56. Justice O'Connor's Complexities

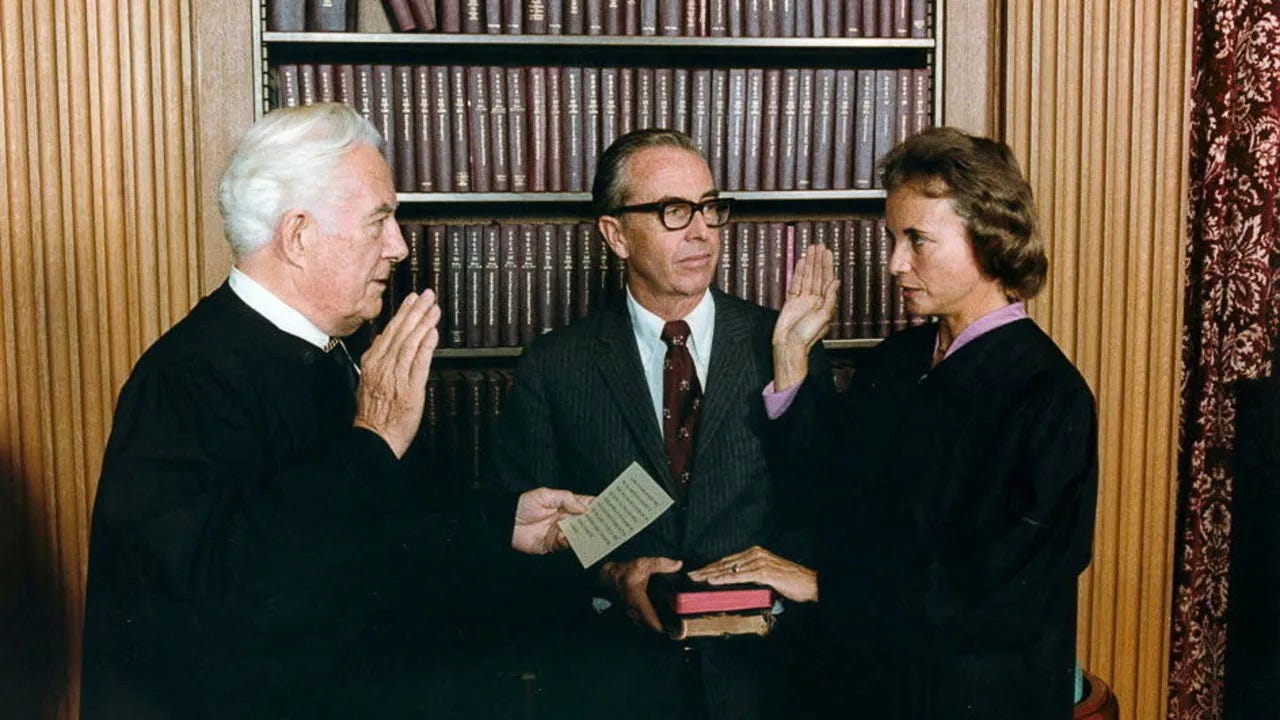

The death of the first woman to serve on the Court raises challenging questions about how we assess justices' legacies—and how difficult it is to disentangle them from subsequent events

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it with your networks (and subscribing if you don’t already). And I hope you’ll consider upgrading to a paid subscription if your circumstances permit (and if you haven’t already!):

On the Docket

Obviously, the biggest news from last week came Friday morning—when the Court announced the death of retired Justice Sandra Day O’Connor at the age of 93 from complications arising out of her long battle with dementia. More on that below.

Before that, the only real news to come out of the Court were two denials of emergency relief over no public dissents; and a series of stories recapping the first week of the December argument calendar (including the justices’ surprising focus on the Seventh Amendment issue in SEC v. Jarkesy, about which more in a future issue). Among other things, this meant that there was still no ruling from the justices on the four pending emergency applications challenging the Biden administration’s “Good Neighbor” pollution rules, which have been ripe for decision now for more than a month.

This week is shaping up to be a bit different. In addition to a regular Order List at 9:30 ET today (which will likely include grants of review, including perhaps in some high-profile cases), and in addition to the second week of the December argument calendar (starting at 10:00 ET today), the Court’s website suggests that one or more opinions in argued cases are expected at 10:00 ET tomorrow—the first decisions from the Court during the current term. Historically, it wasn’t at all unheard of for the Court to hand down at least a handful of merits decisions in December. Last term was an aberration, with the first such ruling not coming until January 23, so perhaps this augurs something of a return to the mean. (As for which ruling(s) is/are coming down tomorrow, <insert shrug emoji>.)

All of which is to say, expect a fair amount of Supreme Court news in the next few days.

The One First “Long Read”: Justice O’Connor’s Legacy

The very last decision in which Justice Sandra Day O’Connor participated before retiring from the Supreme Court in January 2006 was Central Virginia Community College v. Katz—an outwardly technical dispute over whether Congress had the power, as part of its authority over federal bankruptcy law, to treat non-consenting states as ordinary judgment creditors (i.e., to abrogate those states’ sovereign immunity by requiring them to potentially take a haircut on debts owed to them by debtors in bankruptcy). In a 5-4 decision written by Justice Stevens, the Court answered that question in the affirmative.

What is striking about Katz is not its common sense bottom line, but how radically at odds it was with the previous 11 years of the Court’s sovereign immunity jurisprudence. Starting in Seminole Tribe of Florida v. Florida, the Court had spent the previous decade holding, in case after case, that Congress had no power to subject non-consenting states to suit through any of its Article I powers—a controversial expansion of state immunity in which virtually every decision featured the same 5-4 split (with Rehnquist, O’Connor, Scalia, Kennedy, and Thomas in the majority, and Stevens, Souter, Ginsburg, and Breyer in dissent). Only one justice switched sides1 in Katz—Justice O’Connor. But despite her impossible-to-miss volte face, she didn’t write separately. Instead, she joined Justice Stevens’s majority opinion (and its … debatable … distinguishing of those prior precedents) in full.

It was a maddening switch—calling into question one of the central principles upon which the Court’s recent foray into state sovereign immunity had been based (a foray in which she had been a regular participant), and opening the door for further inroads. For those who agreed with the earlier decisions, the unexplained departure was maddening. For those who disagreed with them, the refusal to expressly repudiate them was maddening.

But it was also profoundly pragmatic; barring Congress from requiring states to take haircuts in bankruptcy proceedings would have massive (and messy) ramifications for bankruptcy law, whereas allowing it to do so kept the trains running as they had for decades. It may not have been consistent with the theory animating the Court’s prior state sovereign immunity cases, but so what? Better for the Court to stick to a theory that might have been wrong and that was producing problematic effects as applied in this context, or better for it to just come out a different way in a different case? For O’Connor, that question appeared to answer itself.

I keep coming back to Katz when trying to figure out what to say about Justice O’Connor’s legacy. A lot of it has already been said through a flood of tributes from the justices themselves; from some of her former clerks; and even from folks who have, in the past, been critics of hers (and still are, thanks to her role in Bush v. Gore; her massively important role in narrowing the scope of post-conviction habeas corpus; and her consistent votes, until Katz anyway, for the major cases in the Rehnquist Court’s invigoration of an especially contested vision of federalism). The hard part is reconciling the Justice O’Connor who did at least some things that likely alienated everyone (even if it was different things for different audiences) with the Justice O’Connor who was nevertheless both a vital trailblazer and a justice who had, in the main, a more modest view of the Court’s role vis-à-vis the other institutions of government than most of her colleagues.

A few years ago, I wrote a short review of Evan Thomas’s truly wonderful biography of Justice O’Connor (one of my holiday book recommendations from last year) that tried to reflect on the tension inherent in O’Connor’s legacy: a justice whose voice was a moderating one even if some of her votes supported rulings that were anything but:

it is impossible not to notice the absence of more moderate voices on the Court. . . . In the process, the Court has come to resemble the country—two deeply entrenched blocs, each having a hard time seeing the arguments and principles that define the other side. . . . These developments would not have sat well with O’Connor, a Justice for whom “[c]ivility, not snark, was the currency of discourse. Extremism of any kind was to be avoided. Absolutism was for demagogues.”

. . . . [I]t is hard to imagine a scenario in the near or medium term in which it will be in any President’s political interest to try to bridge that gap, rather than appointing the most ideologically extreme candidate capable of gaining Senate confirmation. O’Connor may have been “First,” but Thomas’s book all but hits readers over the head with the troubling specter that she might also have been the last of her kind. Her colleagues knew it, too. In a note to the Justice shortly after she announced her retirement in August 2005, Justice Scalia wrote that she had been “the forger of the social bond that has kept the Court together.” He wondered, “who will take that role when you are gone?” Fourteen years later, that question remains unanswered.

To that, I’d add just one last point: Just about anyone who follows the Court knows that Justice Alito currently sits in Justice O’Connor’s seat. But we may not all remember that Alito was President George W. Bush’s third choice to replace the Court’s first woman. When O’Connor initially announced her plans to retire at the end of the October 2004 Term, Bush nominated then-D.C. Circuit Judge John Roberts to her seat. Roberts was only nominated to succeed Chief Justice Rehnquist after Rehnquist succumbed to throat cancer that September. And Bush’s second choice for O’Connor’s seat was his longtime friend and White House Counsel Harriet Miers—whose nomination was torpedoed largely through pressure from the right, not from the left. Had either Roberts or Miers ended up in O’Connor’s seat, it’s entirely possible that we would look at her legacy quite a bit differently, all the more so if the Court hadn’t moved so sharply to the right over the last five years.

Sometimes, fairly or not, a justice’s legacy is going to be defined by events that don’t just post-date their tenure on the Court, but that are, in many cases, completely beyond their control. Evan Thomas referred to O’Connor as someone who is “easy to caricature and harder to understand.” In that respect, perhaps the best we can do to respect her legacy is to remember the increasingly forgotten virtues of moderation, compromise, and civility to which she aspired—even if, sometimes, she honored them in the breach.

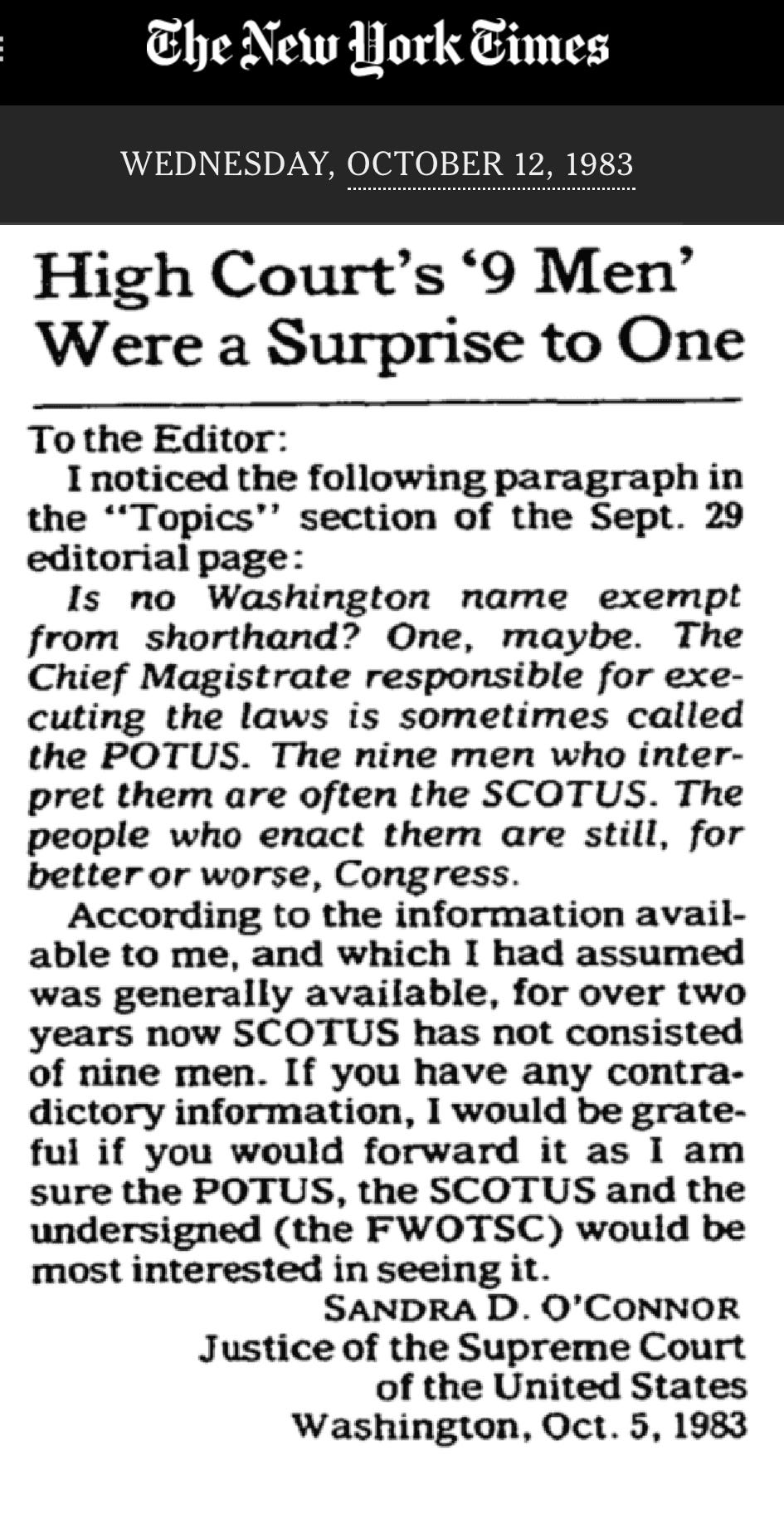

SCOTUS Trivia: The FWOTSC, She Writes

With a hat tip to Professor Marin Levy, this one speaks for itself:

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one. This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning. And we’ll be back with a regular issue next Monday.

Happy Monday, everyone. I hope that you have a great week!

Chief Justice Roberts had replaced Chief Justice Rehnquist in the interim; the other seven justices were all on the same side in Katz as in the earlier cases.

The NYTimes clip is hilarious. Great content