66. United States v. Trump

Later today, former President Trump will ask the Supreme Court to freeze the criminal prosecution against him arising out of January 6. Here's a rundown of how we got here—and what happens next.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us. And a very special welcome to our new subscribers; last week saw our biggest influx since we launched in November 2022.

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

The big news last week was, of course, Thursday’s oral argument in Trump v. Anderson—on whether former President Trump’s conduct before and on January 6, 2021 disqualified him from holding future office under Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment. You’ve probably read plenty of commentary on the argument already; I’ll just say that there’s a reason why almost all of it has gravitated toward the expectations that (1) the Court will reverse the Colorado Supreme Court—and hand down a very narrow opinion holding that states, on their own, can’t disqualify presidential candidates under Section 3; (2) such a ruling will likely be either unanimous or close to it; and (3) the Court will avoid all of the harder questions the case raises. (And that all of this will likely happen in relatively short order.) My “things I’ll be listening for” post from Thursday morning held up pretty well…

There will be plenty more to say about this result once we actually get it. For now, I’ll just flag an op-ed that I wrote for CNN on Thursday afternoon about how ironic it is that this Court, all of a sudden, is so fixated on the potential consequences of its rulings as a factor to consider in reaching its disposition. Some of us have always thought that high politics are part of what the Court does; it would sure be useful for the justices to admit it in a case in which it’s so visible.

Understandably buried in the headlines coming out of Thursday’s argument were the two decisions the Court handed down right before the argument on Thursday morning—the second and third in cases argued so far this term (yes, it’s way behind):

In Department of Agriculture v. Kirtz, Justice Gorsuch held, for a unanimous Court, that the Fair Credit Reporting Act does waive the federal government’s sovereign immunity—meaning that plaintiffs can enforce the Act not just against private lenders, but against the federal government if and when the government supplies false information that affects a plaintiff’s credit. (Unlike congressional waivers of state sovereign immunity, which raise a hornet’s nest of constitutional questions, waivers of federal sovereign immunity are perfectly fine—so long as they are clear, as the Court held that this one is.)

And in Murray v. UBS Securities, LLC, Justice Sotomayor held, also for a unanimous Court, that, to state a valid retaliation claim under the whistleblower protections of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, a plaintiff does not have to show that the employer acted with “retaliatory intent”; she need show only that her protected activity (usually, the whistleblowing) “was a contributing factor in the employer’s unfavorable personnel action.” In other words, the decision makes it a bit easier for whistleblowers to challenge subsequent personnel actions taken by their employers. Justice Alito filed a brief concurring opinion, joined by Justice Barrett, principally to suggest that there’s not that much daylight between the two standards. We’ll have to see if lower courts agree.

Turning to this week, the Court has nothing formal on its calendar until the justices’ Conference on Friday—their first formal confab since January 19 (the regular February argument session begins next Tuesday). But last Friday, the Court docketed an emergency application seeking to freeze the bankruptcy plan for the Boy Scouts of America on the ground that the releases of third-party claims in the plan raise similar issues to those currently before the Court in the Purdue Pharma case (which was argued on December 4). Of course, the justices already know how they’re coming out in that case. So the disposition of the application in the Boy Scouts case could be a telling clue.

And, as explained below, later today, we expect that former President Trump will file an emergency application to stay the mandate from last Tuesday’s D.C. Circuit ruling—in which a three-judge panel rejected Trump’s claim of immunity from criminal prosecution for his role in the events leading up to and on January 6, 2021. Although there’s no Supreme Court deadline requiring Trump to file today, if he doesn’t, the D.C. Circuit’s mandate will issue—which would clear the way for Judge Chutkan to proceed in the trial court. I expect Chief Justice Roberts (in his capacity as Circuit Justice for the D.C. Circuit) to call for a response to the application pretty quickly, and to have it due this week, perhaps as early as 5 p.m. on Wednesday. So there’s a chance we hear from the Court on whether the January 6 prosecution can go forward by the end of this week, although my money is on next week.

The One First “Long Read”: Trump and the Court, Redux

The Colorado ballot disqualification case and the January 6 prosecution raise distinct legal issues. Nevertheless, it’s hard not to see them as being at least loosely related—since both are, at their core, about different modes of accountability for former President Trump’s role in and responsibility for what happened on January 6. And because of the timing not just of the D.C. Circuit’s ruling last Tuesday, but of how the court of appeals structured the mandate, the justices now have a chance to resolve them, if not simultaneously, then at least at roughly the same time. To understand why, it’s worth carefully walking through what happened and what’s about to happen:

I. What Happened Last Week?

Here’s the easy part: Last Tuesday, a unanimous (and, it’s worth stressing, ideologically diverse) panel of the D.C. Circuit issued a 57-page opinion emphatically rejecting former President Trump’s claim that the Constitution immunizes him from criminal prosecution for any and all acts taken while he was President. The opinion is worth reading in full; I’ll just flag that I agree with just about all of it (along the lines of this newsletter entry from last August). And critically for present purposes, I suspect that at least six justices (and perhaps eight or nine) agree with it, too.

Normally, a criminal defendant would have 14 days to ask for rehearing en banc (there was some confusion about this online from folks who apparently don’t know that the rules are different in criminal cases). And then they’d have at least 90 days, extendable to 150 days, to file a cert. petition seeking further review from the Supreme Court. But the D.C. Circuit panel took steps to speed up that clock. Here’s the one-page judgment order accompanying the opinion (nerd alert: it’s actually the judgment order that matters; the opinion is just the explanation for the order):

II. Why/What Does Trump Have to File Today?

That long paragraph is the part that matters. The reason why the January 6 trial is currently blocked is because of a stay issued by the trial judge, Judge Chutkan, pending Trump’s appeal to the D.C. Circuit of her ruling denying his immunity-based motion to dismiss. That stay expires (and proceedings can resume in the trial court) as soon as the D.C. Circuit’s “mandate” issues. And in its judgment order, the three-judge panel provided that its mandate will issue tomorrow (the day after February 12) unless Trump files an application for a stay with the Supreme Court today. If he does that, then the mandate will remain frozen until the Supreme Court acts on the application, one way or the other. (More on the Court’s options below.)

In other words, for Trump to keep the trial on hold, he must apply to the Supreme Court for a stay by the end of today. He could still theoretically seek rehearing from the full D.C. Circuit, but the panel’s order specifically provides that such a petition won’t pause the mandate; that’ll happen only if the full D.C. Circuit grants rehearing (which it won’t; there’s no way to get to a majority of the D.C. Circuit without at least one of the judges on the Trump panel). It’s a clever move by the panel—to preserve all of Trump’s appellate rights, but to impose real consequences for any delay.

That’s why everyone expects Trump to take this to the Supreme Court today. If he doesn’t, then the stay expires and Judge Chutkan can start getting ready for trial. And although, formally, Trump could still seek certiorari (and a stay) at some future date without filing today, the fact that he could have kept the trial on hold but didn’t would weigh very heavily against such relief down the road. An old maxim for these kinds of equitable remedies is that “[h]e who comes into equity must come with clean hands.” So too, here.

III. What Happens at the Supreme Court?

The specific application Trump files will almost certainly ask the Court to “stay” (i.e., freeze) the D.C. Circuit’s mandate pending its disposition of a (forthcoming) petition for certiorari in the Supreme Court. In other words, “I’m going to appeal the D.C. Circuit’s ruling at some point. Until I do, please keep the trial on hold.” It goes to Chief Justice Roberts in the first place in his capacity as Circuit Justice for the D.C. Circuit, and Roberts will quickly order a response from Special Counsel Jack Smith, who represents the federal government in this case. But contra some accounts you might’ve read last week, there is no need for Roberts to issue an “administrative stay” that temporarily pauses things while the Supreme Court considers Trump’s request. Again, the D.C. Circuit’s mandate cleverly keeps the mandate paused while the Supreme Court considers Trump’s application, so nothing happens to the D.C. Circuit’s mandate until Roberts or the full Court rules on Trump’s application. (It’ll be the full Court.)

As for what the full Court will do, I see four options,1 although only two strike me as reasonably likely:

Deny Trump’s application for a stay. This would be the biggest headline, for the Court would be unambiguously signaling that it is okay with the January 6 prosecution proceeding to trial. The Court wouldn’t formally be taking a position on the underlying immunity question (such an order would almost certainly have no explanation), but this would signal that no more than four justices (and perhaps fewer) think Trump is likely to win on the immunity issue. Judge Chutkan could restart the clock as soon as this order comes down. Trump might still seek certiorari from the D.C. Circuit’s ruling, but the writing would be on the wall for how the Supreme Court would rule on such a petition (they’d deny it).

Grant the application for a stay, and say nothing else. A lot of folks on the internet are worried about this one—where the Court would keep the January 6 prosecution on hold, but leave to Trump the full timeline available for seeking rehearing from the full D.C. Circuit and certiorari from the Supreme Court. This outcome would effectively make it impossible for the January 6 prosecution to resume before the election, as the Court wouldn’t even be in a position to grant certiorari until June at the earliest (and, more likely, September). I really don’t see this happening, but more on this below.

Grant the application for a stay, treat it as if it were also a cert. petition, grant that petition, and set the case for expedited briefing and merits argument. This result may sound convoluted, but it makes a lot of sense from the Court’s perspective. It would allow the justices to keep the January 6 prosecution paused for just long enough to decide whether the D.C. Circuit was correct, but it would also allow them to decide that question quickly, to avoid the specter of running out the clock on behalf of former President Trump. If the Court went this path, I’d expect a mid-to-late March or early April argument, with a ruling by the end of May.

Treat the application as a cert. petition, grant the petition, and summarily affirm the D.C. Circuit. This one seems unlikely to me, but not beyond the realm of possibility. The Court can (and sometimes does) issue merits rulings at the cert. stage—but usually in order to reverse or vacate the decision below. The easiest way to summarily affirm a lower-court ruling is usually to just refuse to review it by denying certiorari. A summary affirmance here would be a way to provide a more affirmative endorsement of the court of appeals’ disposition—albeit one that would require six votes.

Two of these dispositions (the first and fourth) would immediately clear the way for the January 6 trial to proceed. The third one would likely still allow for a trial sometime this summer. And the second one would … not.

It seems to me that the most likely outcomes are either the first (deny the stay) or the third (grant the stay and expedite plenary merits review). Here’s why:

First, I just don’t think there are five votes (or even four) among the current justices for the proposition that a former president is absolutely immune from criminal prosecution for acts committed while he was president. Maybe there’s wiggle room about whether some acts might be protected, but the D.C. Circuit’s ruling doesn’t foreclose that possibility, and the justices could reasonably conclude that they can save that issue for a case in which it really matters. And if there isn’t a clear majority (or chance at a majority) to reverse, then running out the clock would make the Court look really bad—all the more so because there would almost certainly be loud public dissents from those justices who wanted to either deny the stay or to expedite the Court’s plenary review. Thus, although there appear to be a lot of people worried about the Court pursuing Option 2 from above, I just don’t think it’s especially likely. It seems to me that the real choice for the Court is to get all the way in (grant, expedite, and decide quickly) or to stay all the way out (deny).

Second, and related, Trump’s application reaches the Court as it is voting on the Colorado ballot disqualification case. I suspect that there are at least some justices who would welcome the chance to split the difference between the two disputes—Trump gets to be on the ballot, but he also gets to be prosecuted, and then the Court has let the chips fall as they may. The closer in time to its ruling in the Colorado case that the Court clears the way for the January 6 prosecution to go forward, the more it can capitalize upon such a transparently political compromise.

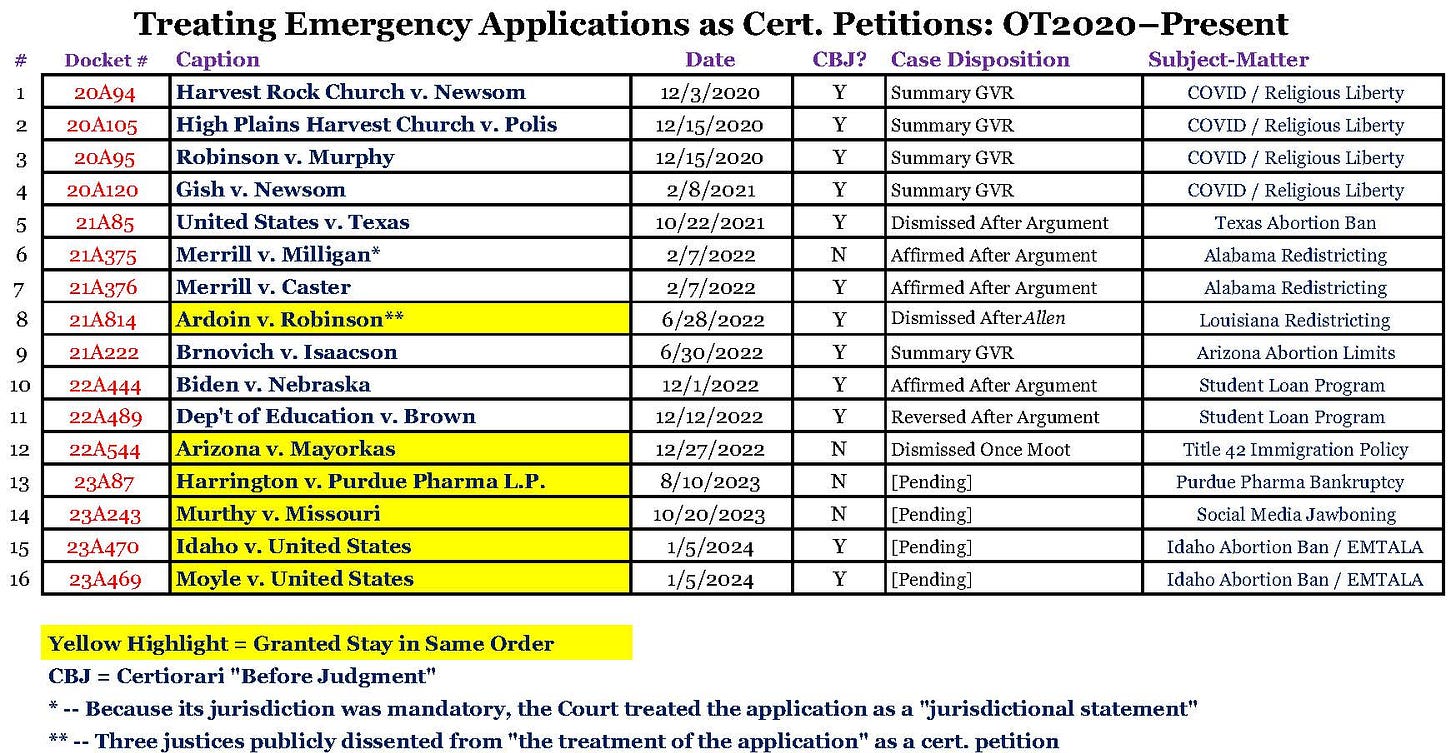

Third, although the “treat-as-a-cert.-petition-and-grant” move might seem the most complicated, it’s actually become far more common in recent years. As the Court has used the emergency docket much more aggressively since 2016 (and especially since 2020), it has also been taking a higher number of emergency applications and treating them as cert. petitions than ever before. After using this move roughly once a term for the first 15 years of Chief Justice Roberts’ tenure, since the beginning of the October 2020 Term, the Court has pursued this exact same procedural path on 16(!) different occasions (including in four of the cases the Court is hearing on the merits during its current term):

Given how often the Court has done this in other contexts, it would be hard to argue against such a move on the ground that this case isn’t sufficiently important. Thus, if there are five votes to grant a stay, it seems likely that there would also be a consensus to expedite the merits and resolve the immunity issue this term (i.e., by the end of June at the absolute latest, and quite possibly sooner).

Finally, I don’t think it will matter that much what Jack Smith says in his response. Yes, in seeking certiorari before judgment (that is, before the D.C. Circuit’s review) back in December, Smith had argued that it was imperative for the Supreme Court to resolve this issue before the trial could go forward. And I don’t doubt for a second that Trump’s lawyers (and his supporters) will use that line against Smith if Smith opposes the stay that Trump will shortly seek. But the justices aren’t ever bound by the parties’ statements / preferences in this respect, especially when no court has previously relied upon them (a prerequisite for the doctrine of “judicial estoppel”). Either the Court wants to decide this issue or it doesn’t. If it does, it would be easy enough to decide it quickly—to avoid the charge that the justices are playing partisan politics with their docket. And if it doesn’t, then what Smith said in December isn’t going to change the justices’ minds. Simply put, whether the Court steps in or not is just not going to depend upon what Smith has said.

All of this is a long way of saying that my best guess is that the Court either denies Trump’s application for a stay outright (clearing the way for the January 6 prosecution to go forward immediately) or grants it, but in an order that also grants certiorari and sets an expedited schedule for briefing and oral argument (which could lead to a decision by sometime in May or June that clears the way for trial). As for when such an order will come down from the Court, the justices are under no deadline of their own. I’d say this Friday is the earliest possibility, but sometime next week is much more likely. If we get to two weeks from today without hearing from the Court, I’ll be more than a little surprised.

But, as they say, “your mileage may vary.”

SCOTUS Trivia: The One Justice to Play in the NFL

In light of last night’s sportsball news, I thought it would be a good (if obvious) opportunity to highlight the career of the one justice to have played professional football—Justice Byron (“Whizzer”) White.

An All-American halfback at the University of Colorado, White finished second in the 1937 Heisman Trophy balloting, and was drafted in 1938 by the Pittsburgh Pirates (no, not those Pirates; the Steelers were also known as the Pirates until 1939). White led the NFL in rushing yards during his rookie season, took a year off as part of the Rhodes Scholarship, and then played two years for the Detroit Lions (leading the NFL in rushing again in 1940) before being called away for military service during World War II. Upon completing his service (as a decorated intelligence officer), White chose law school instead of more football, and the rest was history.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one. This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning. And we’ll be back with a regular issue next Monday.

Until then, happy Monday, everyone! I hope that you have a great week.

There are other options that are at least theoretically possible (like a summary reversal), but I’m only considering the realistic ones here.

If SCOTUS reverses the Colorado Supreme Court saying that states can’t independently disqualify presidential candidates under Section 3 - then what would be the criteria for a state to disqualify a presidential candidate? Or is that one of the thorny bits a narrow ruling would sidestep?

Is there a compelling reason for the Chief to ask for a response from the government if the Court members intend to deny cert? I guess I'm asking if, on the shadow docket, a response is always requested. Thanks!