18. The Growing Abuse of Single-Judge Divisions

The Supreme Court may soon have an opportunity to weigh in on the growing practice of plaintiffs hand-picking the specific district judge who hears their lawsuit. It should condemn it.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

As expected, it was a fairly quiet week at the Court, with no oral arguments and no decisions in argued cases. The Justices agreed to take up one new case in last Monday’s Order List (a maritime insurance dispute), and, over no public dissents, they denied another last-minute request to halt an execution (this time in Texas), but that was about it. The Court also appeared to initiate a new (and ultimately harmless) practice of providing more permanent electronic versions of recently issued rulings—which, if nothing else, will make it easier for lawyers and law students to correctly cite recent rulings in their legal briefs.

This week is also shaping up to be fairly low key. There was no Conference last week, so no Order List is expected today (the Justices are set to meet again this Friday). The only big news may involve an incoming emergency application from West Virginia and the Alliance Defending Freedom (strange bedfellows to be sure), asking the Justices to put back into effect a West Virginia state law barring transgender women from competing on women’s sports teams at public secondary schools or colleges as a challenge to the law works its way through the courts. Given that, as Chris Geidner helpfully explains, the entire dispute appears to revolve around a single 12-year-old runner, it’s possible the Justices might view this case as not one that warrants their intervention. Then again, one of the real shifts in how the Court has used the “shadow docket” in recent years has come in similar contexts—where the only “irreparable harm” being suffered by the government was the fact that one of its laws had been (temporarily) blocked. So, stay tuned…

The One First Long Read: Judge Shopping

Careful readers of last Thursday’s bonus content were likely expecting today’s issue to focus on the size of the Court and the history of Court-expansion and Court-reduction proposals. I’m still planning to cover that topic in a forthcoming issue, but intervening events prompted a change in plans for today.

Instead, I wanted to write about an emerging phenomenon I’ve discussed elsewhere, but that has come back into the light this week for two unrelated reasons—both of which may soon put the matter before the Justices in one way or the other. The phenomenon is “judge shopping”—where plaintiffs are able to pick the specific judge who hears a specific case simply by manipulating where the case is filed. And although some variant of judge shopping has long been possible, what’s different about what’s happening today is how shamelessly the loophole is being exploited in cases with unavoidably partisan valences to judges who may well be ideological outliers among their peers.

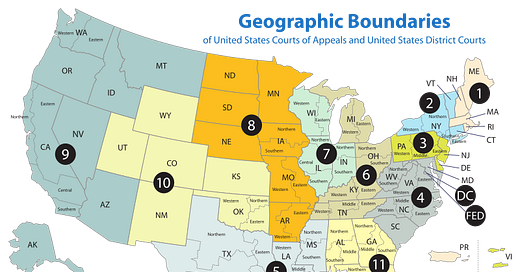

Let’s start at the top. There are 94 federal district courts; some states have just one (e.g., the District of Arizona), some have as many as four (e.g., the Northern, Southern, Eastern, and Western Districts of New York). By statute, just about all of them are further divided into some kind of subdivisions, either expressly called divisions (see, e.g., Texas, the four district courts of which are divided into 27 divisions); or through language that “court shall be held” in different geographic locales. The basic idea here is that, especially in large geographic areas, there should be enough federal courthouses to minimize the need for local parties (and jurors) to travel to a faraway jurisdiction.

But even though the 94 district courts are geographically subdivided by Congress, their dockets are not. Instead, Congress has left it to the district courts themselves to decide how to divide up business within their jurisdiction. In other words, federal venue rules created by Congress may lead a litigant to file a lawsuit in the Western District of Texas, but the Western District decides how that case should be assigned among its 11 active and five senior judges based upon where, within the Western District, it is filed.

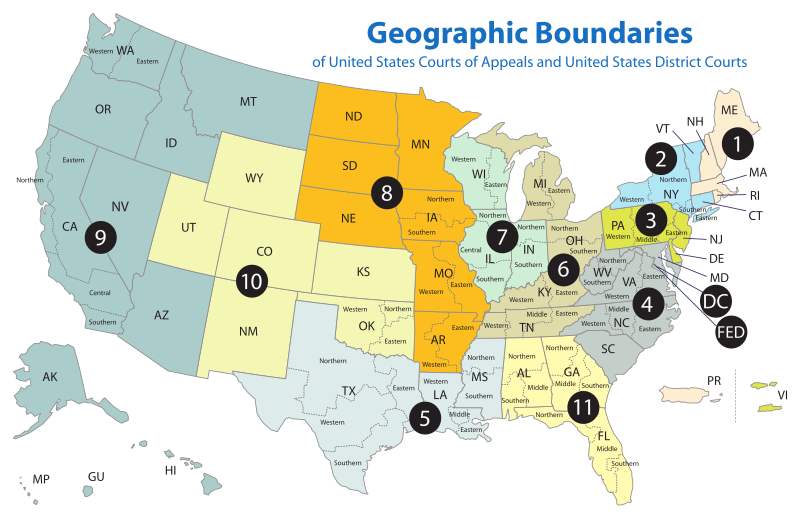

This is where judge shopping comes in. Some district courts have used their discretion to divide their business to do so geographically, so that judges are assigned to cases based upon which courthouse the cases are filed in. In districts with lots of judges and/or only a few subdivisions (e.g., the Southern District of New York), this still means random assignment, but perhaps random assignment among only a subset of the total judges in the district court. But at least some districts with a relatively high number of subdivisions compared to the total number of judges have gone the other way, having individual judges responsible for most or all new cases filed in particular geographic parts of the district. For instance, here’s how Texas’s 27 divisions are currently divided, including eight divisions in which a single judge hears *100%* of all new civil cases:

In other words, file a new civil case in the Amarillo division of the Northern District, and you’re guaranteed to draw Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk. Ditto Galveston and Judge Brown; Waco and Judge Albright; and, until recently, Victoria and Judge Tipton. To be clear, (1) Texas is not the only state with single-judge divisions; and (2) no statute prohibits this kind of assignment practice. But there are plenty of district courts that don’t follow it, and instead have random assignment even where that means judges from one part of the district have to be part of the “wheel” for cases filed and heard in another part—requiring the judges to regularly travel from their home chambers in order to hear cases. So single-judge divisions are not squarely prohibited, but they’re also by no means necessary.

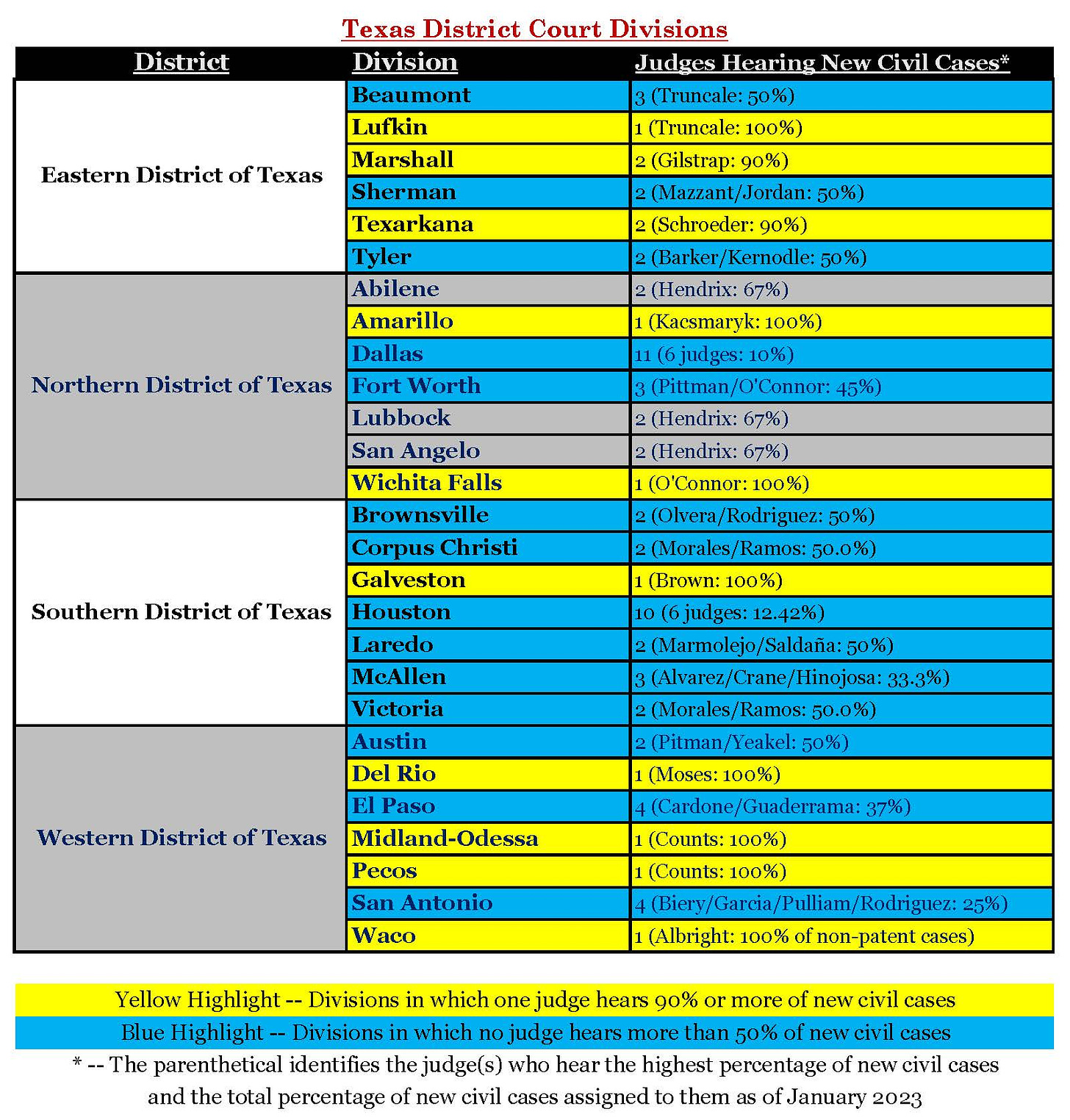

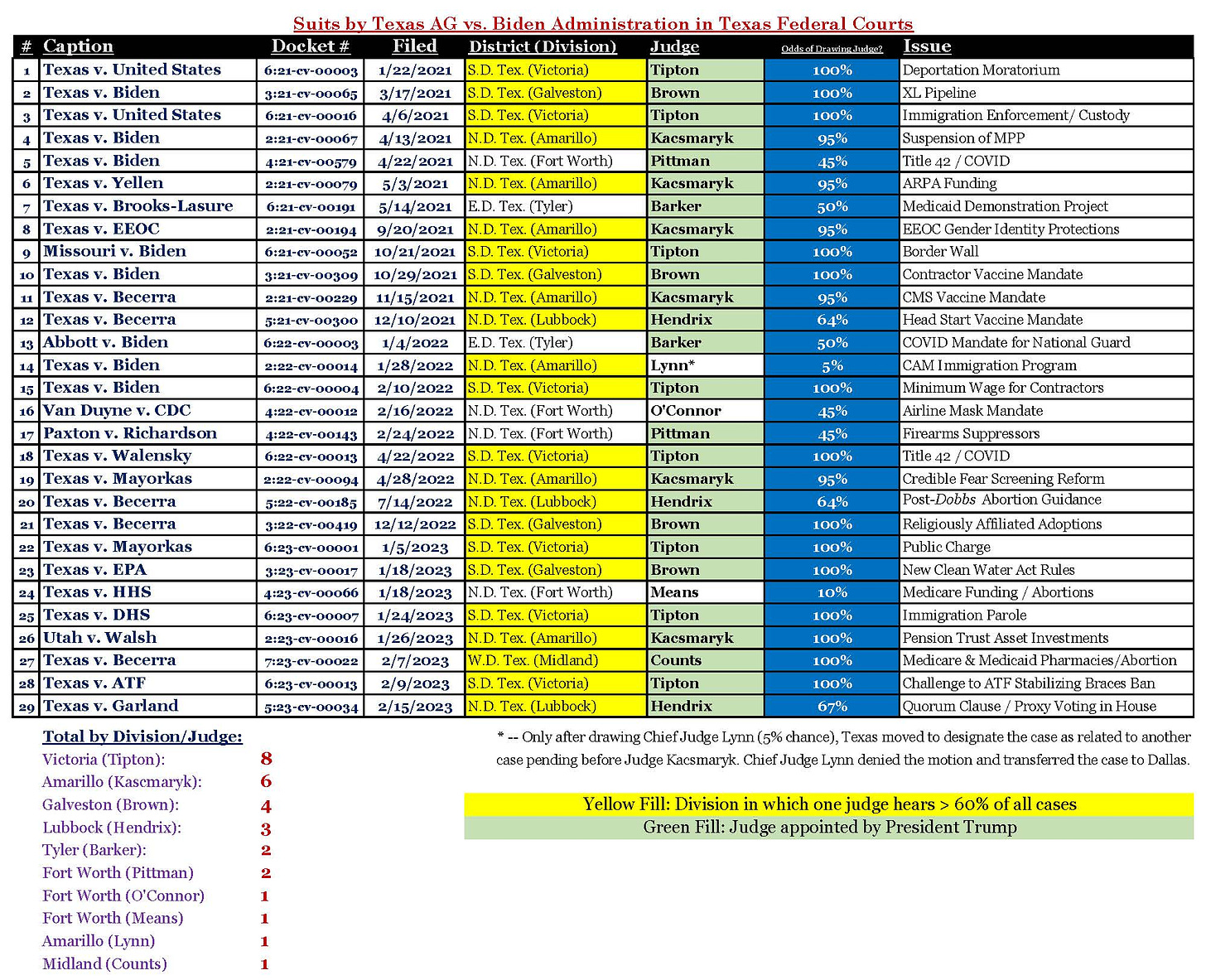

What’s changed in recent years isn’t the existence of single-judge divisions, but the transparent manipulation of them by repeat litigants. Take the State of Texas, as just one example. In just over two years, Texas has filed at least 29 different challenges to Biden administration policies in one of Texas’s federal district courts (it’s filed challenges elsewhere, too):

Of those 29 challenges, zero have been filed in Austin (where the Texas Attorney General is located, and/but there’s a 50/50 chance of drawing a district judge appointed by a Democratic/Republican President). Zero have been filed in Houston. Or Dallas. Or San Antonio. Or El Paso. Or in courthouses elsewhere along the border (even though many of these cases challenge immigration policies). Instead, Texas has filed its lawsuits in Victoria (8); Amarillo (7); Fort Worth (4); Galveston (4); Lubbock (3); Tyler (2); and Midland (1). And it has publicly admitted that it’s filing these lawsuits in these … un-obvious … locations because it wants these specific judges to hear them. Ditto the pending lawsuit by the “Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine” challenging the FDA’s approval of the abortion drug Mifepristone. In a challenge that could’ve been brought anywhere in the country, the Alliance incorporated itself shortly before filing the suit in Amarillo—and then filed suit there, where it was guaranteed to draw Judge Kacsmaryk.

Fast forward to last week, and the two developments that have perhaps started to tee this issue up for the Supreme Court. The first came in one of those 29 Texas v. Biden suits: Texas v. Department of Homeland Security, a challenge to a new immigration parole program that Texas filed in the Victoria Division of the Southern District at a point when it had a 100% chance of having the case assigned to Judge Drew Tipton. (The Southern District has since amended its division of business rules, albeit not apparently to respond to judge-shopping concerns.)

What makes the Texas v. DHS case different is that, for the first time, the Biden administration filed a motion to transfer the case, arguing that Victoria was an improper venue for the suit—and that, even if it was a proper venue, Texas’s apparent judge shopping and the convenience of the parties both supported having the matter transferred to a different district (or, at least, a different division within the Southern District, even one in which Judge Tipton could’ve been randomly drawn to hear the case). DOJ has since filed similar motions in two of Texas’s other cases, but this was the lead one.

On Friday afternoon, Judge Tipton denied DOJ’s motion. His written ruling basically concludes that, because DOJ refused to seek his recusal or otherwise argue that he was biased, it couldn’t carry its burden of demonstrating that Texas was engaging in judge shopping or that the interests of justice supported a transfer. Even though Texas conceded at oral argument that it filed in Victoria to draw Judge Tipton, and offered no alternative explanation for its broader pattern of litigation behavior, Judge Tipton effectively ruled that there couldn’t be anything wrong with such transparent manipulation of federal procedure unless there’s something wrong with the judge.

Then, on Saturday night, the Washington Post broke the news that, in the mifepristone case, Judge Kacsmaryk had apparently scheduled a hearing for this Wednesday but instructed the parties not to publicize the existence of the hearing until late Tuesday—presumably to minimize public awareness of, and public opportunities to witness, Wednesday’s proceedings.

What these developments have in common is that they both reinforce the problems with, and the flaws in the defenses of, judge shopping. Folks will have their own views about the impartiality of individual judges; the problem is the appearance it creates when litigants can hand-pick the judges to hear specific challenges to specific policies. Put another way, judge shopping is a problem even if the judges to whom these cases are being steered are acting consistently with judicial and ethical norms, entirely because it undermines public perception in the neutrality and impartiality of the judiciary even if the judges are doing their level best.

Thus, when Judge Tipton insists that he’s capable of fairly resolving the cases Texas keeps steering to his courtroom, he misses the point that it’s Texas’s behavior, not his, that creates the appearance of undue manipulation of the judiciary. Ditto the headlines about Judge Kacsmaryk’s efforts to keep a key hearing largely off the public radar. If it were a randomly assigned judge taking such an unorthodox procedural step, it would likely have registered quite differently than it did because it was the judge hand-picked by the Alliance Defending Freedom to hear a dispute that could have nationwide implications for the future of medication abortion.

To be sure, some commentators have attempted defenses of judge shopping, claiming that (1) it’s nothing new under the sun; (2) Democrats do it too; and (3) it’s no different from forum shopping—which is largely unavoidable in a legal system with relatively permissive venue and territorial jurisdiction rules, especially in suits against the federal government and/or its officers. With respect, these arguments are hogwash. First, although there did indeed used to be single-judge district courts (back when federal courts—and dockets—were much smaller), I’m not aware of any examples of nationwide claims being regularly steered to particular courts in order to capitalize upon the proclivities of specific judges (nor do these commentators offer any). Maybe that’s a function of the different nature of federal litigation (and the federal judiciary) in prior generations, but it’s a pretty significant distinction.

And with regard to the whataboutism claim re: Democrats during the Trump administration, this misses several key distinctions in the respective behaviors. Yes, Democratic state attorneys general brought a number of lawsuits against Trump policies (exploiting some of the same dilutions of state standing that I criticized two weeks ago). But (1) those suits were almost always brought in the state AG’s home courthouse (e.g., Hawaii filing in Honolulu; California filing in Oakland—which many may not realize is the location of one of the California Attorney General’s offices); and (2) none of those litigants regularly sought to file in single-judge divisions. In other words, the strongest charge that could be leveled is that Democratic AGs and private groups were engaged in forum shopping, not judge shopping. And even then, where would we prefer state AGs to file challenges to federal policies if not in either their home courthouses or D.C.?

To be sure, there are district courts in some of these jurisdictions in which every judge was appointed by a President of the same party (this is a larger issue across both parties traceable to the continuing prevalence of “blue slips”). But unless your view is that every judge appointed by a President of the same party will rule the same way in every case, it seems like there’s a meaningfully significant distinction between picking a relatively friendlier forum and literally hand-picking a specific judge. And even for those who don’t find that distinction relevant, it’s not usually the case in legal arguments that two wrongs make a right.

But perhaps the best evidence that transparent judge shopping ought to be condemned comes from a context with a less-partisan valence: patent disputes. After a 2017 Supreme Court ruling changed the standard for venue in patent cases, the district judge assigned to hear all new civil cases in the Waco Division of the Western District of Texas took steps to affirmatively attract patent plaintiffs to his courthouse—steps that were possible only because litigants were guaranteed to have cases filed in Waco assigned to that particular judge. As the Waco patent docket exploded (reaching 25% of all patent cases filed nationwide), the patent bar took notice—and, eventually, so too did Congress and Chief Justice John Roberts. Indeed, Roberts went out of his way in his 2021 Year-End Report to raise questions about the practice, noting that “the Judicial Conference has long supported the random assignment of cases and fostered the role of district judges as generalists capable of handling the full range of legal issues,” even as “the Conference is also mindful that Congress has intentionally shaped the lower courts into districts and divisions codified by law so that litigants are served by federal judges tied to their communities.” In his words, “Reconciling these values is important to public confidence in the courts.”

That message, at least, was received; last July, the Western District changed the rules for patent cases filed in Waco, so that new patent suits filed there would be (and are today) randomly assigned among every judge in the district. If there’s some explanation for why the practice was worth shunning and then foreclosing in patent cases but not in others, no one has yet provided it.

Beyond the Chief Justice addressing the practice in his administrative capacity, the issue has also worked its way onto the Supreme Court’s docket. In the unhelpfully but aptly named United States v. Texas, in which the Court heard oral argument last November, Texas is challenging the Biden administration’s immigration enforcement priorities—and successfully obtained a nationwide preliminary injunction against the policy from Judge Tipton, who it had a 100% of drawing when it filed the suit in Victoria. That manipulation came up during one exchange at oral argument between Justice Kagan and Texas Solicitor General Judd Stone, in which Kagan responded to Stone’s invocation of Judge Tipton’s factual findings in defending Texas’s standing to bring the lawsuit in the first place by noting that Texas had specifically picked him to hear the dispute, emphasizing “the backdrop of this case and what's going on here.”

What last week’s developments in the Texas v. DHS and mifepristone cases underscore is that the “backdrop” of United States v. Texas isn’t unique, and “what’s going on here” is going on a lot. The Justices can’t change the division of business rules in the lower federal courts by themselves. But they could go a long way toward impelling the lower courts (and, failing them, Congress) to limit judge shopping by acknowledging the myriad ways in which the practice disrupts fundamental notions of fairness in our legal system, with implications not just for the technical appropriateness (or lack thereof) of venue in specific divisions of federal district courts in specific cases, but for public faith in the impartiality of the federal judiciary writ large.

SCOTUS Trivia: The Court Sitting Outside the Court

For its first 145 years of existence, the Supreme Court lacked a permanent home of its own. During the brief period in which New York served as the nation’s capital, the Court met on the second floor of the Royal Exchange building. It then moved between two different temporary homes while the federal government was headquartered in Philadelphia (Independence Hall and City Hall). In Washington, the Justices held Court in a series of different quarters in the unfinished Capitol (and, at one point during the War of 1812, a private home), before finally settling in 1860 into what’s now known as the Old Senate Chamber—where they would remain until the Supreme Court Building opened in 1935.

There’s a lot more to say about the Supreme Court Building, including William Howard Taft’s vision for it first as President and later as Chief Justice, and the architectural choices and decisions it embodies. For now, the relevant trivia is that, in the 88 years since the Court’s permanent headquarters opened, there appears to be only one instance in which the full Court (as opposed to individual Justices acting “in chambers”) held formal argument sessions away from it: The October 2001 anthrax scare, during which the Court was one of several federal institutions to receive anthrax-laced envelopes through the U.S. Mail. When the presence of anthrax was confirmed on Friday, October 26, the Supreme Court building was closed for decontamination—even though the Court was scheduled to begin its November argument session the following Monday.

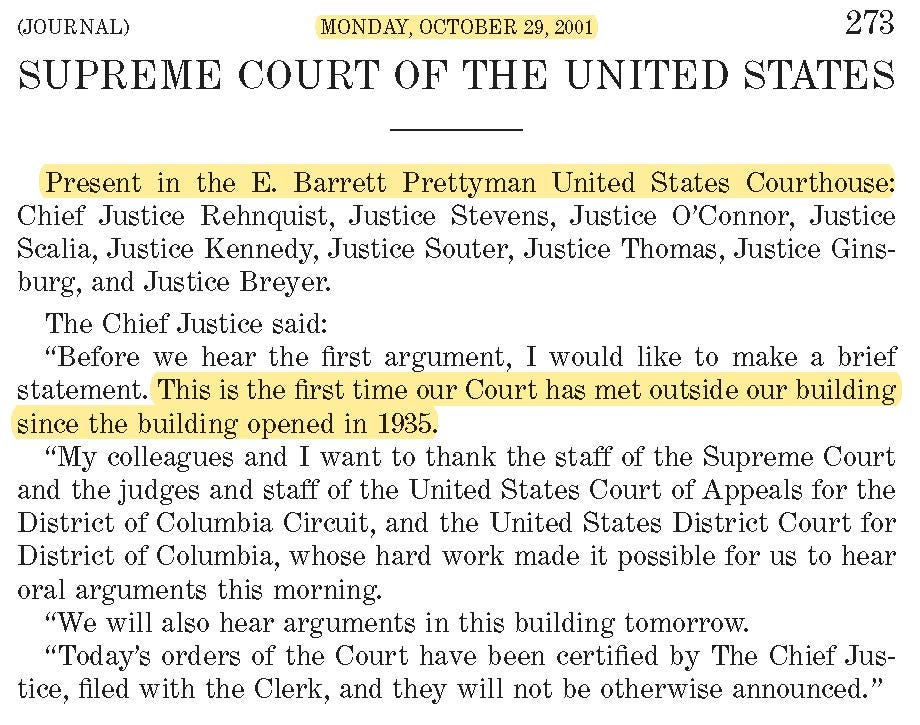

Instead, on Monday, October 29, 2001, the Justices heard oral argument a few blocks away in the E. Barrett Prettyman U.S. Courthouse—home of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit (and the D.C. federal district court). As Chief Justice Rehnquist noted at the beginning of that unusual session, “This is the first time our Court has met outside our building since the building opened in 1935.”

In all, the Court would hear three days of oral arguments at the D.C. Circuit during that last week of October 2001, totaling six cases. By the following Monday, November 5, the Justices were back on the bench at the Supreme Court—the anthrax scare (and their brief trip up Pennsylvania Avenue) behind them.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning at 8 ET.

Happy Monday, everyone! I hope you have a great week.

These are so great! Please keep posting!

Great article. Have you taken a stab at drafting possible legislation that would correct and prevent/prohibit this problem?