14. Section 230, Big Tech, and the Court

Justice Thomas has pushed the Court to consider whether social media platforms have too much power. Neither of the two complex cases the Justices are set to hear next week truly raise that question.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

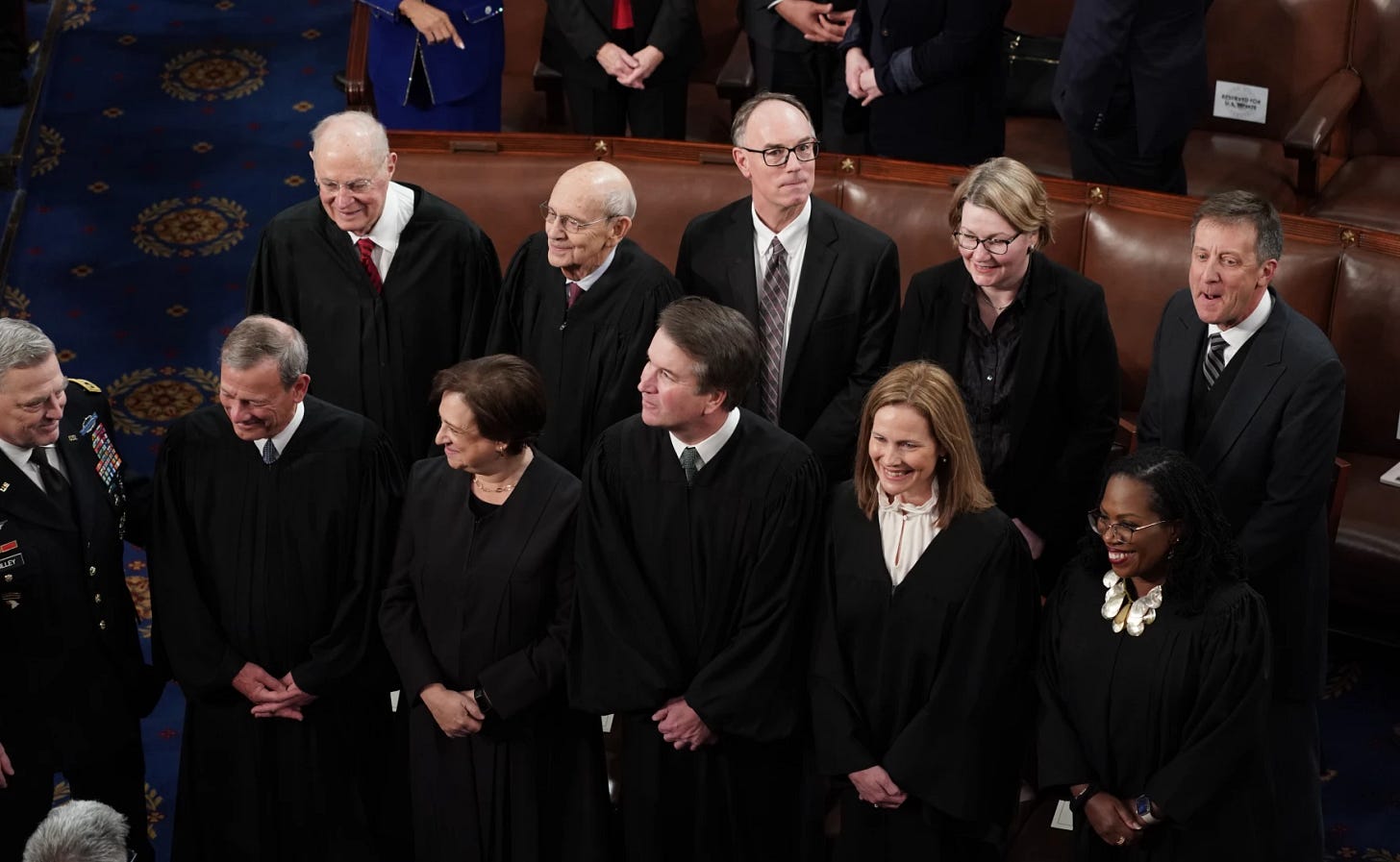

The Justices marked the last full week of their mid-winter recess with only two orders—each of which refused to stay impending executions with no public dissents. (For more on the origins of this pattern and why the dissent-less denials were unsurprising, see the January 16 newsletter.) Otherwise, about the only newsworthy thing involving the Justices last week was the attendance of five current Justices (Roberts, Kagan, Kavanaugh, Barrett, and Jackson) and two retired Justices (Kennedy and Breyer) at President Biden’s State of the Union address. Indeed, it was the first time that a retired Justice attended the State of the Union since Justice White in 1997.

But if you really want to test your SCOTUS knowledge, see if you can name the three officers of the Court standing to Justice Breyer’s left in this picture (see the caption for answers):

The Justices are due to meet in person this Friday for their February 17 Conference. Among the cases the Court has relisted from the January 20 Conference (a potential signal either of certiorari interest or that a Justice may be writing a separate opinion respecting a denial) is the pending petition (on which I’m counsel of record) in Steven Donziger’s appeal of his criminal contempt conviction, which raises separation-of-powers questions about the federal courts’ power to appoint private special prosecutors to try criminal contempt offenses that DOJ declines to prosecute. Orders from the February 17 Conference aren’t expected until next Tuesday at 9:30 a.m. EST.

The One First Long Read: The Section 230 Case(s)

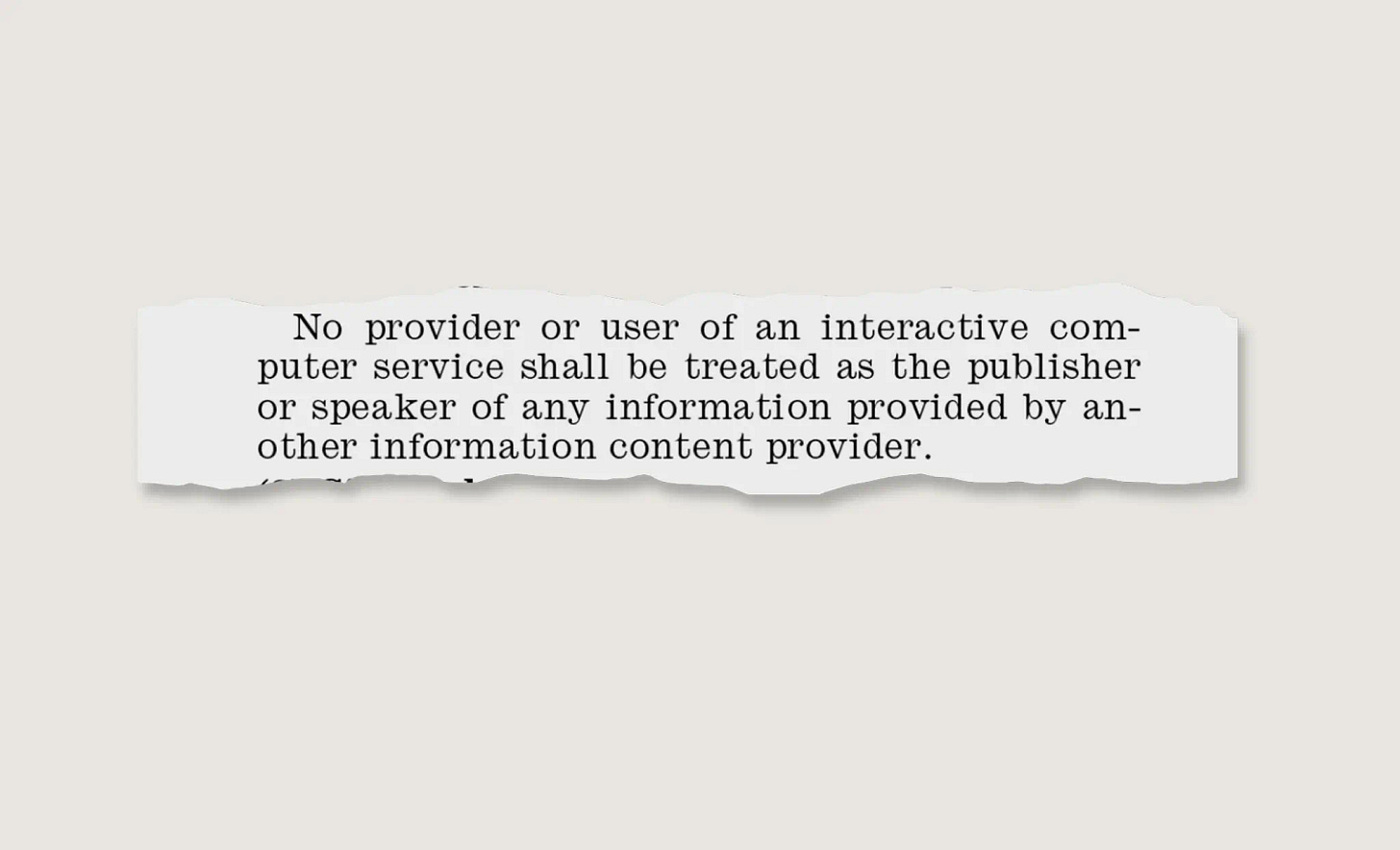

“Section 230,” which was enacted as part of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, has increasingly become a lightning rod for critics of big tech companies in general and their control of social media platforms, in particular. At its core, section 230 generally immunizes “interactive computer service providers” from liability for content generated by third-party users—so that, if I defame someone in a tweet, the subject can sue me, but not Twitter, for my malfeasance. Although prior case law had allowed liability for “publishing” content online as opposed to merely “distributing” it, section 230 moved the line, providing that it does not count as “publishing” to merely provide a forum for someone else’s content:

In the other direction, section 230 also insulates those websites from liability for taking down user content that is “obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable, whether or not such material is constitutionally protected.” There are important exceptions to section 230: It doesn’t insulate platforms from liability for federal crimes; violations of other electronic privacy laws; or intellectual property claims. But it has functioned as a remarkably effective shield over its 27-year history—too effective, in the eyes of some. As Daisuke Wakabayashi wrote for the New York Times in 2019, “Section 230 has allowed the modern internet to flourish. Sites can moderate content—set their own rules for what is and what is not allowed—without being liable for everything posted by visitors.”

Section 230’s breadth has been criticized from both ends of the political spectrum. Progressives have often railed against it for disincentivizing websites from taking down offensive or harassing content, and thereby enabling the amplification of revenge porn and other indecent behavior. And Republicans have often claimed that section 230 makes it easier for platforms like Facebook and Twitter to censor conservatives—since the statute immunizes them from liability for any claimed viewpoint discrimination. Some of these criticisms have led to modest recent reforms, including a 2018 statute that removes section 230 immunity from services that knowingly facilitate or support sex trafficking. But broader reforms have largely stalled in Congress, at least for now.

One of the more visible judicial critics has been Justice Clarence Thomas. In an October 2020 statement respecting a denial of certiorari, Thomas laid out in some detail a series of specific arguments about why, in his view, lower courts had interpreted section 230’s immunity too broadly. And in an April 2021 concurrence in a denial of certiorari, Thomas went further, suggesting that the ability of large social media platforms to cut off speech might raise its own First Amendment concerns—so that section 230 could provoke difficult constitutional questions insofar as it preempts state laws prohibiting private companies from censoring speech.

At the time Thomas wrote those opinions, no state had yet passed such a law. But Florida and Texas have now done so, provoking a direct circuit split between the Fifth and Eleventh Circuits on whether state laws limiting content moderation by social media platforms are themselves constitutional. The Eleventh Circuit said no; the Fifth Circuit said yes, only to have the Supreme Court, by a 5-4 vote, vacate its stay of a district court injunction last May. (More on these cases shortly.)

All of that brings us to the arguments coming up next Tuesday and Wednesday in the first two section 230 cases the Court has ever heard. The cases could have major implications not just for section 230, but for the entire (and mostly unrelated) field of tort litigation arising out of acts of international terrorism. But in important respects, these cases don’t fully raise the debate that Justice Thomas has said that he wants the Court to have. That debate is better raised by, and resolved in, the content moderation cases that are on already on their way.

The two cases the Court is hearing next week come from appeals of three different lawsuits that were decided by the Ninth Circuit in a single ruling. The cases involve suits on behalf of five victims of ISIS or ISIS-inspired terrorist attacks (in Paris, Istanbul, and San Bernardino) against Google, Twitter, and Facebook. All three platforms, the plaintiffs allege, allowed ISIS to post videos and other content to communicate the terrorist group's message, to radicalize new recruits, and to generally further its mission. The victims also claim that Google placed paid advertisements in proximity to ISIS-created content and shared the resulting ad revenue with ISIS. The suits were brought under the Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA), as amended in 2016 by the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act (JASTA), which expressly authorizes broad theories of secondary liability against those who knowingly provide support to international terrorist organizations (more on that shortly, too).

In the Gonzalez appeal, the Ninth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of the plaintiffs’ suit, holding that their claims were generally barred by section 230 because the 1996 statute protects platforms even when their algorithms target specific users and recommend someone else’s content (as the Gonzalez plaintiffs allege with respect to YouTube, which is owned by Google). But in the Taamneh appeal, the Ninth Circuit reversed the dismissal of the plaintiffs’ suit, holding that the plaintiffs had plausibly alleged a claim for aiding-and-abetting liability against the platforms, and so it remanded for further proceedings (the district court had dismissed the suit without reaching whether section 230 barred the plaintiffs’ claims, so the Ninth Circuit didn’t reach that issue either).1

Thus, when the Gonzalez plaintiffs asked the Supreme Court to take up the Ninth Circuit’s section 230 holding, Twitter filed a “conditional” petition for certiorari, asking the Court, if and only if it agreed to take up the section 230 issue in Gonzalez, to also take up the Ninth Circuit’s aiding-and-abetting analysis in Taamneh. Even though the cases don’t turn on each other, the Court agreed, and granted both petitions. But what should already be clear is that only one of the cases (Gonzalez) is really about section 230; Taamneh, at least in the posture in which it has reached the Justices, isn’t about section 230 at all.

As for Gonzalez, the underlying question—whether providers are covered by section 230 when their algorithms target specific users and recommend specific content—has enormous ramifications in both directions for the entire tech industry. That might help to explain why more than 75 amicus briefs have been filed in the case, a majority in support of the tech defendants.

But as significant a question as that is for tech industry, it’s not the question Justice Thomas has been pushing the Court to answer. Thomas’s objections, at least as articulated in his 2020 and 2021 opinions, are about whether section 230 should be understood to immunize specific and intentional content moderation decisions (Justice Alito sounded a similar theme in his dissent from the Court’s May 2022 order vacating the stay in the Texas content moderation case, which Thomas joined). There’s plenty of room to think that one answer should govern when platform operators are making individual decisions about specific posts, but a different answer should govern when the decision is made automatically by the platform’s code. (One might also think that this kind of debate is in any event better resolved by Congress than by the Court, especially given that we’re all interpreting a 27-year-old statute enacted before Google.com even existed, let alone the rise of modern social media networks.)

More fundamentally, whatever its merits, Justice Thomas’s real objection to the behavior of social media platforms is one far more directly implicated by the Florida and Texas cases, where the question isn’t about any context-specific distinction between publishing and distributing content, but rather more broadly about whether large social media platforms should be thought of as akin to “common carriers” whose content moderation can (and should) be regulated by the federal government and/or the states notwithstanding the First Amendment. (The extreme version of this view asks whether some of these platforms ought to be subject to the First Amendment themselves.) On January 23, the Court called for the views of the Solicitor General in the Florida and Texas cases. But that just kicks them down the road to next Term; given the circuit split and the Court’s own prior intervention in the Texas case, a grant of certiorari is virtually inevitable.

In other words, Gonzalez is a massively important case about a specific application of section 230, but it’s not the massively important case about big tech that Justice Thomas has been clamoring for the Justices to take up.

As for Taamneh, let me first make clear my own interest and involvement: I’m counsel of record on an amicus brief in support of the respondents (the plaintiffs) by ATA scholars, which explains in some detail why the Ninth Circuit’s analysis of JASTA is deeply consistent with that statute’s text and context. (Our group of amici have filed a series of similar briefs in JASTA cases in the lower courts.) That said, the real question in Taamneh is one that has been the subject of substantial litigation in the lower courts in suits arising out of transnational terrorist attacks: whether Congress really meant to authorize indirect aiding-and-abetting liability so that companies can be held liable without any specific intent to further the underlying acts of international terrorism, and based solely on evidence that they knew that they were providing “substantial support” to a criminal enterprise. In my view, the statute’s text sure seems to say “yes”; here’s section 2(b):

To that end, JASTA expressly incorporates the test for secondary liability articulated by a remarkable D.C. Circuit panel (Wald, Bork, and Scalia, JJ.) in a 1983 case known as Halberstam v. Welch. Our amicus brief argues that the decision below gets Halberstam right, and that the arguments advanced by Twitter and its amici would undermine the core purpose of JASTA, which was adopted in response to previous judicial decisions narrowly interpreting the ATA, by undercutting the broad secondary liability Halberstam recognizes.

We’ll see if that position has any traction with the Court. But the larger point is that this is an issue that has very little to do with big tech, specifically. Instead, it’s been a recurring matter of debate in suits against banks, pharmaceutical companies, and a host of other large corporations relating to their indirect support of post-September 11 acts of transnational terrorism. Facebook, Twitter, and Google are a small part of that story, but only a small part. Thus, insofar as these cases were meant to be referenda on the power of tech companies, Taamneh certainly isn’t and Gonzalez only is at its margins. Whether that comes out in next week’s argument, and whether it tempers the Justices’ reactions and ultimate rulings in these disputes, remains to be seen.

SCOTUS Trivia: Passing Notes in Class

All of the discussion of social media reminds me of one of my favorite SCOTUS anecdotes—related to the practice (that, by all accounts, continues to this day) of the Justices passing notes to each other in the middle of oral argument, and passing notes from aides/pages with outside news down the bench.

One such note was passed from Justice Potter Stewart to Justice Harry Blackmun, shortly after 1 p.m. on Wednesday, October 10, 1973. The Justices were in the middle of hearing argument in United States v. Richardson, a case about whether a taxpayer had standing to challenge secret (and allegedly unconstitutional) expenditures by the CIA; they’d eventually hold, by a 5-4 vote, that the answer was no. But it was also the decisive Game 5 of the 1973 National League Championship Series, between the Cincinnati Reds and (my) New York Mets. After Ken Griffey (Sr.) flew out with the bases loaded to end the top of the first inning, Stewart passed one note to Blackmun apprising him of the details.

The next note reflected that Ed Kranepool had connected for a two-run single with one out in the bottom of the first to put the Mets up (in a game they’d go on to win, 7-2). But it also relayed some other breaking news:

Instead of noting that the Mets have only won two winner-take-all playoff games since that day in October 1973 (Game 7 of the 1986 World Series and Game 5 of the 2015 National League Division Series), I’ll just note that pitchers and catchers report on Wednesday.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning at 8 ET.

Happy Monday, everyone! I hope you have a great week.

The third appeal, in the Clayborn case, is not before the Supreme Court.

You’ve added a lot of depth to what’s at stake, or not at stake, in the upcoming 230 cases. Certainly helps me, a non-lawyer, understand. Thanks.

Well done, carry on, and stay safe out there.