43. The Supreme Court's Budget

A closer look at the Supreme Court's FY2024 appropriations request provides a useful reminder of how little the Constitution says about Congress's power of the purse

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it with your networks (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

From a litigation perspective, it was another quiet week at One First Street; there wasn’t a single order issued by the full Court. Instead, the biggest Court-related news of the week came Thursday, with the release of Justice Alito’s and Justice Thomas’s financial disclosure reports for 2023 (and, in the case of Justice Thomas, a series of amendments to prior reports). Those developments have been well-covered elsewhere. And at this point, writing yet another piece about how all of this underscores the need for some kind of neutral oversight mechanism to provide objective assessments of the justices’ financial and ethical conduct seems … repetitive. Suffice it to say, Thursday’s developments are unlikely to either (1) reduce the temperature surrounding these issues; or (2) move the needle in any meaningful direction toward any possible reforms.

The One First Long Read: We’d Like $150 Million, Please

Instead, I thought I’d use today’s newsletter as an excuse to do something that, candidly, I’ve never done before: To walk through the Supreme Court’s appropriations request (to Congress) for the upcoming fiscal year, which was part of the overall request submitted by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts on behalf of the federal judiciary back in March.

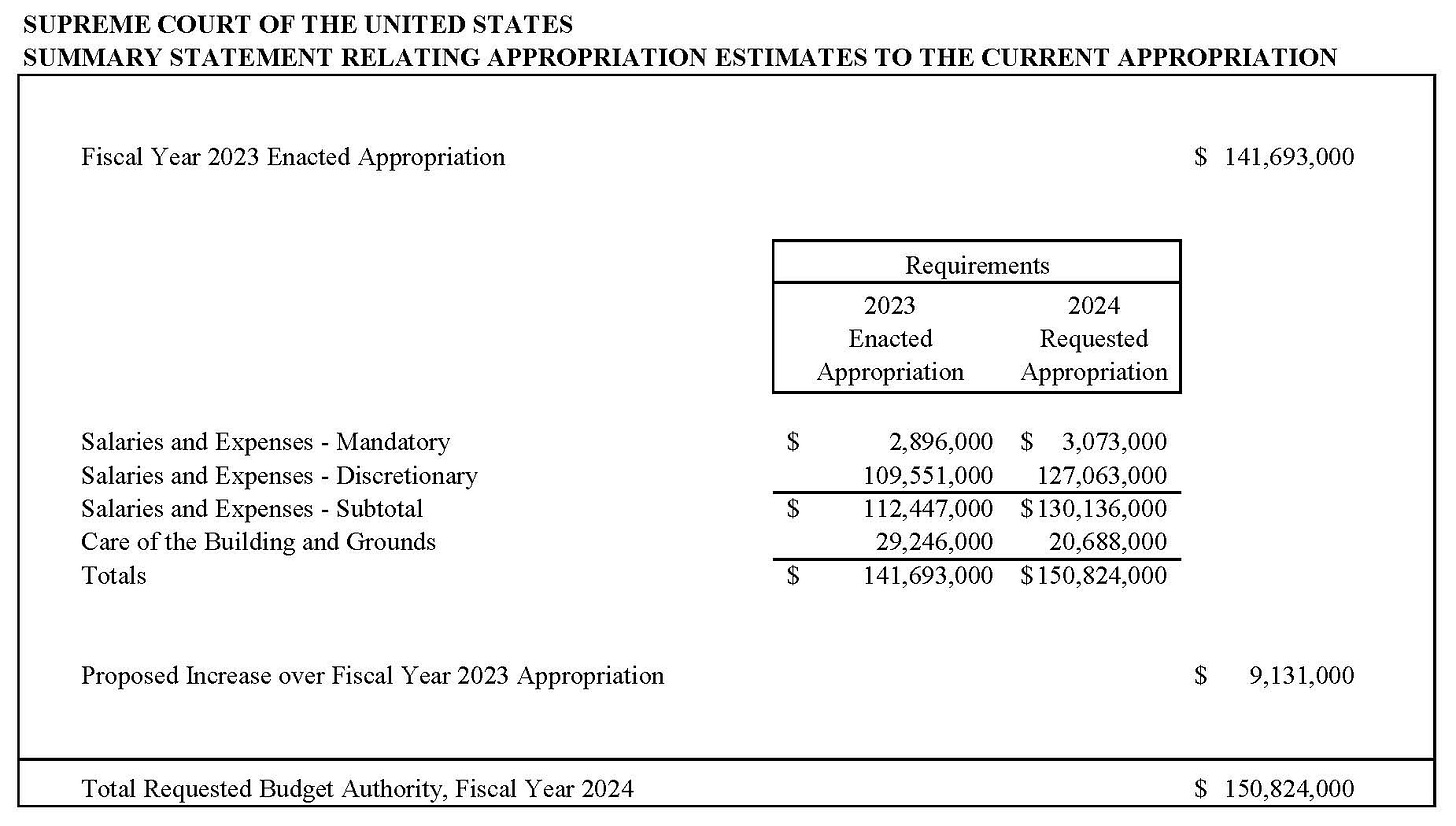

Folks should read the request (seeking a total appropriation of $150.8 million) for themselves; I’m going to pick out some of what (to me, anyway) are the key takeaways. (One note: The Court has two principal accounts: “Salaries and Expenses” and “Care of the Buildings and Grounds.” The overall request encompasses both, although they are broken out separately, so the FY2024 request includes $130.1 million for “Salaries and Expenses” and $20.7 million for “Care of the Buildings and Grounds.”)

First, the Court depends upon discretionary appropriations for the overwhelming majority of its budget. The “mandatory” appropriation to cover the nine justices’ salaries (which, under Article III of the Constitution, cannot be diminished) accounts for roughly $3 million—out of a total request of more than $150 million. (That’s < 2% of the total.) Without even getting into whether/when it’s appropriate to treat cost-of-living or other statutory pay adjustments as part of the mandatory appropriation, this is a rather important data point.

Second, and related, filing fees do very little work in defraying the Court’s costs. Even generously assuming that there are 2000 “paid” cases filed during a given Term (and that the $300 fee is paid in all of those cases), both of which are not true, that would generate only $600,000 in revenue—just over 0.5% of the Court’s appropriation request. In other words, even the sloppiest, back-of-the-envelope math suggests that the Court depends upon discretionary appropriations for well north of 95% of its operating budget.

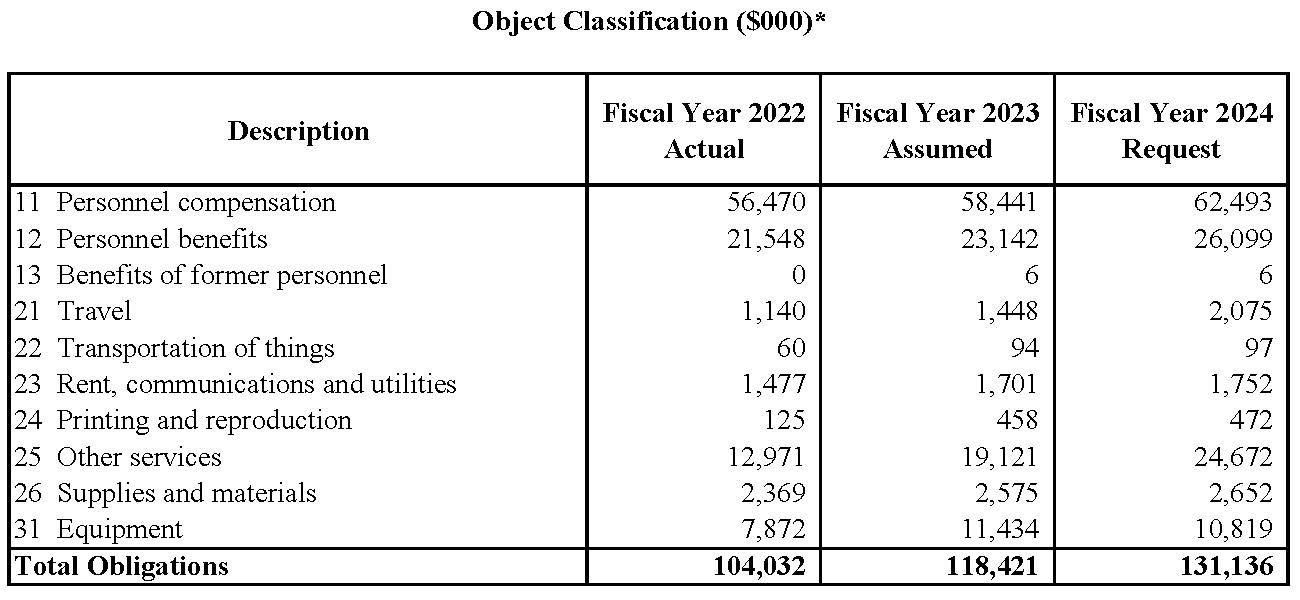

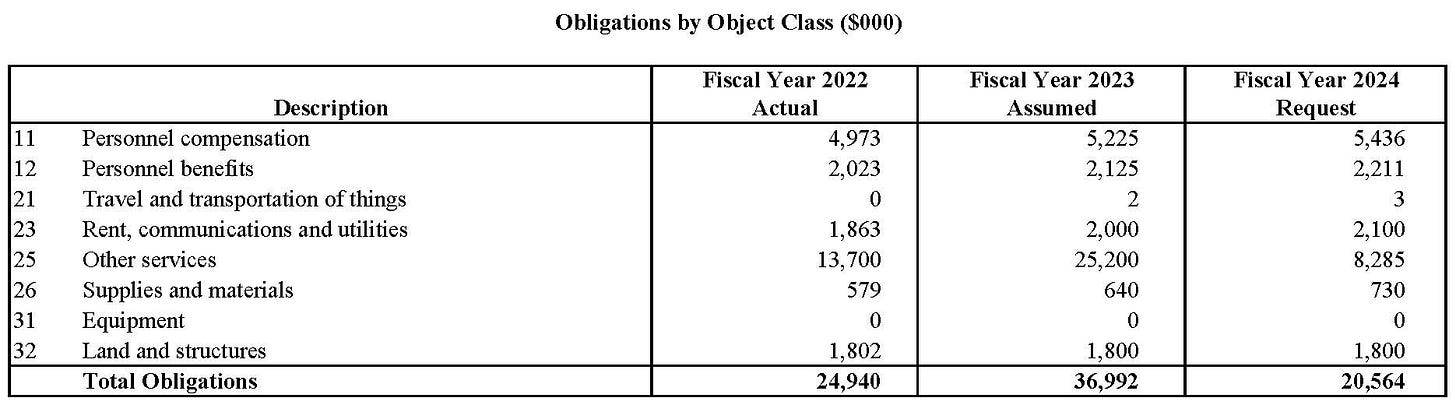

Third, although I’m embarrassed to admit that I never knew this number, the Court currently has 577 full-time employees besides the nine justices (to be perfectly honest, I would’ve guessed a total in the low 300s). 527 of those FTEs are covered by the “Salaries and Expenses” account; another 50 are covered by the “Buildings and Grounds” account. If I’m reading the charts correctly, compensation and benefits for the Court’s workforce, on the whole, account for roughly $96.1 million (or roughly 64%) of the total appropriations request. The other major categories across the two accounts include “Other Services” ($33.0 million); and “Equipment” ($10.9 million). Here are the “Obligations” tables from the two different accounts breaking out the expected obligations by category (I’m using the sum of lines 11 and 12 to generate the totals):

Fourth, the most significant increases from the FY2023 request to this year all appear to be security related, including an additional $6.5 million for “physical security improvements” and an additional $5.9 million for “expansion of protective activities.” As the request describes, “This request would expand security activities conducted by Supreme Court Police to protect the Justices. On-going threat assessments show evolving risks that require continuous protection.”

Fifth, the most significant decrease from the FY2023 request to this year involves the Buildings and Grounds account, where the request is for $18.7 million less than last year—as the Court nears the completion of a multi-year “Courtyard Restoration” project.

Sixth, and finally, the Court tends to receive most of what it asks for. The FY2023 request asked for a total of $143.6 million. Congress actually appropriated $141.7 million (98.7% of the request). And last year does not appear to have been an aberration in this respect. So as a general matter, Congress tends to effectively rubber-stamp the Supreme Court’s appropriations request (often holding pro forma and non-contentious hearings at which at least some of the justices will publicly testify). In other words, the Supreme Court’s appropriations process is not currently seen as a vector for meaningful oversight and accountability—in fairly sharp contrast to, for instance, appropriations hearings for executive branch departments.

I may have missed other big headlines in going through these materials (I wouldn’t pretend for a moment to be an expert on the appropriations process, or on the tables generated for these reports). But these strike me as among the more significant points for those who might care to pay attention to how the Court is funded.

Finally, none of this is meant as a criticism of the Court, or of its budget request. I offer the above only to provide analytical support for an anecdotal point that I’ve made previously: The Supreme Court is dependent upon Congress (and the President) to a degree that we do not often appreciate, and that the justices seldom admit. And the budget is perhaps the single most significant recurring source of that dependency—given how difficult it would be for the Court to function without a significant portion of its annual appropriations request. And it’s also the only part of that dependency that requires affirmative annual action by Congress (versus measures that Congress could, but doesn’t have to, adopt).

Reasonable minds can and will disagree over the extent to which Congress should use the Court’s budget as leverage for other reforms of the Court; what can’t be denied is that, as the above descriptions suggest, nothing in the Constitution would stop Congress from doing so if it wanted to. And given the Court’s regular dependence upon Congress’s provision of discretionary appropriations, such efforts would likely be far more than symbolic.

SCOTUS Trivia: Veterans’, Seamen, and Military Appeals

As I noted above, the filing fee for “paid” cases in the Supreme Court is $300. That amount is set by the Clerk of the Court. (Cases in which a prisoner proceeds “in forma pauperis” don’t require a filing fee.) But there are three categories of “paid” cases in which a non-prisoner is exempted by statute from paying the filing fee:

“A veteran suing to establish reemployment rights under 38 U.S.C. § 2022, or under any other provision of law exempting veterans from the payment of fees or court costs”;

“A seaman suing under 28 U.S.C. § 1916”; or

“An accused person petitioning for a writ of certiorari to review a decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces under 28 U.S.C. § 1259.”

And although veterans and seamen must formally move the Court to be deemed as such (and thus exempt from paying filing fees), servicemembers challenging decisions of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces are the only parties automatically exempted from the $300 fee.

(I told you it was trivia!)

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers (the September installment of “Karen’s Corner”) will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone next Monday!

Happy Monday, everyone. I hope that you have a great week!!

Certainly one easy way for the Congress to put pressure on the court to adopt, say, a more adequate ethics standard would be to cut their travel budget and attach a rider prohibiting justices or staff from accepting outside funding for travel.

It is realistic to note that the release of the Alito and Thomas financial disclosures will not move the needle though in a just world it would, including Thomas' rub our faces in it hiring someone to release a blatantly partisan statement defending himself.