59. Justice Davis and the Electoral Commission of 1877

A single vote by a single justice ended up handing the Election of 1876 to Rutherford B. Hayes; it just wasn't from the justice who was supposed to play that role

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday (even holidays like today), I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

Last week was … a busy one. I already wrote about the Colorado Supreme Court decision on Tuesday holding that former President Trump is disqualified from holding future office, and what that could mean for the U.S. Supreme Court. But beyond that news, there were at least two other significant developments:

First, on Friday, the Court denied Special Counsel Jack Smith’s petition for certiorari “before judgment” on whether former President Trump is immune from prosecution for acts relating to and arising out of January 6. The summary order offered no explanation and there were no separate statements or public dissents—which may reflect that there was a consensus among the justices to let the D.C. Circuit (which is set to hear oral argument in Trump’s appeal on January 9) go first. As I’ve suggested elsewhere, whether Friday’s denial is a big deal or not really depends on what happens once the D.C. Circuit rules. It’s distinctly possible that the case could end up back before the justices in a matter of weeks—at which point the decision to sit back for now may not have any significant consequences.

Second, on Wednesday, the Court finally (sort of) acted on the four pending emergency applications asking the justices to block the Biden administration’s “Good Neighbor” ozone pollution rules. In an unsigned order, the Court deferred resolution of the applications (which have already been pending for two months) pending oral argument during the Court’s February 2024 sitting. Holding oral arguments on emergency applications (that is, without taking up the full appeal) are quite rare; this will be only the third the Court has held since 1971 (the first two coming in January 2022 in the OSHA vaccination-or-testing and CMS vaccine mandate cases). And given that no further briefing is expected, the fact that the Court is not setting these arguments for February may be a clue that the justices expect to have other … more urgent … matters to attend to in January.

The Court did not rule on the two pending applications asking the justices to un-block those parts of Idaho’s abortion ban that a district court had frozen, after it held that the medical exception in the ban was narrower than (and thus preempted by) EMTALA—the federal statute that requires all medical facilities receiving Medicare funds to provide stabilizing treatment to any and all emergent patients. It is possible that the Court will rule on them this week, but given that the applications have both been fully briefed since November 30, it’s not obvious what urgency would lead the Court to issue a decision now but not earlier.

Other than that, nothing is expected from the Court this week. To preserve the stay of the Colorado Supreme Court’s decision, former President Trump has to file his cert. petition seeking review of that ruling by next Thursday (January 4). Even if he files this week, the Court won’t act on the petition at least until the plaintiffs file their response. So perhaps everyone at One First Street will be able to exhale, at least temporarily, during the holiday break.

Finally, in recent years, the Chief Justice has made it a habit of releasing his “Year-End Report” at 6:00 p.m. (ET) on December 31. If that pattern holds, it should post to this page on the Supreme Court’s website right around then.

The One First “Long Read”: When Justice Davis Was Picked To Decide an Election

The specter of the Supreme Court once again being in a position to resolve cases with potentially outsized impact on the presidential election has drawn a lot of comparisons to the Court’s December 2000 ruling in Bush v. Gore—including in this New York Times op-ed by me and Steven Mazie, who covers the Court for The Economist. But Bush v. Gore was not the first time members of the Court were in the middle of resolving a presidential election. That episode, and the sobering lessons it continues to provide, arose out of the disputed Election of 1876.

To make a very long story short(er), the 1876 presidential election was not just close; it was controversial in any number of respects. The rise of white supremacist violence in the South led to widespread reports of voter intimidation, fraud, and other mischief at the polls, the result of which was that returns from three states (Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina) were disputed. And one elector from a fourth state (Oregon) was challenged on the ground of constitutional ineligibility (because he held a federal office as postmaster). Without those 20 electoral votes, the Democratic nominee, New York Governor Samuel Tilden, had 184 electoral votes—one shy of the 185 he needed for a majority and victory.

But with the House of Representatives controlled by Democrats and the Senate controlled by Republicans, there was an impasse. Republicans, through their control of the Senate, claimed that they had the power to simply count the disputed electors for their nominee, Ohio Governor Rutherford B. Hayes. Democrats, through their control of the House, claimed that they’d be able to resolve the election through the procedure spelled out by the Twelfth Amendment—with the House voting by state delegation. Prior to the passage of the Electoral Count Act of 1887 (which was itself a response to the 1876 morass), both sides had at least superficially plausible arguments, leading to the very real specter of a constitutional crisis where the House and the Senate picked different presidents.

Ultimately, the compromise that was reached was to create a commission to resolve the provenance of the 20 disputed electoral votes (and, thus, the election). The 15 members would include five members of the House; five senators; and five Supreme Court justices. And the recommendation of the commission would stand unless both chambers of Congress overrode it. It was understood that seven of the members would be Republicans; seven would be Democrats; and the 15th would be Justice David Davis.

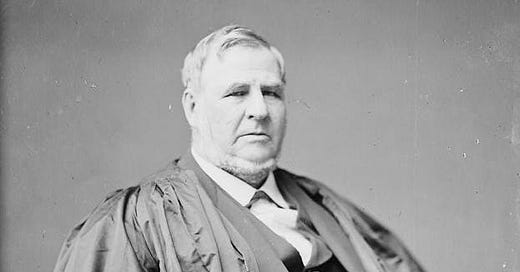

Davis, who made his name as a state circuit judge in Illinois (where, among other things, he had become close friends with a local lawyer named Abraham Lincoln), had been appointed to the Supreme Court by Lincoln in 1862 after helping to run Lincoln’s presidential campaign in 1860. But despite his close friendship with Lincoln, Davis was fiercely independent in his politics. (Indeed, his most famous opinion during his tenure on the Court, in Ex parte Milligan, harshly and unflinchingly repudiated his dear friend’s misbegotten experiment with military tribunals during the Civil War.) It wasn’t just that Davis was independent; it was that he had a reputation in Washington for being equal parts unpredictable and incorruptible. As Roy Morris wrote in 2003, “no one, perhaps not even Davis himself, knew which presidential candidate he preferred.” By having Davis in the position of casting what would likely be the decisive vote, congressional Democrats and Republicans could be confident that neither party would have an unfair advantage on the commission.

The plan might have worked, too, had it not been for Democrats in the Illinois state legislature. In a transparently clumsy effort to nudge Davis toward Tilden, they elected Davis to the open Senate seat from Illinois. The move promptly backfired; Davis refused to serve on the commission—and, shortly thereafter, resigned from the Court so he could fulfill his obligation to the Illinois legislature by serving in the Senate.

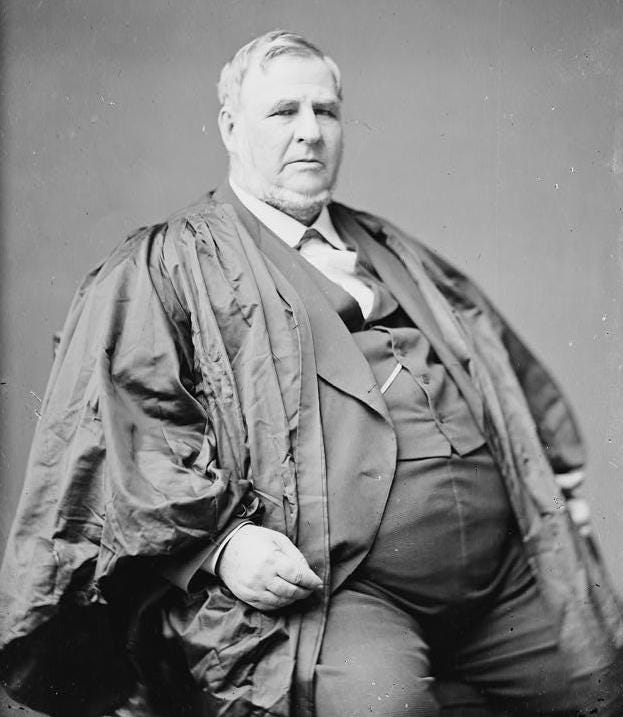

With Davis no longer available, the four other justices on the commission picked their Republican colleague, Joseph Bradley, who had been appointed to the Court by President Grant in 1872. And with Bradley voting in line with the other seven Republican members of the commission, the commission ultimately voted, 8-7, to recommend awarding all 20 disputed electors—and, with them, the election—to Hayes. As it turns out, that still wasn’t quite enough; although Democrats couldn’t override the commission (only both chambers, acting together, could), they tried to delay matters and potentially run out the clock. Ultimately, as the story goes, Hayes agreed to what’s now known as the “Compromise of 1877,” including the withdrawal of federal troops from the South and the effective end of Reconstruction, in exchange for Democrats acceding to the commission’s recommendations. At 4:10 a.m. on March 2, 1877 (two days before inauguration day), Congress declared Hayes the winner of the Election of 1876.

The 1876 experience prompted a series of reforms, culminating in the Electoral Count Act of 1887 (about which we learned … so much … after the Election of 2020). But as much as we still talk about those reforms, we’ve lost sight of the role that Justice Davis almost played. In a moment of high political drama and national tension, Democrats and Republicans were able to agree on one thing: that there was a Supreme Court justice with enough integrity, independence, and credibility across both parties that he could be trusted (more than anyone else, anyway) with what would effectively be a decisive vote in a presidential election. Had it worked out as planned, Justice Davis might be much better-known today.

SCOTUS Trivia: Justices in Congress

Davis is one of 32 justices across the Court’s history who also served in the U.S. Congress. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he is the only one of those 32 who served in the legislature after his tenure on the Court.

The last justice to have also served in Congress was Justice Hugo Black (who had been a Senator from Alabama from 1927 to 1937, and did not retire from the Court until 1971). Technically, the last justice appointed to the Court with prior congressional experience was Justice Sherman Minton, who was appointed in 1949 (12 years after Black) after an earlier stint as a Senator from Indiana, during which he also served as Senate Majority Whip.

Minton was the 87th person appointed to the Court. Thus, after 31 of the first 87 justices (35.6%) had some form of congressional experience prior to joining the Court, none of the subsequent 29 have had the same.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one. This week’s bonus issue (the December installment of “Karen’s Corner,” this time for real) will drop Thursday morning. And we’ll be back with a regular issue next Monday.

Happy Monday, everyone—and, to those who celebrate, Merry Christmas! I hope that you have a great week.

I was not expecting an essay on Christmas Day but I did enjoy reading it. Too bad some of today's Supreme Court justices aren't able to channel Justice Davis' integrity.

The Sherman Minton Bridge is an important one in my home town of Louisville, connecting across the Ohio River to Indiana.