144. The Supreme Court's Late-Night Alien Enemy Act Intervention

Just before 1:00 a.m., the justices (aggressively) stepped back into the Alien Enemy Act litigation—in a decision suggesting that a majority understands that these are no longer normal circumstances.

Welcome back to “One First,” an (increasingly frequent) newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us. If you’re not already a subscriber, I hope you’ll consider becoming one (and, if you already are, upgrading upgrading to a paid subscription if your circumstances permit):

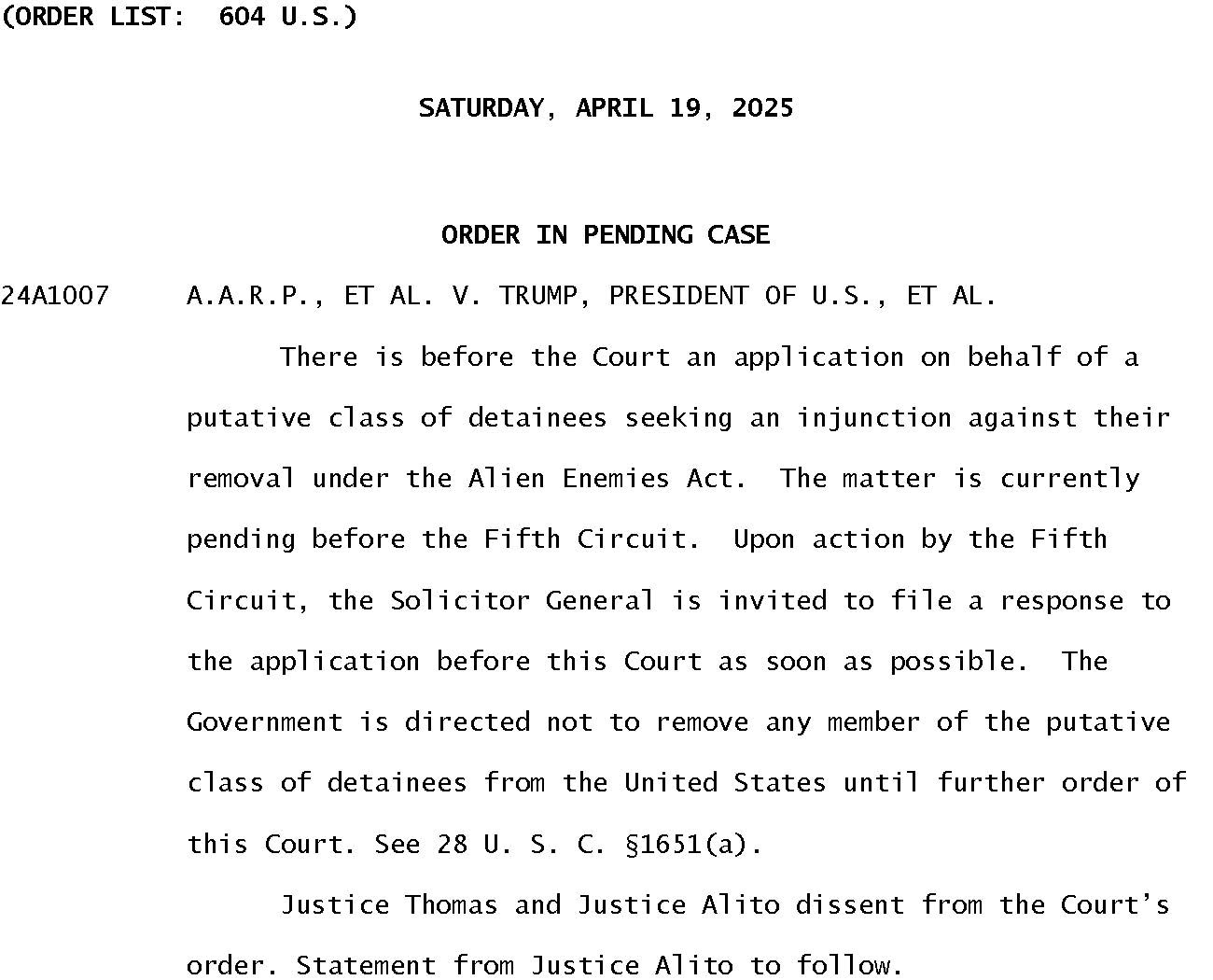

Just before 1:00 a.m. (ET) last night/very early this morning, the Supreme Court handed down a truly remarkable order in the latest litigation challenging the Trump administration’s attempts to use the Alien Enemy Act (AEA) to summarily remove large numbers of non-citizens to third countries, including El Salvador:

I wanted to write a short1 post to try to put the order into at least a little bit of context—and to sketch out just how big a deal I think this (aggressive but tentative) intervention really is.

I. The J.G.G. Ruling

As folks may recall, just 12 days ago, the Court issued a short per curiam opinion in Trump v. J.G.G., in which it held two things: First, a 5-4 majority held that challenges to removal under the AEA must be brought through habeas petitions where detainees are being held, not through Administrative Procedure Act claims in the D.C. district court (like J.G.G.). Second, the Court unanimously held that “AEA detainees must receive notice after the date of this order that they are subject to removal under the Act. The notice must be afforded within a reasonable time and in such a manner as will allow them to actually seek habeas relief in the proper venue before such removal occurs.”

As I wrote at the time, although I disagreed with the majority’s “habeas-only” analysis, the broader ruling made would’ve made at least a modicum of sense if the Court was dealing with any other administration, but it raised at least the possibility that the Trump administration, specifically, would try to play games to make habeas review effectively inadequate. And all of those games would unfold while no court has ruled, one way or the other, on either the facial legal question (does the AEA apply at all to Tren de Aragua); or case-specific factual/legal questions about whether individual detainees really are “members” of TdA. Lo and behold, that’s what happened.

II. The J.A.V. Ruling

In the immediate aftermath of the Court’s April 7 ruling in J.G.G., litigants successfully obtained TROs against AEA removals in three different district courts—the Southern District of New York; the District of Colorado; and, as most relevant here, the Southern District of Texas. In the S.D. Tex. case (J.A.V. v. Trump), Judge Fernando Rodriguez (not that it should matter, but a Trump appointee) barred the government from removing the named plaintiffs or anyone else “that Respondents claim are subject to removal under the [AEA] Proclamation, from the El Valle Detention Center.” (The other rulings were also geographically specific.)

III. The A.A.R.P. Case

Then things got messy. According to media reports, starting on Thursday, a number of non-citizens being held at the Bluebonnet detention facility in Anson, Texas (in the Northern District of Texas) were given notices of their imminent removal under the AEA (in English only), with no guidance as to how they could challenge their removal in advance. Not only did this appear to be in direct contravention of the Supreme Court’s ruling in J.G.G., but it also raised the question of whether the government was moving detainees to Bluebonnet, specifically, to get around the district court orders barring removals of individuals being held at El Valle and other facilities.

The ACLU had already filed a habeas petition on Wednesday in the Northern District of Texas on behalf of two specific (anonymous) plaintiffs and a putative class of all Bluebonnet detainees—captioned A.A.R.P. v. Trump. Judge Hendrix had already denied the ACLU’s initial motion for a TRO—based on government representations that the named plaintiffs were not in imminent threat of removal (he reserved ruling on the request for class-wide relief).

Thus, once the news of the potentially imminent AEA removals started leaking out, the ACLU did two things at once: It sought renewed emergency relief from Judge Hendrix in the A.A.R.P. case, and it went back to Chief Judge Boasberg in the J.G.G. case—which has not yet been dismissed—since that case at least for the moment includes a nationwide class of individuals subject to possible removal under the AEA. And while it waited for both district judges to rule, the ACLU sought emergency relief in A.A.R.P. from both the Fifth Circuit and the Supreme Court.

Sometime after 7 p.m. ET on Friday, Chief Judge Boasberg declined to issue a TRO in J.G.G., concluding from the bench (in my view, correctly) that he couldn’t do so in light of the Supreme Court’s ruling in his case, specifically. Meanwhile, Judge Hendrix issued a brief opinion noting that, although he had been trying to move quickly on the ACLU’s renewed emergency motion, the fact that the ACLU had already gone up to the Fifth Circuit and the Supreme Court deprived him of jurisdiction to do anything further. (I’m not sure that’s true since those were requests for emergency relief, not plenary appeals, but c’est la vie.)

Thus, when many of us (myself included) went to bed last night, there was no specific order blocking removal of the Bluebonnet detainees, even though there were serious reasons to believe that the government was about to effectuate their removal without the notice and process the Supreme Court had required. Indeed, although Chief Judge Boasberg had denied emergency relief in J.G.G., the representations made by the Justice Department lawyer in the hearing Boasberg conducted were … squirrelly, at best.

Then, a little before 1:00 a.m., the Supreme Court stepped in. As noted above, the cryptic order specifies that “The Government is directed not to remove any member of the putative class of detainees from the United States until further order of this Court.” And it notes that (1) the government can respond to the emergency application once the Fifth Circuit rules (which it did even later in the evening—denying emergency relief); and (2) Justices Thomas and Alito dissented, with an opinion from Alito apparently forthcoming.

IV. Taking Stock

Obviously, there’s still a lot we don’t know. But at least initially, this strikes me as a massively important—and revealing—intervention by the Supreme Court, for at least three reasons:

First, the full Court didn’t wait for the Fifth Circuit—or act through the individual Circuit Justice (Justice Alito).2 Even in other fast-moving emergency applications, the Court has often made a show out of at least appearing to wait for the lower courts to rule before intervening—even if that ruling might not have influenced the outcome. Here, though, the Court didn’t wait at all; indeed, the order specifically invites the government to respond once the Fifth Circuit weighed in—acknowledging that the Fifth Circuit hadn’t ruled (and, indeed, that the government hadn’t responded to the application in the Supreme Court) yet. This may seem like a technical point, but it underscores how seriously the Court, or at least a majority of it, took the urgency of the matter. (More on that in a moment.)

Second, the Court didn’t hide behind any procedural technicalities. One of the real themes of the Court’s interventions in Trump-related emergency applications to date has been using procedural technicalities to justify siding with the federal government—including in J.G.G. itself (the first AEA ruling). One could’ve imagined similar procedural objections to such a speedy intervention, on a class-wide basis, in last night’s ruling. (Indeed, I suspect some of those objections are forthcoming in Justice Alito’s impending dissenting opinion.) Here, though, the Court jumped right to the substantive relief the applicants sought—again, reinforcing not just the urgency of the issue, but its gravity.

Third, and perhaps most significantly, the Court seemed to not be content with relying upon representations by the government’s lawyers. In the hearing before Chief Judge Boasberg, Drew Ensign had specifically stated, on behalf of the government, that “no planes” would be leaving Friday, albeit with a bit less clarity about Saturday. True, the government hasn’t formally responded in the Supreme Court, but the justices (or at least their clerks) would have been well aware of the exchange—indeed, some of the clerks were likely listening to the hearing as it happened. In a world in which a majority of the justices were willing to take these kinds of representations at face value, there might’ve been no need to intervene overnight Friday evening; the justices could’ve taken at least some of Saturday to try to sort things out before handing down their decision.

But this case arose only because of the Trump administration’s attempt to play Calvinball with detainees it’s seeking to remove under the Alien Enemy Act. The Court appears to be finally getting the message—and, in turn, handing down rulings with none of the wiggle room we saw in the J.G.G. and Abrego Garcia decisions last week. That’s a massively significant development unto itself—especially if it turns out to be more than a one-off.

V. Now What?

This leads to two final points—one about what happens next, and one about what should happen next.

Starting with the former, last night’s ruling was decidedly temporary—and specifically contemplates further action from the full Court. Presumably, the government will file a response to the application at some point, and the ACLU will reply. On the merits, the ACLU certainly seems to have an awfully strong case—since all it is arguing for is a right for all members of the class to receive the very process that the Supreme Court already required in J.G.G. Perhaps this particular application culminates in a ruling from the justices that is even more specific about the process that J.G.G. requires (including whether the notice must be in Spanish; how long in advance it must be provided; whether it must provide recipients with details on how to challenge their removal; etc.). Again, that wouldn’t have been necessary during any other administration, but it’s increasingly urgent here.

But then there are the “merits” questions. We’re going through all of this rigmarole because no court has yet to rule on whether the government even has the power to use the Alien Enemy Act this way in the first place. As folks know, I think there are very strong arguments that it doesn’t—and a court so holding would provide a substantive impediment to any of the procedural games the government is trying to play. In that sense, it seems a little weird that we’re going through all of this effort to require process before the government can use a substantive authority it probably doesn’t have. Maybe the reason the justices are focusing on the procedures is because they’re not sure what they think of the merits. But the sooner the merits are resolved, it seems to me, the better.

***

There will surely be more to say about both last night’s ruling and the broader litigation context in which it arose, perhaps as early as Monday’s regular newsletter. For now, though, the A.A.R.P. intervention strikes me as a remarkably positive development from the Supreme Court—and a sign that a majority of the justices have lost their patience with the procedural games being played by the Trump administration, at least in the Alien Enemy Act context. Whether that mindset extends to other litigation contexts remains to be seen.

Have a great weekend, all—and, for those who celebrate, Happy Easter.

In my defense, it started as a short post.

One fascinating question is whether Justice Alito, as Circuit Justice for the Fifth Circuit, had himself refused to issue some kind of administrative injunction—and his refusal impelled the full Court to act. We may never know, but it seems at least possible that part of what happened last night was a result of internal dynamics within the Court, as well.

Thank you for taking the time on a busy weekend to clarify these crazy times for us!

Thanks for this explanation that I read before I finished my morning coffee. I upgraded to paid because I have a feeling you'll be staying up late to do more of these.