142. Five Questions About Domestic Use of the Military

The federal government's authorities to use the military for domestic law enforcement are old, broad, and vague. They may soon become far more relevant than they've been for quite a long time.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current work, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. We also just launched “First One,” the weekly bonus audio companion to the newsletter for paid subscribers, with the latest episode dropping last night. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

There is, quite obviously, a heck of a lot to talk about—including the continuing fallout from Thursday’s ruling in the Abrego Garcia case, and the Department of Justice’s … foot-dragging … in complying with it (or with Judge Xinis’s directives on remand). Alas, what has already played out and will continue to play out is exactly what I predicted Friday morning—that the government is taking every iota of wiggle room from the Court’s cryptic order and running with it.

But one of the problems when so much is going on is that we may neglect other stories that are also important, but not as immediate. And so I wanted to use today’s “Long Read” to tackle a topic that may soon become a very big deal—the President’s power to use the military for domestic civilian law enforcement. One of President Trump’s January 20 executive orders directed various officials to report back about the propriety of using the Insurrection Act (about which more in a moment) at and along the border. That report is due April 20, i.e., this coming Sunday. And last Friday, President Trump signed an ominous memorandum authorizing the military to take control of a wide swath of federal land along the U.S.-Mexico border (the “Roosevelt Reservation”)—a move that seems designed to allow the military to arrest non-citizens trying to enter the country unlawfully on the ground that they’re trespassing on military property.

For obvious reasons, the President’s power to use the military for domestic law enforcement is a big deal—and has, historically, been a matter of substantial controversy. Indeed, there are lots of good reasons why we have come to reflexively oppose domestic use of the military except when it is absolutely necessary. But there is meaningful daylight between using the military for domestic law enforcement and using the military in ways that are anti-democratic. And as little as this administration can or should be trusted to hew to the historical line, it’s worth at least articulating what that line is in advance of what may well be the first domestic deployment of regular armed forces since 1992.

But first, the (Court-related) news.

On the Docket

It was quite a week at One First Street. Late Monday came the Court’s ruling in the Alien Enemy Act case (Trump v. J.G.G.), which I broke down here. Tuesday morning, the Court gave Trump another narrow win on an emergency application in the OPM/probationary employees case. And Thursday night came the ruling in Abrego Garcia, about which more here. Beyond those three major headlines, there were a handful of others:

The Court denied stays of execution to Michael Tanzi, who was executed by Florida, and Mikal Mahdi, who was executed by South Carolina;

Chief Justice Roberts issued an administrative stay in Trump v. Wilcox—in which Cathy Harris and Gwynne Wilcox are challenging their removals without cause from the Merit Systems Protection Board and the National Labor Relations Board, specifically. The intervention by Roberts means Harris and Wicox go back to being fired—after the en banc D.C. Circuit had reinstated them earlier last week—while the full Court decides whether they should be fired or not while Trump appeals lower-court rulings reinstating them; and

Justice Kavanaugh issued an administrative stay in a non-Trump-related case—putting on hold an Ohio district court ruling that had blocked an Ohio law that gives Ohio’s Secretary of State the power to reject summaries of proposed ballot initiatives unless he concludes that they are “fair and truthful.”

And all of that on top of a regular (if relatively quiet) Order List last Monday.

Turning to this week, it stands to reason that we’ll get some movement out of the Court in both the Wilcox and Ohio cases. Indeed, it wouldn’t surprise me in Wilcox if the Court simply took up the merits of the issue now—granting certiorari “before judgment” in the D.C. Circuit and potentially setting the case for expedited briefing and argument. I can’t imagine that the justices are willing to take a step as significant as overruling Humphrey’s Executor (or not) through the cryptic and truncated process of an emergency application, but I also suspect, especially given Chief Justice Roberts’s intervention last week, that they don’t want to wait, either. Today also marks one full week since briefing was complete on the birthright citizenship applications, so we could get a ruling on those any time, too.

There was no regular Conference last week, so no Order List is expected at 9:30 this morning. The justices currently have a “non-argument” public session scheduled for this Thursday, but there’s no indication (yet) that the Court will hand down rulings in argued cases then. It might, but given everything else that’s going on, it might not. Otherwise, the next time we expect to hear from the Court is next Monday—with an Order List at 9:30 ET followed by the beginning of the April argument calendar at 10:00.

The “One First” Long Read:

Five Questions About Domestic Use of the Military

About a hundred 21 years ago, I wrote my student note in law school on the “Militia Acts”—a series of statutes enacted by early Congresses, and then amended in 1861 and 1871, to delegate to the President domestic emergency authority that the Constitution had given to Congress—“[t]o provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions.” These statutes, which have unhelpfully become known as the “Insurrection Act” (unhelpful because the authority isn’t limited to suppressing insurrections), are one of the President’s most important—and most controversial—domestic emergency powers. And it’s possible President Trump may soon seek to use the Insurrection Act in some immigration-related capacity; indeed, as noted above, one of the January 20 executive orders calls for a report on potential invocations of the statute by next Sunday.

Although the details of any invocation will matter, I thought it would be useful to tee up even a potential invocation of the Insurrection Act with a brief explainer of where the statutes come from, what they do and don’t authorize, and why, historically, domestic use of the military has been so controversial. To make a long story short, any invocation of the Insurrection Act under our current circumstances would be a dangerous move from the Trump administration, but contra some hot takes on the internet, it would not be tantamount to a declaration of martial law.

1: What is the Insurrection Act, and Why is it Controversial?

The Insurrection Act is actually a series of five statutes Congress enacted—in 1792, 1795, 1807, 1861, and 1871. You can find them today in Chapter 13 of Title 10 of the U.S. Code. I walk through the history and debates over the statutes in detail in my 2004 Yale Law Journal student note. But suffice it to say, the Act as it exists today creates three distinct situations in which the President is authorized to “call out” regular federal armed forces on U.S. soil for law enforcement purposes:

at the request of a state governor “whenever there is an insurrection in any State against its government and the President considers it necessary to use the armed forces to suppress the insurrection”;

without a specific state request when the President considers that “unlawful obstructions, combinations, or assemblages, or rebellion against the authority of the United States make it impracticable to enforce the laws of the United States by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings”; or

most problematically, to put down “any insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy, if it—

(1) so hinders the execution of the laws of that State, and of the United States within the State, that any part or class of its people is deprived of a right, privilege, immunity, or protection named in the Constitution and secured by law, and the constituted authorities of that State are unable, fail, or refuse to protect that right, privilege, or immunity, or to give that protection; or

(2) opposes or obstructs the execution of the laws of the United States or impedes the course of justice under those laws.”

This last provision is the most troubling and open-ended grant of authority—because it turns on neither a request from a governor nor an objectively reviewable determination that it has become impracticable to enforce federal law “by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings.” Indeed, it doesn’t turn on an invasion or insurrection, either. Rather, this particular provision leaves much to the President’s discretion, at least initially, if he deems it necessary to use federal troops to ensure execution of the laws (including, for instance, immigration laws).

Against this backdrop, it’s important to note how rarely the Insurrection Act has been invoked, especially in modern times. The U.S. Army Center for Military History has a truly extraordinary (and free!) three-volume history of the domestic use of the military under the Insurrection Act. But what almost jumps off the page is the paucity of uses of the statute since the end of Vietnam. Some of that is a reflection of increased law enforcement capacity at the local and state levels—so that there’s less need for a federal military backstop. But some of it also reflects the political costs of invoking the Insurrection Act; it has become decidedly unpopular for presidents to use the military domestically—so much so that President Bush notably declined to call out troops in response to Hurricane Katrina; the military assistance there was provided by the Louisiana National Guard in its state capacity.1

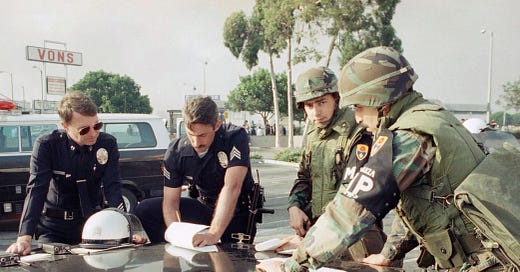

Thus, the last time the Act was used was 33 years ago—when President George H.W. Bush used it to send roughly 4,000 active-duty federal troops into Los Angeles to help restore order after the Rodney King riots. The Insurrection Act has long been a remarkably open-ended delegation of power to the president, but one that presidents have tended to use sparingly and responsibly.

2: Doesn’t the Posse Comitatus Act Bar Domestic Use of the Military?

One common reaction to any discussion of domestic use of the military is to refer to the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878—or, at least, to the principle for which many believe it stands, i.e., that Congress has banned domestic use of the military for civilian law enforcement. That statute, as amended most recently in 2021, provides that:

Whoever, except in cases and under circumstances expressly authorized by the Constitution or Act of Congress, willfully uses any part of the Army, the Navy, the Marine Corps, the Air Force, or the Space Force as a posse comitatus or otherwise to execute the laws shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than two years, or both.

The problem here is the exception for “circumstances expressly authorized by … Act of Congress.” When the Posse Comitatus Act was enacted in 1878, it was understood that it was not meant to override the authority already conferred by the Insurrection Act. Indeed, the Insurrection Act is the most important statutory exception to the PCA. Thus, if the Insurrection Act is validly invoked, then the Posse Comitatus Act is simply inapplicable—and does nothing to limit domestic use of the military for law enforcement purposes. The Posse Comitatus Act isn’t a constitutional constraint; it’s a clear statement rule—and the Insurrection Act, for better or worse, satisfies it.

3: Why Isn’t Invocation of the Insurrection Act Tantamount to Martial Law?

One of the most important—but least understood—points about the Insurrection Act is that it includes no substantive authority. It doesn’t create special powers to arrest or detain people (like the Alien Enemy Act). It doesn’t authorize the military to use force (like declarations of war or the post-9/11 Authorization for the Use of Military Force). Rather, the Insurrection Act is merely an authorization to use federal armed forces to execute the (existing) laws of the Union in circumstances in which no one disputes that those same laws may be enforced by local, state, and even civilian federal authorities. Even when the Insurrection Act has been validly invoked (e.g., Los Angeles in 1992), servicemembers have no powers beyond what ordinary local, state, and federal law enforcement officers have. They can arrest and detain—but only if their civilian counterparts could do so in the same circumstances. The same criminal (and immigration) laws apply; and the same constitutional rights attach, as well. Invoking the Insurrection Act thus isn’t an end-run around legal and constitutional rights; it merely changes against whom those rights can be invoked.

Indeed, this is the whole point of the Insurrection Act’s law-execution function—to use troops to help civilian authorities enforce the laws on the books. So framed, the purpose of the Insurrection Act is to supplement civilian law enforcement, not supplant it. To be sure, there have been circumstances in which martial law was imposed (e.g., during the Civil War and in Hawaii during World War II). But at least historically, that has been understood as a distinct legal question, requiring distinct legal authorization, from simply calling out troops to assist in enforcing federal law. Indeed, the Supreme Court’s admonition in Ex parte Milligan that martial law can’t obtain whenever civilian courts are open and their process is unobstructed only reinforces this distinction.

4: Why, Then, is the Insurrection Act So Controversial?

Notwithstanding this more nuanced understanding of what actually happens when the President invokes the Insurrection Act, it remains highly controversial—in my view, for at least three good reasons.

First, active-duty federal servicemembers really aren’t trained for domestic law enforcement. As Professors Mark Nevitt and John Dehn have explained, federal military personnel are generally trained in standing rules of engagement (SROE), not standing rules for use of force (SRUF). Standing rules for use of force applies to military support to law enforcement, which requires shifting from a more permissive, combat-centric “ROE mindset” to a more constrained, self-defense oriented “RUF mindset.” Soldiers on the Home Front, a wonderful book by two of my casebook co-authors, Professors Steve Dycus and Bill Banks, notes in detail how there can often be (and has often been) a steep learning curve in making this shift. Thus, the risk of error may increase if we come to rely increasingly on active-duty troops, rather than trained civilian personnel, in the domestic law enforcement context. The military in this context is really a broadsword, not a scalpel.

Second, use of the Insurrection Act when governors have not requested assistance reflects a rather stunning usurpation of local and state authority—risking the possibility that we’re turning basic constitutional principles of federalism on their head. It may nevertheless be necessary in circumstances in which local or state authorities are themselves responsible for the non-enforcement of federal law (which is why President Eisenhower rightly used the Insurrection Act to send troops into Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957—to enforce the Supreme Court’s mandate in Brown and desegregate Central High School). But given that the federal government can’t commandeer local and state law enforcement, there’s a serious risk that unjustified invocations of the Insurrection Act would give the federal government power over local and state matters to a degree that the Constitution’s drafters could never have contemplated.

Third, and most importantly, even when the invocation of the Insurrection Act is persuasive on its face, domestic use of the military can nevertheless be corrosive—to the morale of the troops involved, all of a sudden, in policing their own; to the relationship between local/state governments and the federal government; and to the broader relationship between the military and civil society. There are a number of subtle but significant ways in which federal law limits the military’s ability to control civilian functions—including the dual-officeholding ban that I litigated before the Supreme Court in Ortiz v. United States and a host of other statutes, like the one requiring that the Secretary of Defense be a civilian (and one who has been retired for at least seven years). The high historical bar to invocation of the Insurrection Act is of a piece with these other constraints—and with the extent to which the Constitution enshrines civilian control of the military, and not military control of civilians. The Founding-era history that I traced in my old student note reflects that the Constitution’s drafters understood both that (1) there would be extreme circumstances in which the ability to use the military for domestic law enforcement was still worth it; and (2) those circumstances should be carefully circumscribed.

5: What Role Can/Will Courts Play if Trump Invokes These Authorities?

Because invocations of the Insurrection Act historically have been relatively few and far between, and often (if not usually) in circumstances in which the predicates were clearly satisfied, there’s virtually no case law or other judicial precedent respecting the scope of (and limits on) the President’s power under the statute. It stands to reason that individual cases of military arrests and detention (and, should it come to pass, uses of force) will be subject to the same judicial review as the same activities would be if carried out by civilian law enforcement officers. But it also stands to reason that, if President Trump tries to invoke the Insurrection Act in a context in which the factual predicate for doing so is dubious, at best, there will be efforts to challenge the invocation on its face.

It’s really difficult to handicap the odds of such a challenge in advance. A lot will depend upon the specific details of why and how the Act is invoked—and for which purposes. Invoking the Act to send additional troops to the border, for example, may hit a lot differently than doing so to send active-duty military personnel into every American city for the purpose of arresting anyone subject to detention on immigration-related grounds. The devil will very much be in the details. But one thing seems certain: the political checks that historically warded against dubious invocations of the Insurrection Act are not going to stop President Trump from invoking it—perhaps as early as the end of this week. And it will be incumbent upon everyone, if and when that happens, to understand exactly what that does—and doesn’t—mean.

SCOTUS Trivia:

Justice James Wilson and the Whiskey Rebellion

As I noted in my 2004 paper, the very first statute Congress passed to authorize use of the military during a domestic emergency was put to the test by the Whiskey Rebellion—a violent tax-related protest principally in western Pennsylvania that came to a head in August 1794. President George Washington responded to that uprising by following the statute Congress had enacted in 1792 to the letter. Thus, because Washington wanted to call up the militias from Maryland, New Jersey, and Virginia (i.e., from states other than where the emergency had arisen), and because Congress was not in session (the norm at that point in American history), the statute required Washington first to obtain a determination from a federal judge that the factual predicates for calling up out-of-state militias had been satisfied—i.e., that the use of the militias was necessary.

President Washington, headquartered at the time in the Nation’s temporary capital (Philadelphia), turned to Associate Justice (and Pennsylvanian) James Wilson, who also happened to be in Philadelphia at that critical moment. On August 4, 1794, Wilson made the requisite determination. Three days later, Washington issued the dispersal proclamation required by the statute—and, when the protesters did not disperse, sent troops to quell the uprising. Thus, the Supreme Court, or, at least, one of its justices, played a key role in the very first invocation of what we today call the Insurrection Act.

The problem with the Whiskey Rebellion episode is that Congress learned the wrong lessons from it. In 1795, Congress dramatically weakened the checks that had been essential to the passage of the 1792 statute. Among them, it removed the requirement of an antecedent court order—leaving the President as the sole initial arbiter of when circumstances necessitated calling forth the militia (and, after the 1807 Act, the regular armed forces). Washington, after all, had earned Congress’s trust. It’s too bad that Congress didn’t foresee future presidents who’d be … less deserving of it.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone (no later than) next Monday.

National Guard troops wear three hats: They can be in “State Active Duty” status—when they are carrying out state prerogatives at the behest of their Governor. They can be in “federalized” or “Title 10” status—when they have been activated by the President and are serving effectively as federal troops. Or they can be in “Title 32” status—a hybrid in which they remain under state control, but provide support to federal missions (with the consent of their Governor). Back in 2020, I wrote a lengthy post about these distinctions—and how President Trump abused Title 32 status during the first administration. Further abuses are possible now, as well; the key is that they’d depend upon the acquiescence of the states who choose to send troops.

It's tough when the Trump regime does so many things that offend common sense but are actually potentially legally viable. It really points out that the most powerful weapon to stop Trump, the political process, is the one that's failed so spectacularly.

There is a certain head-spinning irony in the report on domestic use of the military being due on Easter Sunday... a Christian celebration of the "Prince of Peace."