42. The Switch in Time That Saved Nine

The conventional view is that FDR's 1937 "court-packing" plan failed. But his attacks on the Supreme Court may have had a lot to do with one of the most consequential doctrinal shifts in its history.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it with your networks (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

It was another quiet week at the Court, with just the second (of three) summer order lists coming down last Monday. (None of the orders were especially noteworthy.) And at least at this writing, there are no significant pending emergency applications likely to generate rulings this week. The quiet week provides a good excuse for a more historically driven post, hence this week’s focus on the “switch in time.”

The One First Long Read: FDR vs. the Court

Among the rulings the Supreme Court handed down on Monday, March 29, 1937, was its decision in West Coast Hotel v. Parrish, in which a 5-4 majority rejected a due process challenge to Washington state’s law setting a minimum wage for women and minors. But the significance of West Coast Hotel wasn’t its result; it was the fact that Chief Justice Hughes’s majority opinion not only upheld Washington’s law; it rejected the judicial skepticism of economic regulation that had come to characterize the Court’s jurisprudence for much of the preceding three decades—dating back to the 1905 ruling in Lochner v. New York.

The “Lochner era” had seen the Court aggressively police economic regulation at both the state and federal level, including a series of decisions in the mid-1930s that had thrown a wrench in the New Deal. Most recently, in June 1936, the Court had struck down New York’s minimum wage law for women, relying on a 1923 decision that was itself suffused with Lochner-like reasoning.

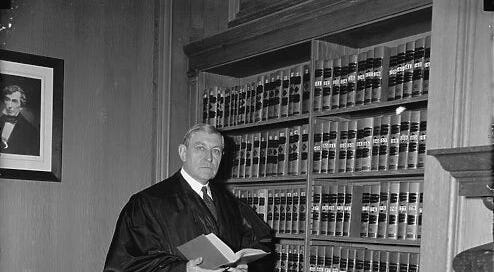

What made West Coast Hotel such a big deal was the vote of Justice Owen Roberts—who joined the majority without comment. Roberts had consistently been a fifth vote with the four conservative justices (nicknamed the “four horsemen of the apocalypse”) in striking down state economic regulations and federal New Deal programs, including in the New York case the previous June. By not just flipping, but signing on to Chief Justice Hughes’s broad endorsement of judicial deference to economic regulation, Roberts appeared to augur the end of the Lochner era—and the beginning of what’s often described as “modern constitutional law.” Within a year, the Court would hand down a slew of major constitutional decisions recognizing expanded federal regulatory powers over everything from Social Security to workplace conditions; establishing the modern “rational basis” test enshrining deference to democratically elected legislatures; and articulating, for the first time, a coherent framework for the exceptional circumstances in which heightened judicial scrutiny would be appropriate. There’s a reason why West Coast Hotel and its companion cases are often shorthanded as the “Constitutional Revolution of 1937.”

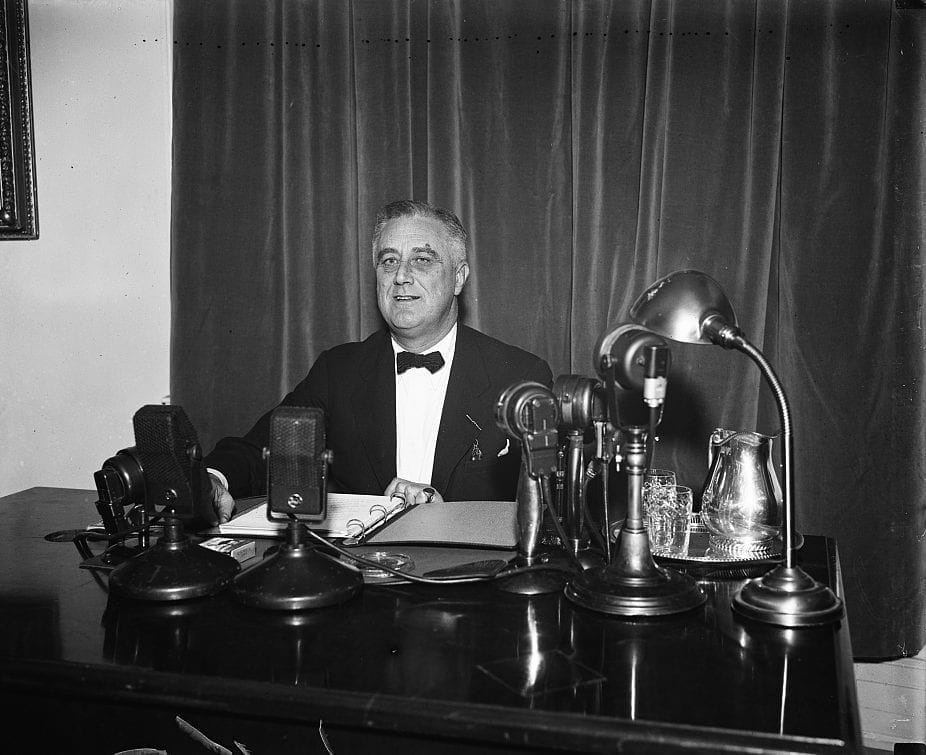

Borrowing from a sewing aphorism (“a stich in time saves nine”), the humorist Cal Tinney famously dubbed Roberts’s vote in West Coast Hotel “the switch in time that saved nine.” This was a widely understood reference to the relationship between the decision in West Coast Hotel and the demise of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s court-packing plan, which he unveiled on February 5, 1937—and defended in his ninth “Fireside Chat” on March 9, 1937.

Among other things, FDR’s plan would have added a new judgeship for every active federal judge who was 70 or older—which, as applied to the Supreme Court’s six septua-(and octo-)genarians, would have expanded the size of the Court to 15 justices.

The heart of FDR’s plan1 was eventually scuttled by congressional Democrats, who dragged their collective heels rather than move the bill quickly through the legislature. But that defeat came months after West Coast Hotel, by which point it would have been clear to anyone watching the Court carefully (including FDR) that the impetus for packing the Court had largely dissipated. Not only had Roberts switched sides, but Justice Van Devanter retired on June 2, 1937 (after Congress restored the justices to full pensions), and Justice Sutherland would follow suit the following January—giving FDR his first two appointments to the Court in Justices Hugo Black and Stanley Reed, both of whom were staunch New Dealers. By the end of the October 1937 Term, the Court had a solid 7-2 majority sympathetic to the New Deal and the Court’s new framework for constitutional adjudication. And by July 1941, eight of the nine justices (everyone except Roberts) had been appointed to their seats by FDR.2

Thus, Tinney’s famous quip captured what became the conventional understanding: That Roberts switching his vote directly contributed to the demise of FDR’s court-packing plan if for no other reason than because Roberts’s about-face had mooted the need for it. His “switch in time” in West Coast Hotel “saved” a nine-justice Court from FDR’s machinations.

There seems to be little question about this causal relationship. We’ll never know whether congressional Democrats would have stood up quite as aggressively to FDR if the Court had shown no signs of moderating its position, but it seems clear that at least some of the institutional backbone coming from Capitol Hill could be attributed to the reduced need for the proposed reforms once the decision in West Coast Hotel signaled the shift that its analysis precipitated. FDR, too, stopped putting quite as much effort into getting his reforms through as the Court appeared to be moderating its views.

The bigger debate, it turns out, is why the switch happened at all. Was it the court-packing plan that led Roberts to blink? Or is that just one of history’s coincidences?

To be sure, the decision in West Coast Hotel came more than seven weeks after FDR introduced his reform bill—and 24 days after the March 5 fireside chat. So at least in the strictest chronological sense, Roberts’s switch did follow the publicization of, and public debate surrounding, the court-packing plan. But it is clear from the papers of other justices that Roberts initially voted to uphold Washington’s law at the Court’s Conference after oral argument in West Coast Hotel—on December 19, 1936. Roberts could have changed his mind between then and when the decision was handed down on March 29; the key is that the “switch” so central to West Coast Hotel clearly pre-dated the public rollout of FDR’s court-packing plan. Thus, those inclined to see no connection between these events typically point to this timeline to suggest that, whatever the reason for Roberts’s change of heart, it wasn’t FDR.

I certainly agree with the (irrefutable) claim that the “switch” came in December 1936, not March 1937, and so can’t be cast as a direct response to FDR’s proposal to give Roberts six new colleagues. As Justice Felix Frankfurter would later write,

It is one of the most ludicrous illustrations of the power of lazy repetition of uncritical talk that a judge with the character of Roberts should have attributed to him a change of judicial views out of deference to political considerations. ... Intellectual responsibility should, one would suppose, save a thoughtful man from the familiar trap of post hoc, ergo propter hoc.

But before giving up on any connection between FDR and Roberts’s switch, it’s worth putting the Election of 1936 into context.

By 1936, FDR was a tremendously popular president. Even though the Supreme Court had reined in a number of his New Deal policies, they remained massive sources of public support, so much so that his Republican opponent, Kansas Governor Alf Landon, largely agreed with the central features of FDR’s program. In reality, FDR ended up running as much against the Supreme Court in 1936 as he did against Landon. After the Court had struck down New York’s minimum wage law for women on June 1, Roosevelt described the justices as creating a “‘no-man’s-land’ where no Government—State or Federal—can function.”

In every respect, FDR’s 1936 campaign was a massive success. He won 46 of 48 states (resulting in a rather lopsided 523-8 margin in the Electoral College); received the highest share of the national popular vote since James Monroe’s effectively uncontested re-election in 1820; and swept a number of liberal Democrats into office on his coattails. Thus, by November 1936, it was obvious that FDR had a sizeable electoral mandate, a significant part of which rested on opposition to the Supreme Court.

Roberts would not have been oblivious to either the general tenor of FDR’s campaign or his specific quips about the Court. Indeed, it seems entirely possible that, without any foreknowledge of a specific plan to add justices to the Court, Roberts understood that the Election of 1936 was at least to some degree a referendum on the Court’s hostility to the New Deal to that point in time. That’s not enough to prove that he switched his vote in West Coast Hotel in response to the election result, or the hostility to the Court that it reflected. But the insistence by Frankfurter and other Roberts defenders that his move had absolutely nothing to do with the broader political atmosphere is hard to accept without a persuasive alternative justification. Even Chief Justice Hughes, who was adamant that there was no connection between West Coast Hotel and the court-packing plan, was a bit more circumspect about the role of public influence on the Court more generally. In 1936, he wrote that, when the Court departed from "its fortress in public opinion,” it tended to suffer from self-inflicted wounds.

Thus, although the conventional wisdom is that FDR’s court-packing plan failed, I teach it in my classes as being a fair bit more complicated. Roberts himself would write, after retiring, that “Looking back, it is difficult to see how the Court could have resisted the popular urge for uniform standards throughout the country—for what in effect was a unified economy.” Given what happened at the ballot box in November 1936, that “popular urge” sure seems to have had more than nothing to do with the “switch in time” (and all of the doctrinal shifts that followed). And although that popular urge had the ultimate effect of undermining what would have been one of the most contentious legislative reforms to the Supreme Court in its history, it may have done so only by knocking the Court off its anti-New Deal perch. Not for the first time, and not for the last, the Court’s relationship with the public (and the public’s relationship with the Court) looms large over even the Court’s substantive decisionmaking.

SCOTUS Trivia: A President’s Court

This one will be easy, but it seemed impossible not to include given the topic of this week’s Long Read. As noted above, by July 1941, FDR was responsible for filling eight of the Court’s nine seats. As it would turn out, he never got to fill the ninth; Justice Roberts would not resign from the Court until July 31, 1945—three and a half months after FDR’s death.

Instead, the only President who appointed justices to every seat on the Court was, quite obviously, President Washington—who got to name not just the first six justices, but five more after that.

For two more challenging trivia questions, how about:

Who was the first justice appointed by a President other than Washington?

After Washington (11) and FDR (9), which President appointed the third-most justices?

The answer to the first question is … Washington! (Bushrod Washington, George’s nephew, who was appointed by President Adams in 1798 to succeed Justice Wilson, and would serve for more than 31 years.)

The answer to the second question might come as a bit of a surprise, especially because he served only one term as President: Future Chief Justice William Howard Taft, who appointed six justices to the Court in four years (the last of whom to leave the Court was, bringing things full circle, Van Devanter).

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone next Monday!

Happy Monday, everyone. I hope that you have a great week!!

Part of FDR’s plan actually did make it into law—significantly expanding the types of cases that had to be heard in the first instance by three-judge district courts, rather than individual federal judges (as a way of reducing the ability of outlier individual judges to block federal programs).

This includes now-Chief Justice Stone, who was elevated from the ranks of Associate Justice by FDR upon Chief Justice Hughes’s June 1941 retirement.

I actually think FDR's court-packing plan made sense--he didn't add a justice whenever another reached 70 but when that justice refused to retire. It was a good way of keeping the "life time appointment" permissible because there is nothing that says a justice can't cut his appointment short by retiring. Nowadays, the age would have to be rather older.

Why did Congress reject it? I suspect in part because despite its unpopular decisions, it was still seen as a respectable institution, even revered. As far as I know, there wasn't a constant stream of scandal involving money grubbing justices. (I have no idea whether there was a recusal problem). The rule of law has ALWAYS involved respecting as a matter of law the majority opinions of the justices even if you disagree with those opinions, so long as the justice gives arguable reasons and doesn't appear to be personally corrupt. The response is to try to find workarounds via Congress that meet the objections of the court. And at LEAST the FDR court invoked the sense of predictability that goes along with adherence to precedent until at least some justices realized that a tipping point had been reached, with precedent both unpopular and actually hurtful to the country as a whole. (I'm not saying that happened with Roberts, but as an example of the respect felt for the court).

We don't live in that world today.

Thanks for a concise explanation of the “switch in time”. I haven’t read a better one.