41. The Supreme Court and the Federal Officer Removal Statute

A quick and dirty overview of how the federal officer removal statute, as interpreted by the Court, maps onto the latest indictment of former President Trump on state criminal charges in Georgia

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it with your networks (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

After the flurry of activity the previous week, last week was pretty quiet at the Court. There was only a single order of the full Court (denying the ACLU of Florida’s application to vacate a lower-court stay in litigation over districting in the City of Miami), along with a handful of emergency applications that were denied in chambers. And at least for now, there are no pending applications likely to lead to action by the full Court this week, so there may well be another quiet week in store.

The One First Long Read: Federal Officer Removal

The latest indictment of former President Trump—on a broad array of state criminal charges in Fulton County, Georgia—has, among other things, brought a lot of interest to the scope of an obscure but important federal law known informally as the “federal officer removal statute,” whether it allows for the removal of some or all of the prosecution from state court to federal court, and what happens if and when some or all of the case is removed.

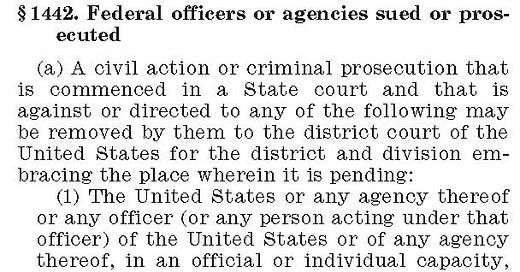

The statute, which dates in some form all the way back to 1815 and is codified today at 28 U.S.C. § 1442, provides a mechanism through which federal officers who are defendants to civil or criminal suits in state courts can remove the case to federal court. (My thanks to University of Texas 2L Isabella Sofroniou for helping with some of the research related to today’s post.)

As relevant here, the central provision, § 1442(a)(1), authorizes removal of any civil or criminal suit against

The United States or any agency thereof or any officer (or any person acting under that officer) of the United States or of any agency thereof, in an official or individual capacity, for or relating to any act under color of such office or on account of any right, title or authority claimed under any Act of Congress for the apprehension or punishment of criminals or the collection of the revenue. [emphasis mine]

In other words, the text of the statute adopts a fairly broad causal connection between the suit and the removal—appearing to authorize removal so long as the suit “relate[s] to any act under color of” the defendant’s federal office. (That’s why, among other things, there’s little question that the statute can be invoked by former federal officers if the lawsuit relates to conduct undertaken while they were in office.)

As Justice Marshall wrote for the Court in 1969, this textual breadth is supported by the historical evolution of the statute:

The federal officer removal statute has had a long history. The first such removal provision was included in an 1815 customs statute. It was part of an attempt to enforce an embargo on trade with England over the opposition of the New England States, where the War of 1812 was quite unpopular. It allowed federal officials involved in the enforcement of the customs statute to remove to the federal courts any suit or prosecution commenced because of any act done ‘under colour’ of the statute. Obviously, the removal provision was an attempt to protect federal officers from interference by hostile state courts. This provision was not, however, permanent; it was by its terms to expire at the end of the war. But other periods of national stress spawned similar enactments. South Carolina's threats of nullification in 1833 led to the passage of the so-called Force Bill, which allowed removal of all suits or prosecutions for acts done under the customs laws. A new group of removal statutes came with the Civil War, and they were eventually codified into a permanent statute which applied mainly to cases growing out of enforcement of the revenue laws. Finally, Congress extended the statute to cover all federal officers when it passed the current provision as part of the Judicial Code of 1948.

All along, the purpose of these statutes has been quite clear, as the Court explained in 1880:

[The federal government] can act only through its officers and agents, and they must act within the States. If, when thus acting, and within the scope of their authority, those officers can be arrested and brought to trial in a State court, for an alleged offence against the law of the State, yet warranted by the Federal authority they possess, and if the general government is powerless to interfere at once for their protection,—if their protection must be left to the action of the State court,—the operations of the general government may at any time be arrested at the will of one of its members.

Thus, in that 1969 case (Willingham v. Morgan), the Supreme Court interpreted the “under color of such office” language capaciously—holding that it was enough for defendants to show that the underlying dispute arose “while they were performing their duties” inside a federal penitentiary. In so holding, the Court rejected a narrower standard that would have limited removal to cases in which the federal officers were immune from state litigation. Willingham thus appears to suggest, at first reading, that federal officer removal is virtually unbounded—so long as the underlying state court proceeding seeks relief against defendants related to the performance of their official duties as federal officers. If that’s where the Court had left things, it might be fairly obvious that at least some of the defendants in the Georgia indictment (those who held formal positions in the federal government) can remove their prosecutions to federal court.1

But there are two caveats that may bear upon the Georgia case—and they both come from the Court. Willingham itself articulated the first one: “Were this a criminal case,” Justice Marshall wrote in a footnote, “a more detailed showing might be necessary because of the more compelling state interest in conducting criminal trials in the state courts.” Thus, Willingham suggested that it might not be enough, in a criminal case, for federal officers to simply assert that the alleged offenses arose out of the performance of their official duties; they might need to show how the offenses truly do relate to those duties (which could be a real sticking point when it comes to a prosecution arising out of efforts to undermine the 2020 election results in Georgia).

The bigger caveat comes from a subsequent decision by the Court: The 1989 ruling in Mesa v. California. In Mesa, the Court grappled with a constitutional question raised by Willingham’s capacious reading of the removal statute: What is the constitutional basis for federal courts exercising subject-matter jurisdiction over a state-law dispute that begins in a state court? As Justice O’Connor held for a unanimous Court, the answer is that the statute only authorizes removal once the officer-defendants have raised a federal defense. It’s not enough that the suit “relate to” the performance of their federal duties; the officers themselves must raise an argument grounded in federal law for why the suit can’t go forward. In her words:

Section 1442(a), in our view, is a pure jurisdictional statute, seeking to do nothing more than grant district court jurisdiction over cases in which a federal officer is a defendant. Section 1442(a), therefore, cannot independently support Art. III “arising under” jurisdiction. Rather, it is the raising of a federal question in the officer’s removal petition that constitutes the federal law under which the action against the federal officer arises for Art. III purposes. The removal statute itself merely serves to overcome the “well-pleaded complaint” rule which would otherwise preclude removal even if a federal defense were alleged. Adopting the Government's view would eliminate the substantive Art. III foundation of § 1442(a)(1) and unnecessarily present grave constitutional problems. We are not inclined to abandon a longstanding reading of the officer removal statute that clearly preserves its constitutionality and adopt one which raises serious constitutional doubt.

Thus, in addition to the “causal connection” question, the statute also requires the removing defendants to invoke some federal law basis that, if successful, would defeat the state claims. The defense doesn’t have to succeed in order for the removal to occur, but removal depends upon a non-frivolous federal claim that could end up being dispositive. Mark Meadows, for instance, has already moved to dismiss the indictment against him (which he was the first to remove to federal court) on the grounds that (1) he has “Supremacy Clause immunity”; and (2) defenses under the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

In some respects, Meadows may have the easiest case for removal, since he was acting as Trump’s Chief of Staff at the time of his allegedly unlawful conduct. Many of the other defendants may have a harder time, either because they were never federal officers in the first place, or because they were in a position in which efforts to interfere with the results in Georgia can’t in any way be tied to the official duties of their office. But perhaps the real takeaway here is that removal is largely a sideshow. Whether all or just some of these cases end up in federal court, it would be (1) the same prosecutors; (2) the same offenses; and (3) an overlapping (albeit not similar) jury pool. Like any other case removed to federal court, it doesn’t become a federal case because of the removal, meaning that these offenses remain outside the scope of the President’s pardon power. Instead, the real fighting is likely to turn on claims like those advanced in Meadows’ motion to dismiss, including whether “Supremacy Clause immunity” insulates from criminal liability efforts to undermine a presidential election.

SCOTUS Trivia: Justices and Inaugurations

This month marks the 100th anniversary of the swearing in of President Calvin Coolidge by his father—a Vermont notary public and justice of the peace (then-Vice President Coolidge was vacationing in Vermont when President Warren G. Harding died on August 2, 1923). There’s a small list of individuals who have sworn in presidents under similarly macabre circumstances (perhaps most famously, Judge Sarah Hughes swearing in Lyndon Baines Johnson in Dallas on November 22, 1963), in contrast to the norm of having the President sworn in by the Chief Justice of the United States. There’s also the only non-Chief Justice to swear in two presidents (William Cranch, Chief Judge of the old D.C. Circuit, who swore in both President Tyler after President Harrison’s death in 1841, and President Fillmore after President Taylor’s death in 1850).

This led me to wonder whether any Supreme Court justice other than the Chief Justice has ever sworn in a president. And the answer, perfect for trivia, is that it’s happened exactly once.

The only Associate Justice to ever swear in a president was Justice William Cushing, who delivered the oath to President George Washington at the beginning of his second term on March 4, 1793, in Philadelphia. Washington, who, the story goes, wanted his second inauguration to be a low-key affair, gave a 135-word speech (the shortest inaugural address in American history by a fair margin), after which he was sworn in by one of the Circuit Justices with geographic responsibility for Pennsylvania—Cushing. The tradition of having the Chief Justice deliver the oath at quadrennial inaugurations began four years later—when Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth swore in President John Adams. And it has been unbroken ever since.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone next Monday!

Happy Monday, everyone. I hope that you have a great week!!

Unlike removal of civil cases, where it’s clear that the entire suit is removed so long as one defendant removes, the rules for removal of criminal cases are unsettled. It is possible that it’s sufficient for a single defendant to satisfy the federal officer removal statute for the entire case to be removed to federal court, but it’s not self-evident.

Can you explain why Meadows has “supremacy clause immunity?” Wouldn’t there have to be a federal statute that says it is ok to plot to overthrow the government? If the issue is the broader Federal RICO law, how does that in itself grant “immunity?” Can Willis end run that by simply taking him out of the RICO part of the case and charge him just with conspiracy under state law?

"But perhaps the real takeaway here is that removal is largely a sideshow."

A sideshow it may be, but as a delaying tactic, it's another opportunity for indictees to slow-walk legal proceedings against them. Let's see how expeditiously the federal district judge hearing the case, Steve Jones, handles the motion, no doubt the first of several to be filed, including one by tRump himself. Also, if the judge rules against the remove motion, is it appealable?