19. When There Are Nine...

A look at the historical evolution of the size of the Supreme Court, and some of the reasons why even progressives ought to be wary about expanding it today

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

Note also that this week’s bonus content, which will drop Thursday morning, will feature the first of our promised “AMAs” (ask me anything). So if you have questions you’d like me to address on Thursday, please either post them as comments to this post or send them to me via e-mail (and, if the latter, indicate whether you’re willing to be publicly identified or not).

On the Docket

As expected, it was a quiet week at the Court, with no opinions in argued cases and only a single anodyne order relating to an upcoming oral argument. Instead, the headline at the Court last week was the formal Supreme Court Memorial and Bar Memorial for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, which took place on Friday afternoon. The Supreme Court’s webpage includes audio of the Court’s 23-minute formal session, video of the 52-minute Bar Memorial that preceded it in the Court’s Great Hall, and transcripts of both.

This week looks to be quite a bit busier. A regular Order List is expected at 9:30 a.m. EDT today; one or more opinions in argued cases are expected at 10 EDT tomorrow; and the Justices will be back on the bench to kick off their March argument calendar, including four arguments this week and six next week.

We may also hear from the Court sometime this week on West Virginia’s pending emergency application to put back into effect a state law that prohibits transgender women from participating in varsity athletics at public schools across the state. The plaintiff’s response is due today at noon EDT.

The One First Long Read: The History of (and Arguments Against) Expanding the Court

The Constitution is famously silent about how many Justices sit on the Supreme Court. There’s a pretty good argument that it requires at least one (Article I, Section 3, Clause 6 contemplates a “Chief Justice” to, if nothing else, preside over the Senate during presidential impeachment trials). But how many seats there should be beyond one is left, entirely, to Congress’s discretion. (This delegation is in marked contrast, for instance, to most state constitutions—which expressly fix the size of their supreme courts.)

In other words, whether Congress can expand the Supreme Court beyond its current size of nine Justices (a Chief Justice and eight Associate Justices) is a political question, not a legal one. And although recent years have led many progressives to clamor for just such an expansion, there are reasons in the history of debates over the Court’s size for even those who are unhappy with the current Court to be wary of such a reform.

A. The Evolution: From 1789–1869

Section 1 of the Judiciary Act of 1789 created six seats on the Supreme Court. It may seem unusual to have an even number of Justices on the Court, but Congress was focused, at least initially, not on the specter of closely divided rulings, but on the dual role the Justices would play—not just as part of the Supreme Court, but as Circuit Justices who, together with the local district judge, would exercise the judicial power of the federal circuit courts under the 1789 Act. That Act created three circuits, each of which was staffed by two Justices, hence the total of six.

As part of the Judiciary Act of 1801 (a.k.a., the Midnight Judges Act), the lame-duck Federalist Congress in February 1801 sought to prevent the next President (whose identity wasn’t yet clear) from filling the next vacancy. Thus, Congress eliminated one of the five Associate Justice positions—effective whenever the next vacancy occurred. Thus, there was a powerful early precedent for Congress manipulating the size of the Court for transparently partisan political aims. And although this would’ve been a poor fit for the circuit-based division of Justices, the 1801 Act also absolved the Justices of that responsibility—creating standalone circuit courts to be staffed by standalone circuit judges.

The Democratic-Republicans, upon coming to power, quickly repealed the Judiciary Act of 1801—restoring the Court to six seats before a vacancy ever occurred (the next vacancy occurred upon the resignation of Justice Alfred Moore in January 1804). Congress also restored the practice of circuit riding while restructuring the circuits into six circuits—with one Justice per court. Then, in 1807, when Congress created a seventh circuit court, it also added a seventh seat to the Court—setting a precedent for tying the size of the Court to the number of circuits. That precedent was followed again in 1837, upon the creation of the eighth and ninth circuit courts. And when Congress created a tenth circuit court in 1863, it added a tenth seat, as well. (As I noted in a prior issue’s trivia, there were two brief periods during which ten Justices appear to have sat together.)

Thus, for nearly a half-century, Congress followed an ostensibly neutral pattern of pegging the size of the Court to the number of circuits. Relatedly, the understanding accompanying that practice was that each of those geographic subdivisions should be represented on the Court—hence why President Lincoln picked (Democratic) California Supreme Court Justice Stephen Field for the new 10th seat in 1863.

That understanding fell by the wayside in 1866, when the Radical Republican-controlled Congress, as part of its power struggle with President Andrew Johnson, passed legislation reducing the size of the Court to seven seats. As with the 1801 Act, the legislation eliminated seats only once they became vacant. Thus, it immediately eliminated one seat (the vacancy caused by Justice John Catron’s May 1865 death); and it eliminated a second seat upon the July 1867 death of Justice James Wayne—reducing the Court to eight Justices for the duration of Johnson’s presidency.

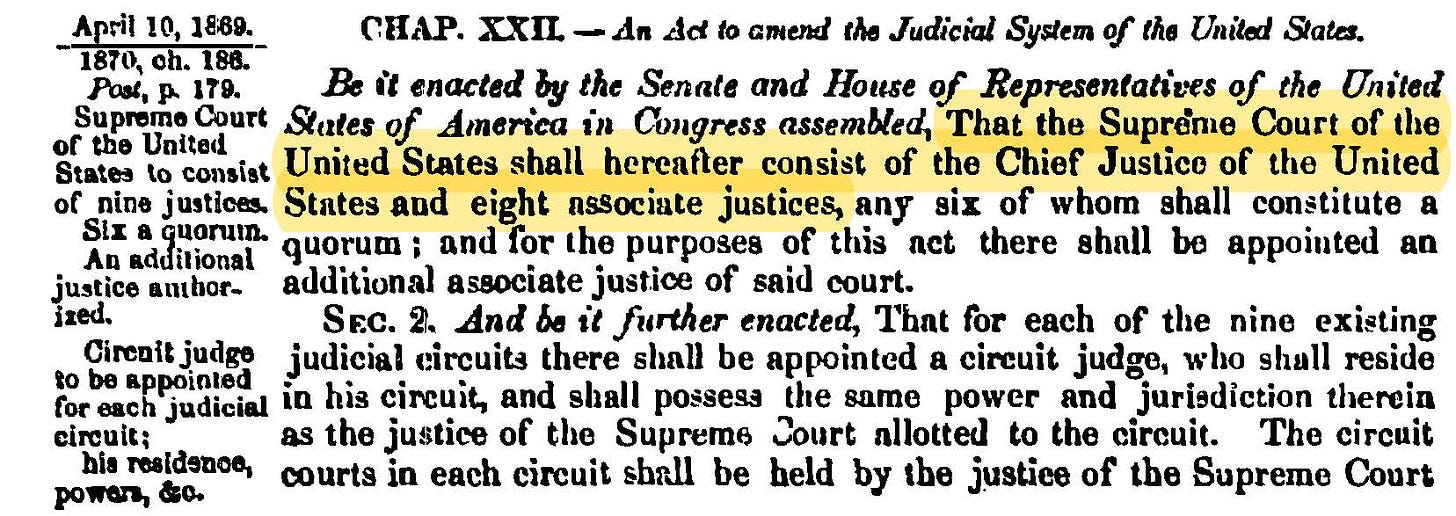

Before a third vacancy could occur, President Grant was sworn into office and, just five weeks later, Congress promptly restored the Court to nine Justices. Indeed, the Judiciary Act of 1869, enacted on April 10, was the last time Congress changed the Court’s size (adding the seat that would be filled by Justice Joseph Bradley).

And, in an important break from precedent, the 1869 Act untethered the size of the Court from the number of circuits—thereby setting a precedent for keeping the Court at nine seats even as lower courts expanded.

B. The Key Non-Expansions: 1929 and 1937

The first key test of that precedent came in 1929, when Congress created the new Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals (the ten circuits that existed in 1863 included the D.C. Circuit) by cutting the old Eighth Circuit in half. Critically, the bill creating the Tenth Circuit did not add an additional seat to the Supreme Court. Thus, for the first time, Congress created a new circuit court without expanding the Supreme Court.

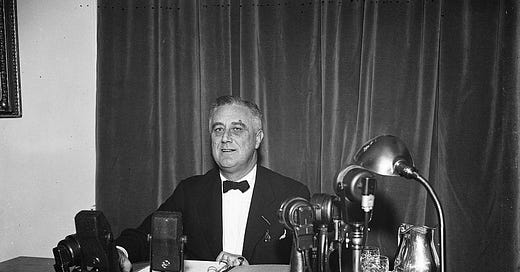

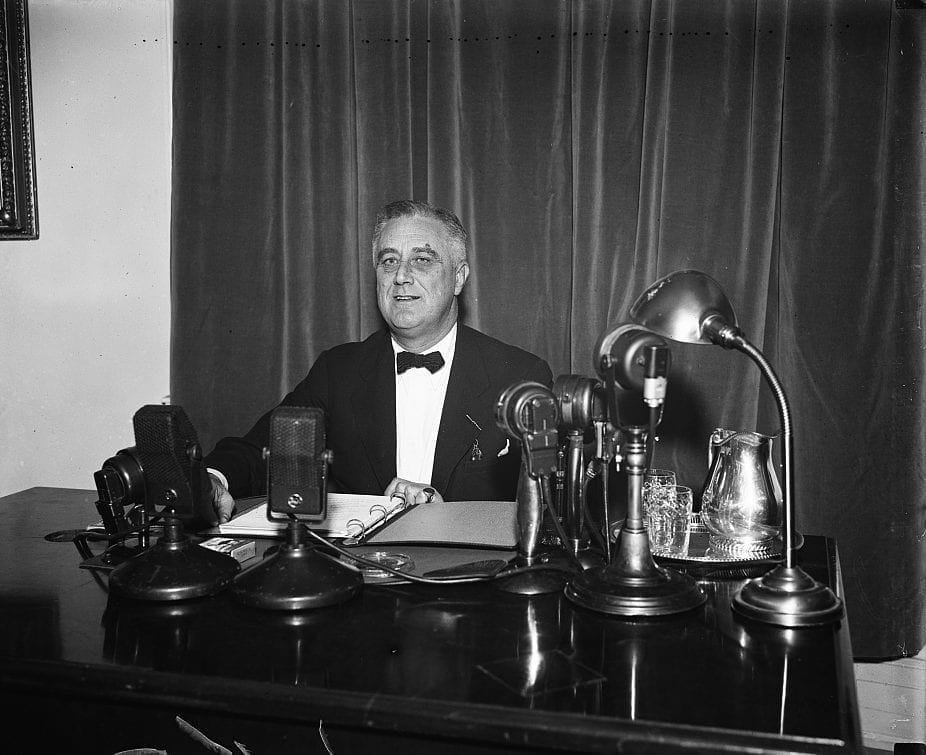

The more famous moment came eight years later, with the introduction and demise of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s infamous “court-packing” plan. Having won an enormous electoral mandate in the Election of 1936 (in which he had largely run against the conservative Court), FDR, in a March 9, 1937 “Fireside Chat,” proposed legislation that would create one new judgeship on every federal court for each active judge over the age of 70. Not-very-coincidentally, that would have led to the creation of six new seats on the Supreme Court, for a new total of 15.

Opposition to FDR’s plan came from everywhere—including Democrats in Congress and even the Court’s sitting Justices. Ultimately, the plan was defeated—although not before the famous “switch in time that saved the nine,” i.e., Justice Owen Roberts’s decisive vote in West Coast Hotel v. Parrish to uphold Washington State’s minimum wage law for women (just two years earlier, Roberts had joined the conservative Justices in striking down a similar New York law, so his shift was an unmissable harbinger that the dam had broken).1 There is a rather … heated … academic debate about whether Roberts had blinked because of FDR’s proposal (on one hand, Roberts initially voted at Conference to uphold Washington’s law before FDR formally unveiled his plan; on the other, Court reform was quite clearly already in the water). What no one denies is that, although FDR lost the battle, he won the war; within four years, eight of the Court’s nine Justices would be Roosevelt appointees.

C. Debating Expansion Today

The near-universal opposition to FDR’s plan is a good segue to contemporary proposals to add either two or four seats to the Supreme Court. The proposals have at their core some combination of the need to restore ideological balance to the Court and/or the need to retaliate against Republicans for (1) refusing to even hold an up-or-down vote on President Obama’s nomination of then-Judge Merrick Garland to fill Justice Scalia’s seat; and (2) going back on the very principle on which (1) purported to depend—no Supreme Court confirmations in a presidential election year—to hustle then-Judge Amy Coney Barrett onto the Court after Justice Ginsburg’s September 2020 death.

Unlike many critics of contemporary proposals to expand the Court, I have at least some sympathy for these objections. Both the Garland and Barrett episodes reflected a Republican-controlled Senate throwing principle and consistency to the wind in the name of partisan political expediency, and it takes more than a little chutzpah to believe that only Republicans are allowed to do that (or, just as significantly, that Democrats have never done that themselves). Simply put, I get why, to so many, turnabout is fair play when it comes to proposals to expand the Court.

My concern, as reflected in the debate over FDR’s Court-packing plan, is what happens if these proposals succeed—and the precedent it would set for the Court going forward. If Congress increases the size of the Supreme Court for transparently partisan political reasons, it would cement the idea that the Justices are little more than politicians in robes, and that the Court is little more than an additional—and very powerful—arm through which partisan political power can be exercised. To be sure, many Americans already hold this view of the court. But expanding the Court for transparently partisan reasons would only make things worse, especially if it sets a precedent for future Congresses to do the same.

The problem is that Court expansion won’t end with the next proposal to expand the Court; the next time Republicans control both chambers of Congress and the White House, they would presumably push through legislation to add four new seats to the Court. And Democrats, when the tables have turned, will add six seats. And in a matter of years, the Court would have 9 + 2(n+2) Justices—and no credibility.

To some, of course, destroying the legitimacy of the Supreme Court (especially the current Court) may be a feature of these proposals, not a bug. So be it. But even those who don’t see their views represented among a majority of the current Justices should have an interest in preserving the Court’s long-term authority to check the political branches—authority that partisan Court expansion would necessarily, and, I fear, irrevocably, erode.

Indeed, if one of the most important justifications for an independent, un-elected judiciary is the ability to protect the rights of minorities against the tyranny of the majority, a Court that is beholden to whichever party is currently in power would likely lack both the inclination and the legitimacy to stand up to the political branches. In the long term, my own (perhaps misbegotten) view is that that’s too steep of a price to pay.

SCOTUS Trivia: The Shortest (and Tallest) Justices

The rare chance to mention Justice Alfred Moore is perhaps the best excuse I’ll ever have for an especially trivial installment of SCOTUS trivia: Identifying the tallest and shortest Justices to serve. (As someone who is 6’8”, I’ve always been especially interested in the heights of key historical figures.)

As you may already have guessed, Moore (who served from 1800–04) takes the prize for most vertically challenged of the Court’s Justices. Contemporary sources claim that he stood only four feet, five inches tall (i.e., the same height as my seven-year-old daughter).

As for the tallest Justice to serve, that distinction appears to belong to Justice Horace Gray (who served from 1882–1902), although sources differ as to whether he was 6’4” or 6’6”.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, or want to participate in this week’s AMA, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning at 8 ET. And, once again, it will feature my responses to your questions—so please fire away, whether in the comments below or via e-mail.

Happy Monday, everyone! I hope you have a great week.

Interestingly, one part of FDR’s proposal survived: Congress in 1937 took away the power of individual federal district judges to enjoin federal statutes or policies on constitutional grounds, requiring that such suits instead be heard by three-judge district courts. That requirement was eliminated in 1976, but might be worth revisiting—as I argued last year in a New York Times op-ed.

Professor, I usually agree with your side in debates like this, but I wonder if your arguments against (contemporary proposals for) court expansion too lightly bypass the fact that Congress has the power/responsibility to check the Court's excesses, and not just the other way around? The current Court (as you yourself have brought to a lot of people's attention) seems to be aggravating to itself more power, if not formally then practically, by playing fast and loose with procedures and precedents when it suits certain objectives. Certainly I think expanding the court would be a radical option, but one that ought to be in Congress' toolbox if the Court frustrates it in ways that are hard to explain through evenhanded application of the law, and it would be entirely consistent with checks and balances. And I think there is in itself a danger to Congress being too hesitant to exercise that constitutional power, just as there is danger to being too willing to: it serves nobody to further politicise the courts, but if, in the face of a more and more aggressive Supreme Court, it continues to be treated like a third rail to check it, it negates the constitutional structure that allows each branch to hold the others to account.

Aside, because I don't want to just write a pretty long and slightly argumentative comment, I do sort of like the idea of an even-numbered Supreme Court. If the Court splits in halves on a question, maybe it's better to let it percolate around the lower courts a bit and have the Justices find more consensus before imposing a national rule. And if there were 12 Justices each could cover a geographic circuit, and nobody would have to be in the unenviable spot of being Circuit Justice for just the Federal Circuit.

In a serendipitous moment, I just read yesterday David M Kennedy's account of the Roosevelt "court packing." (The book, Freedom from Fear, is really eye-opening and rather different from the stories my father, a firm Roosevelt Democrat, and others have told of the whole New Deal). One of the problems with Roosevelt's plan was the almost sacred status the Supreme Court had in the 30s. That would be less of an issue today. He also tried to push his idea too far, applying it to all Federal Courts.

But as a form of term limits it could work. Roosevelt's plan only called for an additional justice if one who was over 70 refused to retire. If a sitting justice did retire, he would only be replaced-not have a spare added.

Today the age limit could be higher--75? 78? But since it would ONLY click into effect if a elder type refused to retire, it wouldn't necessarily have that round robin effect you worry about. It gets around the problem of term limits on a "lifetime" position.

Congress could simply decide by legislation whether someone new could be considered in the X months before an election. The senate might not have to APPROVE the candidate, but s/he should at least get a full hearing. And prevent the Kavanaugh Problem, the FBI could be REQUIRED to follow up investigating tips once a credible witness raised an issue of prior misconduct that might affect the Senate's choices and should be required to testify under oath as to its findings before confirmation can continue. (With some timeframe to keep it from dragging out indefinitely). Any of these things could benefit EITHER party and might not result in musical chairs.

It could also place limits on the "shadow docket," and on appeals of interlocutory decrees. And it could outline what specifically allows the use of the nationwide injunction. It is supposed to be for things that are emergencies (like Covid stuff) and should be applied only when the injunction does not impinge on state laws and state constitutions unless needed to deal with the emergency. Certainly the overturning of a decades old FDA approval is not an emergency. THAT case needs to go through the normal process of Circuit Court Appeals (including full panel decisions) and then an appeal for cert. And cert should be denied if there isn't a Federal Question regarding constitutionality or a split of authority between the circuits. Not sure how much of that can be accomplished by legislation, but some Congressional Guidelines could help.

Finally, the court may be able to overturn precedent, but should NOT be allowed to ignore a valid standing issue.