24. Justice Alito and the Shadow Docket

A detailed look at Justice Alito's eye-opening dissent from the Court's Friday night stay in the mifepristone case.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it with your networks (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

Obviously, the biggest headline out of the Court last week came shortly after 6:30 p.m. ET on Friday, when the Justices issued a full stay of Judge Kacsmaryk’s mifepristone ruling pending appeal. The unsigned, unexplained order offered no rationale for the Court’s action, but it froze Kacsmaryk’s order:

pending disposition of the appeal in the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and disposition of a petition for a writ of certiorari, if such a writ is timely sought. Should certiorari be denied, this stay shall terminate automatically. In the event certiorari is granted, the stay shall terminate upon the sending down of the judgment of this Court.

In other words, Kacsmaryk’s ruling will go into effect only if (1) the Fifth Circuit affirms it; and (2) the Court either denies the resulting cert. petition or grants certiorari and ultimately affirms Kacsmaryk’s ruling itself. And critically, the stay remains in effect until (2) happens, so nothing that the Fifth Circuit does in the pending appeal will directly affect the status quo. The bottom line is that nothing is going to change with respect to legal access to or approval of mifepristone anytime soon. Justice Thomas publicly noted, but did not explain, his dissent; and Justice Alito wrote a … remarkable … four-page dissenting opinion, which is the subject of this week’s “Long Read,” below.

As has become increasingly common in recent years, the action on the Court’s emergency docket overshadowed <couldn’t resist> a busy week on the merits docket, including the second-to-last week of scheduled oral arguments for the October 2022 Term and four(!) signed decisions in argued cases (bringing the still-way-behind total for the Term up to 13). Briefly summarizing the latter:

In New York v. New Jersey, a unanimous Court held, in an opinion by Justice Kavanaugh, that New Jersey could unilaterally leave the interstate compact creating the Waterfront Commission of New York Harbor. For aficionados of the law of interstate compacts, this one’s for you.

In perhaps the most significant of the four rulings, Reed v. Goertz, a 6-3 Court sided with a Texas death-row inmate in a dispute over when the statute of limitations began to run on his federal court suit to obtain potentially exculpatory DNA testing of certain evidence that was used against him. Justice Kavanaugh’s majority opinion concluded that the two-year time limit for bringing his federal claim began to run when the state-court litigation ended, and not, as the Fifth Circuit had held, when the prisoner’s state-court claim had first been denied by a trial court. Justice Thomas and Justice Alito filed separate dissents on separate grounds (the latter of which was joined by Justice Gorsuch).

Justice Kavanaugh’s third majority opinion of the week came in Turkiye Halk Bankasi, S.A. v. United States, a case about whether a Turkish state-owned bank could be criminally prosecuted in the United States for conspiring to evade Iranian sanctions. The majority opinion held that the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act categorically does not apply to criminal prosecutions, and thus doesn’t preclude the prosecution of Halkbank. Instead, any immunity Halkbank could claim would have to come from common-law principles—which the majority left for the Second Circuit to consider on remand. Justice Gorsuch, joined by Justice Alito, concurred in the judgment in part and dissented in part; he would have held that the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act does apply to criminal prosecutions, but that Halkbank’s alleged conduct falls within one of its exceptions (for commercial activities)—so that the prosecution can proceed.

Finally, Justice Jackson wrote for a unanimous Court in MOAC Mall Holdings, LLC v. Transform Holdco LLC, concluding that a technical provision of the federal bankruptcy code is not “jurisdictional,” meaning that it can be waived or forfeited by the parties if it’s not invoked in a timely manner. (This is just the latest in what has become a cottage industry of Supreme Court rulings over the past two decades that have concluded that statutes aren’t jurisdictional unless they make pretty clear that they are.)

This week should be quieter. We expect a regular Order List at 9:30 ET today, and then the last week of the April 2023 argument session begins at 10:00. But no further rulings in argued cases are expected until Thursday, May 11. This is the point in the Term in which the Justices’ focus shifts from cases in front of them to cases behind them—and to finalizing and handing-down rulings in the cases that were already argued.

To that end, one interesting data point is which Justices still haven’t been heard from at all. The 13 signed decisions in argued cases so far this Term have come from six authors: Kavanaugh (4); Sotomayor, Gorsuch, Barrett, and Jackson (2 each); and Kagan (1). Those are the six junior-most Justices by seniority. Nothing yet from the Chief Justice, Justice Thomas, or Justice Alito—who likely received at least the original majority assignments in the lion’s share of the bigger and more divisive rulings that are coming.1 Make of that what you will. (Or, as my wife said upon hearing this, “buckle up.”)

The One First Long Read: Alito’s Mifepristone Dissent

As noted above, Justice Alito filed a four-page dissent from the Court’s unsigned, unexplained order Friday night staying Judge Kacsmaryk’s mifepristone ruling pending appeal. It’s an eye-opening opinion both in the charges it makes and the tone it strikes—and folks should read it for themselves. In a nutshell, the dissent makes three principal arguments:

That, by voting to grant a stay, at least some of the Justices in the majority engaged in the same shadow docket behavior that they had previously criticized;

That the federal government’s (putatively) inequitable behavior militated against granting a stay; and

That Danco Laboratories (one of mifepristone’s two U.S. sponsors) had also failed to show a sufficient risk of irreparable harm to justify a stay.

Each of these claims deserves its own attention, so I’ve broken them out into subparts, below.

Claim 1: Shadow Docket Hypocrisy

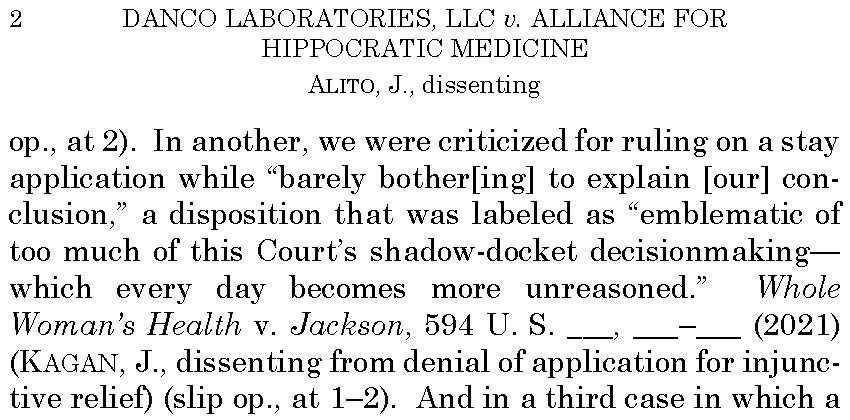

Let’s start with the hypocrisy charge. In leveling it, Alito quoted from an earlier dissent by Justice Sotomayor and from Justice Kagan’s dissents in the Alabama redistricting and SB8 cases, all of which criticized the majority’s use of the shadow docket. But Alito cut off his quote from Kagan’s SB8 dissent in a way that is quite revealing. In that case, Kagan had criticized the majority’s refusal to intervene to block Texas’s six-week abortion ban as “emblematic of too much of this Court’s shadow-docket decisionmaking—which every day becomes more unreasoned, inconsistent, and impossible to defend.” In his dissent on Friday, Alito cut off Kagan’s charge at “unreasoned,” as if that was her only objection:

After citing these prior opinions, Alito comes to his point: “I did not agree with these criticisms at the time, but if they were warranted in the cases in which they were made, they are emphatically true here.” In other words, Alito is accusing Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, and Barrett (whose cryptic October 2021 concurrence in Does 1–3 v. Mills he also invoked)2 of hypocrisy because the Court granted emergency relief without any explanation in the mifepristone case, and then using the charge of others’ hypocrisy to defend his own hypocrisy here (since he was on the other side in all four of the cases he cited).

The shameless whataboutism aside, what Alito’s charge misses is why critics of the shadow docket actually criticize it (truncating the Kagan quote didn’t help). The point is not, as Alito implies, that all emergency intervention by the Supreme Court is unwarranted. Every appellate court needs a mechanism for providing emergency relief, and just about everyone agrees that there will be at least some circumstances in which emergency relief is warranted. Perhaps that’s why there isn’t a single Justice who has consistently voted against emergency relief in all cases either recently or, near as I can tell, ever.

I can’t speak for others, but at least my criticisms of how the Court has abused the shadow docket has focused on features that go way beyond how often the Court has intervened in recent years. Here’s a passage from my testimony at a September 2021 Senate Judiciary Committee hearing:

In other words, shadow docket rulings aren’t problematic based on whether they do or do not grant emergency relief; they’re problematic because the Court’s unexplained rulings both appear to not be applying neutral procedural, substantive, and/or jurisdictional principles consistently and are nevertheless being treated as precedents by both the Justices themselves and lower courts. That is to say, granting emergency relief in some contexts in which the traditional (statutory) criteria clearly aren’t satisfied, and not explaining why, paints the Court in an especially unflattering light when the grants tend to correspond with the partisan valence of the dispute. (This is one of the themes of Chapters 4, 5, and 6 of my forthcoming book on the shadow docket.)

Yes, it would have been better if the Justices in the majority in Friday’s ruling had offered a modicum of explanation for why they voted to stay Judge Kacsmaryk’s ruling (especially if part of the reason is a lack of standing, which would doom the case on remand).3 But the Court is not acting abusively any time it grants emergency relief; the abuses come when it does so in ways that defy settled doctrinal, procedural, and jurisdictional constraints without even trying to explain why those constraints don’t apply. (One good case in point: Louisiana v. American Rivers, in which a 5-4 Court granted an unexplained stay despite no plausible argument that the applicants could demonstrate irreparable harm, as Justice Kagan pointed out in a dissent that Chief Justice Roberts joined.)

There’s no actual argument in Alito’s dissent (or in any of the public defenses of it that I’ve seen) that Friday’s ruling checks any of those boxes. (As we’ll get to below, this was actually an exceptionally easy case for a stay under the governing criteria.) Thus, unless it’s never appropriate for the Court to grant emergency relief without a full-throated explanation, Alito’s critique of the majority doing so here would ring more than a little hollow even if it came from someone without his track record on the subject.

To that end, consider some of Justice Alito’s recent writings on the shadow docket. Exactly 18 days ago, Alito dissented from the Court’s refusal to grant emergency relief in the West Virginia transgender sports case, writing that he would have granted relief notwithstanding the fact that West Virginia had sat on its hands rather than appeal a preliminary injunction for 18 months at an earlier stage of the litigation (a delay that necessarily doomed any claim of irreparable harm, and thus of meeting the standard for emergency relief). No matter, Justice Alito wrote; the Court should just “put aside” West Virginia’s dilatory behavior.

Or last fall, when Alito dissented from the Court’s refusal to stay a New York trial court injunction even though (1) as the majority made clear, further relief remained available in the New York state courts; and (2) there were serious questions as to whether the Supreme Court had appellate jurisdiction at that point in the case. Or last summer, when Alito dissented from the Court’s decision to put back on hold Texas’s controversial ban on content moderation by large social media companies, and complained about lower courts imposing de facto “preclearance” requirements by enjoining government policies. Or the myriad cases during the Trump administration in which Alito regularly voted in favor of unexplained stays of lower-court injunctions where the government’s only argument for irreparable harm was that one of its policies had been blocked. Neither Alito nor anyone else has yet to explain why that argument was good enough to (repeatedly) stay injunctions of Trump policies, but hasn’t justified similar intervention in favor of Biden policies (indeed, the next nationwide injunction of a Biden policy that Alito publicly votes to stay or reverse will be the first).

Other examples abound, but I suspect the point has been made.

Ultimately, Justice Alito is absolutely correct that the Court has behaved inconsistently and problematically in some of its recent shadow docket decisionmaking; that’s part of why I wrote the book, and I hope readers will check it out to see these arguments in more detail and decide whether they are persuaded. But it’s important to correctly identify what made those prior rulings both “inconsistent” and “impossible to defend,” to use the charges Justice Kagan leveled and Alito’s dissent omitted. And properly identified, those understandings not only support what the majority did on Friday, but they suggest that, if there is hypocrisy afoot, it’s coming from the author of the dissent.

Claim 2: The Biden Administration’s Unclean Hands

Alito then defends his vote against a stay by turning to whether the Biden administration had shown that irreparable harm would result from allowing Judge Kacsmaryk’s ruling to go into effect (tellingly, he does not suggest that the Biden administration is unlikely to succeed on the merits—even though that is supposed to be the most important equitable factor). Here, things really run off the rails.

First, he portrays the FDA’s irreparable harm argument as turning entirely on the “regulatory chaos” that would result from the seeming conflict between Kacsmaryk’s ruling and the contraindicated decision by a federal judge in Washington state in a different case (I summarized the two rulings in an earlier post). But that’s not a remotely fair summary of the FDA’s position; even without Judge Rice’s ruling, Judge Kacsmaryk’s order, especially as modified by the Fifth Circuit, would have produced massive effects (including a fair amount of chaos) entirely on its own—because there would have been substantial uncertainty about what to do with stockpiled mifepristone (and whether doctors or pharmacists could continue to dispense it in states in which it is otherwise unlawful); because it would have taken the generic mifepristone entirely off the market; because Danco could not have continued to distribute any mifepristone in interstate commerce without going through a re-labeling and re-approval process; and so on. Perhaps Alito doesn’t agree that that’s “regulatory chaos,” but virtually none of those effects would stem from any conflict, real or otherwise, with the ruling from Spokane.

In any event, Justice Alito’s argument is basically that the FDA doesn’t have clean hands because it (1) “did not appeal” Judge Rice’s ruling; and (2) opposed intervention in that case by seven (red) states. He doesn’t note that the FDA still has lots of time to appeal that ruling, or that it had already sought (and received) clarification from Judge Rice as to exactly what its obligations under it are—quite possibly in anticipation of appeal.

Nor does he note that the states that sought intervention were not doing so to appeal Judge Rice’s ruling (as his dissent certainly seems to imply), but rather to bring an entirely different challenge to the FDA's regulations from the one the plaintiffs were pursuing (indeed, the states had sought to intervene before Judge Rice issued his injunction). It’s one thing to accuse a party of unclean hands as a basis for denying equitable relief; it’s quite another to support that accusation with such a one-sided (and arguably misleading) portrayal of why the party’s hands are supposedly unclean. Either way, “unclean hands” usually requires more than just “the party didn’t appeal as quickly as it could have” and “it opposed an unrelated intervention attempt by non-parties.”

Claim 3: Prosecutorial Discretion and the Lack of Harm

Finally, Justice Alito comes to the other party seeking emergency relief—Danco Laboratories. In its papers, Danco had documented the massive economic harm it would suffer if Judge Kacsmaryk’s ruling was allowed to go into effect, and the regulatory hurdles (some might even say “regulatory chaos”) it would have had to surmount to mitigate that damage. To this, Alito relied upon the rather remarkable view that Danco would suffer that harm only if it … complied with the law. In his words:

That would not take place, however, unless the FDA elected to use its enforcement discretion to stop Danco, and the applicants’ papers do not provide any reason to believe the FDA would make that choice. The FDA has previously invoked enforcement discretion to permit the distribution of mifepristone in a way that the regulations then in force prohibited, and here, the Government has not dispelled legitimate doubts that it would even obey an unfavorable order in these cases, much less that it would choose to take enforcement actions to which it has strong objections.

This is one of the most remarkable passages I’ve ever read in an opinion by a Supreme Court Justice. First, the Court has never suggested that a party must show that it will be prosecuted to show that a law that clearly applies to it (and induces it to take actions to avoid violating it) causes harm. Second, even if this FDA would not enforce the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act against Danco in a world in which Judge Kacsmaryk’s order was in effect, that’s no guarantee that a future FDA wouldn’t. And if you’re Danco (or its investors, or its insurers, or its counterparties, or…), that specter is not remotely hypothetical. Given the current political climate, it would be more than a little foolish to assume that what’s true today will be true as soon as 2025 (which would still be within most statutes of limitations). Third, even if Danco were willing to risk future liability, what about prescribing physicians and pharmacists, without whom Danco’s hypothesized willingness to flout the law would be pointless?

But then there’s the bolded passage—and the remarkable assertion that “the Government has not dispelled legitimate doubts that it would even obey an unfavorable order in these cases.” You’ll note that Alito cites to precisely zero authority either for the “legitimate doubts” or for the government somehow having an obligation to “dispel” those doubts. Yes, members of Congress (from both parties) have suggested that the Biden administration shouldn’t follow an adverse ruling in the mifepristone case. But not only has no one in the executive branch even hinted that such a move was remotely in the cards; the White House specifically poured cold water on the idea. Near as I can tell, it’s been 162 years since the last time a President directly ignored a court order—and, right-wing fever dreams notwithstanding, I don’t exactly see President Biden or Attorney General Garland as likely heirs to the Merryman precedent.

Against that backdrop, it’s hard to imagine where Justice Alito got these “legitimate doubts” from (except, perhaps, right-wing media). Suffice it to say, before a Supreme Court Justice (let alone one with prior executive branch experience) publicly levels such a charge against the incumbent administration, it might behoove them to provide some evidentiary support. And even then, this argument still rises and falls on the novel view that a party can’t show irreparable harm unless the current executive publicly commits to enforcing the relevant law against them. It’s just wrong on so many different levels.

***

In all, it’s hard to look at Justice Alito’s dissent and not agree with Will Baude’s typically thoughtful take from Saturday over at Volokh Conspiracy—that rushed opinions like Alito’s reinforce why it’s not a good idea for the Court to be deciding significant legal questions through such an abbreviated process. The compressed schedule (which Alito himself played a big part in compressing by putting arbitrary deadlines on his administrative stays) does not appear to have served Alito well in the mifepristone case—a point that his dissent unintentionally but emphatically drives home.

SCOTUS Trivia: The Court’s Other Mifepristone Case

Most readers may not know that Friday was actually the second time that the Supreme Court has stayed a lower-court ruling respecting access to mifepristone. In January 2021, just before President Biden came to office, the Court granted a stay to the federal government in a case called FDA v. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. In that case, doctors had challenged the FDA’s refusal, at the height of the COVID pandemic, to relax the in-person dispensation requirements for mifepristone (the FDA would later relax those requirements itself). A district court in Maryland (where the FDA is headquartered—imagine that) had sided with the challengers, and the Fourth Circuit had refused to stay the injunction pending appeal.

The earlier mifepristone ruling is telling (and forms the basis for this week’s trivia) because the Court sat on the Trump administration’s emergency application for a remarkably long period of time—20 weeks from the day it was filed to the day it was resolved. (The delay was almost surely related to Justice Ginsburg’s death, which likely left the Justices divided 4-4.) In the meantime, while the mifepristone case was sitting on the emergency docket, the Court (1) agreed to conduct plenary merits review in Trump v. New York (a dispute over whether reapportionment data provided by the Secretary of Commerce could exclude undocumented immigrants); (2) received full briefing from the parties and numerous friends of the Court; (3) heard oral argument; and (4) handed down a decision on the merits. From start to finish, that entire process took 87 days—53 days fewer than the mifepristone case.

In other words, the earlier mifepristone case reinforces how quickly the Court can hear and resolve a case on the merits docket—at least if and when it wants to do so.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning at 8 ET.

Happy Monday, everyone! I hope you have a great week.

Opinion assignments are made by the senior Justice in the majority. That’s always the Chief Justice if he’s in the majority. And if he’s not, then the power to assign the majority opinion would go to Thomas, then Alito, then Sotomayor, in that order. And it would hardly be surprising if they kept some of the juicier assignments for themselves.

I had always thought that Justice Barrett’s cryptic concurrence in Does (which Justice Kavanaugh joined) was a signal from the then-junior Justice that she had perhaps been overzealous in when she had voted for emergency relief during her first Term on the Court, and that she intended to exercise more discretion going forward. The data, such as it is, bears this out, and by invoking that opinion in this part of his dissent, Alito seems to be reading it the same way.

One possible explanation for the lack of explanation is a lack of consensus among the 5–7 Justices in the majority as to the strongest basis for granting a stay. If some but not all were willing to express doubts about standing, avoiding the appearance of disagreement might have counseled in favor of silence.

Much to agree with here -- but just to double down on the pedantry, Alito’s quote from Kagan’s opinion isn’t a situation in which the usual Bluebook conventions would require an ellipsis to indicate his omission. The quote from Kagan’s opinion is being used as a clause in Alito’s own sentence (rather as a full sentence in Alito’s text) so no indication of the omission is required.

Thanks for an in-depth analysis of the stay, and Alito’s dissent. We talked about the dissent today, and some called it a type of advisory opinion. It’s crystal clear where Alito stands when this case returns in the future.