70. The Shoddy Politics of Trump v. Anderson

The Section 3 disqualification case provided the Supreme Court with a chance to engage in true constitutional statesmanship. The five justices in the majority ... didn't.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us. A special welcome to all of our new subscribers!

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current work, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

Obviously, last week’s biggest headline was Monday’s ruling in the Colorado ballot disqualification case, Trump v. Anderson, which is discussed in far more detail below. Consider this your not-so-subtle encouragement to keep reading.

The Court also scheduled oral argument in the Trump immunity case by adding one more day to the April calendar—with Trump v. United States closing out the term’s arguments on Thursday, April 25. And an otherwise quiet order list included a rare three-way split in Speech Now v. Sands—a First Amendment challenge to Virginia Tech’s “bias intervention and response team” policy. The majority issued a “Munsingwear” vacatur—summarily granting certiorari, vacating the decision below, and remanding with instructions to dismiss the case as moot. Justice Jackson reiterated her continuing objections to what, in her (and my) view, is a problematic use of Munsingwear (she would’ve just denied certiorari). And Justice Thomas, joined by Justice Alito, would have granted certiorari and conducted plenary review—as he explained in a six-page dissent. Other than the State of the Union, that was it.

No orders are expected at 9:30 today (there was no Conference last week); no oral arguments are scheduled until next Monday; and the Court has not indicated that any opinions in argued cases are expected this week. That said, there are now four major emergency applications, covering three disputes, pending before the Court—one of which is already ripe, and the other three of which will become ripe for decision later this week.

First, I’ve written before about Labrador v. Poe, in which Idaho is asking the Court to put back into effect its ban on gender-affirming medical care for transgender adolescents. Briefing on that application has been complete for over a week (since March 1). My best bet is that there’s a denial with some writing coming, but that prediction is worth what you paid for it.

Second, as I predicted last week, the Court now has before it two emergency applications asking it to keep from going into effect a new Texas law (“SB4”) that effectively creates a state-level deportation regime. On February 29, a district court issued a preliminary injunction preventing the law from going into effect. But the Fifth Circuit responded with an open-ended “administrative” stay of the injunction, which it then paused for seven days. That stay would have expired (and SB4 would’ve gone into effect) on Saturday, but last Monday, Justice Alito issued administrative stays of his own—keeping the Texas law on hold until 5 p.m. (EDT) this Wednesday, March 13. Alito can always extend that deadline, but it seems likely that we’ll hear from the Court on these applications sometime this week.

Finally, and speaking of Texas, the Court also received an application seeking an order blocking West Texas A&M’s campus ban on drag shows on the ground that it violates the First Amendment. Justice Alito called for a response to that application by 5 p.m. (EDT) this Wednesday, so it’s also possible that the justices rule on this application this week, too. Even if no other emergency applications further consume the Court’s resources between now and next Monday, the approaching March argument session (which has some blockbusters all its own) is its own compelling incentive for the justices to clear their decks.

The One First “Long Read”: The Mess the Court Made

As folks who have read either last week’s issue of this newsletter or my earlier discussion of the ballot disqualification case know, I am not one of those who thought that the Court would (or even should) affirm the Colorado Supreme Court’s ruling that former President Trump is disqualified from holding future office under Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment. I won’t rehash those posts here other than to note that my principal arguments have always been political, not legal—that this was a context in which the Court would (and should) approach the dispute with appreciation not just for the constitutional text, but for the high constitutional politics of allowing individual states to do what Colorado had done. In other words, my assessment of Monday’s ruling comes as someone who expected, even before the oral argument made this outcome entirely foreordained, for the Court to duck the plain text and historical purpose of Section 3 in favor of present-day constitutional politics.

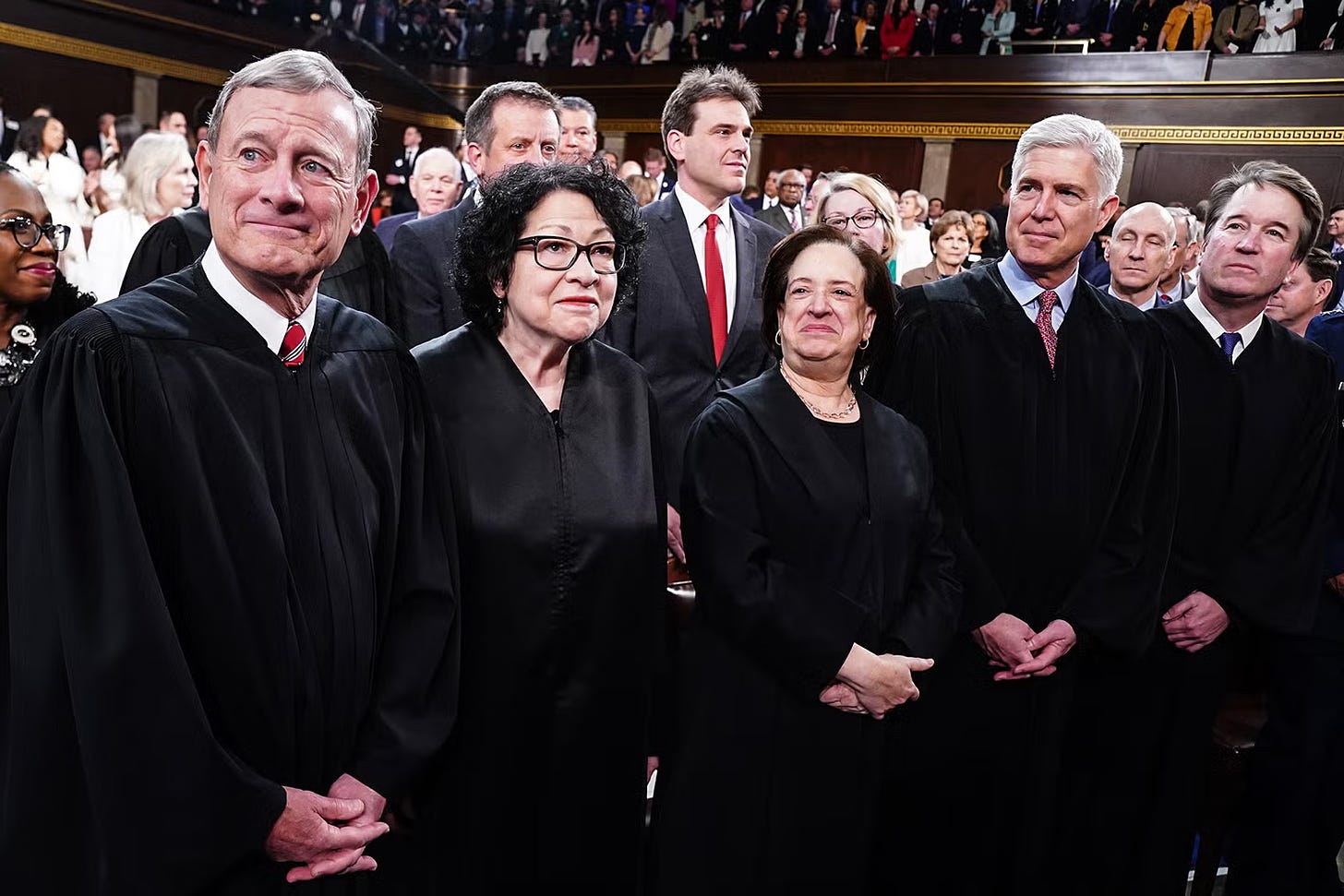

It’s against that backdrop that I’m especially exasperated by what the Court actually did. It is abundantly clear, from both the joint opinion concurring in the judgment (from Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson) and from the brief partial concurrence from Justice Barrett, that there were nine votes for the narrow proposition that states cannot unilaterally disqualify presidential candidates under Section 3. Such a short, narrow ruling would not have satisfied those focused on pure legal analysis, but, again, they were never going to be satisfied.

As Justice Barrett noted, the Court could—and should—have stopped there. And yet, for reasons that their unsigned opinion never adequately explains, the five justices in the majority went some distance further—clearly holding that states can’t use Section 3 to disqualify congressional candidates, either; and at least seeming to suggest that, even at the federal level, the only obvious way to enforce Section 3 is through enabling legislation enacted by Congress.

There’s debate as to whether this last point is or is not a fair reading of the majority opinion; it is certainly what the joint concurrence claims the per curiam opinion does, although perhaps that’s because an earlier draft was even clearer, and the final version was watered down in response to the concurrence’s complaints. Either way, this mess leaves three massive problems with what the Court did even from a high politics standpoint—at least two of which could have been easily avoided, and one of which, well, was always going to be a problem.

First, when I think of the Court’s leading “political” decisions across its history—cases in which the justices were clearly focused on high institutional politics/constitutional statesmanship, and the legal analysis was, at best, an afterthought—the ones we hold in the highest acclaim were all unanimous not just as to the result, but as to the rationale. Brown was unanimous, with no separate opinions. Ditto Loving. Ditto the Watergate tapes case. Cooper v. Aaron went even further—with every justice signing their name to the opinion of the Court. We know that the justices didn’t all agree with every word that the Court wrote in each of these cases, but speaking in one voice was a central part of the political enterprise; these rulings were about the Court as an institution, not the justices as individuals.

In contrast, some of the Court’s most controversial decisions have involved overtly political rulings that failed to produce unanimous rationales—like Dred Scott and Bush v. Gore, just to name two. The reason for this distinction is simple enough: it is easiest to accept a decision on terms of high institutional politics when the Court speaks as an institution. When it’s just a subset of the justices, the decision looks less like the Court is engaging in judicial statesmanship—and more like it’s just dressing up more ordinary disagreements in institutional clothing. And although a unanimous rationale was never going to be in the cards in Dred Scott and Bush v. Gore, it clearly was a possibility here, per Justice Barrett’s concurrence. For five justices to knowingly embrace a majority rationale that ended up depriving the Court of the ability to speak in one voice is, I fear, a self-inflicted wound.

Second, and related, a decision that is so overtly political should, at the very least, be clear as to what it does (and doesn’t) settle. In this regard, although one of the per curiam opinion’s two unnecessary holdings is clear enough (that states can’t unilaterally disqualify any candidates for federal office under Section 3), the opinion is distressingly ambiguous about the other unnecessary holding—how federal officials can enforce Section 3 in future cases. All nine justices agree that Congress can pass implementing legislation under Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. But can Congress enforce Section 3 when it counts (or objects to) presidential electors during the January 6 Joint Session prescribed by the Electoral Count Act of 1887? Can federal courts enforce Section 3 in lawsuits challenging current actions taken by allegedly disqualified federal officers? As the flood of commentary on the ruling over the past week makes clear, there are plausible readings of the majority opinion that go in both directions on this question. But what the heck was the point of going past the ground on which the justices were united (and, thus, sacrificing the Court’s ability to speak in one voice) if it wasn’t to be clear about what is and is not permissible going forward?

My best bet is that an earlier draft was clearer (and went further), and was toned down in response to Justice Sotomayor’s draft dissentconcurrence. Even then, though, the majority’s response should either have been to not reach those issues in the first place, or to decide them unambiguously. To get stuck in the middle is, in many respects, worse than either of those alternatives.

Third, and going back to last week’s discussion of the Court’s inconsistent role morality, the lack of both unanimity and clarity as to the precise forward-looking enforceability of Section 3 comes across as especially galling from this Court. As I wrote (at … length), part of the issue is the depleted capital with which the justices entered the decisionmaking process in this case. Had the votes come out the same but not aligned so ideologically, maybe it would hit different. But for these five justices to muck up the easy path to a clean, unanimous decision without any real defense does very little to buy the Court more credibility coming out of this case. I’ve used this line before, but I’m reminded, again, of Michael Sheen’s Tony Blair in The Queen: “Won’t someone save these people from themselves?”

I’ve taken a lot of (understandable) flak for my views on this case, and for my efforts to defend the Court’s procedural behavior, to this point, in the immunity case (which is now set for oral argument on April 25). I suspect I’m never going to convince those who have lost faith in the Court that there are principled justifications for the justices’ actions, even if we might disagree with those principles and/or their application. But at some point, if the Court wants to persuade anyone who isn’t already persuaded that its actions are reflecting such principles, it needs to do more to act like it. At least for me (if not for you), Trump v. Anderson was an easy opportunity for the Court to score some points for high statesmanship. For reasons that are not yet apparent, and may never be, it failed.

SCOTUS Trivia: Justice Rutledge’s Non-Vote in Hirota

The discussion of unanimity reminds me of one of the stranger things I’ve encountered in my research—Justice Wiley Rutledge’s refusal to vote, up or down, in Hirota v. MacArthur.

I’ve written about Hirota—in which the Court held that it lacked jurisdiction to entertain “original” habeas petitions from Class A defendants convicted by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East—before. The case had a number of quirks—including Justice Douglas taking six months to file a (belated) concurrence that reads much more like a dissent. But perhaps the strangest feature of the case is the non-vote of Justice Rutledge, who participated in the argument and Conference, and who may have helped to precipitate the Court taking up the case in the first place. When the Court handed down its brief, unsigned ruling on Monday, December 20, 1948 (just three days after the conclusion of oral argument), the order noted that Rutledge “reserves decision and the announcement of his vote until a later time.” Rutledge died the following September—having never voted, one way or the other, on the disposition in Hirota.1

There may be other non-recusal abstentions in the U.S. Reports, but none with which I’m familiar.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one. This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning. And we’ll be back with a regular issue next Monday.

Until then, happy Monday, everyone! I hope that you have a great week.

Justice Douglas’s archival papers include an April 1950 letter from Walter Wyatt, the Reporter of Decisions, to Douglas, noting that he had “discussed the matter with Mr. Justice Rutledge shortly after the Fourth of July last year [1949]; and he told me that he had not yet made up his mind how he would vote in this case.”

Speaking of the lack of judicial statesmanship, in the insurrection case of Trump v. United States, the Court should have denied the petition for certiorari filed by the Special Counsel in order to let the excellent and comprehensive discussion of the issue by the D.C. Circuit Court remain the final word on Trump's claim of absolute and total immunity. The Court further de-legitimized itself by granting certiorari when everyone knows the Court will not agree with Trump that he was elected as the invincible king. The grant of certiorari was a political act to aid Trump in delaying the criminal trial and jury verdict until after the election.

" For reasons that are not yet apparent, and may never be, it failed."

I think the reasons are apparent. Alito and Thomas are convinced of their own righteousness and don't feel a need to back off to preserve the credibility of the institution. They have the power, lifetime tenure, and certainty of their own rightness, so why compromise.