63. Chevron and the Unitary Executive

The Supreme Court's recent jurisprudence expanding presidential control of the bureaucracy undermines one of the common critiques of judicial deference to executive branch interpretations of statutes

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

Once again, the biggest news out of the Court last week was the absence of news. Tuesday’s regular Order List had no surprises; and the Court took no action on either the Biden administration’s emergency application in the concertina-wire dispute with Texas (one of the three pending legal fights between Texas and the federal government over the U.S.-Mexico border that I covered in length in last Thursday’s bonus issue); or the emergency application in the Michigan state redistricting case (which I wrote about last Monday). Frankly, I’m more than a little surprised about the Court’s lack of movement in the Texas case; perhaps that’s just because there is a lengthy separate opinion respecting the disposition coming. But as I wrote on Thursday, delay here isn’t neutral given that there is currently an injunction in place blocking the federal government from removing physical impediments to reaching the border. Suffice it to say, I’ll be even more surprised if the justices don’t rule on the application this week.

There’s also a new emergency application from Alabama death-row prisoner Kenneth Eugene Smith, seeking to block his impending execution while the justices consider his cert. petition. In particular, Smith is challenging Alabama’s plan to use nitrogen gas to execute him after it botched its first attempt to execute him by lethal injection in November 2022 (an attempt that the Supreme Court had cleared the way for after the Eleventh Circuit had blocked it). Smith is arguing that the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment prohibits multiple attempts to execute a prisoner if the reasons for the prior failures are willful on the state’s part, rather than inadvertent. Given that the execution is currently scheduled for this Thursday, expect the Court to rule at least on the emergency application before then.

Otherwise, we expect a regular Order List at 9:30 ET, but oral arguments for January have concluded (the next argument is the February 8 argument in the Trump disqualification case). And there’s no indication on the Court’s website that any opinions in argued cases are expected this week. So once again, rulings on emergency applications are the most likely source of big headlines from the Court in the next seven days.

The One First “Long Read”: Chevron Deference, Democratic Accountability, and Executive Control

By far, the most anticipated arguments of the Court’s January session came last Wednesday, in the Relentless and Loper Bright cases. Both of those cases involve the same basic question: Should the Court overrule, or at least heavily circumscribe, its 1984 decision in Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council—which articulated the principle now known as “Chevron deference”: that, when there is ambiguity in a statute that delegates power to an executive branch agency, courts should “defer” to (i.e., accept) the agency’s interpretation of the ambiguity so long as that interpretation is “reasonable.” In other words, agencies, not courts, should have the final say when it comes to the meaning of ambiguous terms in statutes those agencies enforce.

There’s a lot to say (much of which has been said) about how we got from 1984 (when Chevron was quite popular among legal conservatives) to today (when it has become a bête noire). The basic critique today focuses on the transfer of power Chevron effects—from Congress (which has the power to resolve the ambiguities at issue) to executive branch agencies. And although that critique has many facets, at its core is the idea that those agencies are less democratically accountable than Congress. As opposed to having questions of agency power resolved by those elected to resolve them, the concern is that Chevron empowers faceless low-level federal bureaucrats for whom no one voted, and who no one could name.

A common response to that objection is that a world without Chevron is a world in which those interpretive questions won’t be answered by Congress; they’ll be answered by even less democratically accountable federal judges—who are the real “victims” of Chevron deference. After all, if a statute is ambiguous, the real question Chevron asks is whether the agency or the reviewing court is better situated to resolve the ambiguity. To be sure, some of Chevron’s critics argue that this is a false dichotomy—that the real point is that Congress ought to be forced to be clear in all of its delegations to agencies. (This is basically the point of the major questions doctrine—which now requires such clarity on issues of “vast economic or political significance.”)

But contemporary congressional dysfunction aside, it just isn’t realistic to expect Congress to legislate with micro-specificity across every single inch of regulatory real estate—especially in cases without the “vast economic or political significance” of major questions (where sustained congressional attention is unlikely). That’s not a point about politics; it’s a point about parliamentary capacity. There are somewhere north of 430 federal agencies; even if Congress devoted one calendar day each year to one agency, it wouldn’t get to all of them. Thus, the debate in the typical case is usually going to reduce to a choice between leaving the power to resolve the interpretive dispute to the agency’s reasonable discretion or to the courts. Whatever the pros and cons of the two sides in that debate, it’s clear that the case for the courts in that situation is not about increasing democratic accountability.

Instead of focusing on that dynamic, though, I want to flag a different point that ought to be relevant to any conversation about the democratic accountability of executive branch agencies, but has largely been missing from recent discourse about Chevron (including at Wednesday’s arguments): How, in recent years, the Supreme Court itself has made executive branch agencies more democratically accountable, at least on paper. Whatever one thinks of the Court’s aggressive move toward the “unitary executive” theory of presidential control of the executive branch bureaucracy, it seems, at the very least, that it’s in significant tension with the argument that deference to agencies is problematic because the relevant decisionmakers at those agencies are not accountable to the people. To whatever extent that was true in 1984, it’s far less true today.

The “unitary executive” theory of presidential power is the idea that Article II of the Constitution, by vesting “the executive power” in a single person (the President), gives that person indivisible (“unitary”) control over the executive branch, including over the actions (and, if necessary, removal) of all of his subordinates. Thus, anyone who wields executive power must be directly accountable to the President, or else that arrangement unconstitutionally deprives the President of his unitary control. Although unitary executive theory is often defended on (highly disputed) originalist grounds, it also has a democratic accountability hook: unlike the Administrator of the EPA or the Assistant Secretary of Transportation, we vote for the President. Thus, ensuring that the President can directly control his subordinates improves the democratic accountability of their decisionmaking.

To be sure, there are lots of objections to the unitary executive theory, many of which I find compelling. The relevant point for present purposes is that, in the last 14 years, the Supreme Court has taken three major steps toward embracing it in the context of presidential control of the administrative state. Those steps have had the effect of bringing far more of the federal bureaucracy under the President’s direct control. And whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing in the abstract, it sure seems to pour cold water on claims that judicial deference to those agencies is generally un- (or even anti-)democratic.

First, the Court has moved the line between the two types of executive branch officers contemplated by the Constitution’s Appointments Clause: “principal” officers and “inferior” officers. Principal officers, the Court has long held, must be subject to plenary control by the President (they “serve at the pleasure of the President”). Thus, although the Senate has to confirm them, once confirmed, the President can fire them at any time and for any reason.

Inferior officers, in contrast, can be appointed by someone other than the President, and, at least under older precedents (more on those in a moment), Congress can protect them from direct presidential control by imposing “for cause” restrictions on their removal. But in its 2021 decision in United States v. Arthrex, Inc., a 5-4 majority (with Justice Thomas joining the Democratic appointees in dissent) clarified the line between principal and inferior officers in a way that places far more executive branch officers into the former category than previously. (In that case, that included “Administrative Patent Judges.”) Under Arthrex, more executive branch officers are “principal” officers who, constitutionally, must be directly accountable to the President.

Second, even with respect to those who are still inferior officers, the Court has heavily circumscribed Congress’s ability to insulate those officials from direct presidential control. First, in its 5-4 ruling in Free Enterprise Fund v. PCAOB in 2010, the Court held that two layers of “for-cause” removal protections are unconstitutional—meaning that, even if some inferior officers can only be removed for cause, the officers with the power to remove them must themselves be directly answerable to the President. And second, in its 2020 decision in Seila Law v. CFPB, a 5-4 majority (sensing a theme?) held that, as opposed to independent agencies with multi-member heads (like the FTC, FEC, or SEC, the commissioners of which can be insulated from direct presidential control), where an agency has a single head (like the CFPB), that person can not be insulated from direct presidential control. The Court left intact, for the moment, its older rulings in Humphrey’s Executor and Morrison (recognizing contexts in which for-cause removal protections were constitutional), but reframed those rulings as “exceptions” to the general rule that all executive branch officers should be subject to the President’s direct control—because “Under our Constitution, the ‘executive Power’—all of it—is ‘vested in a President,’ who must ‘take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.’”

Third, and perhaps most significantly (by volume), the Court also adjusted the line between “officers of the United States” (to whom these first two developments apply) and mere “employees” (to whom they don’t). In its 2018 ruling in Lucia v. SEC, a 6-3 Court (with Justice Kagan joining the Republican appointees in the majority) held that even administrative law judges resolving administrative disputes in the SEC are “officers,” not employees—in an opinion that arguably shifts thousands of executive branch personnel from the employee side of the line to the officer side.

Reasonable minds can dispute the merits of each/all of these rulings. What can’t be denied is their upshot: Today, to a degree that is radically different from what was true in 1984 (or even 2009), the President is constitutionally entitled to exercise direct control over much more of the administrative state—indeed, almost all of it. To drive the point home, just last week, a Fifth Circuit panel begrudgingly followed Humphrey’s Executor, but only because the Supreme Court hasn’t overruled it yet. Yes, there are still a handful of executive branch officials who are protected to at least some degree from direct presidential supervision. But as Seila Law makes clear, they are now the exception, not the rule.

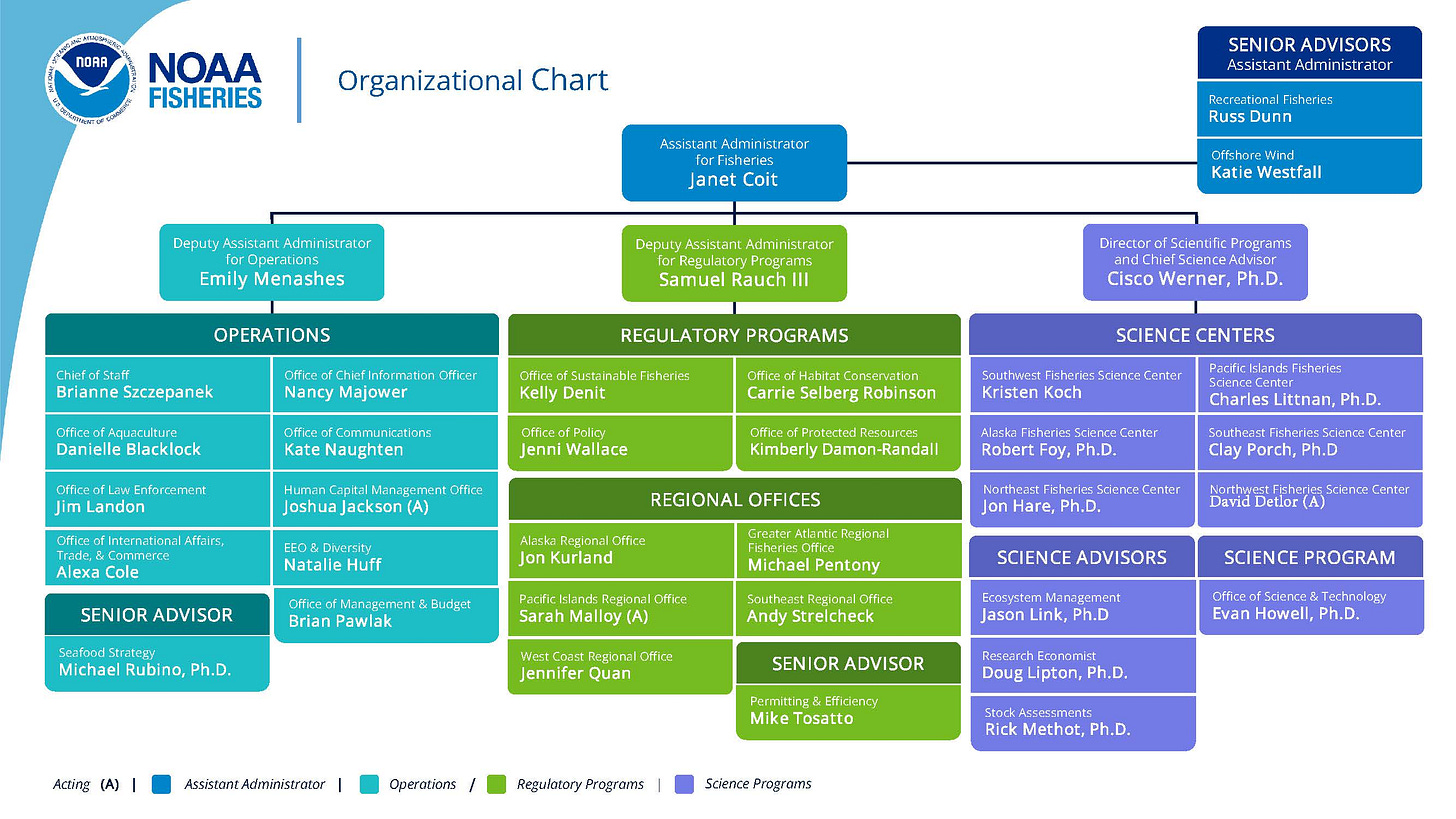

To illustrate the point, consider the agency the regulations of which are at issue in Relentless and Loper Bright—the National Marine Fisheries Service (part of NOAA). It is headed by the Assistant Administrator for Fisheries (currently Janet Coit), who is appointed by the Secretary of Commerce “subject to approval of the President,” with no insulation against being removed at will. Thus, if voters have a problem with how the NMFS is interpreting its statutory authority, it’s a direct line from the President to the head of the agency responsible for that interpretation.

I don’t mean to overstate the point; there are other objections to Chevron, and there are lots of historical, analytical, and practical objections to the Court’s move toward the unitary executive theory in the cases surveyed above. But there’s a tendency among lots of folks who write and talk about the Court to approach and conduct doctrinal debates in a vacuum—without accounting for how developments in related but distinct cases might alter the underlying calculus. (This comes up a lot, for instance, in how pleading standards relate to causes of action relate to immunity defenses.) And insofar as one objection to Chevron deference is that it gives too much power to unaccountable executive branch bureaucrats, that objection is increasingly hard to square with the Supreme Court’s decades-long quest to make those bureaucrats more directly accountable. Whatever the Court ultimately does with/to Chevron, hopefully it at least acknowledges the consequences of its own shifts in related doctrinal contexts.

SCOTUS Trivia: The Attorney General and the Unitary Executive

I’ve written about this one before, but it’s too topically perfect to not re-up today: When Congress created the office of Attorney General in section 35 of the Judiciary Act of 1789, it was clear about what that officer’s functions were (there were two: representing the United States in the Supreme Court and giving opinions on legal matters to any government official or body seeking them). But it was deliberately vague about who would appoint the officeholder. Unlike the “secretaries” of the “executive” departments Congress had established a few weeks earlier (“Foreign Affairs,” Treasury, and “War”), Congress was ambiguous as to whether the Attorney General was an executive officer, a judicial officer, or some hybrid of the two.

One of the reasons for the ambiguity in the final bill is because the version of the Judiciary Act initially passed by the Senate would have vested the appointment power in the Supreme Court. (One state—Tennessee—still follows this model today.) Indeed, only a handful of states have attorneys general who are appointed by the governor; most states directly elect their attorney general (and Maine’s is appointed by the state legislature).

The passive voice in section 35 was, it turns out, almost certainly a punt. President Washington nevertheless filled the office (with Edmund Randolph), setting a precedent that the Attorney General would be appointed by the President. And in 1870, Congress made explicit the “executive” nature of the office as part of the statute creating the Department of Justice. But for those who claim that Founding-era materials unambiguously support the unitary executive theory, the fact that the Founders weren’t even clear as to whether the Attorney General should be subject to the President’s exclusive direction and control sure seems like a significant piece of contemporaneous evidence to the contrary.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one. This week’s bonus issue—featuring the January installment of “Karen’s Corner”—will drop Thursday morning. And we’ll be back with a regular issue next Monday.

Until then, happy Monday, everyone! I hope that you have a great week.

The thing that bugs me about the coverage of the Chevron Defense is how many people think the deference is absolute. "So long as the interpretation is reasonable" is the critical part. There are already lots of avenues for litigants to challenge administrative decisions in the courts, ALJs or even more. In fact, the fishing boat litigant seems to have done so: I understand the the fee he objected to has actually been dropped in his case.

The folks litigating "on behalf" of the fisherman are indeed doing no such thing. They are litigating on behalf of an agenda.

It's too much to hope that the Extremes should just modify the concept, to add better ways to challenge an administrative decision on existing reasons for challenge. If it isn't true already, awarding attorney fees to a prevailing litigant could allow greater access to using the existing exceptions to deference.

In other words, to freaking BALANCE the "unaccountable" agency's expertise with some further accountability in the courts, rather than let judges simple pontificate on issues of expertise they know nothing about.

Unitary Executive=King George, who never asks. He takes. Back in the early 80s, exiled Iranian President Abolhassan Banisadr routinely appeared on French network television, signed paperwork (earlier agreement) from the Carter Administration in hand, to inform us that George Bush (and earlier, Bill Casey) had furtively met with the ayatollahs (same hotel that Kissinger used, to disrupt the Vietnam peace talks) in order to convince them to delay release of the embassy hostages until after the election so that Carter would lose. The clerics were only too happy to agree, because they hated Jimmy Carter for feting the Shah (an American puppet) at WH state dinners. The hostages were released ten minutes after the conclusion of Reagan's inaugural address. In return, Gipper sold TOW and Hawk missiles (through Jerusalem, of all places) to the nation his own State Dept had listed as the primary sponsor of international terrorism. Never told Congress.