5. The Impeachment of Justice Samuel Chase

The only impeachment of a Supreme Court Justice started amid a partisan fight over the Court, and ended as a powerful precedent for judicial independence

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us. Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying what you’re reading, I hope you’ll consider sharing it with your friends (or even with Yankees fans):

On the Docket

In addition to holding oral arguments in two major cases (one about whether a Colorado wedding website designer has a First Amendment right to refuse to design a site for a same-sex couple and one about the so-called “independent state legislature” theory), the Court granted certiorari in four cases last week, bringing the total number of cases on the merits docket this Term to 46.

This week ought to be a quiet one. After releasing the last routine Order List for 2022 at 9:30 ET (likely to mostly comprise denials of certorari), the Justices are set to take the bench this morning, but only for bar admissions (“non-argument days” are usually for bar admissions and opinion announcements, but none of the latter are expected). They’re not otherwise set to meet in person again until the next Conference on Friday, January 6, 2023.

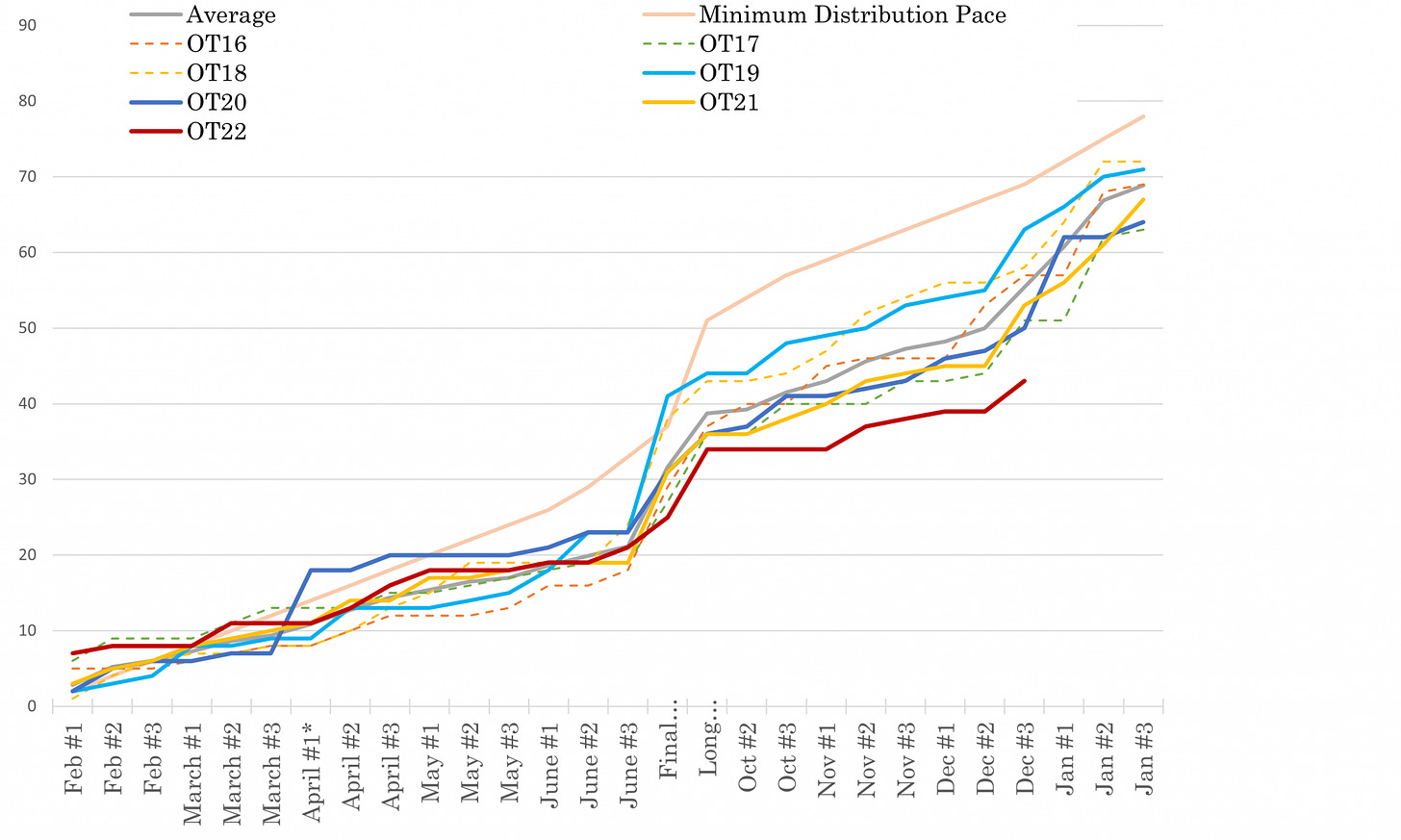

Although this December break is typical for the Court’s current schedule, it comes with the Court further behind in its work, at least publicly, than in any recent Term. In a post at his “Empirical SCOTUS” blog last Monday, Adam Feldman noted that “[t]his is the first time since the Court began its term on the first Monday in October in 1917 that the Court has not released a slip decision through the beginning of December.” Unless there’s a surprise in today’s Order List, it looks like we’re going to make it to at least Monday, January 9 (the next time the Justices are scheduled to take the bench) without any opinions for the Court. That’s … unusual.

In a future issue, we’ll spend some more time looking at the pace of the Court’s work, and consider potential explanations for why the Court is, at least publicly, doing so much less (and more slowly) than as recently as a decade ago. The relevant point for now is that such a quiet December likely presages a busy spring.

The One First Long Read: Impeaching a Justice

With an honorable mention to the late 1860s, there’s no period in American history in which the political branches behaved as aggressively toward the Supreme Court as 1801–05. Some of it was retaliatory: After being trounced at the hustings in the Election of 1800, the lame-duck Federalists,1 while going through 36 ballots to break the presidential election tie between Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr (both Democratic-Republicans in a time before the Twelfth Amendment), also took the time to enact the Judiciary Act of 1801.

That Act, which Democratic-Republicans derided as the “Midnight Judges Act,” sought to entrench Federalist control of the federal judiciary even as the Federalists had lost control of the political branches. It abolished the deeply unpopular practice of “circuit riding” by SCOTUS Justices, replacing the Justices’ circuit-riding duties with 16 standalone “circuit judges”; it reduced the size of the Court from six seats to five (to deny Jefferson/Burr the chance to immediately put a Democratic-Republican on the bench upon the next vacancy); and it created a handful of other judicial positions to be filled by Federalists (like the D.C. Justice of the Peace job to which William Marbury was nominated and confirmed).

As the story goes, President Adams stayed up the night before Jefferson’s inauguration signing judicial commissions (hence the “Midnight Judges”), leaving it to his outgoing Secretary of State (and dual-hatted Chief Justice) John Marshall to seal and deliver them. Marshall’s role led to one of the greatest uses of third person in a Supreme Court opinion, when Chief Justice Marshall had to refer to Secretary of State Marshall in Marbury:

Upon taking power in March 1801, the Democratic-Republicans set to pushing back against the Federalist judiciary. First, they repealed the Judiciary Act of 1801, effectively abolishing the new circuit judgeships and re-committing the Federalist Justices to spending much of their time riding circuit (a practice Congress wouldn’t ultimately eliminate until 1891).

Three months later, in the Judiciary Act of 1802, Congress (1) restored the Court’s sixth seat; (2) restructured the lower courts; (3) created a new August Term in which a single Justice would preside over procedural matters (what Ross Davies has called the “Rump Court”); and (4) “moved” the beginning of the full Court’s annual Term from December to February. Because the Act was enacted in April, this last measure had the (rather deliberate) effect of preventing the Court from sitting at all in 1802. It was a not-very-subtle threat to the Court that was already considering a major case challenging the constitutionality of the 1802 Repeal Act—Stuart v. Laird.

The rest is history, at least to first-year law students. The Court avoided a constitutional confrontation in Stuart by effectively deciding a different question than the one that was presented (leaving the Democratic-Republicans’ abolition of the circuit judgeships in effect, and re-instituting circuit riding). And in the lower-profile companion case, Marbury v. Madison, Marshall famously cemented the Court’s power to strike down federal statutes in a case in which he applied that power to prevent the Supreme Court from ruling against the Jefferson administration (by holding that section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789 unconstitutionally authorized the Supreme Court to issue a writ of mandamus directly to the Secretary of State). Thus, the jurisprudential storm passed; the Democratic-Republicans won the battle, even if Marshall (and the Court) eventually won the war.

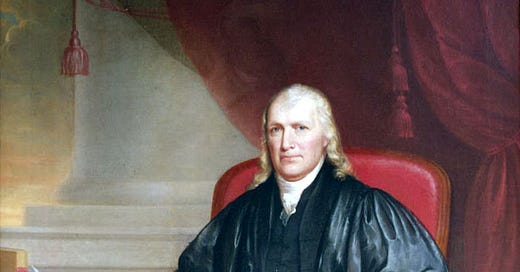

But the Democratic-Republicans had one more card to play, and they played it in early 1804. By a 73-32 vote, the House of Representatives voted to impeach Associate Justice Samuel Chase—still the only instance in American history of a Supreme Court impeachment. The real story, though, is what happened next.

Any unofficial list of best Supreme Court Justice nicknames would have to start with Chase. A notoriously gruff and intimidating presence, his reddish-brown complexion led contemporaries to dub him “Old Bacon Face.” As Chief Justice Rehnquist put it in a 2003 speech, “Chase was one of those people who are intelligent and learned, but seriously lacking in judicial temperament.”

Chase had been a towering (if not overbearing) figure in Maryland politics and legal circles since early adulthood. He served in the General Assembly; was elected to the Continental Congress; and was one of Maryland’s signers of the Declaration of Independence. Although Chase became something of an Anti-Federalist at the time of the ratification of the Constitution (primarily because it lacked a Bill of Rights), his politics veered toward the Federalists as he served as a Maryland state court judge, first as Chief Justice of the Baltimore criminal court, and then as Chief Judge of the Maryland General Court. It was from that position that President Washington nominated him to the Supreme Court in 1796—to fill a vacancy created by the resignation of Justice John Blair from Virginia.

Chase’s work on the Court is largely overshadowed by his work riding circuit, especially a series of controversial charges to grand juries in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Richmond. (One of the most important responsibilities of Justices while riding circuit was to charge federal grand juries considering whether to vote indictments in criminal cases.) Chase was a staunch defender of both the controversial Sedition Act of 1798 and the Adams administration’s use of that statute to prosecute Democratic-Republicans, and was … overzealous … in instructing grand juries in several prosecutions brought by the federal government against vocal critics of the Adams administration and one alleged traitor. Chase also actively campaigned for Adams during the run-up to the Election of 1800, at one point depriving the Supreme Court of a quorum through his absence.

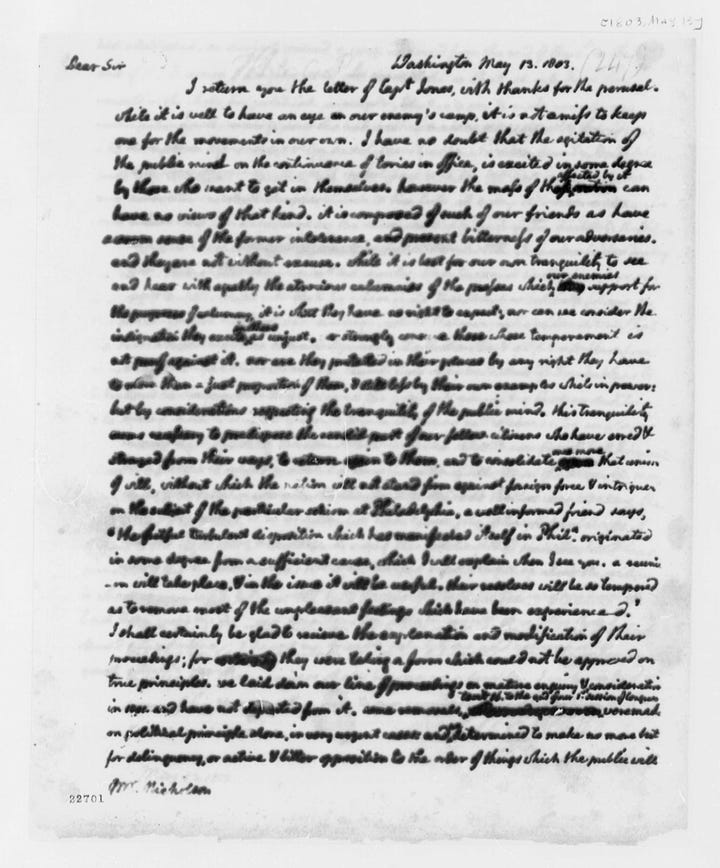

The final straw came in 1803, when Chase publicly denounced the Judiciary Act of 1802, and the Democratic-Republicans more generally, in a charge to a Baltimore grand jury. In response, President Jefferson sent a carefully worded letter to Maryland congressman (and devout Anti-Federalist) Joseph Nicholson, subtly suggesting that the House might wish to look into Chase’s “good behavior” as reflected in his conduct on and off the bench and his grand jury charges.

Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution provides that “The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour.” The implicit understanding was that, although impeachment and removal of judges would be one of the legislature’s most significant checks on the judiciary, judges should be insulated from such political checks so long as they engaged in “good Behaviour.”

Chase’s impeachment thus became an early referendum on what constituted “good Behaviour.” The Democratic-Republicans in the House believed that Chase had run afoul of that protection by acting in such a transparently partisan and non-judicial manner in publicly defending the Sedition Act; attacking Democratic-Republicans; and facilitating the prosecutions of James Callender, John Fries, and others through his grand jury charges. They ultimately voted eight articles of impeachment, although the articles largely applied to Chase’s handling of four specific cases. (All the while, there were suggestions in some quarters that, if Chase was removed, the House might set its sights next on Chief Justice Marshall.)

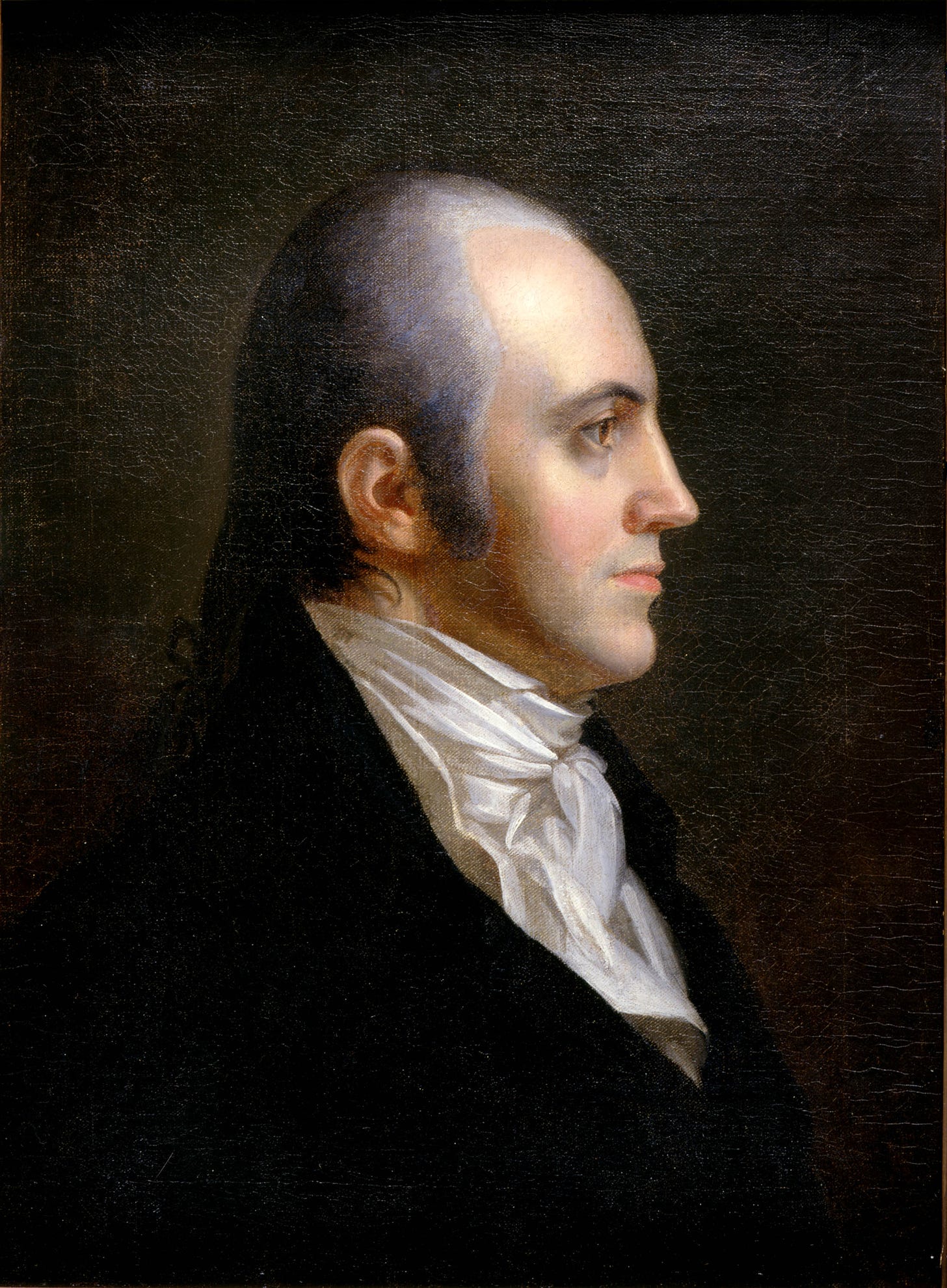

The Senate convened to conduct Chase’s trial in February 1805. The timing was more than a little … awkward. Jefferson had been convincingly re-elected in the Election of 1804, but he had unceremoniously abandoned his first Vice President, Burr, who was now facing murder charges in New Jersey for the July duel in which he had killed Alexander Hamilton. This was the lame-duck Senate, though, so Burr was still the presiding officer. That reality led to the strange scenario, as one contemporary observer put it, where, although the murderer is usually arraigned before the judge, here, the judge was arraigned before the murderer.

Burr’s complicated presence aside, the Senate trial produced a remarkable divide among the Democratic-Republicans (who held a 25-9 majority in the upper chamber). Although the Federalists sided with Chase, the Democratic-Republicans split, with a number of them publicly expressing the belief that, although they found Chase’s conduct disagreeable if not distasteful, they did not believe that low-quality (or even partisan-motivated) judging was a basis for removal from office. Partisan differences, and even poor-quality judging, did not fall below the Constitution’s “good Behaviour” floor.

Thus, although a majority of the Senate voted to convict Chase on three of the eight articles, the closest the Senate came to the constitutionally required two-thirds majority to remove him was on the charge relating to Chase’s behavior before the Baltimore grand jury in 1803. That charge mustered a 19-15 vote—four votes short. Faced with an opportunity to create a vacancy on the Court that President Jefferson could fill, six Democratic-Republicans opted to promote judicial independence, instead.

There’s a lot more to say about the rich and remarkably substantive impeachment proceedings themselves (which are summarized in Chief Justice Rehnquist’s 1992 book, Grand Inquests). The key for present purposes is that the Chase acquittal set an important practical precedent for judicial independence—cementing in congressional practice the understanding that there’s lots of poor and/or partisan judicial conduct that, for better or for worse, doesn’t fall below Article III’s “good Behaviour” minimum.

Thus, although 14 lower-court judges have been impeached (and eight have been convicted and removed, in addition to three more who resigned before they could be convicted), almost all of those cases have involved affirmatively criminal conduct by the impeached judge—where the issue was not the substantive quality of their judging, but the objective unlawfulness of their behavior.

In 1969, Justice Abe Fortas resigned under threat of impeachment, where the charges related to behavior alleged to be unethical, not (necessarily) unlawful. But whether or not it ought to be so, the historical bar for impeaching a Justice remains quite high today—thanks largely to the 1805 Senate’s refusal to convict “Old Bacon Face.”

SCOTUS Trivia: Family Names in Common

The focus on Justice Chase gives me an excuse to share one of my most useless pieces of Supreme Court trivia: The nine family names shared by multiple Justices (including, as of this year, the first to be shared by three Justices).

Chase himself was followed by Chief Justice Salmon Chase (1864–73), who, among other things, presided over the first presidential impeachment trial in U.S. history in 1868.

John Marshall Harlan (1877–1911) and his grandson, John Marshall Harlan II (1955–71), are the source of my favorite-ever question from a first-year law student: “How did Justice Harlan stay on the Court for so long??”

There have now been three Justices Jackson. Howell Edmunds Jackson (1893–95); Robert H. Jackson (1941–54); and Ketanji Brown Jackson (2022–).

One of the more obscure examples, because they both served in the Court’s early years, are the Justices Johnson: Thomas Johnson (1791–93), and Jefferson’s first (and most influential) appointee, William Johnson (1804–34).

Then there are the Justices Lamar. Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus (L.Q.C.) Lamar (1888–93); and Joseph Rucker Lamar (1911–16).

One example that most SCOTUS nerds get are the Justices Marshall: Chief Justice John Marshall (1801–35); and Justice Thurgood Marshall (1967–91), whose appointment figured prominently in last week’s trivia.

Another example likely to be more familiar to folks are the Justices Roberts: Justice Owen Roberts (1930–45); and Chief Justice John Roberts (2005–). It was Owen Roberts whose “switch in time” was so central to the constitutional drama of 1937, about which more in a future issue.

Back in the more obscure column are the Justices Rutledge. John Rutledge served as both Associate Justice (1790–91) and Chief Justice (1795). There will be more to say about him in a future issue; I’ll just note for now that Rutledge (1) never showed up for a day of Court during his first stint; and (2) is the only one of 12 recess-appointed Justices ever to be rejected by the Senate, which is how his second stint ended. And Justice Wiley Rutledge (1943–49) is my vote for one of the more under-rated Justices in the Court’s history.

Last, but not least, are the Justices White. Edward Douglass White served as Associate Justice (1894–1910) and Chief Justice (1910–21), the first sitting Associate Justice to be elevated to the center chair (at least in part because then-President Taft correctly thought that appointing the 65-year-old White would leave open the possibility that Taft could succeed him). And Justice Bryon White (1962–93) is the only Justice, among lots of other things, to play in the NFL.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. If you liked it, I hope you’ll consider sharing it:

And if you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content, please consider becoming one. This week’s bonus issue, which will be available only to paid subscribers, will include my reflections on (and advice for) what it’s like to argue before the Court—the good, the bad, and the ugly (i.e., arguing over telephone):

Happy Monday, everyone! Have a great week!

Until the Twentieth Amendment was ratified in 1933, the lame-duck Congress remained in session until March 3.

That's not the passive voice that Marshall was using. Its the 3rd person . Passive would be: 'the letters were carried by him ' rather than 'he carried the letter' which is active. And now that I’ve been a pedantic prick I’ll finish reading the rest of the article. Which is great. I learn loads from you.

Thank you for the useful list of common names. If you include female justices' maiden name, two entries may be added:

1. Sandra Day O’Connor (1981–2006), the first female and last formerly-elected-official Justice, and William R. Day (1903–22);

2. again—Ketanji Brown Jackson (2022–) and Henry Billings Brown (1891–1906), ironically the author of Plessy v. Ferguson and an opponent of women suffrage. Interestingly, then-Judge Howell Jackson advised President Harrison to appoint Brown to the Supreme Court in 1889 (Harrison heeded the advice a year later). Brown advised Harrison to appoint Jackson in 1893 (Harrison did). So, the Brown-Jackson connection is a quite old.