3. The Tenth Justice

This week's issue introduces the unique (and, in recent years, increasingly contested) role of the "SG" — the Solicitor General of the United States

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us. Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s work or its key players; and some Court-related trivia.

In addition to Monday’s free newsletter, each Thursday will feature bonus content for paid subscribers (last week’s was a Thanksgiving-themed reflection on growing up in a family of lawyers). I hope you’ll continue to send feedback on what you like (and don’t like) about the newsletter, along with requests for topics to cover in future issues. And if you’re not already a subscriber, or are thinking about upgrading to a paid subscription (starting this week, the bonus content will be available only to paid subscribers), there’s no time like the present:

On the Docket

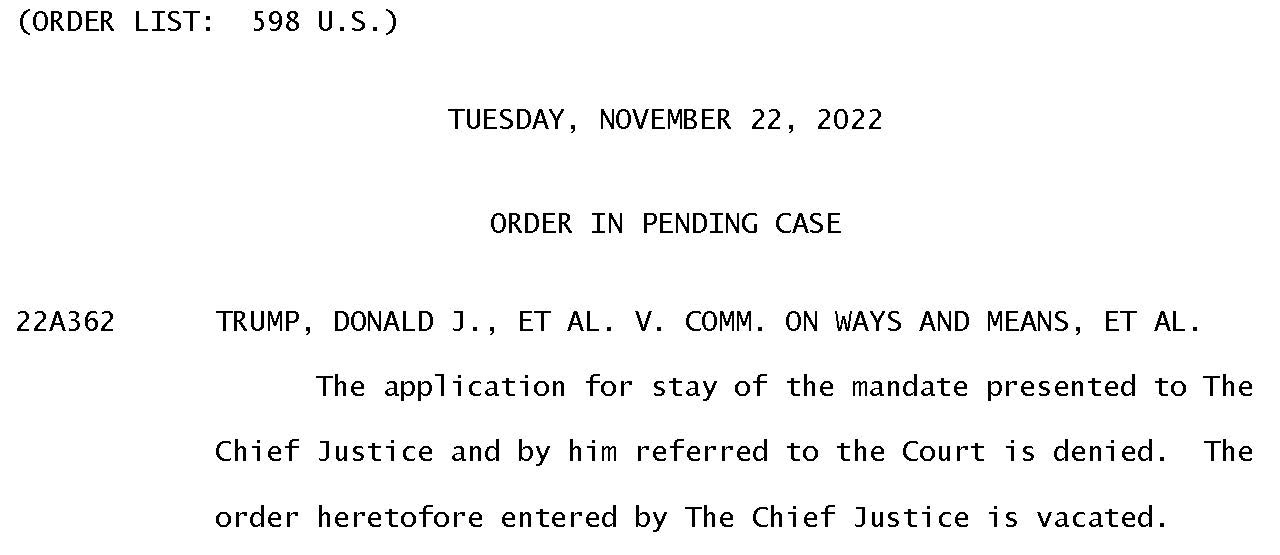

As is often the norm, Thanksgiving week was relatively quiet at the Court. In addition to Monday’s regular orders (and a grant of certiorari in a … dog poop-themed … trademark dispute), the two big rulings were Tuesday’s denial of former President Trump’s effort to block the House Ways and Means Committee from obtaining his tax returns; and Wednesday’s denial of a stay of execution to a Missouri prisoner whose execution is scheduled for later this week. Both orders were, as last week’s post introduced, unsigned and unexplained; and neither came with any public dissents.

The Justices are back on the bench this morning, with a regular Order List expected at 9:30 ET, and then the beginning of the “December” argument session, including Tuesday’s argument in United States v. Texas—a massively important case that’s ostensibly about the federal government’s ability to set immigration enforcement priorities, but is about a lot more than that (I’m planning to cover it in more depth in next week’s newsletter).

We could also hear from the Court as early as today, and likely sometime this week, about how it wants to handle the Biden Administration’s emergency application to unblock the student loan debt relief program, which is currently frozen by two separate “nationwide injunctions,” one from the Eighth Circuit and one from a federal district judge in Fort Worth, Texas. The Biden Administration has asked the Justices to vacate the Eighth Circuit’s injunction (and has a stay application pending in the Fifth Circuit to freeze the Fort Worth injunction), but, in the alternative, it has suggested that the Justices take up the merits of the student loan debt relief program on an expedited basis, with oral argument as early as February. One way or the other, it’s a good bet that we’ll know more by Friday…

The One First Long Read: The Solicitor General

The “Hearing List” for the Court’s December argument session tells a remarkable story: Nine cases are being argued. And in all nine, the federal government is appearing either as a party or as an amicus curiae (“friend of the Court”). This is only a bit of an aberration; during the October argument session, the federal government appeared in six of the eight arguments (four as an amicus); and it appeared in nine of the ten arguments the Court held during its November session (four as an amicus). In other words, of the 27 current-Term arguments that the Court will have held by the end of next week, the federal government will have participated in 24 of them.

And when the federal government appears in the Supreme Court, it is (almost) always represented by an officer sometimes known as the “Tenth Justice”: The Solicitor General of the United States.

The Origins of the Office of the Solicitor General

When Congress created the federal court system in the Judiciary Act of 1789, it buried the position of attorney general in the last sentence of the last section of the statute, almost as an afterthought. The attorney general was given exactly two duties: representing the United States before the Supreme Court, and providing legal opinions when asked for advice by either the president or other government actors.

The First Congress’s brief reference to the attorney general was also deliberately vague about where in the government that officer would sit. Weeks earlier, when the legislature had created the “great departments” of Foreign Affairs (now State), the Treasury, and War (now Defense), it was clear that these were executive departments, and that their heads — “secretaries” — were to be appointed by, and directly answerable to, the president. In contrast, the 1789 Judiciary Act said nothing at all about establishing a legal department. And it provided only that an attorney general “shall also be appointed,” without bothering to specify by whom!

The passive voice was deliberate. The judiciary bill that had initially passed the Senate earlier that summer would have given the power to choose the attorney general to the Supreme Court — reflecting the drafters’ view that the officer’s principal responsibility was to the justices, not the president. The House decided to muddle the language, with some members suggesting (with their implicit approval) that the ambiguity would allow President George Washington to name an attorney general himself. Washington did so, nominating Edmund Randolph just two days after signing the bill into law.

Still, it was hardly self-evident that the attorney general should — or would — be wholly subordinate to the chief executive. Most states at the Founding decided to have their attorneys general chosen and supervised by others. To this day, the attorneys general of 45 states are independent of the chief executive: Tennessee’s is appointed by its supreme court; Maine’s is appointed by the state legislature; and 43 are directly elected by the people. Only five states follow the federal model in which the attorney general is subordinate to the chief executive.

The 1789 statute’s ambiguity about the location of the attorney general’s office was also a reflection of Congress’ deep ambivalence about the office’s purpose. Was the attorney general a political advisor to the president? Was he an officer of the Supreme Court? Was he the chief legal adviser to the entire government, with duties and obligations to the courts and Congress that were independent of his relationship with his effective (if not formal) boss? At least initially, no one paid much attention to this debate. As legal historian Susan Low Bloch has explained, “the First Congress did not expect this part-time attorney, with no staff and little power, to play a major role in the emerging federal government.” (The actual enforcement of federal law was left either to private parties or to the local U.S. Attorneys, who were not, at least originally, in any way subordinate to the Attorney General.)

Obviously, that understanding has changed dramatically over the years — especially as the federal government’s regulatory power and its authority to safeguard individual rights expanded after the Civil War. Those developments helped to precipitate the belated creation of the Justice Department in 1870 — and the emergence of the department in the 20th century as a font of increasing power and increasing responsibility. But in the same statute in which Congress created the Department of Justice, it also created a new office, Solicitor General of the United States, to carry out at least one of the Attorney General’s original two responsibilities: To represent the United States in the Supreme Court.

The Solicitor General’s Independence

From that day onward, the Solicitor General (or “SG”) has typically been one of the nation’s top appellate lawyers. Of the 46 men and two women to hold the position as of today, five (including William Howard Taft, Thurgood Marshall, and Elena Kagan) have gone on to serve on the Supreme Court; and many more went on to stellar judicial careers in the lower federal courts. The Office of the Solicitor General has been referred to as “the finest law firm in the nation”; even junior positions are viewed as stepping-stones to the most prestigious private law practices or academic positions in the country.

Part of that reputation stems from the quality of the work that typically comes out of the office. But part of it reflects a deeper ethos. “There is a widely held, and I believe substantially accurate, impression,” wrote Rex Lee, Solicitor General from 1981 to 1985, “that the Solicitor General’s Office provides the Court from one administration to another . . . with advocacy which is more objective, more dispassionate, more competent, and more respectful of the Court as an institution than it gets from any other lawyer or group of lawyers.” Its lawyers even dress differently; male lawyers in the Solicitor General’s office are the only advocates who are still expected to appear before the Court in formal “morning” dress.1

In other words, the influence of the Solicitor General has derived, to a large degree, from its perceived independence — from the belief that it represents the interests of the United States as a whole, and not just the current policy preferences of the incumbent President. As Simon Sobeloff, Solicitor General from 1954 to 1956, explained, “the Solicitor General is not a neutral, he is an advocate; but an advocate for a client whose business is not merely to prevail in the instant case. My client’s chief business is not to achieve victory, but to establish justice.” (Sobeloff famously refused to sign the government’s brief or argue on the government’s behalf in one case in which he thought that principle had been neglected.) Frederick Lehmann, Solicitor General under President Taft, was even more blunt, remarking that “the United States wins its point whenever justice is done its citizens in the courts.” Or as Francis Biddle, one of President Roosevelt’s six Solicitors General, put it, “the Solicitor General has no master to serve except his country.” (A bunch of these quotes are collected in then-Solicitor General Seth Waxman’s really fascinating 1998 speech recounting the history of the office.)

Reinforcing that independence, the Solicitor General is the only federal officer other than the Vice President with formal offices in multiple branches of the federal government, one in the main building of the Department of Justice and one in the Supreme Court, reinforcing the unique role that the Solicitor General is supposed to play in serving two masters. The Solicitor General does not just have a physical presence at the Supreme Court; the Court’s rules and traditions both formally and informally privilege the Solicitor General as the de facto leader of the Supreme Court’s bar — the unofficial representative of all lawyers who appear before the Justices. Thus, although Solicitors General have developed a “special relationship” with the Court, in the words of former Solicitor General Seth Waxman, that relationship “is not one of privilege, but of duty — to respect and honor the principle of stare decisis, to exercise restraint in invoking the Court’s jurisdiction, and to be absolutely scrupulous in every representation made.”

The Solicitor General, Today

For better or worse, recent years have seen charges from both sides of the spectrum that the Solicitor General has become increasingly political, if not partisan — and that, too often, the holder of that office has prioritized short-term victories for the incumbent administration over long-term victories for the broader principles (and clients) it purportedly serves. Indeed, there’s quite a robust academic literature on the subject of whether successive SGs have become increasingly partisan. I do think SGs of both parties have pushed the envelope relative to their predecessors (especially the Trump Administration’s use and abuse of the shadow docket), but one of the interesting data points is that the Justices have not objected, at least publicly.

For instance, the Solicitor General is still far more successful than any other party in persuading the Justices to grant certiorari. The SG is still allowed to participate as amicus almost anytime it wants (indeed, it’s news when the Court refuses to allow the SG to so participate, as it’s done exactly once in the last two Terms). And so the result is that the SG is still the most important lawyer, by far, before the Court. Again, the fact that someone from the SG’s Office is arguing each of the nine cases the Court is hearing over the next two weeks is powerful evidence of this phenomenon. (In the Vanderbilt Law Review, Darcy Covert and Annie Wang offer both comprehensive historical data and a normative critique of the frequency with which the Court allows the SG to participate as an amicus.)

Finally, the Court often even leans on the SG in deciding whether to take up especially controversial (or complicated) disputes to which the federal government is not a party. So far this calendar year, the Court has issued 23 “calls for the views of the Solicitor General” (CVSGs), not-very-optional invitations to the government to weigh in on whether certiorari should be granted in disputes to which the federal government is not a party. (For an example of a CVSG brief, here’s one filed last Monday.) The Justices don’t always follow the SG’s “grant” or “deny” recommendations, but they follow them more often than they don’t. (N.B.: The longest currently outstanding CVSG is in a case in which I represent the respondents.)

Thus, the Office of the Solicitor General plays an outsized role both in helping the Justices set their agenda and in appearing before the Court far more often than any other lawyers. There’s lots more to say about the merits and demerits of the SG’s current role and relationship to the Court, but no one can deny the unique role that the SG has played, and continues to play, in the work of the nine titular Justices.

SCOTUS Trivia: The Tenth Seat

The Solicitor General may often be referred to as the “Tenth Justice,” but there were two brief periods in the Court’s history in which there really were ten Justices: from May 20, 1863 to October 12, 1864; and from December 15, 1864 to May 30, 1865. Nor was it a mix-up of some kind; it was entirely by design.

When Congress first established the Supreme Court in the Judiciary Act of 1789, it created six seats — the Chief Justice and five Associate Justices. The idea was that two of the Justices would each represent one of the three new circuit courts. Starting in 1802 (when Congress reorganized the circuits into six courts of appeals), Congress started matching the size of the Court to the number of circuits on a 1:1 basis. Thus, a seventh seat was added upon the creation of the Seventh Circuit in 1807; and eighth and ninth seats were added upon the creation of the Eighth and Ninth Circuits in 1837. When Congress created a new Tenth Circuit in 1863 to encompass California, it likewise created a tenth seat (which President Lincoln promptly filled with Justice Stephen Field, whose attempted assassination, and the litigation it precipitated, featured prominently in the bonus content from November 17).

Field joined the Court on May 20, 1863. From then until Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney’s death on October 12, 1864, there were ten commissioned Justices (Taney, Wayne, Catron, Nelson, Grier, Clifford, Swayne, Miller, Davis, and Field), although it’s not clear, given various illnesses and other absences, whether all ten participated together at any point during the Court’s December 1863 Term. And from the swearing in of Salmon Chase as Chief Justice on December 15, 1864, until the death of Justice John Catron on May 30, 1865 (so, most of the Court’s December 1864 Term), the Court also appears to have had ten Justices at the same time.

To prevent President Andrew Johnson from filling any vacancies on the Court, Congress passed the Judicial Circuits Act on July 23, 1866. That Act provided that there would be only six associate justices, and that each seat in excess of that total would be eliminated when it became vacant. Thus, the Act extinguished Catron’s (vacant) seat the day it was passed (dooming Johnson’s pending nomination of Henry Stanbery to fill that seat); and it extinguished the seat held by Justice Wayne upon his July 5, 1867 passing, leaving the Court with eight seats. It also broke what had been a 77-year practice of tying the size of the Court to the number of circuits, 2:1 at first, and then 1:1 since 1802.

But the Court never fell back to seven seats; before another vacancy occurred, Ulysses S. Grant had succeeded Johnson as President, and Congress, in the Judiciary Act of 1869, restored the Court to nine seats — where it’s remained (not without some controversy) ever since.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. If you liked it, I hope you’ll consider sharing it with your friends (or, even better, your frenemies):

And if you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content, including monthly AMAs; sneak peeks (including excerpts from my forthcoming book on the shadow docket); and other surprises, please consider becoming one. This week’s bonus issue, which will be available only to paid subscribers, will include my Top 5 favorite law (and law-related) books of the year, several of which are about the Supreme Court (and may make for good holiday reading):

Happy Monday, everyone! Have a great week!

When she became the first woman to serve as Solicitor General in 2009, Elena Kagan (who thought that the woman’s version of a morning coat looked “ridiculous”) is said to have received the Justices’ approval, through intermediaries, to argue in a business suit.