37. The Mountain Valley Pipeline and United States v. Klein

With the notoriously vague 1872 ruling at the heart of the current dispute over the Mountain Valley Pipeline, a look at why the "rule" of Klein is so elusive—but also so important

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it with your networks (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

A little before 1:30 a.m. ET on Friday, the justices handed down their first order of the summer—and it was a doozy. The Court turned away a last-minute request for a stay of execution from Alabama death row prisoner James Edward Barber, who charged that the state, which has had repeated and notorious issues carrying out its execution protocol in at least three recent cases, had done nothing to reduce the risk that his execution, too, would be botched—in violation of his rights under the Eighth Amendment. Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson publicly dissented—with the latter two joining Justice Sotomayor’s testy, 11-page dissent from the denial. Quoting Judge Jill Pryor’s dissent from the Eleventh Circuit’s denial of a stay, Sotomayor wrote that: “Alabama plans to kill [Barber] by lethal injection in a matter of hours, without ever allowing him discovery into what went wrong in the three prior executions and whether the State has fixed those problems. The Eighth Amendment demands more than the State’s word that this time will be different. The Court should not allow Alabama to test the efficacy of its internal review by using Barber as its ‘guinea pig.’”

In keeping with their recent approach to other last-minute execution-related claims, though, at least five of the other justices allowed just that.

This week, we expect a ruling, one way or the other, on the Mountain Valley Pipeline’s emergency application to vacate three stays issued by the Fourth Circuit—stays which are, for the moment, preventing completion of the pipeline. Chief Justice Roberts called for responses by 5:00 p.m. tomorrow (Tuesday). With the Fourth Circuit currently scheduled to hear oral argument in the disputes this Thursday, it’s a decent bet that we’ll hear from the Court (or from the Chief Justice, acting on his own) sometime Wednesday. As for why that dispute is so fraught, well, read on.

The One First Long Read: Klein and the Judicial Power of the United States

As noted above, the Court is expected to rule this week on an emergency application in the Mountain Valley Pipeline case, a dispute in which the current litigation turns on the constitutionality of section 324 of the debt ceiling bill. In a nutshell, section 324 makes a bunch of findings about the pipeline, strips jurisdiction over most remaining challenges to the pipeline, and then confers exclusive jurisdiction over challenges to the constitutionality of section 324 in the D.C. Circuit, a not-so-subtle effort led by West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin to take these cases away from the Fourth Circuit.

The constitutional question raised by section 324 is whether Congress has gone too far in telling the courts how to do their job. And the best (really, only) case that the pipeline’s challengers have to support the argument that Congress has crossed the line is United States v. Klein—an important but notoriously elliptical 1872 decision. In the post that follows, I walk through (1) Klein’s background; (2) Klein’s holding and subsequent interpretation; and (3) how that ought to cash out in the Mountain Valley Pipeline case. Just to spoil things for you, my own view is that (1) Klein articulates a very important limit on Congress’s power over the federal courts; (2) section 324 doesn’t transgress that limit; and (3) even if part of it does, a different part deprives the Fourth Circuit (as opposed to the D.C. Circuit) of the jurisdiction to say so.

I. Klein’s Background

To understand Klein, we have to begin with the Captured and Abandoned Property Act of 1863. In that statute, among lots of other things, Congress sought to deal with the problem of providing for restitution for property seized by the Union Army and sold and/or destroyed by the federal government during the Civil War. Critically for present purposes, one of the conditions Congress imposed upon recovery under the act (in section 3) was for the claimant to demonstrate that he had “never given any aid or comfort to the present rebellion”—in essence, that he had remained loyal to the Union throughout the Civil War. After all, Congress, especially in March 1863, was hardly interested in helping to make Confederate supporters whole.

Fast forward to April 30, 1870—and the Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Padelford. Edward Padelford, a Savannah banker, sought to recover under the 1863 act for his share of cotton that was captured by the Union Army when General Sherman captured Savannah and subsequently sold at a handsome profit by federal Treasury agents. The federal government argued that Padelford had “given aid or comfort” to the rebellion because, among other things, he had purchased Confederate bonds during the war. Padelford’s response was to suggest that he had effectively been forced to support the Confederacy or risk his livelihood, but that, in any event, prior to the capture of his cotton, he had taken the oath of loyalty prescribed by President Lincoln in December 1863—which thereby pardoned him for the “aid and comfort” that would otherwise have disqualified him from recovery under the 1863 statute.

For a unanimous Court, Chief Justice Chase sided with Padelford. Not only did the Court hold that Padelford’s pardon established that he had not “given aid or comfort” to the Confederacy for purposes of the Captured and Abandoned Property Act; it also concluded that the same result would follow even if his property had been captured first—and he had taken the oath only after the fact. As Chase wrote, “It follows that at the time of the seizure of the petitioner's property he was purged of whatever offence against the laws of the United States he had committed by the acts mentioned in the findings, and relieved from any penalty which he might have incurred. It follows further that if the property had been seized before the oath was taken, the faith of the government was pledged to its restoration upon the taking of the oath in good faith.”

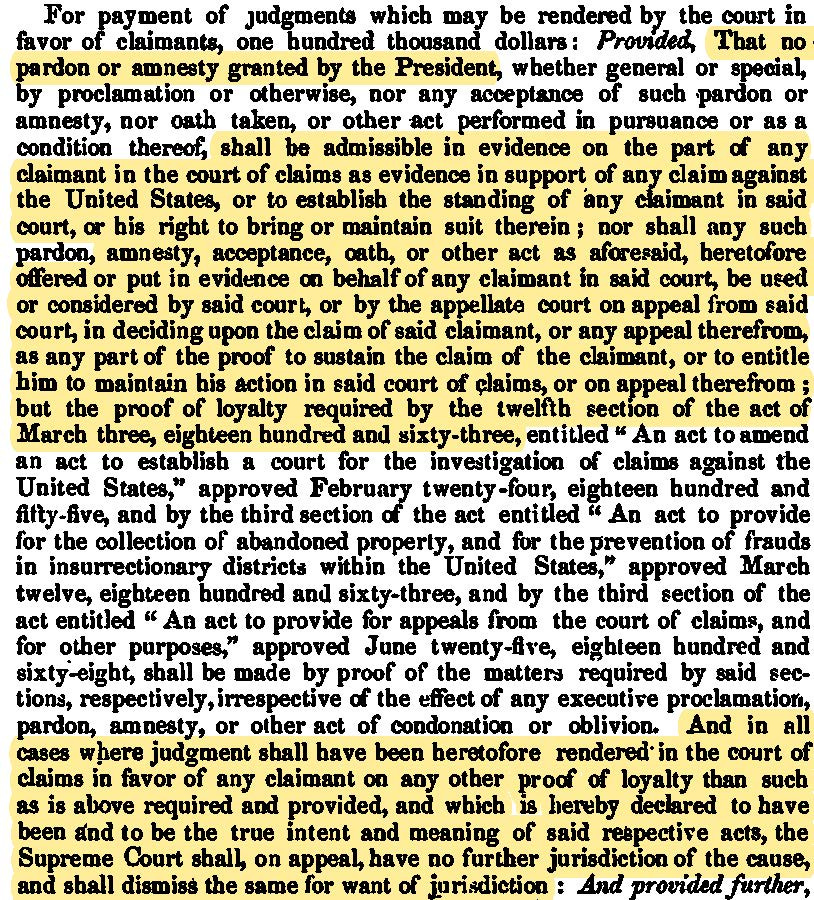

By April 1870, Congress was controlled by radical Republicans—who, in the midst of pursuing a more punitive version of Reconstruction than that championed by President Lincoln (let alone President Johnson), were none-too-pleased with the Supreme Court’s decision in Padelford. Taking the position that anyone who needed to subscribe to President Lincoln’s loyalty oath in the first place was necessarily disloyal for purposes of the Captured and Abandoned Property Act (after all, the statute dealt with those who had “never given aid or comfort”), Congress quickly tacked the following (wordy) proviso onto the annual federal government appropriations bill:

In other words, the 1870 appropriations proviso did two principal things: First, it purported to overrule Padelford, providing that, at least for purposes of the 1863 act and a handful of other similar statutes, taking the Lincoln oath was proof of the claimant’s disloyalty. Second, it deprived the Supreme Court of jurisdiction to resolve appeals in such cases—and then ordered those cases to be dismissed for want of jurisdiction.

II. Klein’s Holding

The question before the Supreme Court in United States v. Klein, argued on April 20 and 21, 1871, but not decided until January 29, 1872, was whether the 1870 proviso was constitutional. And for an (effectively) unanimous Court,1 Chief Justice Chase held that the answer was “no.” The tricky part is why. Here’s the key passage from Chase’s opinion:

the denial of jurisdiction to this court, as well as to the Court of Claims, is founded solely on the application of a rule of decision, in causes pending, prescribed by Congress. The court has jurisdiction of the cause to a given point; but when it ascertains that a certain state of things exists, its jurisdiction is to cease and it is required to dismiss the cause for want of jurisdiction.

It seems to us that this is not an exercise of the acknowledged power of Congress to make exceptions and prescribe regulations to the appellate power. The court is required to ascertain the existence of certain facts and thereupon to declare that its jurisdiction on appeal has ceased, by dismissing the bill. What is this but to prescribe a rule for the decision of a cause in a particular way? In the case before us, the Court of Claims has rendered judgment for the claimant and an appeal has been taken to this court. We are directed to dismiss the appeal, if we find that the judgment must be affirmed, because of a pardon granted to the intestate of the claimants. Can we do so without allowing one party to the controversy to decide it in its own favor? Can we do so without allowing that the legislature may prescribe rules of decision to the Judicial Department of the government in cases pending before it?

We think not . . . .

Chase went on to suggest, in the alternative, that the 1870 proviso also ran afoul of the President’s pardon power. But the Article II holding was clearly secondary (in Chase’s words, “The rule prescribed is also liable to just exception . . . .”). Instead, 153 years later, there’s still debate over this Article III holding—and what it prevents Congress from doing.

Consider two ends of the spectrum. At one end is Congress’s clear and unquestioned power to create both procedural and substantive “rules of decision,” i.e., rules that govern how a case should be resolved depending upon the parties’ compliance therewith. If Congress says a suit must be filed within two years of an injury, it has provided a “rule of decision” for suits filed any later than that. Ditto if Congress says a plaintiff must show malice to recover for certain torts, and the plaintiff fails to do so. No one seriously disputes that Congress can thus prescribe some “rules of decision” simply by creating procedural or substantive predicates for relief, even though those predicates will be dispositive in many cases.

At the other end is a statute that provides that, “in the pending lawsuit known as Jones v. Smith, the court shall rule for Jones.” That’s not prescribing rules for courts to apply; that’s applying the rule for the courts. Thus, I’ve always taught Klein to my (confused) Federal Courts students as standing for the proposition that Congress may not purport to exercise “the judicial power of the United States” by dictating not just rules that will require specific outcomes in specific cases, but by dictating the outcome directly. The difference lies, somewhat obtusely, in whether courts are allowed to find the predicate conditions for themselves before acting on the case—versus not. Klein is thus an easy example of its own rule because of the very end of the highlighted text above—”the Supreme Court . . . shall dismiss the same for want of jurisdiction.”

By that logic, the Supreme Court should have struck down the statute at issue in the most recent case in which it considered Klein—Patchak v. Zinke. In that 2018 dispute, Congress had provided that a disputed piece of property was “reaffirmed as trust land,” and that “an action . . . relating to [that] land shall not be filed or maintained in a Federal court and shall be promptly dismissed.” Indeed, in an amicus brief on behalf of a group of Federal Courts professors that I drafted and filed along with my friend Lindsay Harrison from Jenner & Block, we argued that the statute was a textbook violation of Klein because of how it directed the outcome without changing the governing procedural or substantive rules.

The Supreme Court disagreed, but without a majority opinion. Justice Thomas’s opinion for a four-justice plurality (including Justices Breyer, Alito, and Kagan) embraced an incredibly narrow view of Klein—suggesting that it really did turn on the alternative pardon power holding. Chief Justice Roberts’s dissent, joined by Justices Kennedy and Gorsuch, would have held that the statute was unconstitutional largely for the reasons we advanced in our amicus brief. But critically, so too would Justices Ginsburg and Sotomayor, who both concurred in the judgment on remarkably narrow grounds. In their view, although the statute at issue in Patchak would be unconstitutional in most cases, it was valid in Patchak entirely because it came as part of a waiver of the federal government’s sovereign immunity—a context in which Congress is allowed to impose conditions that would otherwise be invalid.

In other words, as recently as 2018, there were five votes for the proposition that a statute directing the courts in how to exercise their judicial power—and not just in giving them rules to apply—would violate the separation of powers. It’s hard to say where the three new justices appointed since Patchak would fall along those lines, but I have to think at least two of them (and perhaps all three) would agree. If so, then the best way to understand the “rule” of Klein is as distinguishing between procedural and substantive rules that may end up dictating outcomes in many (if not most) cases and outcomes that Congress dictates directly. That won’t always be an easy line to draw, but just because it is elusive doesn’t mean that it’s illusory or unimportant. To the contrary, the separation of powers principle at the heart of Klein is an important demarcation of responsibility between the political branches and the judiciary—leaving to the courts the ability to “say what the law is” even when Congress has effectively foreordained the outcome.

III. Klein and the MVP Dispute

That brings us back to the Mountain Valley Pipeline case. The current dispute centers on section 324 of the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 (a.k.a., the debt ceiling bill). That section provides a bunch of statutory approvals and ratifications of relevant decisions of federal agencies, and directs the Secretary of the Army to issue, within 21 days of the act’s enactment, those permits or verifications necessary for work on the pipeline to continue. Only section 324(e) speaks to the courts, and here’s what it says:

(1) Notwithstanding any other provision of law, no court shall have jurisdiction to review any action taken by the Secretary of the Army, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the Secretary of Agriculture, the Secretary of the Interior, or a State administrative agency acting pursuant to Federal law that grants an authorization, permit, verification, biological opinion, incidental take statement, or any other approval necessary for the construction and initial operation at full capacity of the Mountain Valley Pipeline, including the issuance of any authorization, permit, extension, verification, biological opinion, incidental take statement, or other approval described in subsection (c) or (d) of this section for the Mountain Valley Pipeline, whether issued prior to, on, or subsequent to the date of enactment of this section, and including any lawsuit pending in a court as of the date of enactment of this section.

(2) The United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit shall have original and exclusive jurisdiction over any claim alleging the invalidity of this section or that an action is beyond the scope of authority conferred by this section.

Note two things right off the bat: First, there is no command to the courts, unlike in the statutes at issue in Klein and Patchak, re: how they are supposed to rule on cases covered by this language. Subsection (e)(1) is a classic jurisdiction-stripping provision; subsection (e)(2) is a classic exclusive jurisdiction provision. Thus, unless Klein stands for a lot more than even a pro-Klein scholar like I think that it does, section (e)(1) is perfectly constitutional. Although there is endless debate over whether and when the Constitution limits Congress’s power to take jurisdiction away from the federal courts, the overwhelming consensus is that Congress can take jurisdiction away in statutory disputes—such as those relating to permitting and authorizations for construction of the pipeline.

Second, even if that’s incorrect, subsection (e)(2) funnels constitutional challenges to subsection (e)(1) into the D.C. Circuit—a not-so-subtle move by Senator Manchin (whose home state of West Virginia is in the Fourth Circuit) to move the case elsewhere. But there’s no viable constitutional objection, whether under Klein or any other case of which I’m aware, to Congress giving a specific federal court exclusive jurisdiction over a specific set of challenges; indeed, it does so all the time.

It may not be good policy for Congress to do so in a context like this one, where it’s for transparently political reasons, but that’s another matter. And if section (e)(2) is constitutional in directing even Klein claims into the D.C. Circuit, then the Fourth Circuit lacks jurisdiction even if section (e)(1) violates Klein. On that reading, the Fourth Circuit lacked the statutory authority to enter the stays at issue in the Mountain Valley Pipeline case whether or not section 324(e)(1) violates Klein.

To be clear, that’s no guarantee that the Supreme Court will vacate those stays later this week. A likelihood of success on the merits is one factor in the granting of emergency relief in a case like this, but there are other factors (including a showing of irreparable harm without the Court’s intervention). But it suggests that the Fourth Circuit erred even in a world in which section 324 does raise a serious Klein problem—and especially in one in which, as I’ve suggested above, it doesn’t.

I still think Klein matters quite a lot—especially because there’s a meaningful distinction between Congress creating one-sided procedural or substantive rules, on the one hand, and Congress purporting to apply those rules, on the other. Indeed, there are lots of hypothetical statutes Congress could pass to mess with the courts against which Klein is the best constitutional bulwark (e.g., “no court of the United States may consult foreign or international sources in interpreting the Constitution.”). But given the specific language of section 324, it’s hard to see the Mountain Valley Pipeline dispute as a meaningful test case for Klein going forward. And that may be the only thing that’s clear about the 1872 decision’s applicability today.

SCOTUS Trivia: A Redux on Pre-1883 Supreme Court Decision Dates

Readers with good memories may recall the earlier issue, from March 6, in which the trivia focused on the problems inherent in relying upon Lexis or Westlaw (or even the U.S. Reports) for dates of pre-1883 decisions. I raise it again here because Klein is another commonly seen example of the problem.

The official-ish reporter includes “Dec. 1871” in the inside margin of right-facing (“recto”) pages, a date that you’ll also see if you pull the case up in commercial databases. But that’s just the Term (i.e., the December 1871 Term). As the exhaustively thorough list maintained by the Supreme Court tells us, Klein’s an 1872 decision. Bluebookers, beware.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning at 8 ET.

Happy Monday, everyone. I hope that you have a great week!!

Justices Miller and Bradley, though nominally dissenting, agreed that the proviso was unconstitutional. They disagreed only with the majority’s conclusion that the Captured and Abandoned Property Act applied in the first place.

Might you comment on the Fourth Circuit opinions dismissing now that they are issued? Seems to me that (a) they may be giving boost unwittingly to the Supreme Court’s “you can’t touch me” attitude....whereas it seems that excessive involvement by congress with the courts is not really the issue and (b) the suggestion that this is the beginning of a constant trend seems contrary to the more frequent difficulty with with congress acting at all and this took weird stars to align to get this law passed.

Another clear explanation of a complicated issue. Thanks Steve for highlighting this Pipeline case.