65. Lincoln, Taney, and Ex parte Merryman

The most direct clash between a President and a Chief Justice arose from one of the strongest possible cases for unilateral executive power—and there's still room for debate about who was right.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

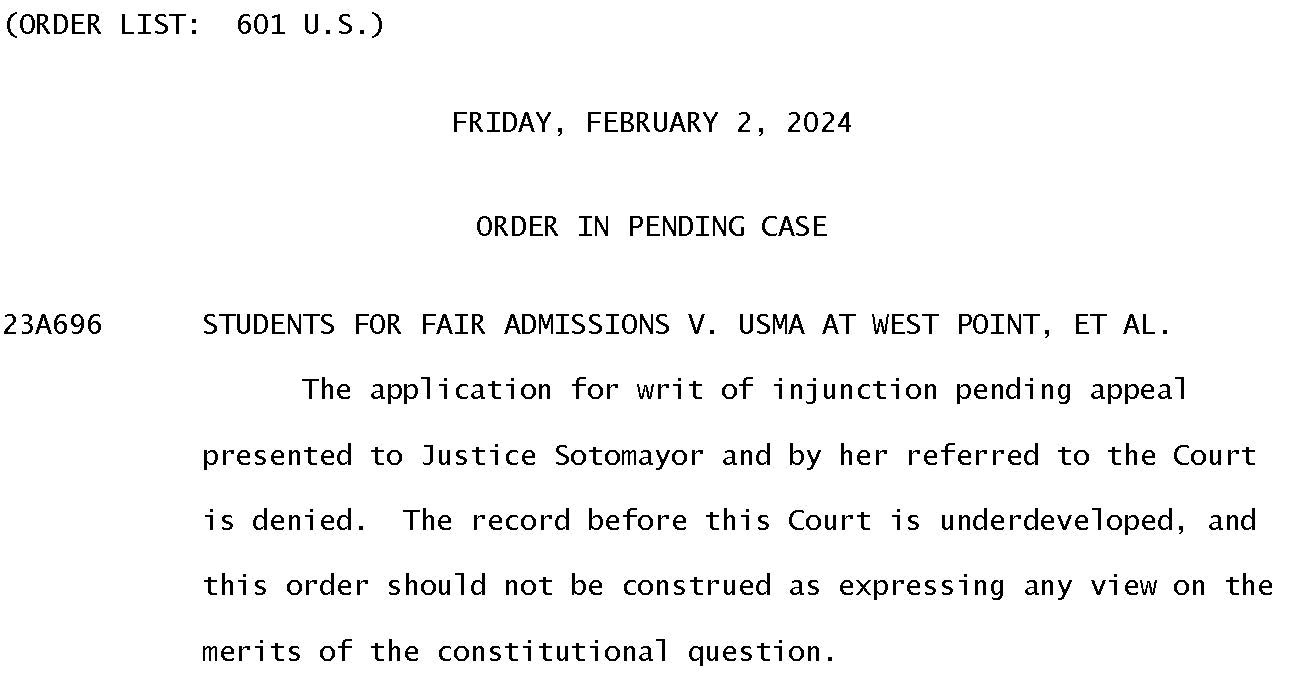

The Court was still in its mid-winter recess last week, and issued only two orders. The first was a housekeeping order relating to this Thursday’s much-anticipated oral argument in Trump v. Anderson—on whether former President Trump is disqualified from future office under Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment. The second was a denial of an application for emergency relief by the plaintiffs in last term’s blockbuster affirmative action cases, who are now challenging the continuing use of racial preferences by the military’s service academies. Quite unusually, the unsigned order went out of its way to emphasize that “The record before this Court is underdeveloped, and this order should not be construed as expressing any view on the merits of the constitutional question.”

Given the Court’s repeated insistence that unsigned, unexplained orders have no precedential force, this sentence is more than a little strange. My own view is that it (1) was likely necessary to keep some number of justices from publicly dissenting (or at least writing separately); and (2) implies exactly the opposite of what it says. Or, if you prefer this point as a meme, my “this order doesn’t express a view on the merits” t-shirt has people asking a lot of questions already answered by my t-shirt.

Obviously, Thursday’s oral argument in the Trump disqualification case is the biggest headline we expect from the Court this week. (For my earlier discussion of the case, see here.) We also expect at least one opinion in an argued case right before that argument begins—at 10:00 ET Thursday morning. Given that the Court has only handed down one ruling thus far, it seems too early for anything especially divisive; and there are plenty of (less-significant/less-divisive) cases argued in October or November that could be ripe.

The justices didn’t have a regular Conference last week, so no Order List is expected today. And although there are one or two emergency applications kicking around, I don’t think any of the pending ones are likely to be referred to (or decided by) the full Court. In other words, this week is all about the Trump disqualification case.

The One First “Long Read”: Ex parte Merryman

On April 15, 1861 (the day after Fort Sumter surrendered), President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation declaring the Southern states to be in a state of insurrection and calling for 75,000 men to put down the uprising. The first order of business was reinforcing the nation’s capital, which, all of a sudden, found itself between a rock and a hard place—surrounded on one side by Virginia, which voted to secede (and seized federal armories at Harper’s Ferry and the Gosport Navy Yard) on April 18, and on its other three sides by Maryland, a slave state that was at substantial risk of following suit.1

As the late Chief Justice Rehnquist described in his book, All the Laws But One,

Baltimore was an absolutely critical rail junction for the purpose of bringing troops from the north or west into Washington, because the railroad coming down the coast from New York and Philadelphia, as well as the line from Harrisburg, ran through that city. . . . This strategic location, plus the substantial degree of secessionist sympathy in Baltimore, made the city the Achilles’ heel of the early efforts to bring federal troops to defend Washington. And the status of Maryland as a border state, whose adherence to the Union was problematic, exacerbated this difficulty. Maryland teetered both geographically and ideologically between North and South. If the secessionists were to gain the upper hand, the Union war effort could be seriously compromised.

Thus, it was little surprise when, on April 19, a mob of Confederate sympathizers attacked a regiment of Massachusetts volunteers as it moved through Baltimore on its way to Washington. After the incident, several railroad bridges north of Baltimore were burned, and President Lincoln agreed to cease transporting troops through Baltimore, opting instead for a detour by sea from Perryville, north of Baltimore, to Annapolis, and then by land to Washington. In the interim, Washington was effectively cut off from the North, with irregular mail deliveries, no telegraph service, and, as importantly, no new troops.

Although Lincoln refused to interfere with a special session of the Maryland legislature called for April 26, and although troops eventually had arrived in Washington on April 25, Secretary of State William H. Seward and General Winfield Scott, Commanding General of the Union Army, were adamant that the pro-Confederate forces in Baltimore posed a continuing and potentially catastrophic threat to the security of the capital. And although Lincoln had called for Congress (which had been out of session since March 28) to reconvene, that wouldn’t happen until July 4. With only his own inherent authority to go on, Lincoln issued an order to Scott on April 27, which would not become public for several months, authorizing the suspension of habeas:

You are engaged in suppressing an insurrection against the laws of the United States. If at any point on or in the vicinity of any military line which is now or which shall be used between the city of Philadelphia and the city of Washington you find resistance which renders it necessary to suspend the writ of habeas corpus for the public safety, you personally or through the officer in command at the point at which resistance occurs, are authorized to suspend that writ.

On May 13, 1861, Union troops entered and occupied the City of Baltimore, which would remain under military control for the duration of the war. Twelve days later, around 2:00 a.m. on Saturday, May 25, 1861, a detachment of federal troops entered the Cockeysville, Maryland house of John Merryman and arrested him on suspicion of being involved in the destruction of railroad bridges and telegraph lines north of Baltimore on April 19.

Merryman, a pro-slavery Democrat and an officer in the Baltimore County Horse Guards, was imprisoned at Baltimore’s Fort McHenry, where he was given immediate access to counsel. His lawyers drafted a petition for a writ of habeas corpus, and presented it to Chief Justice Taney at his Washington home later that afternoon. Taney convened a short hearing on the application for the writ on Sunday morning, May 26, at the Masonic Hall in Baltimore (where the federal district and circuit courts sat), and issued the writ, addressed to General George Cadwalader—commander of the military district including Fort McHenry—returnable at 11:00 a.m. on Monday, May 27. (At that time, and until the 1940s, a writ of habeas corpus would issue to initiate the proceeding, not to reflect the court’s conclusion that the detainee should be released.)

Cadwalader did not appear on the twenty-seventh, sending instead Colonel Lee, his aide-de-camp, who, resplendent in full dress uniform complete with a sword and a red sash, read a formal written response invoking the suspension and declining to produce Merryman. Merryman's counsel formally asked Lee if he had produced Merryman, which, Lee responded, he had not. Taney then issued an attachment against Cadwalader for contempt for failing to comply with the writ of habeas corpus, returnable the next day, May 28, at noon.

When court convened on Tuesday, May 28, neither Cadwalader nor any of his adjutants appeared. Taney asked the U.S. Marshal for the District of Maryland, Washington Bonifant, if he had served the attachment on General Cadwalader, and Bonifant said he had attempted to do so, but was not permitted to enter Fort McHenry. In other words, it was the attachment intended to make the writ of habeas corpus enforceable that couldn’t be served on federal military authorities.

Taney then delivered a short opinion from the bench, emphasizing that the President had no authority to suspend habeas corpus and that military officers had no authority to arrest and detain a civilian or to refuse to surrender such an arrestee to civilian authorities. Although the marshal had legal authority to summon a posse comitatus to bring General Cadwalader before the court, Taney recognized that “the power refusing obedience was so notoriously superior to any the marshal could command” that Bonifant was excused from any further responsibility. Taney concluded by noting that he would file a written opinion, and would forward a copy of such to President Lincoln, “in order that he might perform his constitutional duty, to enforce the laws, by securing obedience to the process of the United States.”

Throughout the formal opinion that he filed on June 17, Taney seized on two propositions he found equally immutable: that only Congress could provide for suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, and that only members of the military could be subjected to military jurisdiction and thereby exempted from the process of civilian courts. The Constitution only conferred limited authority on the President, and that authority did not extend to the extrajudicial detention of civilians:

In such a case, my duty was too plain to be mistaken. I have exercised all the power which the constitution and laws confer upon me, but that power has been resisted by a force too strong for me to overcome. It is possible that the officer who has incurred this grave responsibility may have misunderstood his instructions, and exceeded the authority intended to be given him; I shall, therefore, order all the proceedings in this case, with my opinion, to be filed and recorded in the circuit court of the United States for the district of Maryland, and direct the clerk to transmit a copy, under seal, to the president of the United States. It will then remain for that high officer, in fulfillment of his constitutional obligation to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed,” to determine what measures he will take to cause the civil process of the United States to be respected and enforced.

Afterward, Taney, who had initially suspected that he might himself be imprisoned by the end of the proceedings,2 famously told the Mayor of Baltimore that “I am an old man, a very old man . . . but perhaps I was preserved for this occasion.”

Notwithstanding the wide-scale (and wide-ranging) public reaction occasioned by Taney’s opinion, President Lincoln did not publicly react until his July 4 address to Congress:

This authority [suspending habeas] has purposely been exercised but very sparingly. . . . The whole of the laws which were required to be faithfully executed, were being resisted, and failing of execution, in nearly one-third of the States. Must they be allowed to finally fail of execution, even had it been perfectly clear, that by the use of the means necessary to their execution, some single law, made in such extreme tenderness of the citizen's liberty, that practically, it relieves more of the guilty, than of the innocent, should, to a very limited extent, be violated? To state the question more directly, are all the laws, but one, to go unexecuted, and the government itself go to pieces, lest that one be violated? Even in such a case, would not the official oath be broken, if the government should be overthrown, when it was believed that disregarding the single law, would tend to preserve it? But it was not believed that this question was presented. It was not believed that any law was violated. . . . It was decided that we have a case of rebellion, and that the public safety does require the qualified suspension of the privilege of the writ which was authorized to be made. Now it is insisted that Congress, and not the Executive, is vested with this power. But the Constitution itself, is silent as to which, or who, is to exercise the power; and as the provision was plainly made for a dangerous emergency, it cannot be believed the framers of the instrument intended, that in every case, the danger should run its course, until Congress could be called together; the very assembling of which might be prevented, as was intended in this case, by the rebellion.

Thus, Lincoln argued, the suspension was justified both by the Constitution's text and by the exigencies of the situation—especially in a circumstance in which Congress was out of session and wouldn’t be able to meet again for some time. To the former, Lincoln harped on the Constitution’s failure to specify that only Congress can suspend the writ. To the latter, Lincoln raised the specter of the existential threat to the Union that may well have resulted from Maryland’s secession. Moreover, Lincoln implicitly suggested that the two points were linked, for the lawlessness in Baltimore itself jeopardized Congress’s ability to meet and to thereby provide authorization for Lincoln’s actions.

But perhaps reflecting some doubt as to the legal arguments, Lincoln did not appeal Taney’s decision to the full Court. And although Congress passed a sweeping statute in August 1861 purporting to ratify all of the actions Lincoln had taken while Congress was out of session, there’s at least some debate as to whether that statute encompassed (or even could encompass) his unilateral suspension of habeas corpus—just like there remains debate as to whether Lincoln’s legal (as opposed to moral) argument was in any way persuasive. In many ways, that debate continues today. (For a third view, I wrote an article some time ago offering an alternative ground on which both Taney and Lincoln could have been correct—that Lincoln’s actions in response to the violence in Baltimore were consistent with pre-existing statutory grants of authority to “suppress Insurrections”.)

As for John Merryman, on July 12, 1861, at the request of Attorney General Bates, Merryman was released “to the civil authorities.” He was subsequently indicted for treason in the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Maryland but was released on bond and returned home on July 25, two months to the day of his initial arrest. Moreover, due to intentional obstruction by (and the declining health of) Chief Justice Taney, Merryman became one of hundreds indicted for treason in the Baltimore circuit court whose case never went to trial.

Ultimately, Merryman was elected to the Maryland House of Delegates in 1874. In December 1864, two months after Chief Justice Taney had died, Merryman and his wife, Anne Louise, gave birth to a baby boy. They named him Roger Brooke Taney Merryman.

SCOTUS Trivia: Taney and Inaugurations

Shortly before then-President-Elect Obama was sworn in by Chief Justice Roberts in 2009, a reporter asked me whether that was going to be the most awkward swearing-in in American history (since then-Senator Obama had voted against Roberts’s confirmation in 2005). Given the … animosity … between Lincoln and Taney (and, it should be said, between Thomas Jefferson and John Marshall), I demurred.

But it did prompt an interesting trivia question: Which Chief Justice swore in the most different presidents? Marshall easily holds the record for the most swearings-in overall, having presided over nine different inaugurations during his 34+ years on the Court. But four of those were for the incumbent President’s second term (Jefferson in 1805; Madison in 1813; Monroe in 1821; Jackson in 1833). So Marshall swore in only five different presidents.

The record, it turns out, belongs to Taney, who swore in seven different presidents, beginning with Martin Van Buren in 1837. Taney swore in Van Buren; William Henry Harrison (in 1841); James K. Polk (in 1845); Zachary Taylor (in 1849); Franklin Pierce (in 1853); James Buchanan (in 1857); and Lincoln (in 1861). What’s more, two other presidents served during Taney’s 28-year tenure; both John Tyler and Millard Fillmore were sworn in by William Cranch (the Chief Judge of the D.C. Circuit), since their swearings-in were … irregular.

If you’re wondering, 2025 will be Chief Justice Roberts’s fifth inauguration, but he still has some work to do to catch Taney; to date, he has sworn in only three different presidents.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one. This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning. And we’ll be back with a regular issue next Monday.

Until then, happy Monday, everyone! I hope that you have a great week.

This discussion is adapted from my 2007 Temple Law Review article, “The Field Theory: Martial Law, the Suspension Power, and the Insurrection Act.”

There is a well-trodden conspiracy theory that Lincoln had indeed sworn out an arrest warrant for Chief Justice Taney, but there is no contemporaneous physical or even circumstantial evidence supporting it.

A wonderful history lesson. Conservatives were opposed to the Unitary Executive before they were for it. I'm often surprised that the GOP has not impeached President Lincoln, posthumously. Honest Abe fully understood that the law is far more than a tort. It's the defender of speech, petition, assembly and religious pluralism. Or at least it was before BvG's John Roberts came along. BvG disenfranchised ballots from minority voters at more than ten times the rate of Caucasian ballots. Sepsis Sam forced swing-state voters to stand in line during a pandemic, by outlawing ballots mailed on Nov3rd. Husted tosses them off the rolls for skipping an election, thereby reversing the burden of proof on ballot eligibility. Substantive due process reduces to procedural due process. If our ballot is denied or destroyed, our opinions are nothing more than coffee talk.

In David McCullough’s wording on Ken Burns’ THE CIVIL WAR, President Lincoln saved the Constitution in this instance by going “beyond it.” Whether Chief Justice Taney hindered President Lincoln’s efforts to defend Washington in the early days of the war (and arguably violated HIS oath of office) is a matter for historians to discern. The fact that the President considered, however briefly, arresting the Chief Justice, however, suggests something about Taney’s intention and desire.