15. The Prize Cases and the "Dual Theory" of the Civil War

In upholding President Lincoln's blockade of Confederate ports, the Supreme Court in March 1863 sustained his "dual theory" of the Civil War. But only by a 5-4 vote.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning (even on federal-but-not-University-of-Texas holidays like today), I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it. And if you’re not already subscribed, there’s no time like the present:

On the Docket

The Justices concluded their unofficial mid-winter recess last week without issuing any orders, even though the federal government had asked the Court to grant and expedite a cert. petition challenging a sweeping (and unprecedented) Fifth Circuit decision that effectively invalidates much of the work of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). That grant could still come as early as tomorrow at 9:30 EST, when we expect a full slew of orders (mostly denials of certiorari) out of Friday’s Conference. As John Elwood notes over at SCOTUSblog, there were 423 petitions and motions formally on the Justices’ plate last Friday—reflecting the typical build-up during the month-long January/February break.

The only news to come out of the Court last week was the amended calendar for the February argument session (which starts tomorrow with the first of the two Section 230 cases, about which I wrote in detail last week). The amendment was to remove the “Title 42” case from the calendar, almost certainly in response to a suggestion from the Biden administration that the dispute will become moot on May 11—when the public health emergency on which the COVID-based immigration policy is predicated will expire. To be clear, the Court has not dismissed the case; it is merely sitting on it for now, presumably waiting to see if anything else happens between now and May 11. As a result, the February argument session now includes only six cases, even though, even without adding afternoon arguments, there was room enough for 10. (This continues the pattern of the Court not filling its docket, at least by pre-2019 standards.)

The One First Long Read: The Prize Cases (1863)

In (very loose) honor of Presidents’ Day (a holiday that, IMHO, should be two separate holidays—one for Washington and one for Lincoln), I thought I’d use this week’s issue to write about one of the most fascinating and quietly important Supreme Court decisions during wartime—which had the effect of ratifying one of Lincoln’s most important legal arguments about the Civil War, and, in the process, of openly endorsing the idea that Article II of the Constitution gives the President at least some “inherent” constitutional war powers.

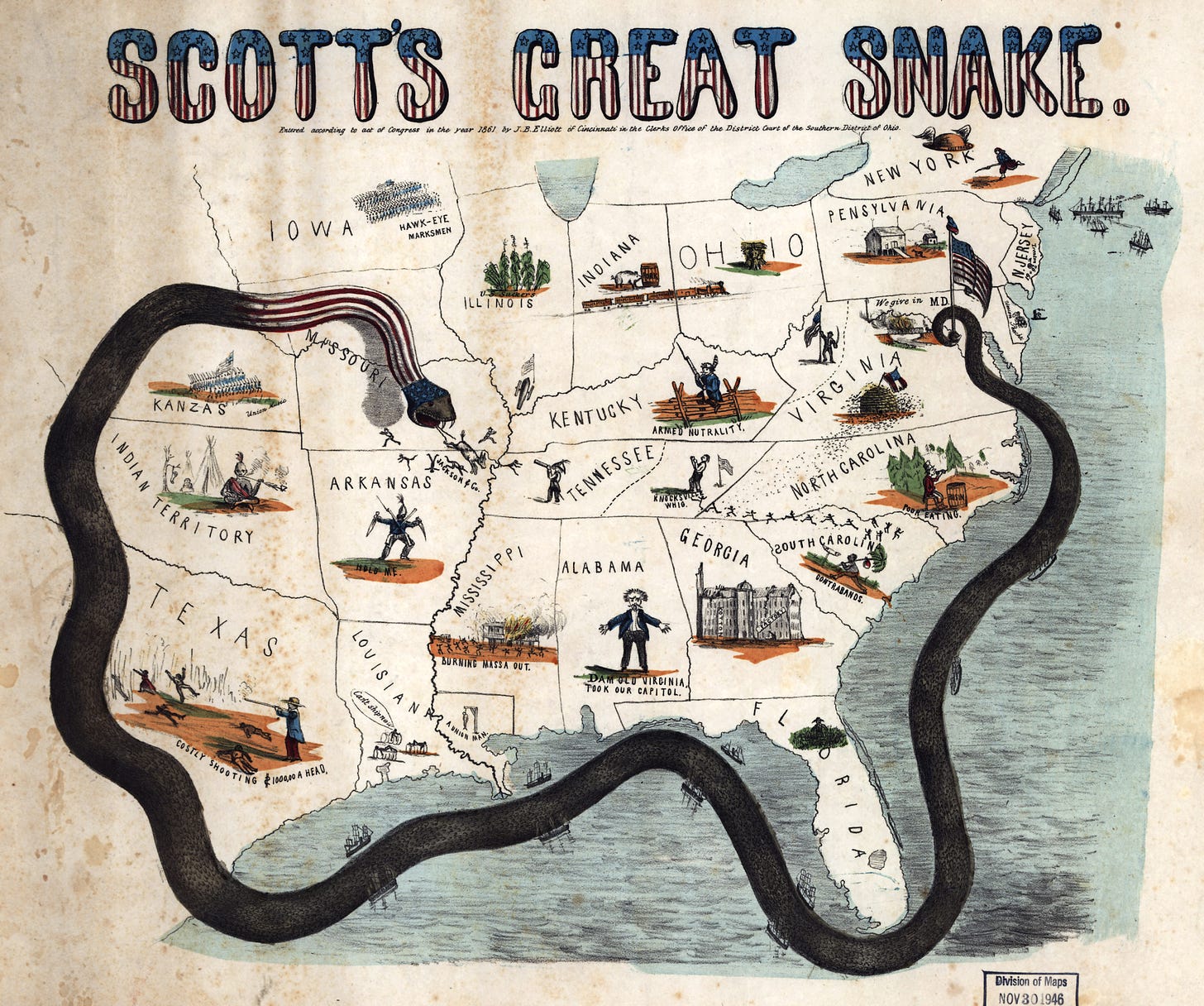

The Court’s 1863 decision in what’s known as The Prize Cases involved four different maritime disputes, all of which arose out of the blockade that President Lincoln unilaterally imposed upon the Confederacy on April 19, 1861—just six days after Fort Sumter surrendered (Congress was out of session, and would not return until July 4, the date on which Lincoln had called them back.) The blockade was a central strategic plank of Winfield Scott’s “Anaconda Plan”—the idea that the Union would use its superior resources, manpower, and geography to strangle the Confederacy into submission by, among other things, denying it the opportunity to trade cotton and tobacco with European powers for the goods and materiel it needed and could no longer obtain from the North.

There were two massive problems with the blockade, though—one practical, and one legal. The practical problem was that, as Roger Lowenstein notes in his great recent book about the financing of the Civil War, “the small Union navy could scarcely patrol thirty-five hundred miles of southern coastline.” (Think Rhett Butler and the real-world blockade runners on whom his character was based.) In the early months of the war, the Union (or privately owned vessels staffed by Union seamen)1 interdicted only roughly one out of every ten ships heading for a Confederate port. But as the war went on, the blockade became much more effective—as the Union captured more territory (especially Confederate ports); as the Navy gained more ships; and as its tactics became more sophisticated. By the summer of 1863, that ratio had increased to stopping one out of every four ships, which made blockade-running increasingly unprofitable (if not dangerous). The blockade was never fully successful, but its economic impact on the war, especially in its later stages, is undeniable.

The legal problem was that countries don’t blockade themselves. Throughout the war, but especially in its early moments, Lincoln walked a razor-thin tightrope when it came to the legal status of the conflict. On one hand, he wanted to afford Confederate soldiers the full rights of belligerents (as opposed to traitors and insurrectionists), at least in part to increase the pressure on the Confederate military to show similar quarter to captured Union troops, and in part to reflect his broader goals of reconciliation once the war was over. But on the other hand, he desperately sought to avoid recognizing the legality of secession, the legitimacy of the Confederate government, or the other implications of treating the opposing forces as part of a sovereign nation-state. More than that, Lincoln was also worried, for much of the war, about the prospect that Great Britain and other European powers might formally recognize the Confederacy—and thus sought to avoid any actions or arguments that might even implicitly facilitate such a step.

This led to what the historian James Garfield Randall, writing in 1926, dubbed the “dual theory” of the Civil War: That the Confederacy was a traitorous insurrection against the lawful authority of the United States, but that its individual soldiers were lawful combatants subject to the protections typically afforded belligerents in international armed conflicts. The decision in The Prize Cases was the closest the Supreme Court came to passing upon the dual theory, and it was a remarkably close call.

In a nutshell, the dispute arose from the capture of four different ships early in the life of the blockade in Spring 1861. The first case to reach the Court involved the Brilliante, a Mexican merchant schooner first detained outside of New Orleans in early June, and then captured outside of Biloxi later that month (from there, it was taken to Key West, where it was subjected to a maritime condemnation proceeding in the Southern District of Florida). The second case involved the Crenshaw, which was owned by Richmond merchants and was captured off of Newport News on May 17, from where it was taken to New York and condemned as prize. The third case involved the Hiawatha, a ship and cargo owned by British subjects that was captured on May 20, 1861 in Hampton Roads and also taken to New York for condemnation proceedings. And the fourth ship, the Brig Amy Warwick, like the Crenshaw, also involved a ship and property owned by Confederates. This one, though, was captured on the high seas (on July 10, 1861, after which it was taken to Boston for condemnation proceedings). All four cases raised the lawfulness of the blockade, but each had a bit of a twist: As Robert Bruce Murray wrote in Legal Cases of the Civil War,

The Brilliante posed the question of the status of a neutral vessel and cargo attempting to run the blockade; the Crenshaw, the status of a vessel and cargo, or most of the cargo, owned by residents of the Confederacy; the Hiawatha, a vessel and cargo owned by a neutral where the violation of the blockade was claimed to be unintentional; and the Amy Warwick, a vessel and cargo owned by residents of the Confederacy but captured on the high seas.

Adding to the stakes, the Lincoln administration feared the specter of having the cases decided by a Supreme Court still controlled by the pro-slavery majority that had decided Dred Scott just a few years earlier (a majority that was believed, not entirely unfairly, to be at least somewhat sympathetic to the Confederate cause). Fortunately for the government, by the time the cases worked their way to Court in late 1862, Lincoln had succeeded in placing three Justices on the bench—Ohioan Noah Swayne; Iowan Samuel Freeman Miller, and Illinoisan (and Lincoln’s close friend) David Davis. All three would side with the Lincoln administration in what would be a 5-4 ruling.

Bespeaking their contemporaneous significance and complexity, the cases were argued across 12 days over the course of three weeks in February 1863 (160 years ago this week). On March 10 (the last day of the December 1862 Term), the Court handed down its long, complicated decision. In a nutshell, the Court sustained Lincoln’s authority to impose the blockade, and largely endorsed the dual theory of the war. Writing for the majority, Justice Robert Grier upheld all four captures, holding that President Lincoln had the legal authority to impose the blockade even without express statutory authorization.

Grier’s opinion, which is not exactly a model of analytical clarity or organization, relied upon two different arguments for the source of Lincoln’s legal authority to impose the blockade. In a passage that is regularly cited by defenders of inherent executive constitutional power, Grier highlighted the President’s constitutional duty (and not just his power) to respond to attacks against the United States (as Fort Sumter clearly was): “If a war be made by invasion of a foreign nation, the President is not only authorized but bound to resist force by force. He does not initiate the war, but is bound to accept the challenge without waiting for any special legislative authority. And whether the hostile party be a foreign invader, or States organized in rebellion, it is none the less a war, although the declaration of it be ‘unilateral.’”

Thus, Grier explained:

Whether the President in fulfilling his duties, as Commander-in-chief, in suppressing an insurrection, has met with such armed hostile resistance, and a civil war of such alarming proportions as will compel him to accord to them the character of belligerents, is a question to be decided by him, and this Court must be governed by the decisions and acts of the political department of the Government to which this power was entrusted. ‘He must determine what degree of force the crisis demands.’ The proclamation of blockade is itself official and conclusive evidence to the Court that a state of war existed which demanded and authorized a recourse to such a measure, under the circumstances peculiar to the case.

But if President Lincoln needed statutory authority for the blockade, Grier also found it in, among other things, the statutes Congress had enacted in 1792, 1795, and 1807 providing for the calling forth of the militia (and, later, the regular armed forces) to “suppress insurrections.” (These statutes, and their contemporary significance, were the subject of my student note in law school.)

Significant scholarly debate remains today about just how distinct the constitutional and statutory holdings were (and whether they were alternative holdings or logically connected ones). But the larger point, on which all agree, is that Grier emphatically embraced the dual theory of the war:

The law of nations is also called the law of nature; it is founded on the common consent as well as the common sense of the world. It contains no such anomalous doctrine as that which this Court are now for the first time desired to pronounce, to wit: That insurgents who have risen in rebellion against their sovereign, expelled her Courts, established a revolutionary government, organized armies, and commenced hostilities, are not enemies because they are traitors; and a war levied on the Government by traitors, in order to dismember and destroy it, is not a war because it is an ‘insurrection.’

In other words, the blockade was legal even though the legal status of the conflict between the Union and the Confederacy was an insurrection, not a “war.” Thus, Grier, joined by the three recent Lincoln appointees and Justice James Moore Wayne, threaded the critical needle between upholding the blockade and not endorsing the sovereignty, in any meaningful respect, of the Confederacy.

It was on this last point that Justice Samuel Nelson focused his dissent, which was joined at least in part by Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney and Justices John Catron and Nathan Clifford. From Nelson’s perspective, a blockade was only lawful under the law of nations during a war between two nation-states. And because no such war had been formally declared at the time of the four captures, he voted to void all four of them. In Nelson’s view, the only way to authorize the blockade would be for Congress to formally declare war against the Confederacy—a move that would’ve run headlong into Lincoln’s efforts to avoid any kind of formal acknowledgment of the legality of secession or Confederate sovereignty.

Nelson lost, but it was remarkably close. And coming as it did in March 1863, more than three months before the Battle of Gettysburg and the fall of Vicksburg, it is fascinating to wonder how the course of the Civil War (and American history) might have changed if one of the five Justices in the majority had voted the other way.

Happy Presidents’ Day!!

SCOTUS Trivia: Circuit Justice or Chief Justice, In Chambers?

Speaking of the Supreme Court and the Civil War, in the battle for nerdiest debate among Federal Courts scholars, the dispute over the specific capacity in which Chief Justice Taney decided Ex parte Merryman has to be up there.

To make a long story short(er), Merryman was a former Maryland legislator and Confederate sympathizer accused of being part of an organized plot to prevent Union troops from being sent through Baltimore to reinforce Washington in late April 1861. Among other things, Merryman was believed to have been involved in burning railroad bridges and other property destruction after the “Pratt Street Riot” on April 19. Indeed, it was the unrest in Maryland that led President Lincoln to first authorize General Scott to suspend the writ of habeas corpus along the “military line between Philadelphia and Annapolis.” When Merryman was arrested by federal troops and sent to Fort McHenry for detention, his father (who just happened to have been Taney’s college roommate) promptly asked the Chief Justice, no friend of Lincoln’s, for a writ of habeas corpus. (The whole story of the Merryman case is a remarkable one, and I’ll try to tell it in a future issue.)

The hard (but ultimately immaterial) question is in which specific capacity Taney received the senior Merryman’s prayer. Ever since 1789, each Justice has had the capacity, on their own, to issue writs of habeas corpus in appropriate cases under section 14 of the Judiciary Act of 1789 (present-day 28 U.S.C. § 2241(a)). But Taney was also the “Circuit Justice” for the District of Maryland, in which capacity he also had statutory authority (under section 14) to issue habeas relief. In other words, was Taney acting as Circuit Justice for the District of Maryland when he issued the writ (only to have it ignored by the Union troops in command of Fort McHenry), or was he acting as the Chief Justice, in chambers?

Most citations to, and discussions of, Merryman assume that Taney was acting as Circuit Justice for the District of Maryland. I’ll confess to thinking that this is the better of the argument—but only for constitutional reasons. The writ the senior Merryman sought was not invoking the Supreme Court’s appellate jurisdiction; it was seeking original relief in a case in which no prior court had issued any ruling. And, as first-year Constitutional Law students learn, the actual holding of Marbury v. Madison is that Congress lacks the constitutional authority to give the Supreme Court original jurisdiction over any case other than those in which a state is a party and those “affecting ambassadors.” Thus, insofar as the prayer was directed to Taney in his capacity as Chief Justice, there’s at least some argument that Taney would have lacked the constitutional authority to issue a writ of habeas corpus.2 But circuit courts faced no such constraints.

To be clear, nothing at all turns on this debate (except the correct Bluebook citation form for Taney’s published opinion in Ex parte Merryman). But it’s a reminder, among other things, of how much more common it used to be for individual Justices to hand down significant rulings all by themselves—whether in their capacity as a Circuit Justice or by exercising statutory authority, like that conferred by section 14 of the Judiciary Act of 1789, that specifically authorized them to act individually and in chambers.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning at 8 ET.

Happy Monday, everyone! I hope you have a great week.

Thanks to Professor J.P. Jones for clarifying this point. (An earlier version of the post had incorrectly referred to the private vessels as privateers.)

Dan Gonen, among others, has argued that Marbury’s limits on the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court don’t apply to individual Justices acting in chambers. I’m more persuaded by the other view, lest an application to an individual Justice be used to bootstrap the full Court’s “appellate” jurisdiction.

Professor Steve -- I had a question that may be more suitable for longer treatment in a future installment: Whatever happened to all the "Cases" cases? In addition to The Prize Cases, there is The Civil Rights Cases, The Slaughter-house Cases, and several others. Why did some cases get this group moniker and some didn't? Why did it apply to some cases that were decided together (Prize) and some that weren't (Insular)? Did they get this group name later on, when they achieved "landmark" status and were highly cited, or were they known by the group name from the start? What would the name of The Prize Cases have been if it had been argued and decided under the name of the lead case, like Brown v. Board of Education was? Why weren't those consolidated cases called The Desegregation Cases or something? Wouldn't The Marriage Cases be easier to remember than Obergefell v. Hodges? When and why did the Court (or lawyers and scholars) stop using these group titles? Thanks for letting me digress into nerdery!