45. Justice Kavanaugh and the Return of the Alabama Redistricting Cases

Justice Kavanaugh is once again at the center of the dispute over Alabama's congressional redistricting. The harder question is whether it's his fault or the state's.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it with your networks (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

Although the week before the Long Conference is usually a quiet one at One First Street, the justices have at least two major emergency applications that they’re likely to address this week or early next. The first, about which I’ll have much more to say below, is Alabama’s request that the Court once again freeze two district court decisions blocking the state’s effort to redraw its seven congressional districts to include only a single majority-minority seat (in a state the population of which is 27% Black).

The second is an emergency application from the Biden administration (its 12th, if you’re scoring at home)1 to freeze in its entirety a rather remarkable and unprecedented district court injunction, which blocked contacts between a wide range of federal government officials and social media companies—on the putative ground that those officials were unconstitutionally “jawboning” social media networks in their attempts to prevent the spread of misinformation. The Fifth Circuit stayed most of Judge Doughty’s ruling, but left enough of it intact to warrant yet another request from the Justice Department for emergency relief in a case from the New Orleans-based federal court of appeals. (I’ve written before about how bad the Fifth Circuit’s track record on these kinds of cases has been this term.)

Last Thursday, Justice Alito, in his capacity as Circuit Justice for the Fifth Circuit, issued an “administrative” stay of the injunction, but (as is his m.o.) provided that the stay will expire at 11:59 p.m. (ET) this Friday night. It’s worth noting that Alito has already had to extend his arbitrary deadline on administrative stays twice this term, but short of that, it’s a good bet that we get decisions in both cases by the end of the week—yet another reminder that those who would preview the Court’s upcoming term by telling you principally about the cases being argued will … miss a lot. (More on that next Monday.)

The One First Long Read: Alabama Redistricting, Redux

If you’ve seen headlines about how the Supreme Court is about to consider Alabama’s post-2020-Census redistricting and thought that the Court … just did that, you’re not wrong. As for how these cases are back at the Court, and how Justice Kavanaugh is right in the middle of it, read on:

After the 2020 Census, Alabama (like just about all of the other 43 states that have more than one House district) set about re-drawing the map dividing its seven districts—pretty transparently to maximize partisan advantage. In a state that voted 62-37 for President Trump (which translates to roughly a 5-3 split in the House), the (gerrymandered) legislature adopted, and Governor Ivey signed, a map that created six safe Republican seats and one safe Democratic seat—a “majority-minority district” in a part of the state known as the “Black Belt.” Immediately after the map was signed into law, it was subject to two different challenges, which argued that the map violates both section 2 of the Voting Rights Act and the Constitution. Because of quirks in how redistricting claims are assigned to lower federal courts, one of the suits was assigned to a “three-judge” district court (with two district judges and one Eleventh Circuit judge); the other was assigned to a more conventional (single-judge) district court.

In January 2022, both district courts found that the map was likely unlawful, and thus entered preliminary injunctions that would have barred Alabama from using them in the 2022 midterm cycle. But in an unsigned, unexplained order on February 7, the Supreme Court, by a 5-4 vote (with Chief Justice Roberts joining the three Democratic appointees in dissent) “stayed” both rulings—allowing the map to go into effect. In a separate concurrence by Justice Kavanaugh, joined by Justice Alito, Kavanaugh suggested that he was voting for the stay not because he was convinced Alabama was going to prevail, but because it was too close to the 2022 midterms, so the so-called “Purcell principle” provided that federal courts should stay their hand. (This invocation of Purcell has been roundly and widely criticized.) The upshot was that Alabama got to use its (unlawful) map in the 2022 midterm cycle, which produced at least one extra Republican seat in the House. Coupled with a similar ruling in a case from Louisiana, and lower-court rulings in Ohio and South Carolina relying on the Supreme Court’s interventions in Alabama and Louisiana, you can draw a pretty straight line from the Court’s interventions in the 2022 redistricting cycle and the current Republican margin of control in the House. (For more on all of this, see my earlier post on the subject after the Court’s June ruling.)

And yet, when the Court decided the merits of Alabama’s appeal in June 2023, it sided with the district courts and blocked the map. Chief Justice Roberts, writing for the three Democratic appointees and Justice Kavanaugh, held that, under the Supreme Court’s controlling precedent (its 1986 ruling in Thornburg v. Gingles), Alabama’s map violates section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. (The majority also rejected Alabama’s invitation to overrule Gingles.)

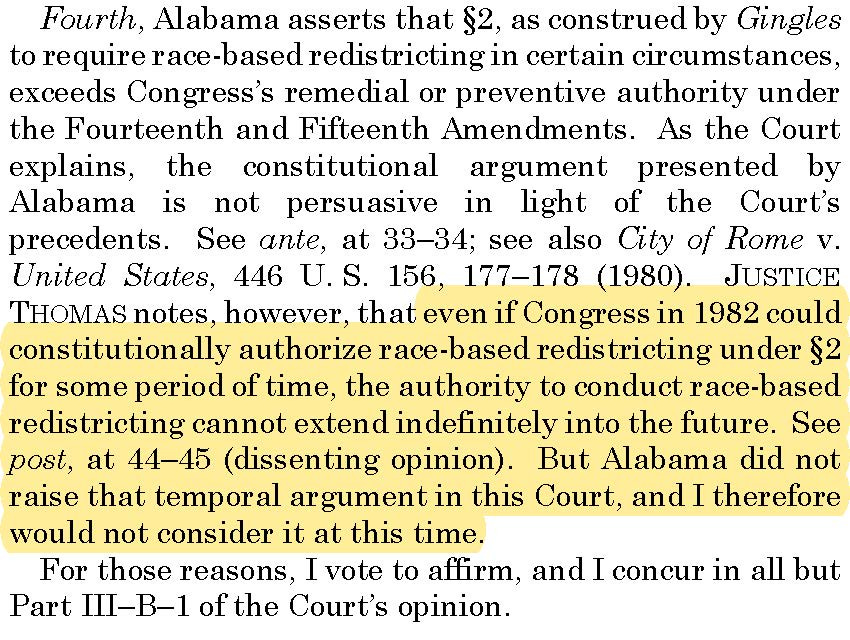

If matters had ended there, it would be hard to understand Alabama’s behavior over the last three months. But Justice Kavanaugh (the only justice in the majority who had also voted to stay the district court rulings) appended a short concurrence, in which he stressed that Alabama had not made an argument he found at least superficially attractive. As he summarized the argument (defended in Justice Thomas’s dissent), “even if Congress in 1982 could constitutionally authorize race-based redistricting under §2 for some period of time, the authority to conduct race-based redistricting cannot extend indefinitely into the future.” In other words, the idea is that Congress’s authority to require majority-minority districts consistent with Gingles … can expire. As Kavanaugh concluded, though, “Alabama did not raise that temporal argument in this Court, and I therefore would not consider it at this time.” Here’s the passage in full:

Usually, if a party fails to raise an argument below, they forfeit that argument not just for the duration of the proceedings in that court, but for the rest of the case. Were it otherwise, parties would be free to raise issues on appeal (or on remand) that lower courts had not previously had an opportunity to consider. But armed with Thomas’s dissent and Kavanaugh’s concurrence, Alabama … refused to draw a second majority-minority district on remand, and then defended its refusal at least in part by reference to this argument. (It also claims that the Supreme Court’s decision does not require a second majority-minority district so long as “other” redistricting factors are satisfied.) The district courts rejected those arguments (with some fairly harsh language for Alabama about its behavior), but that contention is now part of the basis for Alabama’s appeals of the district court’s rulings—and its requests for stays of those rulings pending appeal. Indeed, Alabama is invoking the Kavanaugh/Thomas constitutional argument in urging the Court to interpret section 2 of the Voting Rights Act to avoid that constitutional question.

In other words, Justice Kavanaugh’s concurrence has now put him right in the middle of this mess. Given what both Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Kavanaugh wrote in June, Alabama’s statutory defenses of its new map are … very weak—which is why so many folks have accused Alabama of “defiance” of the Supreme Court’s mandate. But the constitutional avoidance argument only has even a semblance of teeth because Justice Kavanaugh said it might. Consider this story from Saturday in the Alabama Political Reporter—asserting that “Alabama lawmakers working in conjunction with state Attorney General Steve Marshall’s office and Washington D.C. lawyers had ‘intelligence’ that Supreme Court Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh . . . is open to rehearing the case as a constitutional challenge to the validity of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.” Although the APR story suggests that the “intelligence” arises from a series of personal contacts between lawyers working on the case and Kavanaugh, it seems to me that the “intelligence” is there for all to see—in Kavanaugh’s concurrence.

The upshot is that Alabama’s return to the Court puts Justice Kavanaugh into a sticky wicket at least largely of his own creation. On one hand, Alabama is now raising the constitutional argument that Kavanaugh did not dismiss out of hand in June. On the other, they’re raising it only because of what Kavanaugh said (having failed to raise it below); and it’s not remotely clear how, even if that argument might be plausible, it would justify emergency relief now—when the equities on the other side include Alabama conducting a second congressional election using a map that violates the Voting Rights Act. Indeed, basing emergency stays on a novel (and not fully briefed or argued) interpretation of the unconstitutionality of section 2 of the Voting Rights Act seems, in some respects, even more indefensible than the invocation of Purcell that Kavanaugh used to defend last February’s stays. And if Kavanaugh joins with the four June dissenters to allow Alabama to use the map it submitted on remand, it will surely leave a rather sour taste in the mouths of those who think the Court had settled the matter three months ago.

Justice Thomas has ordered the plaintiffs to respond to Alabama’s application by 5:00 p.m. (ET) on Tuesday. Alabama has asked the Court to rule no later than October 1, but with the Long Conference coming up next Tuesday, the justices may want to get this off their plates this week. Either way, it seems likely that there will be at least three votes on each side—and so the question, as is so often the case these days in politically charged cases, is where the Chief Justice and Justices Barrett and Kavanaugh end up. And here, that’s most complicated for Kavanaugh.

SCOTUS Trivia: Alabama’s Three Justices

By far, the most famous justice appointed to the Court from Alabama has to have been Hugo Black—a Democratic Senator appointed by FDR in 1937, who served all the way until retiring eight days before his death (and 52 years ago yesterday) in September 1971. There are a lot of crazy Black stories and statistics, but here’s my favorite piece of Court-related trivia: Black served as the senior associate justice for the last 26 years of his tenure—from the retirement of Justice Owen Roberts in July 1945 until Black’s own retirement. That is a record, and by a fair amount.

Constitutional Law scholars may be able to name one of Alabama’s other two justices: John Campbell was appointed to the Court by President Franklin Pierce in April 1853, and resigned in April 1861 to take a position in the Confederate government—the only southern justice to do so. I’ll confess, though, that I had to look up who the third Alabama justice was: John McKinley, also an Alabama Senator at the time of his appointment to the Court by President Van Buren in January 1838, who served until his death in July 1852. And to tie some threads together, McKinley was the first person appointed to one of the two new seats created by Congress in 1837 when it first expanded the Court to nine seats—a seat held today by Justice Samuel Alito.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone next Monday!

Happy Monday, everyone. I hope that you have a great week!!

The linked tweet notes the first *nine* Biden administration applications. There were two more in the interim—successful applications in the “ghost guns” and Purdue Pharma bankruptcy cases.

Kavanaugh is smart enough to know what he was doing when he wrote the concurrence. Sad that he didn’t just let the Chief’s opinion stand on its own.

Now Alabama gets another chance to discriminate against minority voters in their state. White supremacy continues.

Kavanaugh's gimmick is to repeatedly include these possible poison pills and given he was the fifth vote to hold things up until after the election it is more noticeable here.

Oh well. I guess we just have to trust the car thieves to drive the car a bit less recklessly.