27. Why I Wrote (and Hope You'll Read) a Book About the "Shadow Docket"

With publication day coming tomorrow, a personal reflection on trying to make the more technical side of the Court's history, output, and impact more accessible to lawyers and non-lawyers alike

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it with your networks (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

We’re into that part of the Court’s calendar that’s dominated by rulings in argued cases (the “merits docket”). There were no orders out of the Court last week, but the Court handed down five decisions in argued cases on Thursday, in the following order:1

Santos-Zacaria v. Garland: For what was basically a unanimous Court (Justice Alito concurred in the judgment, in an opinion joined by Justice Thomas), Justice Jackson held that an exhaustion requirement for certain claims by non-citizens facing removal is not “jurisdictional,” meaning that courts have at least some ability to consider those claims even if they were not presented to immigration officers.

National Pork Producers Council v. Ross: In what was easily the most significant of Thursday’s rulings, an unusual 5-4 majority (with Justices Thomas, Sotomayor, Kagan, and Barrett joining the key parts of Justice Gorsuch’s majority/plurality opinion) upheld a California animal cruelty law that requires pork sold in the state to be produced under humane conditions even if the production occurs out of state. The case was pitched as a major federalism dispute, since California’s sheer size means that out-of-state businesses will feel especially compelled to comply with its rules (versus taking the hit from the lost business if they didn’t). But the majority held that the California law did not violate the “Dormant Commerce Clause,” which could have a big impact on both California’s and other large states’ efforts to regulate other out-of-state conduct by making compliance with an array of public policy preferences a condition of doing business in the state.

Financial Oversight & Management Board for Puerto Rico v. Centro de Periodismo Investigativo: For an 8-1 Court (with Justice Thomas dissenting), Justice Kagan held that Congress must speak clearly before it abrogates Puerto Rico’s sovereign immunity, and that the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act of 2016 (PROMESA) did not include such an express overriding of immunity. Thus, the Financial Oversight & Management Board established by the Act can’t be sued without its consent. Justice Thomas’s dissent argues that, as a federal territory, Puerto Rico doesn’t have sovereign immunity in the first place—so there was nothing for Congress to abrogate.

Percoco v. United States: The last two rulings both involved unanimous majorities paring back federal public corruption laws, part of a broader pattern in which the Court has been hostile to aggressive interpretations of those statutes by federal prosecutors. In the first case, Percoco, Justice Alito wrote for seven Justices (Justice Gorsuch concurred in the judgment in an opinion joined by Justice Thomas) to hold that prosecutions for “honest services fraud” require more than just a showing that a private person’s influence over government officials exceeds some ill-defined threshold (versus an objective measure of how the dishonest services affected governmental decisionmaking). The Court didn’t articulate what the showing must be, but rather left it to the lower courts in this case (and others) to articulate clearer standards.

Ciminelli v. United States: Finally, Justice Thomas wrote for a unanimous Court in Ciminelli, holding that federal fraud statutes do not authorize prosecutions based on the “right to control” theory—that individuals have a property interest in valuable economic information needed to make discretionary economic decisions, so that depriving individuals of such information in order to alter their decisionmaking can be fraud. Because such a right was not understood to create a property interest at common law, the Court held that it could not be read into the federal fraud statutes without clearer indication that Congress intended the statutes to be so read.

Even with five decisions last Thursday, there are still 40 cases to go in which the Court held arguments earlier this Term, with the next chance for merits rulings coming this Thursday at 10 ET. In the interim, we expect a regular Order List out of last Thursday’s Conference this morning at 9:30 ET. And we also expect the justices to rule soon on a pending emergency application seeking to block bans on assault weapons that Illinois and the City of Naperville enacted after the Highland Park shooting last year. Briefing was complete last Wednesday, which seems to suggest that at least someone is writing an opinion respecting the Court’s forthcoming disposition.

The One First Long Read: Me on the Shadow Docket

At first blush, it might seem like a fool’s errand strange enterprise to try to write a book for a popular audience about the more technical, esoteric side of the Supreme Court’s docket. And I also usually save these more personal posts for Thursday’s bonus content. But given tomorrow’s publication date, I thought I’d take advantage of the opportunity to reflect a bit on where the book came from and what I’m hoping to accomplish by writing/publishing it.

Why a Book on the Shadow Docket?

When I started tracking the Supreme Court’s handling of emergency applications in the fall of 2017, I certainly didn’t think it would eventually turn into a book. Rather, as it seemed like the justices were both receiving and granting an unusual number of emergency applications, I thought it would be useful to create an informational resource for those who cover, write about, or otherwise follow the Court. As time went on, though, and the Court … kept doing novel things on the shadow docket, it seemed more and more worth it to attempt a more holistic study of what the justices were up to.

The first iteration (published in the Harvard Law Review in 2019) looked at a very specific subset—emergency applications by the federal government, and just how radical the differences were in how the Trump administration was using (and succeeding on) them compared to its predecessors. But the more I worked on that piece, the more it seemed like a bigger project was lurking, one that (1) didn’t just look at such a small subset of cases; and (2) tried to put the current Court’s behavior into more of a historical context.

Just as importantly, the more I wrote publicly about what was happening on the shadow docket (whether on Twitter, through op-eds, or elsewhere), the more it seemed to me that the public, and not just the legal academy, was the right audience for such a project. Yes, writing for a general audience about the more technical and procedural sides of the law can be … a challenge. And persuading trade presses to publish such a book is … even more so. But writing a technical book for a technical audience wouldn’t accomplish my broader goal, which was to raise public awareness of how much significant stuff happens in the Court’s literal and metaphorical shadows. We’re not going to do that unless we’re speaking to the public.

Hence, the two main goals of the book: To provide readers with a comprehensive historical and contemporary introduction to how the Supreme Court handles all of the cases that come before it; and to unpack my argument for why the current Court’s behavior differs from its predecessors in ways that ought to seriously trouble even those whose ideological preferences align more closely with the current majority’s than mine. The first part of this story (which the book unpacks in Chapters 1, 2, and 3) helps to explain how a Court that was supposed to be the “least dangerous branch,” as Hamilton wrote in Federalist 78, has come, over its history, to play such a central and dominant role, for better or worse, in so many contemporary social and public policy disputes. (The main figure in this narrative turns out to be Chief Justice William Howard Taft—and his outsized role in pushing for and establishing the Court’s institutional autonomy as a means of consolidating its power.)

The second part of the book pivots to more recent events, including the Trump administration (Chapter 4); COVID (Chapter 5); the 2020 and 2022 election cycles (Chapter 6); and the SB8 case and its aftermath (Chapter 7). It’s this part of the book that will likely divide readers far more than the first part, but I’ve done my best to lay out the evidence for the biggest claims the book advances—that the conservative majority, often without Chief Justice Roberts, came to use the shadow docket first as a way of making policy without making law, and, by late 2020 and 2021, as a way of changing the law on the books, and not just on the ground, in lieu of the merits docket. The subtitle of the book (“How the Supreme Court Uses Stealth Rulings to Amass Power and Undermine the Republic”) is certainly provocative; I do my best, especially in Chapters 5 and 6, to demonstrate that it’s not hyperbolic. At the very least, the book pushes readers to consider whether, even if there are more principled explanations for the justices’ behavior, their failure to provide those explanations has enabled the critiques offered in the book and elsewhere.

The book closes by arguing that the Court’s recent behavior on the shadow docket is a symptom of a broader disease—one in which Congress has stopped exerting any pressure on the Court or its docket, leaving the justices to their own devices with regard to which cases they are deciding, in which contexts, and through which vehicles. Thus, although there are a battery of specific reforms that the Court and Congress can (and should) pursue, the real bottom-line is to make the case for increased checks on the Court, whether from public pressure (now that we all know more about what the Court has been up to), from Congress, or both. In that respect, simply making it through the book accomplishes one of my main goals; whether folks agree with all of it or not, I have to hope that everyone will understand the Court a little better by the end, even folks who already understand it quite well.

Why Do I Hope You Will Read It?

If you’re already subscribed to this newsletter, you probably don’t need to be persuaded as to why all of this might be worth reading. Indeed, I hope at least some of you will think of the newsletter as akin to a free preview of the book; some of the stories overlap, and a bunch of the broader themes surely do.

But there are arguments and motifs that I can unpack in a 100,000-word book a lot more coherently than in a series of periodic 2500-word newsletters. There’s history I can trace and document in a lot more detail; anecdotes into which I can inject a lot more color (like the one that forms this week’s trivia, below); and, frankly, a higher quality to the writing—since, unlike this gobbledygook, someone else (multiple someone else’s, actually) edited it. Plus, whereas the newsletter is largely reactive to current events (see three recent issues each of which touched directly or indirectly on ethics), the book stands alone as covering a period that ended (at the end of the October 2021 Term on October 2, 2022). So if you’ve been enjoying these weekly missives, I hope you’ll consider tracking down the book, too.

Where You Can Find It / Me

To that end, I thought I’d flag both where you can find the book and where you can find me talking about the book (and with whom).

With regard to the book, it should be available from just about all of your favorite booksellers for pre-order (and, as of tomorrow, out in the wild). If you buy it today (Monday, May 15), you can still take advantage of two incentives that the publisher, Basic Books, is offering for pre-orders:

Those who pre-order directly from Basic Books can take 20% off the list price by using the code “VLADECK20.” Note that this code expires at 11:59 EDT tonight.

A pre-order receipt from any vendor can be used to unlock a really fun 30-minute video conversation between me and Dahlia Lithwick about the book and the Court. You can submit a copy of your receipt here, but note that the receipt has to be dated May 15 or earlier (and the submission system will only be live for a few more days).

If you’d rather wait for the reviews to come in, no worries! But we’re also hosting a series of in-person and remote events to talk about the book.

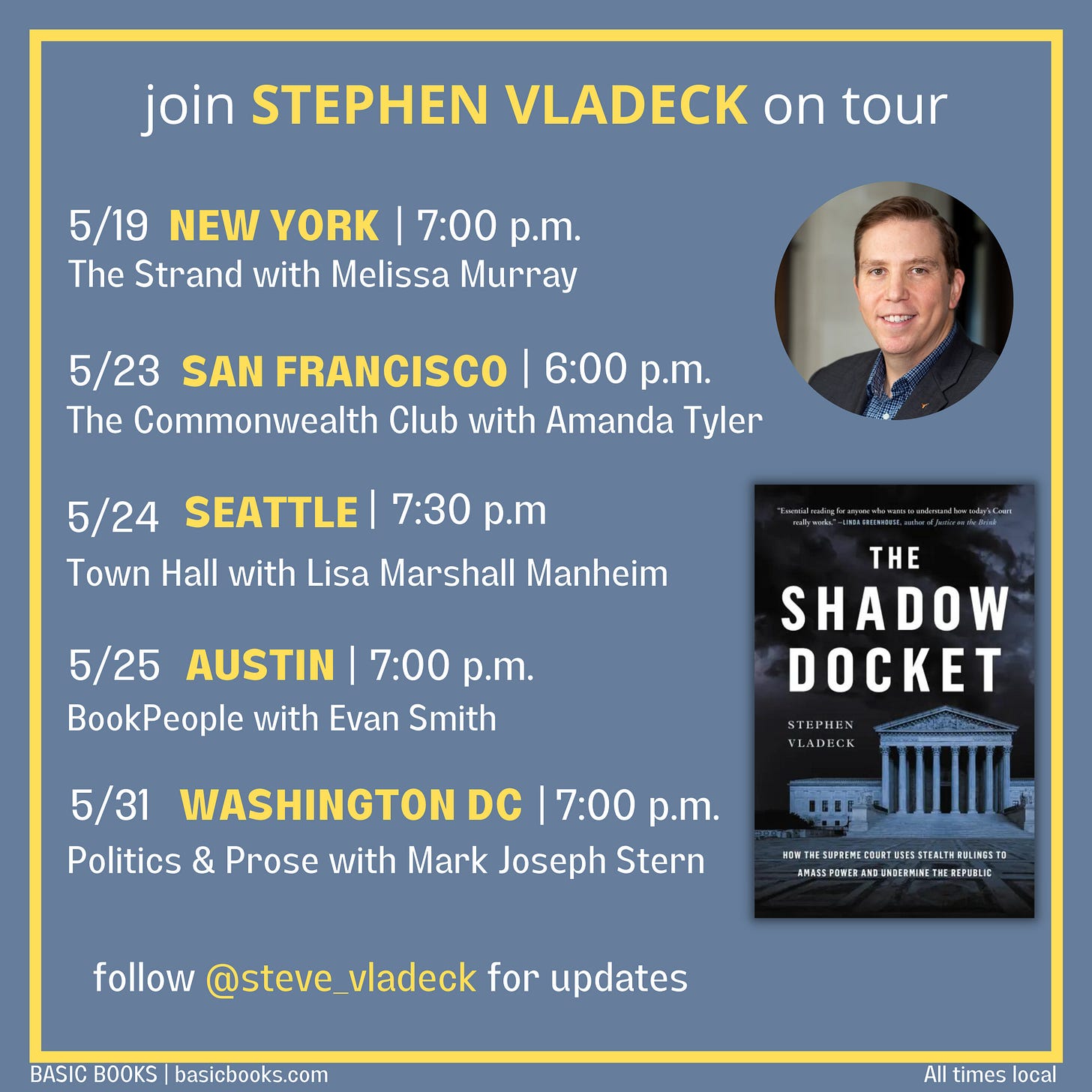

In-Person:

New York (Friday, 5/19): The Strand with Prof. Melissa Murray, 7:00 p.m. ET

San Francisco (Tuesday, 5/23): The Commonwealth Club with Prof. Amanda Tyler, 6:00 p.m. PT

Seattle (Wednesday, 5/24): Town Hall with Prof. Lisa Manheim, 7:30 p.m. PT

Austin (Thursday, 5/25): BookPeople with Evan Smith, 7:00 CT

D.C. (Wednesday, 5/31): Politics & Prose (Conn. Ave. Store) with Mark Joseph Stern, 7:00 ET

Remote:

National Constitution Center Town Hall (Monday, 5/22): 12:00 ET (with Adam Liptak and Prof. Jenn Mascott)

Harvard Bookstore (Tuesday, 5/30): 6:00 ET (with Jack Goldsmith)

Needless to say, I’d love to see you either in person or online if your schedule permits.

SCOTUS Trivia: LBJ and the Shadow Docket

One of the central ways that the book tries to make the more technical parts of the Supreme Court’s docket both accessible and interesting is by using colorful stories/anecdotes to illustrate the themes of each chapter. The chapter about elections starts with perhaps my favorite one, about Lyndon Baines Johnson.

To skip right to the punchline, in 1966, then-President Johnson hosted an 80th birthday party at the White House for Justice Hugo Black. Johnson toasted Black at the party by noting that, “if it weren’t for Mr. Justice Black at one time, we might well be having this party. But one thing I know for sure, we wouldn’t be having it here.”

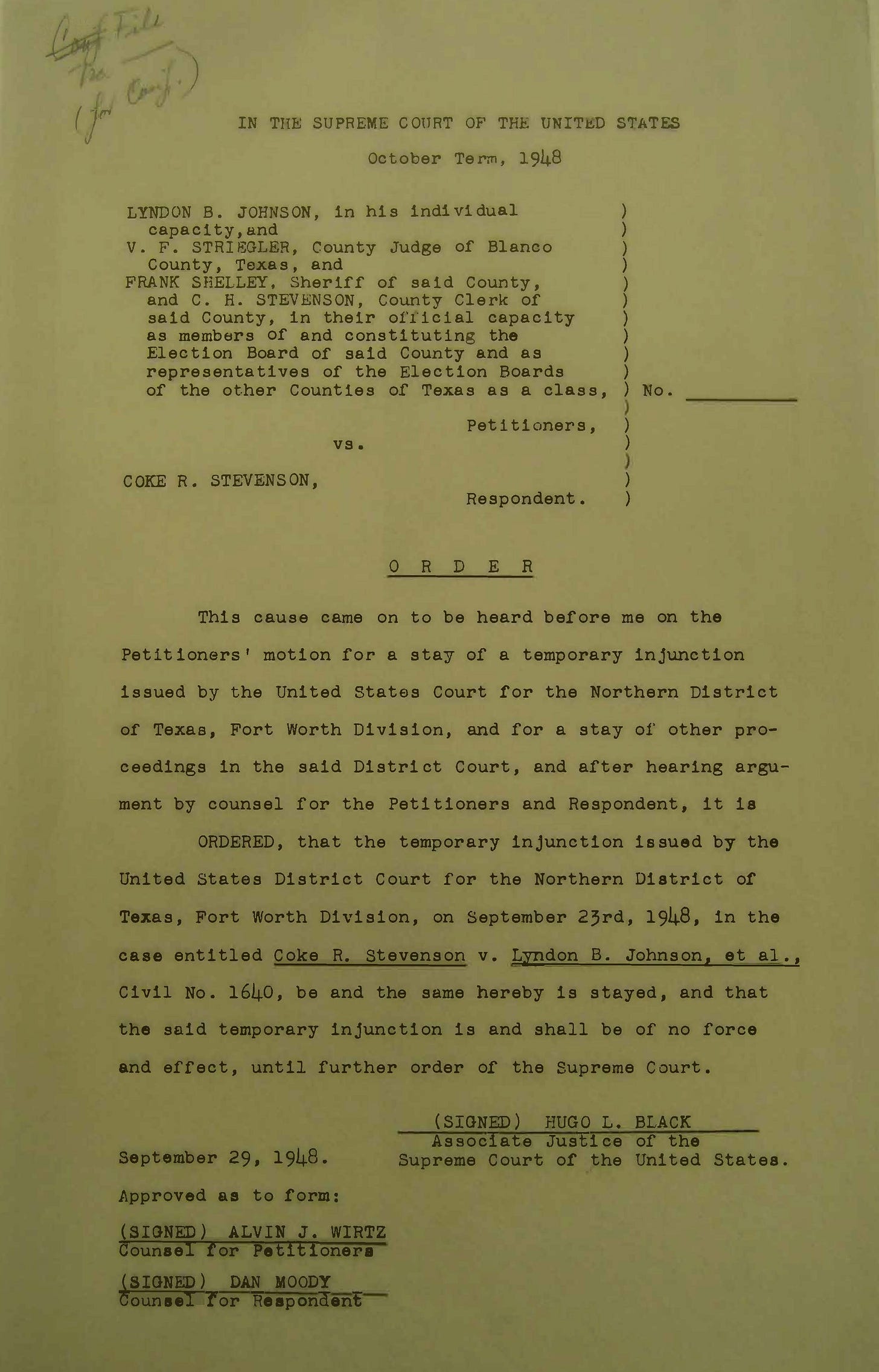

Johnson’s cryptic allusion was to Black’s role in the 1948 Texas Democratic Senate primary, and how the in-chambers order pictured below (with a big shout-out to Professor John Barrett for posting this copy of it) saved LBJ’s career.

There’s a lot more to the story of how LBJ … “won” … that primary, including the significant role played by future Justice Abe Fortas. But I’ll save that for the book.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning at 8 ET.

Happy Monday, everyone! I hope you have a great week.

The Court’s website lists the five decisions from last Thursday in the opposite order—because it follows the Court’s order of seniority. But decisions are handed down in reverse order of seniority, which is the order I’m following here.

Mine should be delivered today. Looking forward to reading it. At this stage I am focused on calling out the illegitimacy and corruption of this “court”. I do not think it’s power is compatible with a truly Democratic country. And, reading history, perhaps it was designed that way. It’s always been an un-Democratic institution that, with few exceptions, has existed to protect the wealthy and powerful to the exclusion of everything else.

I look forward to your book. However, it seems to me that SCOTUS is not so much seeking to enhance its powers as it is responding to external forces. Most notably, Congress has abdicated its legislative responsibilities over recent decades leading to overly aggressive action by the executive branch. Both of these factors have forced the Court to take on an outsized role in addressing major issues that should be left to the political branches. Another is the proliferation of nationwide injunctions by lower courts in recent years, which often force early intervention by the Supreme Court. Maybe your book will prove me wrong.