turn, in some respect, on a question of federal law. Although the Constitution would allow broader appellate jurisdiction (e.g., in cases turning on state law, but between citizens of different states), the Court since 1875 has interpreted 28 U.S.C. § 1257 (the present-day codification of section 25 of the Judiciary Act of 1789) far more narrowly. Specifically, if the state court ruling rests on an “adequate and independent state ground,” then the Supreme Court can’t review it, no matter how significant a question of federal law might also be involved. “Independent,” in this context, means a state law that is interpreted on its own, and not by reference to some parallel federal law. And “adequate” means a rule that the state courts regularly follow (versus one that was made up for the case at hand).

The basic idea here is that, because the Supreme Court would be bound in such cases by the Rules of Decision Act to apply state law as interpreted by the state’s highest court, there’s little point in giving the justices power to review lower-court rulings in which their review would be limited to endorsing what the lower court did. By volume, though, this is the single biggest difference between Supreme Court review of state courts and lower federal courts; thanks to the “adequate and independent state ground doctrine,” the overwhelming majority of state court decisions are not within the statutory appellate jurisdiction of the U.S. Supreme Court, and never have been.

Second, the statute also limits the Supreme Court to review of “final judgments or decrees,” whereas the Court’s review of federal courts of appeals runs to any case “in” the court of appeals. To be sure, the Court has long taken a “pragmatic” approach to “finality” in this context: The question typically reduces to whether the federal issue that forms the basis for the Court’s review has been conclusively resolved by the state court, even if further litigation of state-law issues might remain. But this is still another significant way in which the justices’ power to review state courts is more circumscribed than their corresponding power over (most) lower federal courts.

Third, § 1257 also limits the Court to reviewing decisions of “the highest court of a State in which a decision could be had.” Again, the Court has taken a more functional approach to this language—so that it can review lower state courts in contexts in which the state’s highest court denied discretionary review or lacked jurisdiction. But again, unlike its ability to directly review federal district courts in several contexts, the Supreme Court generally lacks the power to directly review lower state courts.

All of these constraints are still very much part of the Supreme Court’s understanding of its docket. And they have numerous effects—including complicating the circumstances in which the Court can issue emergency relief with respect to lower state-court decisions; making it more likely that a particular cert. petition might present jurisdictional issues (e.g., if there’s some debate about finality, or the existence of an adequate and independent state ground, etc.).

But perhaps the most striking historical limit on the Supreme Court’s appellate jurisdiction over state courts is one that lasted for the first 125 years of the Republic before Congress eliminated it: Under the Judiciary Act of 1789, and until the Judiciary Act of 1914, the Supreme Court lacked the power to review any state court decision in which a claim of federal right was upheld. Thus, if state courts sustained a federal challenge to a state law, or allowed parties to enforce a federal statute over a contrary state law, that would be the last word, at least within that state, on the meaning of that federal law. Nor was this an oversight; as Justice Stevens pointed out in his dissenting opinion in Michigan v. Long, the general presumption animating that part of the Judiciary Act of 1789 was that state courts should be free to vindicate (if not even over-protect) federal rights.

Congress shifted course in 1914 at least partly in reaction to an especially visible state-court ruling: The New York Court of Appeals’ 1911 ruling in Ives v. South Buffalo Railway, in which the court, relying upon the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, struck down the first workers’ compensation law in the country. At the time, that ruling couldn’t be reviewed at all by the Supreme Court. The 1914 Act gave the justices the power to review such decisions by certiorari—a power they retain today.

It’s quite remarkable, in my view, to consider that Congress, for 125 years, saw no problem with state courts having the last word on questions of federal law—so long as they were siding with federal law at the expense of state law. Among lots of other things, it’s a telling reflection not just of the extent to which Congress was not worried about the Supreme Court’s ability to have the last word in such cases, but also of how Congress, at least when it initially set out the Supreme Court’s appellate powers, was focused more on cases in which the Court was needed to vindicate federal rights than those in which the federal judicial interest was in ensuring uniformity of federal law across the courts of different states.

That understanding may seem quite foreign today, but it sure seems relevant to a host of contemporary conversations that those who drafted and enacted the Judiciary Act of 1789 saw the vindication of federal law as the dominant jurisdictional interest.

SCOTUS Trivia: State Supreme Court Justices on SCOTUS

State courts were, for obvious reasons, a common place from which justices were appointed in the early years of the country and for much of the nineteenth century. But state supreme court experience, much like experience in the legislative branch of government, has increasingly become a rarity among the justices. Of the 59 justices confirmed to the Court since the turn of the twentieth century, only six had state supreme court experience: Justice Holmes (Massachusetts); Justice Joseph Lamar (Georgia); Justice Pitney (New Jersey); Justice Cardozo (New York); Justice Brennan (New Jersey); and Justice Souter (New Hampshire). Justice O’Connor, who served on both the trial and intermediate appeals courts in Arizona, never served on the state’s highest court.

In other words, since Justice Brennan’s appointment in 1956, only one of the 26 justices to be appointed to the Court had prior state supreme court experience; and only two had state court experience of any kind.

Maybe that’s an additional explanation for why, of the 58 cases the Supreme Court decided through signed opinions during the October 2022 Term, only one was a direct appeal from a state court…

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one. This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning. And we’ll be back with a regular issue next Monday.

Until then, happy Monday, everyone! I hope that you have a great week, even if your brackets don’t.

The Supreme Court would greatly benefit from the appointment of justices with state court and legislative experience. It would also benefit from the appointment of more justices with extensive experience as litigators in trial, as well as appellate courts. (That experience was invaluable in shaping the perspective of Justice Stevens.)

A court whose justices reflects a wide range of legal backgrounds and practice would be far better equipped to appreciate the effects of its decisions. That would lead to better opinions and more fair results.

Great read. The procedural mechanics of lawmaking, writs and stays, have always struck me as equally if not more relevant than the substantive outcome of cases. The power to decide which cases matter is the only power that matters, and it remains firmly limited to those selected through naked corruption or malfeasance, who then behave corruptly, both in their personal lives and in their jurisprudence. John Locke's nondelegation doctrine does not say what Gorsuch wants it to say. There is no individual right to bear arms etc., to say nothing of the fact that the Constitution should not be treated as the legal equivalent of a grocery-store checklist.