54. The Politics of the Justices' Pensions

From Reconstruction through the New Deal, Congress regularly used its power over the justices' pensions to incentivize or restrict judicial departures—and to otherwise exert leverage over the Court

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it with your networks (and subscribing if you don’t already). And I hope you’ll consider upgrading to a paid subscription if your circumstances permit (and if you haven’t already!):

On the Docket

Obviously, the big news out of the Court last week was the justices’ adoption of a new “Code of Conduct.” I wrote about the Code of Conduct in detail, both in a CNN op-ed and in last Thursday’s bonus issue, and won’t rehash those takes here. Suffice it to say, it’s hard to see last Monday’s development as the end of the story when it comes to ethics and the Supreme Court.

Perhaps because of the Code of Conduct, it was otherwise a pretty quiet week for the Court—at least until Thursday. Then, the justices handed down a slew of orders on emergency applications on Thursday afternoon—four of which denied two pairs of applications to stay executions in Alabama and Texas (over no public dissents). But the biggest headline was the denial of Florida’s request to un-block its “anti-drag” bill. Justices Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch noted that they would’ve granted emergency relief (albeit without any explanation as to why). And Justice Kavanaugh, joined (except in footnote 1) by Justice Barrett, wrote to stress that he was denying emergency relief because, at a minimum, the ground on which Florida sought emergency relief (that the injunction was too broad—not that it was erroneously imposed in the first place) was one on which the Court was unlikely to grant certiorari. In other words, the Kavanaugh/Barrett statement appears meant to emphasize that their vote to deny relief doesn’t express a view, one way or the other, on the underlying First Amendment questions implicated by anti-drag bills like Florida’s; those remain very much unsettled.

The Court also released the calendar for its January 2024 argument session. The headline of that fortnight is almost certainly the back-to-back arguments on January 17 in two cases asking the justices to overrule their 1984 decision in Chevron—which holds that, where an executive branch agency’s interpretation of an ambiguous statute that it administers is “reasonable,” its interpretation should control. We’ll have more to say about Chevron (and its interplay with the “major questions doctrine”) in the run-up to those arguments.

We expect a regular Order List from the Court (including additional possible grants of certiorari) at 9:30 ET today. The only other matter on which we might hear this week is with respect to the four pending emergency applications challenging the Biden administration’s “Good Neighbor” pollution rules. Those have been fully briefed for some time, so a decision could come this week—or not.

The One First “Long Read”: Judicial Retirements and the Separation of Powers

When Justice Stephen Breyer announced his departure from the Supreme Court in January 2022, his letter explained that he would be retiring from “active service” on the Supreme Court, and would “serve under the provisions of 28 U.S.C. § 371(b)”—as a “retired justice.” Since 1937, Congress has allowed justices who meet certain age and service-duration thresholds to “retire” from the Court, rather than resign—a status in which, in exchange for being available to exercise limited judicial duties (on the lower courts), the justice continues to receive the same salary as they did while “active,” a salary that, arguably (more on this below), is protected from diminution by the Constitution itself.

But the road to 1937 was much more complicated—and, from a separation-of-powers perspective, much more interesting. Congress didn’t provide for any kind of judicial pensions prior to the Civil War. It was only in the late 1860s that the Radical Republicans in the Reconstruction Congress stepped in—in an effort to both respond to the evident incapacity of two of the Court’s eight justices (Robert Grier and Samuel Nelson) and to clear the way for the new Republican President (Ulysses S. Grant) to solidify Republican control of both the Supreme Court and the lower courts.

To those ends, as part of the Judiciary Act of 1869 (which, among other things, restored the Court to its current size of nine justices), Congress authorized full pay in perpetuity for any federal judge (including Supreme Court justice) who resigned, was at least 70 years old, and had served at least 10 years in office. Within three years of the bill’s enactment, Grier and Nelson both took advantage of these pension benefits, clearing the way for two of Grant’s four appointments to the Court. Congress was thus able to use the pension power to nudge two justices off the bench—and thereby enable the incumbent President to reshape the Court.

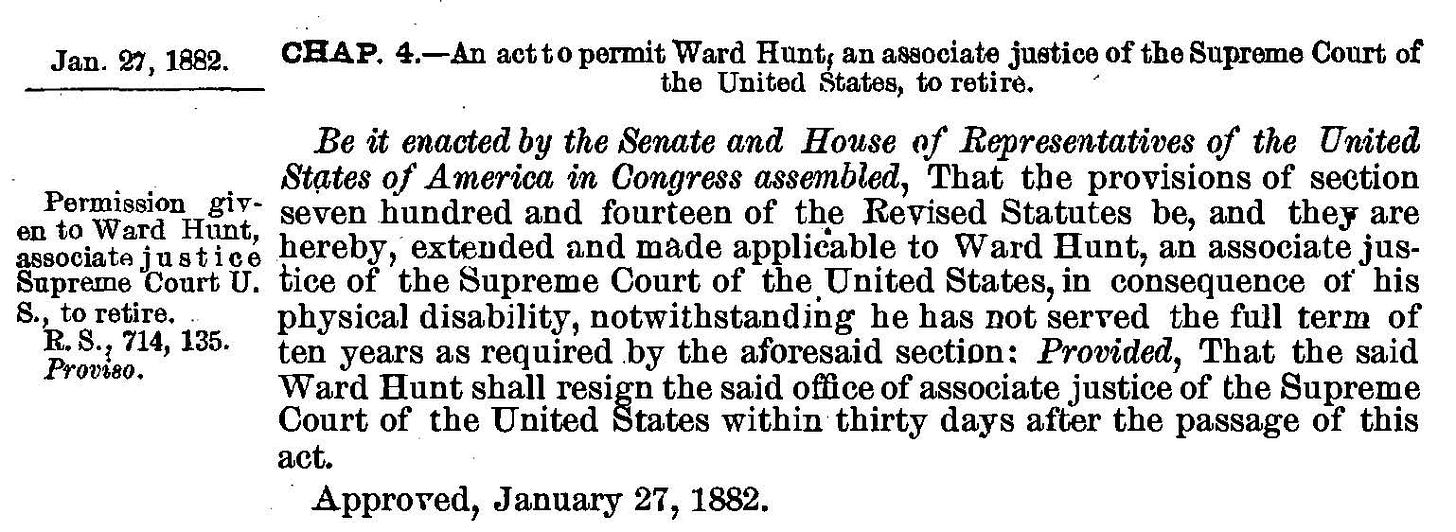

Nelson’s successor, Justice Ward Hunt, soon highlighted the most obvious gap in the 1869 act. After suffering a paralyzing stroke in 1878, Hunt refused to resign—because he was not yet eligible for the benefits Congress had provided (he was only 68, and had served only six years on the Court). After a long series of debates, Congress eventually passed a statute in January 1882 creating a pension just for Justice Hunt—so long as he retired within 30 days of that law entering into effect. Hunt quickly obliged.

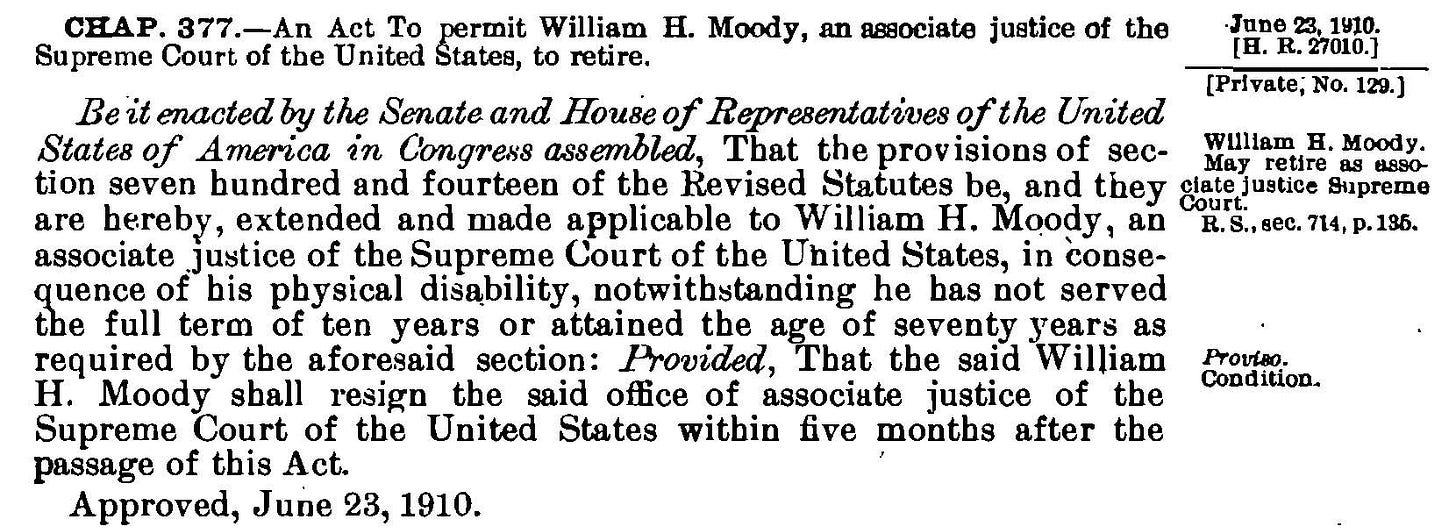

History would repeat itself in 1909, when Justice William Henry Moody, appointed to the Court by President (Theodore) Roosevelt in 1906, was forced to stop attending the Court’s sessions due to severe rheumatism. Moody refused to resign because, like Hunt, he was not yet eligible for the pension made available through the 1869 act. President William Howard Taft lobbied Congress for a similar accommodation for Moody—and, in 1910, Congress acquiesced:

Congress returned to the subject of judicial pensions and judicial retirement in 1919, but only with respect to lower federal court judges. For the first time, Congress provided for “retirement from active service” as an alternative to “resignation,” creating the status of “senior judges” on the federal district courts and courts of appeals for judges who continued to exercise at least some regular judicial duties and met certain age and service-duration requirements.

A judge who took “senior status” once they reached the relevant age and service thresholds would thus continue to hold (an) office—so that, in theory, their pensions could not be diminished thereafter. Such a proviso, it was hoped, would induce judges to stand aside before (or as soon as) they were no longer able to fully discharge the duties of their office, while allowing them to continue to perform those duties of which they were capable. (Today, for instance, senior circuit judges regularly sit alongside active judges on the courts of appeals, and senior district judges regularly hear cases as trial judges.)

On its face, the 1919 act did not apply to the Supreme Court. The consequences of that omission were made quite clear in 1932, in the midst of the Great Depression. A bill that reduced to a maximum of $10,000 all federal salaries lawfully subject to reduction had the (if not intended, then at least knowing) effect of cutting Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’s pension in half. Congress would subsequently restore Holmes’s pension in 1933, but only after significant pressure from the White House and Holmes’s (many) friends both on the Court and off of it.

The 1932 act also apparently provided a powerful incentive for two justices contemplating their own departures—Justices Willis Van Devanter and George Sutherland—to stick around. (Given that Van Devanter and Sutherland were reliable votes against most economic regulation, including central aspects of FDR’s agenda, it’s fascinating to wonder how differently history might’ve looked if the 1932 act hadn’t interrupted their plans.) Even though Holmes eventually had his full pension restored, the possibility that Congress could do the same thing to the pensions of other justices who resigned must not have been lost on the two conservatives. In the interim, the Supreme Court unanimously held in Booth v. United States that lower-court judges who “retired” under the 1919 act were protected by Article III against diminution of their “salaries” while retired. Booth thus constitutionalized the salaries of “retired” (as opposed to “resigned”) judges.

But it wouldn’t be until 1937, in the midst of the debate over FDR’s “Court-packing plan,” that Congress finally put the justices on par with lower-court judges. In a statute enacted on March 1, 1937, Congress granted the justices “the same rights and privileges with regard to retiring, instead of resigning, granted to judges other than Justices of the Supreme Court” by the 1919 act. Thus, for the first time, Congress created the position of “retired justice.” Given the Supreme Court’s intervening ruling in Booth, this measure clearly reflected Congress’s belief that justices who availed themselves of the retirement (instead of resignation) option would be protected from the same (temporary) fate that befell Justice Holmes. There is significant academic debate about whether the 1937 act was meant to defuse FDR’s Court-packing plan, or whether it’s better understood as an early salvo in the same war. But the upside was clear: Justice Van Devanter announced his retirement on June 2, 1937—almost certainly because he could now retire with full (and constitutionally protected) pay.

A host of subsequent amendments have tweaked the criteria for when justices can retire (and which duties they can exercise while retired). But the basic structure of Supreme Court retirement today remains unchanged: A retired justice can receive their full salary (and other forms of support, including an office and a law clerk) so long as they continue to “serve” under 28 U.S.C. § 371. One visible example today is Justice Souter, who sits from time to time on the First Circuit. (Retired justices have also often been part of reform proposals, including the possibility that they might be authorized to step in to sit on the Court in cases in which one of the active justices must recuse.)

The “senior judge”/“retired justice” model raises some interesting constitutional questions that Booth doesn’t fully (or, at least, persuasively) resolve. Even if retired justices hold an “office,” which office do they hold? If it’s their original office as a justice of the Supreme Court, how did that office become vacant such that it could be filled by their successor? And if the answer is that the office of “retired justice” is somehow distinct from the office of “justice in active service,” how does a justice who retires get “appointed” to the separate office of “retired justice” in a manner that is consistent with the Appointments Clause of Article II? There’s no nomination or confirmation to the office of retired justice—unless the argument is that the original nomination/confirmation to the Court included a simultaneous nomination/confirmation to the separate office of future retired justice. (That argument raises problems of its own, as Will Baude and Eighth Circuit Judge David Stras, among others, have identified.) Even if retired justices are “inferior” officers, Congress still must provide for their appointment by “the President alone,” “the Courts of Law,” or “the Heads of Departments.” So when Justice Breyer retired, which of those entities “appointed” him to the position of retired justice?

The arguments in the other direction are also messy. If a justice abandons their office at the time of their retirement, by what right do they exercise judicial duties on lower courts as a retired justice? Indeed, the model of retired justices (and senior judges) presupposes that those jurists are continuing to hold office as Article III judges (hence the result in Booth). There’s something that seems normatively persuasive about that view (since Congress gets to create offices in the first place). It’s just not obvious which office they hold (or how to get around the Appointments Clause issues that arise from any world in which the second office is different from the first).

However those Appointments Clause issues are resolved, and even if one assumes that retired justices are constitutionally protected against salary diminution under Booth, that’s true only for justices who retire under the terms of the 1937 act. As the history recounted above underscores, Congress has the unquestionable power to change those terms—even if those changes could only apply to justices who retire going forward. What that point underscores is that, although Congress has, for the moment, surrendered its ability to use its control of the justices’ pensions as a cudgel, that arrangement is a transitory policy choice, not a permanent and indispensable feature of the constitutional separation of powers. If Congress wanted to once again use its power over the justices’ pensions as a lever, nothing in the Constitution would get in its way.

SCOTUS Trivia: No Retired Justices

As the above discussion hopefully made clear, the first-ever “retired” justice was Willis Van Devanter, in 1937. And today, there are four retired justices (O’Connor, Souter, Kennedy, and Breyer). But when was the last time that there were no retired justices?

The answer is from April 15, 2002 through January 31, 2006. Justice Byron White was the only retired justice at the time of his April 2002 death; and the next justice to retire was Justice Sandra Day O’Connor on January 31, 2006. There’s been at least one retired justice every day since.

Having no retired justices has actually been relatively rare since the practice began in 1937; before White’s death, the last time that there had been no retired justices was the brief period between Justice Potter Stewart’s death in 1985 and Chief Justice Burger’s retirement in 1986. (Justice Goldberg was still alive during that period, but he had resigned from the Court, since he was ineligible for retirement.) And the last justice to resign from the Court, rather than retire, wasn’t Goldberg; it was Justice Abe Fortas in 1969.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! Because of Thanksgiving, this week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Wednesday. And we’ll be back with a regular issue next Monday—looking back at the first woman to be admitted to practice (and argue) before the Supreme Court: Belva Lockwood.

Happy Monday, everyone. I hope that you have a great week!

Is Souter still hearing lower court cases? He regularly did so but have not heard of any in a while.

Did Kennedy or Breyer hear any lower court cases after leaving the Court? Again, I am not aware of any. I recall Breyer joining academia in some fashion.

One law professor thought Stevens never "really" retired & felt it unethical he proposed amendments and so forth.

Regarding the power of Congress to use pensions to motivate judicial retirement/etc I think that ship has sailed. They are certainly paid well but I suspect that any justice willing to trade the power and prestige of the court for cash could easily rake in far more just in speaking fees nowadays if they so choose not to mention what they could get if they became even a pro forma partner at some law firm.

Currently the justices tend to avoid this, in part because they are all fucking loaded, and also because they want the respect of seeming to have a sense of decorum etc.. which suggests that any pension bribery wouldn't work and that any big stick (retire or no pension, even if constitutional) could backfire.