58. Congress Quietly Expands the Supreme Court's Jurisdiction Over Courts-Martial

A little-noticed provision of the FY2024 National Defense Authorization Act closes a loophole in the justices' ability to review military convictions, but it may make little practical difference

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

I already covered most of last week’s big developments in last Thursday’s bonus issue. In addition to agreeing (very quickly) to expedite a petition for certiorari “before judgment” by Special Counsel Jack Smith in the January 6-related prosecution of former President Donald Trump, the Court also granted a bunch of cases on Wednesday—including a case about the scope of the criminal charge that has been used perhaps most widely against lower-level January 6 defendants. The justices also agreed to take up two petitions challenging lower-court rulings that would significantly curtail nationwide access to mifepristone (which are on hold thanks to a stay the Court entered back in April). Tellingly, the Court did not grant the plaintiffs’ “cross-petition” in the mifepristone case1—which means that the FDA’s original 2000 approval of mifepristone won’t be before the justices, and which likely signals that the Court is focused on whether the plaintiffs have standing in the first place. In other words, this case is likely not going to be a referendum on access to mifepristone by the time the Court rules next summer. The Court on Thursday also turned away an emergency application seeking to block Illinois’ assault weapons ban, with no public dissents.

Although the week before Christmas is usually pretty quiet at the Court, this week is shaping up to be … anything but. Later today, the Court will host a private ceremony in memory of Justice O’Connor, followed by the late Justice lying in repose in the Great Hall from 10:30 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. Former President Trump’s response to the petition for cert. before judgment in the January 6 case is due Wednesday by 3:00 ET (perhaps portending a ruling granting or denying the petition by the end of the week). And the Court is still sitting on four emergency applications asking the justices to block the Biden administration’s “Good Neighbor” pollution rules and two emergency applications seeking to put back into effect those parts of Idaho’s abortion ban that a district court had blocked on the ground that they likely conflict with EMTALA (the federal statute requiring hospitals receiving federal funds to provide stabilizing medical care to emergent patients regardless of their ability to pay for those services).

There’s no guarantee that we’ll get any of these rulings this week. But the justices don’t like working over the holidays any more than the rest of us, so…

The One First “Long Read”:

Congress Closes a Certiorari Loophole

A number of media outlets flagged last week that Congress had reached an agreement on the FY2024 National Defense Authorization Act—the annual “must-pass” military funding bill onto which lots of other significant national security-related statutes tend to be tacked (including, this year, a four-month extension of section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act—which was set to expire on December 31 and will now sunset on April 19, 2024).

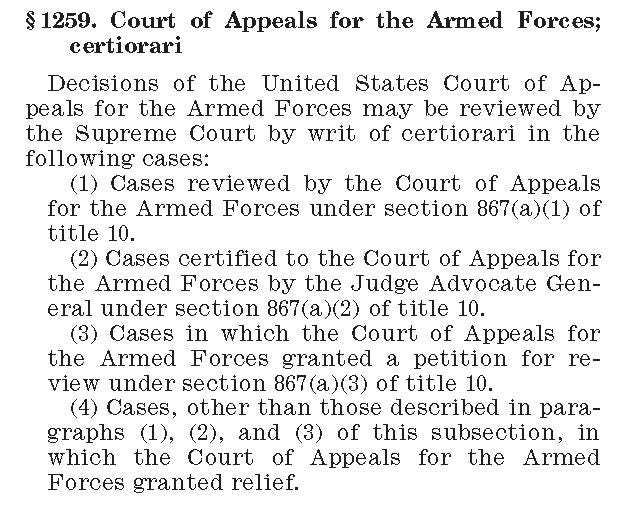

But no one in the media appears to have noticed that one of the provisions in the 973-page bill would also reform the Supreme Court’s statutory jurisdiction over courts-martial—so that the justices’ ability to review a military conviction will no longer depend upon whether the Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces (CAAF) had itself chosen to hear that case. This development is one that a bunch of folks (including me and my friend and occasional co-counsel Gene Fidell) have long been arguing for. And it’s a useful reminder of the extent to which Congress can regulate the Court’s docket—if it wants to. But whether the reform will actually have any real effect once it enters into force (starting one year from when President Biden signs the bill into law) is ultimately going to be up to the justices—who have shown a troubling lack of interest in even those military appeals over which they already had statutory jurisdiction.

I’ve told most of this story before, but just as a refresher, when Congress first provided for appellate review of military convictions in the Uniform Code of Military Justice in 1950, it left the Article I Court of Military Appeals (today’s CAAF) as the last word in such cases. The Supreme Court could hear challenges to courts-martial, but only through habeas petitions collaterally attacking military convictions (in which the civilian courts’ review was heavily circumscribed), not as direct appeals in which any and all legal claims could be considered de novo.

In 1983, Congress for the first time gave the Supreme Court the power to review CAAF via certiorari—but only in specific cases: when CAAF’s jurisdiction was mandatory (i.e., capital cases and government appeals) and in those other cases in which CAAF chose to grant a discretionary petition for review by a servicemember or otherwise “granted relief.” In other words, a servicemember challenging a non-capital conviction could only ask the Supreme Court to take up their appeal if CAAF first exercised its discretion to hear the case.

At the time, conditioning the Supreme Court’s power on CAAF’s discretion was justified by the Justice Department as protecting the Supreme Court’s docket—on the theory that CAAF would thus serve as a gatekeeper for frivolous (or, at least, patently meritless) appeals at a time when the justices were resolving more than 150 cases every term.

But as Gene Fidell and I wrote in a 2019 New York Times op-ed, whatever the merits of that justification in 1983, it has been overtaken by two subsequent events: First, in 1988, Congress gave the Supreme Court near-plenary control over its docket—thereby vitiating the docket-management concerns on which the Justice Department had relied in 1983. In a world in which the justices control just about all of their docket, having that discretion extend to one more category of appeals does not exactly seem like a huge imposition. Second, over time, CAAF has become an increasingly stingy gatekeeper—granting a decreasing percentage of discretionary petitions for review (down to somewhere around 10%), and regularly denying petitions in cases with at least a decent chance of attracting the Supreme Court’s attention. Making matters worse, the Justice Department has taken the position in litigation that, even when CAAF does grant discretionary review, the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction is limited to the specific issues on which CAAF granted review (and not to other matters in the case). As Gene and I summarized in 2019:

The result of these developments is that only a tiny minority of service members convicted by court-martial are entitled to appeal their conviction to the Supreme Court. In that regard, service members are not only treated worse than every other criminal defendant in state and federal courts, they’re also treated worse than the non-citizen enemy combatants being tried at Guantánamo.2

Congress has, finally, taken heed. Section 533 of the FY2024 NDAA is not exactly a model of clarity. But at its core, it gives the Supreme Court power to review cases in which CAAF has not just granted a petition for review or “other relief,” but in which it has “refused to grant” a petition for review or “other relief.” In other words, servicemembers must still exhaust CAAF’s discretionary jurisdiction, but a denial by CAAF will not foreclose the Supreme Court’s ability to review the servicemember’s appeal via certiorari. Thus, a servicemember with a cert.-worthy issue no longer needs to rely upon a discretionary action by CAAF in order to get before the Supreme Court; he can file a cert. petition like any other criminal defendant in the country.

This expansion of the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction won’t go into effect immediately. Under section 533(b), it applies only to decisions (granting or denying review) by CAAF that are at least one year after the FY2024 is signed into law. So servicemembers whose appeals are currently pending, or are rejected by CAAF within 365 days of when President Biden signs the NDAA into law, won’t be able to take advantage of this new language. But starting in roughly a year, a decision by CAAF to deny discretionary review will no longer be an independent bar to a servicemember seeking review from the Supreme Court.

That’s the good news—and it is good news. The harder question is whether this reform will make any difference on the justices’ side. As I explored in detail back in January, the justices have granted a remarkably small number of petitions from CAAF in the 40 years that they have had the power to do so. And that’s even though there have been a number of compelling cases for the Court’s intervention. Examples abound, but an obvious one is the Court’s refusal to review a 2015 CAAF decision that identified a conflict between two Supreme Court decisions—a 1996 case about the military death penalty and a 2002 decision involving Arizona’s—that only the justices could resolve. Indeed, the Court has conducted plenary review of only a single post-conviction appeal by servicemembers since 1996 (versus a handful of appeals by the government). Folks may disagree about which cases the justices should have taken but didn’t; what can’t be denied is that there have been a raft of cert.-worthy issues on which the justices have given CAAF the last word.

Part of the issue now is that at least two justices—Justices Alito and Gorsuch—appear to believe that the Court can’t constitutionally review CAAF, per Justice Alito’s dissenting opinion in Ortiz v. United States.3 Unless they’re going to acquiesce in the Court’s 2018 holding to the contrary in Ortiz,4 that means that servicemembers may need to persuade four of the seven justices who think that such jurisdiction is constitutional.

Lest this seem like an academic issue, the Court currently has before it a pair of cert. petitions asking the justices to resolve whether, after and in light of the Court’s 2020 ruling in Ramos v. Louisiana, court-martial convictions must also be unanimous. (Under current law, non-capital convictions in a general court-martial can be imposed by a 6-2 or 7-1 vote.) I’m a little biased (I’m counsel of record on one of the petitions), but given the gravity of the question, and given the … breezy … analysis CAAF deployed in answering it earlier this year, this ought to be the kind of question that merits the justices’ review. Otherwise, that will be yet another sign that the Court is willing to let CAAF have the last word even on constitutional questions—so long as those questions affect only servicemembers. In those circumstances, Congress finally closing the 40-year-old loophole in 28 U.S.C. § 1259 may end up being little more than an empty gesture.

SCOTUS Trivia: The Last Time Congress Expanded the Court’s Certiorari Jurisdiction

Although readers of this newsletter and/or those familiar with the Court’s history will know that the last significant reform to the Supreme Court’s certiorari jurisdiction was in 1988—when Congress dramatically expanded the Court’s discretion over state court decisions and all-but eliminated mandatory appeals in such cases.

But since 1988, Congress has expanded the Supreme Court’s certiorari jurisdiction on three other occasions: In 2004, when the Supreme Court gained the power to directly review by certiorari decisions of the Supreme Court of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands; in 2006, when the Court gained the power to directly review by certiorari decisions of the Supreme Court of Guam; and in 2012, when the Court gained the power to directly review by certiorari decisions of the Supreme Court of the Virgin Islands. After their creation, they each had a probationary period during which their decisions were reviewable via certiorari in their respective court of appeals. But as those periods expired (or were truncated by Congress), the U.S. Supreme Court gained the power to review them directly.

Near as I can tell, the next petition the Court grants to review one of these territorial supreme courts will be the second. The only apparent exercise of plenary review over one of the three to date was the Court’s 2007 review of the Guam Supreme Court in Limtiaco v. Camacho.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one. This week’s bonus issue (the December installment of “Karen’s Corner”) will drop Thursday morning. And we’ll be back with a regular (Christmas) issue next Monday.

Happy Monday, everyone. I hope that you have a great week!

A “cross petition” can arise from a lower-court ruling that issued a mixed verdict. Where Party A seeks review of an issue on which it lost, Party B may file a “cross petition” asking the justices to review the issue on which it lost, either “conditionally” (that is, only if the Court grants Party A’s petition), or independently. In the mifepristone case, the plaintiffs were seeking review of the Fifth Circuit’s reversal of Judge Kacsmaryk’s invalidation of the FDA’s 2000 approval of mifepristone—the main issue on which the FDA and Danco Laboratories had prevailed.

Under the Military Commissions Act, A defendant convicted by a Guantánamo military commission may take an appeal as of right to the Article I Court of Military Commission Review; from there as of right to the D.C. Circuit; and from there via certiorari to the Supreme Court.

Disclosure: I was counsel for the petitioner in Ortiz.

In United States v. Briggs (in which I represented two of the respondents), Justice Alito wrote the majority opinion in a case in which the Court reversed CAAF, without noting his dissent in Ortiz. Justice Gorsuch concurred in the Court’s reversal of CAAF because, in his words, “a majority of the Court believes we have jurisdiction, and I agree with the Court’s decision on the merits.” Whether that means Justice Gorsuch will reach the merits in future appeals from CAAF remains to be seen.

The parallels to HamdanvRumseld are everywhere. As a DCCircuit judge, John Roberts had overturned the habeas petition/grant of a non-citizen "enemy combatant" held at Guantanamo. (An earlier case, Hamdi, involved a US citizen.) According to Roberts, the Geneva Conventions apply only to nations, not to individuals, though I'm not even certain what that means. Suffice to say that if I were an Afghan citizen or a pregnant woman or a soldier falsely accused, I'd swallow the hemlock before placing my fate in the hands of John Roberts.

Any advice or guidance on who one would contact with an OVERWHELMING amount of evidence:

1. that a ‘person’ Knowingly and Willfully was untruthful not only in 5+ separate legal tribunals, but including testimony in front of the US Supreme Court?

(Relevant due to a linked UCMJ case.)