55. The Lockwood Bill and the Supreme Court Bar's Glass Ceiling

It took an Act of Congress, but 143 years ago this week, Belva Lockwood became the first woman to argue a case before the Supreme Court

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it with your networks (and subscribing if you don’t already). And I hope you’ll consider upgrading to a paid subscription if your circumstances permit (and if you haven’t already!):

On the Docket

With a short week due to Thanksgiving, there wasn’t much that came out of the Court over the past seven days. The Court issued a regular Order List on Monday that included the addition of three total cases (two of which were consolidated) to the argument slate for later this term. And Justices Thomas and Kavanaugh dissented from the Court’s denial of certiorari in E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co. v. Abbott, with Justice Thomas filing a solo opinion objecting to the use of “nonmutual offensive collateral estoppel” against defendants in multi-district litigation.1

If anything, the real news was the absence of news. The Court now has an accumulating backlog of “relists”—cases that the justices have considered at multiple Conferences in which someone may be writing a dissent or there may be maneuvering behind the scene before the Court decides whether to take up the dispute. And there are seven pending emergency applications—including the four major ones challenging the Biden administration’s “Good Neighbor” pollution rules, which have been fully briefed for 25 days. (I’m starting to wonder if there might be a majority opinion coming down the pike in those.)

Finally, although it doesn’t appear to have been docketed yet, Idaho, represented in part by the Alliance Defending Freedom, has filed an emergency application asking the justices to freeze a lower-court injunction against the state’s abortion ban (the “Defense of Life Act”)—which makes it a crime for a doctor to perform an abortion except when they “determined, in his good faith medical judgment and based on the facts known to the physician at the time, that the abortion was necessary to prevent the death of the pregnant woman.” The federal government sued Idaho, arguing that the state law is preempted by the federal Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA), which requires that emergency room physicians at hospitals receiving Medicare funds offer stabilizing treatment to patients who arrive with emergency medical conditions, whether or not they are life-threatening. (A related dispute over the scope of EMTALA is currently pending in the Fifth Circuit.)

In the Idaho case, the district court sided with the federal government and issued a preliminary injunction against the Idaho law. After a Ninth Circuit panel stayed that injunction, an en banc “panel”2 vacated that stay and ordered expedited oral argument on Idaho’s appeal (currently set for the week of January 22, 2024). Idaho (with ADF) is asking the justices to put Idaho’s law back into effect while its appeal proceeds in the Ninth Circuit. Whatever happens with Idaho’s application, the interaction between EMTALA and state abortion bans seems heading for the Supreme Court one way or the other—and we’ll look at the question more closely in a future issue.

In all, then, it’s likely to be a busy week at the Court, and not just because of the “December” oral argument calendar, which begins at 10:00 this morning.

The One First “Long Read”: The First Woman Admitted to the Supreme Court Bar

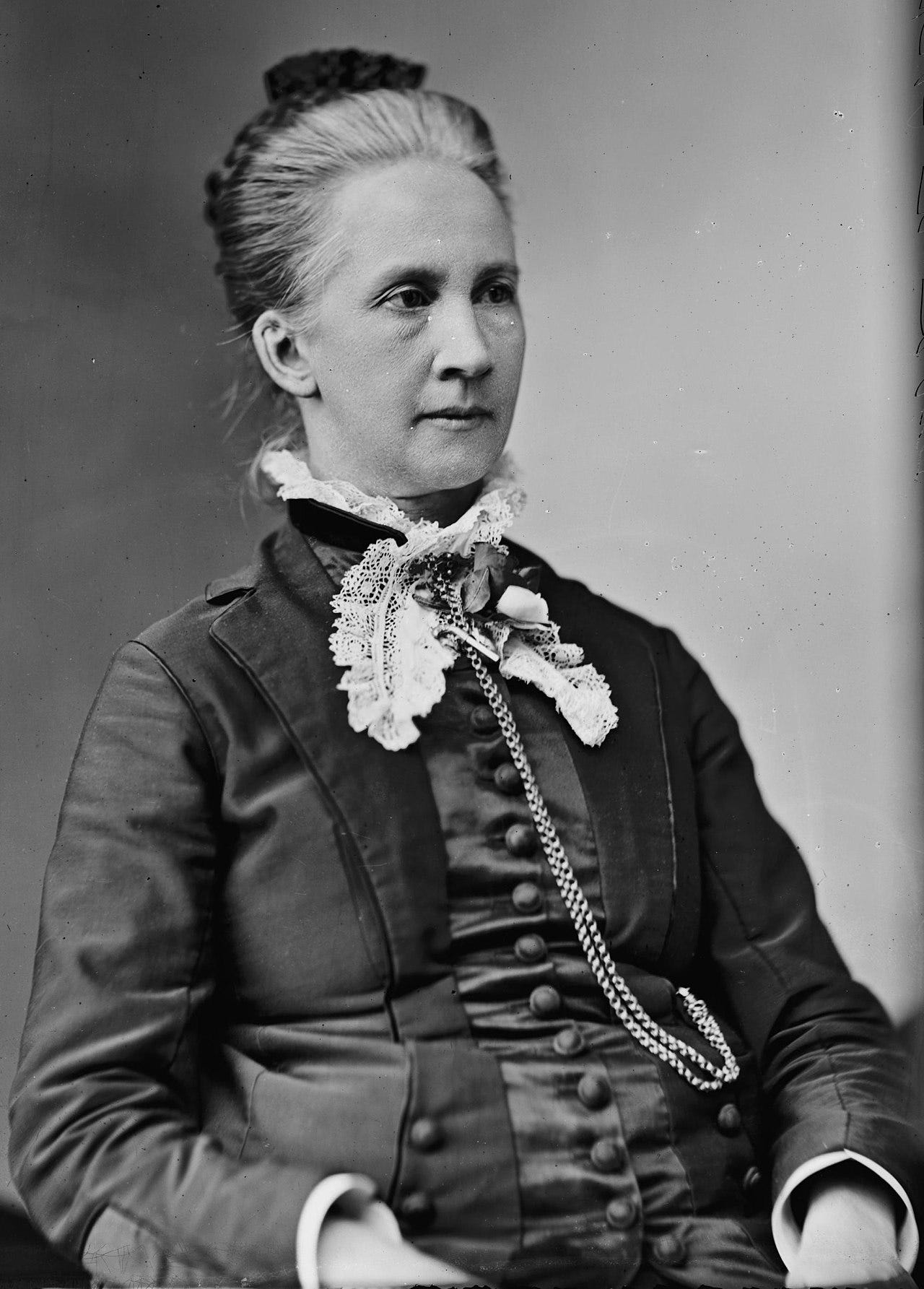

In October 1876, a Washington, D.C. lawyer—Albert G. Riddle—moved the admission to the Supreme Court bar of Belva Lockwood. Lockwood, who had a remarkable life story even to that point, met the relevant qualifications: she had received a law degree (albeit only after a last-minute intervention from President Grant to pressure the law school, of which he served as President ex officio, to confer it) three years earlier, and had been a member of the District of Columbia bar in good standing since. On November 6, 1876, Chief Justice Morrison Waite nevertheless denied Riddle’s motion in open court. According to a contemporaneous newspaper account, Waite announced that:

By uniform practice of the Court, from its organization to the present time, and by the fair construction of its rules, none but men are admitted to practice before it as attorneys and counselors. This is in accordance with immemorial usage in England and the law and practice in all the States until within a recent period, and the Court does not feel called upon to make a change until such a change is required by statute or a more extended practice in the highest courts of the States.

Indeed, the Court had held, three years earlier, in Bradwell v. Illinois, that women did not have a constitutional right to admission to the bar; even three of the justices who had dissented in the Slaughterhouse Cases on the ground that the Constitution conferred a right to pursue a common calling didn’t think that such a right extended to women (and wrote separately in Bradwell to make that point clear, concluding that “[t]he paramount destiny and mission of woman are to fulfill the noble and benign offices of wife and mother.”).3 Now, even though the Supreme Court’s rules did not specifically limit bar membership to men, or expressly exclude women, Chief Justice Waite delivered the Court’s interpretation that they nevertheless prohibited Lockwood’s admission despite her admission to the D.C. Bar.

Lockwood and her supporters responded with a massive, intense lobbying campaign in Congress. Taking Chief Justice Waite up on his invitation, bills were introduced in both chambers of Congress in 1878 and 1879 titled “An act to relieve certain legal disabilities of women.” Finally, on February 15, 1879, President Rutherford B. Hayes signed what was known as the “Lockwood Bill” into law:

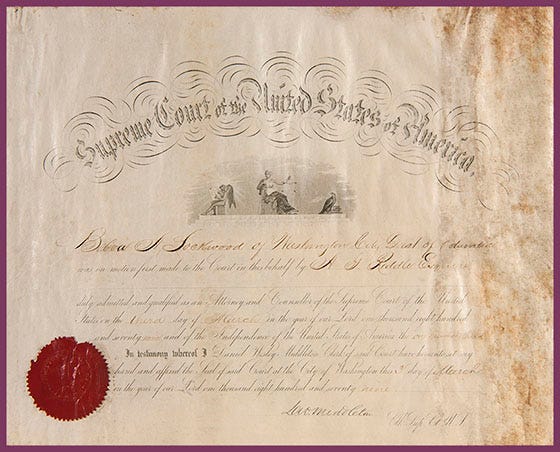

Two and a half weeks later, on March 3, Riddle once again moved Lockwood’s admission. This time, his motion was granted, and Lockwood was sworn into the Supreme Court Bar before a packed Old Senate Chamber.

The Lockwood Bill is fascinating in several respects. Besides its immediate and intended impact, it’s also an interesting separation-of-powers episode—reflecting the apparent assumption by all involved, including the justices, that it was just fine for Congress to dictate to the Supreme Court its own rules of admission. Given contemporary debates over just how much Congress can regulate or otherwise interfere in the Court’s internal operations, it’s a revealing historical precedent that the Court specifically raised the specter of Congress weighing in on the question of admitting women to practice—and then acquiesced in Congress’s answer.4

Lockwood’s admission was not just symbolic. 143 years ago this week—on November 30, 1880—she also became the first woman to argue before the Supreme Court, appearing as co-counsel on behalf of the appellant in Kaiser v. Stickney. Her client, Caroline Kaiser, unsuccessfully contended that she did not have to pay a $16,000 debt (the Court ruled that she did in a decision that does not appear in any published reports). But although Lockwood thereby crashed through the Court’s glass ceiling, it would be a quarter-century before a woman would again argue before the justices—when Lockwood herself would appear once more in the case of United States v. Cherokee Nation. Over the two-day argument in January 1906, Lockwood successfully persuaded the justices to affirm the decision below—which had held that the United States owed the Cherokee Nation over $5 million under an 1835 treaty.

Lockwood was soon followed to the lectern by Lyda Burton Conley, Ellen Spencer Mussey, and Sarah Herring Sorin, but it wouldn’t be until the 1920s—when women first began regularly appearing before the Court on behalf of the federal government—that the presence of women at the Court’s lectern would become more than an annual occurrence. (As Marlene Trestman has painstakingly documented, four women who spent time as Justice Department lawyers—“the fabulous four,” Mabel Walker Willebrandt, Beatrice Rosenberg, Bessie Margolin, and Helen Carloss—accounted for roughly half of all Supreme Court arguments delivered by women advocates through the mid-1960s, with future Judge Constance Baker Motley right behind them.)

Still, women appearing before the Supreme Court remained the exception for a distressingly long period of time (and, I think it can fairly be said, still happens with insufficient frequency today). Willebrandt’s 29 arguments would remain the record for women until it was surpassed by Lisa Blatt in January 2011. Only two other women have since passed Willebrandt—(now D.C. Circuit Judge) Patricia Millett, who also briefly passed Blatt in the early 2010s before Blatt re-claimed the record that she still holds, and Nicole Saharsky. It wouldn’t be until 1955 that women would argue against each other in the same case. And still today, only 35 of the 153 lawyers who argued before the Court during the October 2022 Term (22.9%) were women. Suffice it to say, there’s still work to be done. Or as Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote in a foreword to Professor Jill Norgren’s biography of Lockwood, “With optimism and tenacity, may we continue to strive as she did to advance our Nation and World the ideals of liberty, equality, and justice for all.”

SCOTUS Trivia: Madame Solicitor General

I’ve told this anecdote before, but it seemed entirely appropriate to rehash it given today’s “long read”: When she became the first woman to serve as Solicitor General of the United States in 2009, now-Justice Elena Kagan had one tradition from which she wanted to depart: Instead of appearing before the justices in the “morning dress” that remains the traditional attire of male lawyers appearing on behalf of the federal government (in her words, the women’s version looked “ridiculous”), Kagan appeared in conventional business attire after having “made discreet inquiries” of the Court to ensure that she’d cause no umbrage by doing so. Ever since, as a DOJ spokesperson explained at the time, “the men in OSG will continue to wear [morning dress], as will whichever women choose to wear it.”

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning. And we’ll be back with a regular issue next Monday—by which point I suspect that, if nothing else, there will be decisions on some of the emergency applications discussed above to parse.

Happy Monday, everyone. I hope that you have a great week!

“Collateral estoppel” is the legal principle that, once questions of fact have been conclusively resolved in Case 1, they should not be subject to re-litigation in a future dispute between the same parties. And “offensive non-mutual collateral estoppel” is the application of that principle to prevent the defendant in Case 1 from relitigating a factual issue on which it lost in Case 1 in a future suit by a different plaintiff.

Unlike the other 12 federal circuit courts of appeals, when the Ninth Circuit rehears a matter “en banc,” it still does not sit as a full court (which would be quite a logistical challenge, given that it has 29 active judges). Instead, 10 judges are drawn at random to join the Chief Judge on an 11-judge “mini en banc” panel, which has all the same power as the full en banc court would. There’s also a procedure for “full” en banc review, but it has never been successfully invoked.

In 1892, Bradwell would become the 10th woman admitted to the Supreme Court Bar.

I’m grateful to Professor Will Baude for this point—and for bringing the Lockwood Bill to my attention.

Thanks, Steve, for your terrific article and for acknowledging my work to identify all women who have presented argument at SCOTUS! It's time for me to update the list!! Cheers.

If the current percentage of women arguing before the Supreme Court is too low, what is the right percentage and why?