47. The First Monday in October

Although the reason why the Supreme Court's annual session begins today, specifically, has become more than a little anachronistic, Congress's role in *setting* that date still matters quite a bit

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it with your networks (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

Happy 28 U.S.C. § 2 Day! (“The Supreme Court shall hold at the seat of government a term of court commencing on the first Monday in October of each year . . . .”). As you likely knew even before reading this, the Supreme Court officially opens its October 2023 Term this morning, with a long Order List expected at 9:30 ET (most of which will be denials of certiorari from last week’s “Long Conference”), followed by the first argument of the Term at 10:00 ET (in a technical dispute over federal criminal sentencing). In all, the justices are hearing only three arguments this week, but tomorrow is the potentially blockbuster CFPB case (more on that in a future issue), followed by a dispute over “tester” standing under the Americans With Disabilities Act on Wednesday.

As last week’s issue predicted, the justices on Friday added a number of new cases (12!) to their docket for the new Term. I’m not going to summarize all 12 here (Amy Howe has a typically helpful post on the subject over at SCOTUSblog). But it seems to me that the two biggest grants are in the NetChoice cases—challenges to very similar laws enacted by Florida and Texas that impose unprecedented constraints on the extent to which social media companies are allowed to moderate the content of their users. The Fifth and Eleventh Circuits divided on the constitutionality of these laws; the Eleventh Circuit agreed with the district court that Florida’s law violates the First Amendment; the Fifth Circuit held, contra the district court, that Texas’s law is constitutional. (Folks might remember that, after the Fifth Circuit stayed the district court’s injunction, the Supreme Court vacated that stay, putting Texas’s law back on hold, by a 5-4 vote.) The circuit split made it virtually inevitable that the justices would step in, but these are massively important cases not just for the future of free speech on the internet, but for the ability of states to tell private businesses what they can and can’t do when it comes to interacting with their clients. Indeed, as I suggested back in February, these cases, and not last term’s section 230 cases (on which the justices largely punted), are the real referenda on big tech and the First Amendment.

Speaking of social media, perhaps the most interesting development at the Court last week was the justices’ lack of action on the Biden administration’s emergency application asking the justices to stay a Louisiana district court injunction that purports to prohibit a wide range of contacts between government officials and social media companies. Justice Alito had initially extended his administrative stay of that injunction through the end of the day last Wednesday (September 27), but midnight came and went with no action from the Court (and there has still been none). The likely explanation for the Court’s silence is subsequent developments in the Fifth Circuit. After what that court described as a “clerical error,” the court of appeals extended its stay of the district court’s injunction while it considers Louisiana’s pending petition for rehearing (which is asking the Fifth Circuit to leave more of the district court’s injunction intact). As the Biden administration wrote to the Court Wednesday morning, the Fifth Circuit’s … strange … behavior doesn’t obviate the need for emergency relief, but it at least obviated the need for relief by Wednesday. Presumably, once the Fifth Circuit rules on Louisiana’s petition, the Biden administration will renew its application with the justices. Given that nothing the Fifth Circuit does is likely to undermine the Biden administration’s case for emergency relief, it’s more than a little weird that the Court couldn’t be bothered to say anything publicly—and seems to be holding the application in abeyance.

And speaking of emergency relief, the justices on Tuesday also turned away, over no public dissents, Alabama’s requests to allow it to use a congressional district map that did not have a second “majority-minority” district, notwithstanding the 5-4 ruling in June that such a district, or something very close to it, was required by section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Because of Tuesday’s denials of emergency relief, Alabama now must use a court-ordered map for the 2024 election cycle, which likely means a second House district in Alabama in which the Democratic candidate will be favored.

Suffice it to say, it was a busy way to close out the October 2022 Term…

The One First “Long Read”: The History of the First Monday

“First Monday”—a reference to the annual beginning of the Supreme Court’s Term—has become a staple of the Supreme Court’s lexicon. One of the two short-lived 2002 network TV dramas devoted to the Court was titled “First Monday” (yes, there were two!); a podcast about the Court was called “First Mondays”; you get the idea.

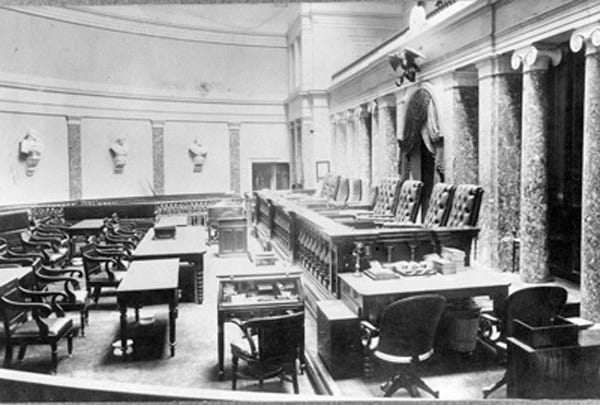

Indeed, that the Supreme Court’s annual term begins on the “first Monday in October” has been fixed by statute since September 6, 1916—and has been the rule since the beginning of the Supreme Court’s October 1917 Term (the 1916 statute didn’t take effect until after the Court’s 1916 Term began). Here’s the present-day version of 28 U.S.C. § 2:

But as technical a point as it might seem, the history of when the Court’s term “began” prior to 1917 is actually of some import—not just to provide a nerdy understanding of the cycles of the Court’s decisionmaking, but also to see how Congress at least used to exercise more control over the justices’ work.

In section 1 of the Judiciary Act of 1789, Congress provided that the Supreme Court would hold two “sessions” per year: “the one commencing the first Monday of February, and the other the first Monday of August.” (Yes, the “first Monday” formulation, if not the “in October” part, dates all the way to the Founding.) Both sessions were meant to be relatively brief, allowing the justices to perform what was then their primary function—“riding circuit” as judges on the intermediate federal courts.

That twice-a-year pattern held through the pitched battles between the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans after (and over) the Election of 1800. As part of the Judiciary Act of 1801 (which the lame-duck Federalists enacted in February 1801—while they were deadlocked over breaking the electoral college tie between Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr), Congress moved the Court’s two sessions to June and December (which, among other things, were far nicer months for the Federalist justices to have to spend in Washington than February and August).

But as part of the Judiciary Act of 1802 (most of which was an effort to kneecap the Federalist-controlled courts), Congress changed this structure in two key respects. It went back to the February/August session schedule; and it converted the August sitting into a “rump Court” held by a single justice. Thus, the full Court would only have a single annual session going forward. And because the 1802 act was enacted in April (before the previously scheduled June session but after the new February session), the full Court wouldn’t (and didn’t) sit at all at any point that entire year. That was … not an accident.

Indeed, the relevant point in this otherwise technical history is how Congress used its control over the Court’s meeting schedule as leverage, either to help or hurt the justices. That point was not lost on the Court, which kept to that schedule (apparently with little public complaint) until 1827. Then, at the Court’s request, Congress started moving the beginning of the Term earlier—so that the justices would be able to dispense with more of their business in the winter months (when Congress was also typically in session). Thus, 1827 saw the beginning of the term move to the first Monday in January; it moved to the first Monday in December in 1844 (which spelled the end of any hope of having SCOTUS Terms and calendar years be co-extensive); and, as the Court’s docket exploded after the Civil War, it moved to the second Monday in October in 1873. (Congress had ended the “rump Court” practice as of 1838.)

Docket management was also the justification for the final tweak to the calendar—in the 1916 amendments to the judicial code. Because Congress had given the Court new categories of appellate jurisdiction both in 1914 and in the same 1916 bill, the Court sought and received an extra week within which to complete its work. Thus, the first “first Monday in October” in the Court’s history was Monday, October 1, 1917. (There’s a Red October joke in here somewhere.)

Although the beginning of the term has thus been fixed for 106 years, the end has not been. As I’ve noted before, until 1980, the justices would formally “adjourn” when they rose for their summer recess, which meant that the Court would have to convene for a “Special Term” over the summer if a case arose that required the full Court’s resolution before the next term began. (This is also why the Supreme Court’s docket numbers reset at the beginning of the summer recess, rather than the beginning of the new Term, which, among other things, causes … statistical mischief.)

The justices quietly switched to a “continuous” term starting in 1980, and memorialized that shift (in Rule 3) only in 1990. Thus, Rule 3 today provides that: “The Court holds a continuous annual Term commencing on the first Monday in October and ending on the day before the first Monday in October of the following year.”

The move to a continuous term 23 years ago means it doesn’t much matter any more when the justices “begin” their work for a specific year; the Court is always legally able to act, and having the start date be in one month versus another seems somewhat less important if the gap between terms is infinitesimal. Instead, the only real reason to keep the rule is tradition—the Court is used to running on this calendar; to clearing its decks before the summer recess; to having clerks turn over during the summer; etc. But the procedural reason for moving the date around—the growing size of the docket—is … no longer a concern. As for Congress using the beginning of the Court’s term as a means of exerting leverage over the Court in other respects, well, that’s no longer a concern either, even if some might think it should be.

SCOTUS Trivia: The Rarest Argument Month

Because of the calendar shifts documented above, along with the handful of “Special Terms” that the Court ended up holding in various pre-1980 summers, the full Court has heard oral arguments in at least some cases in every calendar month of the year. (Today, the Court regularly holds arguments each month between October and April.) Arguments in May, June, July, August, and September have become quite rare under the current calendar. But it turns out that the true rarity is an August argument.

The last time the full Court heard oral argument in May was in 2021 (the late-arising argument in Terry about the First Step Act). The last June argument was in 1998 (in an attorney-client privilege dispute arising out of the independent counsel investigation). The last July argument was in 1974 (United States v. Nixon). And the last September argument was in 2009 (the re-argument in Citizens United). But for the last August argument, we have to go all the way back to 1958, and the Special Term the Court convened to decide Cooper v. Aaron. Although the Court’s formal opinion in the case notes that the matter was argued on September 11, 1958, the Court also heard argument in the emergency application that led to Cooper, titled Aaron v. Cooper, on August 28.

Given the Court’s current calendar, it’s not exactly a surprise that August is the rarest argument month. But it’s a sign of how much the Court’s practices have evolved since the Founding; August arguments were the norm for the Court’s first 11 years—including what appears to have been the first-ever argument before the full Court, in West v. Barnes, on Tuesday (nuts!), August 2, 1791.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone next Monday.

Happy (First!) Monday, everyone. I hope that you have a great week.

Steve,

I want to thank you for your outstanding research and history of the US Supreme Court. Thank you for sharing your truth with your readers in such an open and inviting style. Happy Monday.

Delightedly wonky.