20. "Munsingwear Vacaturs"

A dissent from Justice Jackson criticized the Court's growing use of summary orders to wipe away lower-court rulings after appeals become moot. If anything, she understated the problems.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

The first week of the Court’s March 2023 argument session came and went without too much drama. Monday’s Order List included no new grants of certiorari and no especially high-profile denials. And although the Court issued its seventh signed decision in an argued case, Justice Gorsuch’s brief, unanimous opinion in Luna Perez v. Sturgis Public Schools (on whether the exhaustion requirement of the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act also precludes unexhausted claims brought under the Americans with Disabilities Act) isn’t exactly going to go down as one of the Term’s more significant rulings.

Instead, the only especially noteworthy ruling to come out of the Court last week was a four-page dissent from Justice Jackson in Chapman v. Doe, in which she objected to the majority’s summary grant of certiorari and vacatur of the ruling below under the so-called “Munsingwear” doctrine. If you’re wondering what the Munsingwear doctrine is or why Justice Jackson is (understandably) concerned about its recent use, read on.

The Justices are back on the bench this morning for more oral arguments, with orders from last Friday’s Conference expected at 9:30 ET today, and one or more opinions in argued cases expected at 10:00 ET tomorrow. It also seems likely that the Court will rule sometime this week on West Virginia’s pending application for emergency relief to put back into effect its ban on participation in women’s sports teams at public schools by transgender women. The fact that briefing on that application has been complete since Wednesday with no ruling from the Court may well be a sign that at least someone is writing separately—although we won’t know who or why until the order is issued (which could be at any time).

The One First Long Read: Munsingwear

The “Munsingwear vacatur” is one of those classic technical elements of Supreme Court practice that’s usually too obscure to receive much public discussion (here’s now-D.C. Circuit Judge Pattie Millett on the subject for SCOTUSblog in 2008). Like many of the Court’s other procedural practices, that’s unfortunate—because technical, procedural rulings from the Court can often produce significant downstream substantive and/or practical effects, and Munsingwear vacaturs are a textbook example of the phenomenon.

Let’s start at the beginning: The problem that Munsingwear vacaturs exist to solve is easy to describe: If A sues B for an injunction and B stops the complained-of conduct before the court can rule, that doesn’t moot the case; there’s a long-recognized exception to mootness doctrine for cases of “voluntary cessation,” i.e., when the reason why the challenged conduct stopped is because the defendant voluntarily stopped it. But what if the court rules for the defendant, the plaintiff appeals, and it’s only then that the defendant ceases the complained-of conduct (after he won)?

In those circumstances, the defendant’s actions may not have mooted the lawsuit, but they do moot the appeal—depriving the plaintiff of an opportunity to persuade the appellate court that the district court was wrong. Thus, the plaintiff is left with an adverse judgment that binds it in future cases—and bars relitigation of the same issues in a future suit under principles of “res judicata” or claim preclusion—even though he never had a chance to appeal. That’s pretty unfair. And where the case involves an appeal from a court of appeals to the Supreme Court, the lower-court decision doesn’t just bind the parties; it also will (usually) have precedential value in other cases within that jurisdiction.

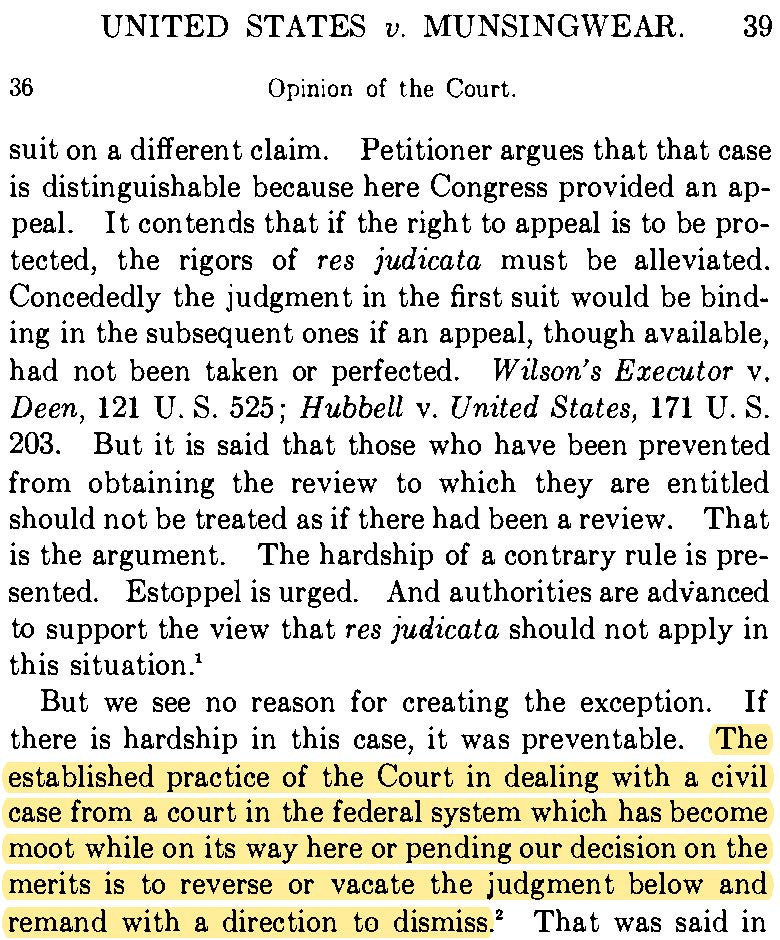

Recognizing these significant fairness problems in a 1950 case called United States v. Munsingwear, Inc., the Court derived from traditional equitable principles and its own prior jurisprudence the idea that “[t]he established practice of the Court in dealing with a civil case from a court in the federal system which has become moot while on its way here or pending our decision on the merits is to reverse or vacate the judgment below and remand with a direction to dismiss.” In other words, when pending appeals become moot, the way to avoid such unfairness to the party that lost below is to vacate the ruling they are seeking to challenge—so that it no longer stands as a binding precedent—and then direct the lower court to dismiss not just the appeal, but the entire dispute.

But as Munsingwear itself stressed, this “rule” should be limited to cases in which the equities justify it. Thus, in the very case in which the Court articulated the now-eponymous rule, the Justices refused to apply it—holding that the federal government had slept on its rights and had not proceeded in the lower courts in a manner that entitled it to a vacatur and dismissal from the Supreme Court (instead of appealing from the adverse appellate ruling, the government had filed a second suit and unsuccessfully argued that it shouldn’t be bound by the judgment in the first). In other words, Munsingwear vacaturs are not appropriate in cases in which the party that lost below is in some way responsible for the mootness of the appeal (including by not pursuing it in a timely manner); their hands, at that point, are not procedurally clean.

Among the four people who actually spend time thinking about Munsingwear, there’s some debate about whether and to what extent it should apply in cases in which the mootness is the fault of neither party—and results from a true matter of happenstance. But the principal objection Justice Jackson voiced last week is to the Court’s growing use of Munsingwear vacaturs when the party that lost bears some responsibility for the mootness. And Chapman v. Doe is a good illustration.

In a nutshell, Doe, a minor, had sought a judicial bypass under Missouri law so that she could obtain an abortion without her parents’ notification. Her request was (quite egregiously) rejected by the court clerk, a ruling she sought to challenge in a civil suit for damages for violating her federal constitutional right to an abortion under Roe. The Eighth Circuit rejected Chapman’s claim that she was entitled to immunity and remanded for further proceedings. Then the Supreme Court decided Dobbs, effectively vitiating Doe’s theory of the case. At that point, Doe and Chapman agreed to enter a joint stipulation of dismissal in the district court, so the only remaining question was what to do with the Eighth Circuit’s (precedential) ruling about why Chapman wasn’t entitled to immunity.

And as Justice Jackson explained in dissenting from Monday’s order vacating the Eighth Circuit ruling, “the equities generally do not favor Munsingwear vacatur when the party requesting such relief played a role in rendering the case moot.” Critically, Chapman could have declined to settle the case, and instead asked the Supreme Court to vacate the Eighth Circuit’s decision and remand in light of Dobbs (a step in which the Court would surely have acquiesced). Given that Munsingwear vacaturs are discretionary, and that Chapman had other avenues of preserving her rights, it should have followed, pace Justice Jackson, that the Court decline to provide such a vacatur here (and simply deny certiorari), even if the parties both supported such a disposition.

The problem with granting a vacatur in a context like this is, per Jackson’s dissent, two-fold: First, it ignores the extent to which “judicial decisions are valuable and should not be cast aside lightly, especially because judicial precedents ‘are not merely the property of private litigants,’ but also belong to the public and ‘legal community as a whole.’” Simply because Doe was willing to have the Eighth Circuit’s ruling vacated ought not to suffice given the broader implications of the ruling for other Missourians (and pregnant minors in other states within the Eighth Circuit).

Second, and more troublingly, again per Justice Jackson, “Injudicious awards of Munsingwear vacatur can also incentivize gamesmanship, as it, for example, enables parties to disclaim potential mootness before the lower court, and, if unsuccessful on the merits at that stage, argue mootness on appeal to eliminate the adverse decision through vacatur.” It also takes the government off the hook for changing policies that lower courts have blocked—since it can point to the change as a justification for vacating the lower-court ruling rather than having to persuade the Justices that the lower court was, in fact, wrong.

This may seem like an awful lot of ink to spill on a dry, technical point. But the significance of this debate has only increased since 2017. Indeed, Justice Jackson’s dissent noted that the practice is on the rise in recent years. And although she didn’t provide a source for that claim, the literature backs it up. A forthcoming Florida Law Review article by law professors Lisa Tucker (Drexel) and Michael Risch (Villanova) reports that there have been more Munsingwear vacaturs in the five-plus years since Justice Gorsuch joined the Court in 2017 than there were in the 22 preceding years—from 1994 through 2016.

More alarming still, as Tucker and Risch note, is the partisan valence of the new flurry of Munsingwear orders. Indeed, a November 2022 New York Times op-ed by Tucker and Stefanie Lindquist notes that, of the 13 Munsingwear orders issued by the Court in 2021 and 2022, 12 of them wiped away lower-court decisions that could fairly be characterized as liberal-leaning; only one wiped away a conservative lower-court ruling. In other words, Tucker and Risch argue, the Court at least appears to be using Munsingwear orders (which, by tradition, are summary procedural rulings with no analysis) to wipe away lower-court rulings with progressive partisan valences but not those with conservative partisan valences.

To be sure, it’s a small data set. And at least one explanation for the alarming pattern Tucker and Risch document is the flurry of Munsingwear vacaturs in cases challenging Trump administration policies after the Biden administration came to office (which, as I noted at the time, was itself an unusual cluster even for a cross-party presidential transition). Almost all of those cases involved lower-court rulings against Trump—so that the vacaturs were all necessarily in one direction.

But whether this data suggests a pattern or a coincidence, the two larger points remain: First, here’s yet another current context in which the Justices are more willing to use procedural orders that produce substantive effects than at any prior point in the Court’s history. (In this respect, Munsingwear is another useful example of the growing significance of the shadow docket—and why I hope my forthcoming book on the subject makes at least something of a dent.) And at least on their face, the orders tend to wipe away lower-court rulings that skew progressive, with less willingness to provide the same relief vis-a-vis rulings that skew conservative.

And second, partisan valences aside, the Court is, as Justice Jackson’s dissent demonstrates, clearly issuing Munsingwear vacaturs in contexts in which the party that lost bears at least some responsibility for the mootness—not just in Chapman, but in challenges to numerous federal policies, as well. That runs directly counter to what the Court has previously said about Munsingwear. Here’s Justice Scalia writing for a unanimous Court in 1994 in U.S. Bancorp Mortgage Co. v. Bonner Mall Partnership:

The principles that have always been implicit in our treatment of moot cases counsel against extending Munsingwear to settlement. . . . Where mootness results from settlement, . . . the losing party has voluntarily forfeited his legal remedy by the ordinary processes of appeal or certiorari, thereby surrendering his claim to the equitable remedy of vacatur. The judgment is not unreviewable, but simply unreviewed by his own choice. . . .

It is true, of course, that respondent agreed to the settlement that caused the mootness. Petitioner argues that vacatur is therefore fair to respondent, and seeks to distinguish our prior cases on that ground. But that misconceives the emphasis on fault in our decisions. That the parties are jointly responsible for settling may in some sense put them on even footing, but petitioner's case needs more than that. Respondent won below. It is petitioner’s burden, as the party seeking relief from the status quo of the appellate judgment, to demonstrate not merely equivalent responsibility for the mootness, but equitable entitlement to the extraordinary remedy of vacatur. Petitioner’s voluntary forfeiture of review constitutes a failure of equity that makes the burden decisive, whatever respondent's share in the mooting of the case might have been.

In other words, some special showing is required when the party that lost below bears some responsibility for the mootness. Thus, vacating a lower court decision blocking a government policy because the government changed the policy is perhaps the paradigmatic case in which Munsingwear vacatur is not appropriate. And yet, that represents the bulk of the vacaturs we’ve seen since 2021. At the very least, given U.S. Bancorp and similar statements in prior opinions of the Court, it would certainly behoove the Justices to explain why they’ve changed their mind on this technical but significant procedural point (assuming, that is, that they have).

Just to say the quiet part out loud, Munsingwear vacaturs are often a convenient dodge. Wiping away a lower-court ruling without issuing one of their own lets the Justices have their cake and eat it, too. It may therefore be no surprise that, as the Court’s docket has become more dominated by ideologically divisive cases in recent years, the allure of Munsingwear vacaturs has grown.

But like much of the Court’s other behavior on the shadow docket, the existence of good prudential reasons for the Justices’ behavior doesn’t obviate them of the responsibility to either follow their own previously articulated rules in such cases, or to explain why they’re no longer doing so. And given the rich normative justifications for both Munsingwear and its limits, my own view is that Justice Jackson had it exactly right; here’s hoping some of her colleagues take her concerns (and these additional ones) more seriously going forward.

SCOTUS Trivia: Happy Birthday, Justice O’Connor

As Duke professor Marin Levy pointed out on Twitter, Sunday was Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s 93rd birthday. That puts the Court’s first woman Justice into some comparably rare territory. Only three other Justices lived past their 93rd birthday: Justice John Paul Stevens (the longest-lived Justice), who was 99 at his 2019 passing; Justice Stanley Reed, who was 95 at his death; and Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., who died two days shy of his 94th birthday. (As I noted in an earlier bonus issue, my favorite recent book about the Court is Evan Thomas’s biography of O’Connor, titled “First.”)

Reed also appears to be second in the race for the longest-lasting retirement; he retired from the Court in February 1957, but lived until April 1980—over 23 years later. Justice James Byrnes, who served briefly in 1941–42, is the clubhouse leader in this esoteric category; he lived another 29.5 years after his retirement from the bench. O’Connor wouldn’t catch Byrnes for that mark until 2035.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning at 8 ET.

Happy Monday, everyone! I hope you have a great week.

I am still having trouble wrapping my mind around what exactly a Munsingwear Vacautr DOES. Could you create some hypotheticals (perhaps along the lines of Joyce Vance's Chicken explanation of conspiracy law) that show its use in a) situations where the equities demand it) and b) situations where the equities don't really?

I’m with Susan Linehan, more examples please.

What action in your example of A and B ends up mooting the appeal? When a higher court vacates the lower court decision, does that allow the parties to litigate again, thus preserving rights to appeal?