135. The Trump Reckoning Reaches the Court

How the justices navigate the six pending emergency applications from the Trump administration will tell us a lot about how much (or how little) the Court will be a bulwark against the President.

Welcome back to “One First,” an (increasingly frequent) newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

I wanted to put up a post today (Friday), rather than wait for Monday’s “regular” newsletter, because of the unprecedented flurry of activity we’ve seen from the Trump administration at the Supreme Court—including the filing of three separate emergency applications in the last four days, each of which seeks to put back into effect controversial policies that were blocked by federal district courts, rulings that three different federal courts of appeals kept in place. If we add in the three pending emergency applications in the birthright citizenship cases, that brings the total to six pending applications from the federal government—with a seventh potentially on the way.

This post has two goals. The first is to simply summarize the four different disputes at issue across these six applications—since it’s becoming increasingly difficult to keep the dizzying litigation against Trump (and dizzying pace of lower-court rulings) straight. The second is to suggest, in contrast to the first Trump II case to reach the Court, that these cases are the reckoning we’ve been waiting for. Between them (and, in one case, all by itself), they ought to give us (and the executive branch) a lot more insight into just how much (or just how little) a majority of the Court is willing and able to stand up to President Trump—and, ultimately, for the rule of law.

Hopefully, the justices appreciate that, too.

I. Six Applications and Four Policies

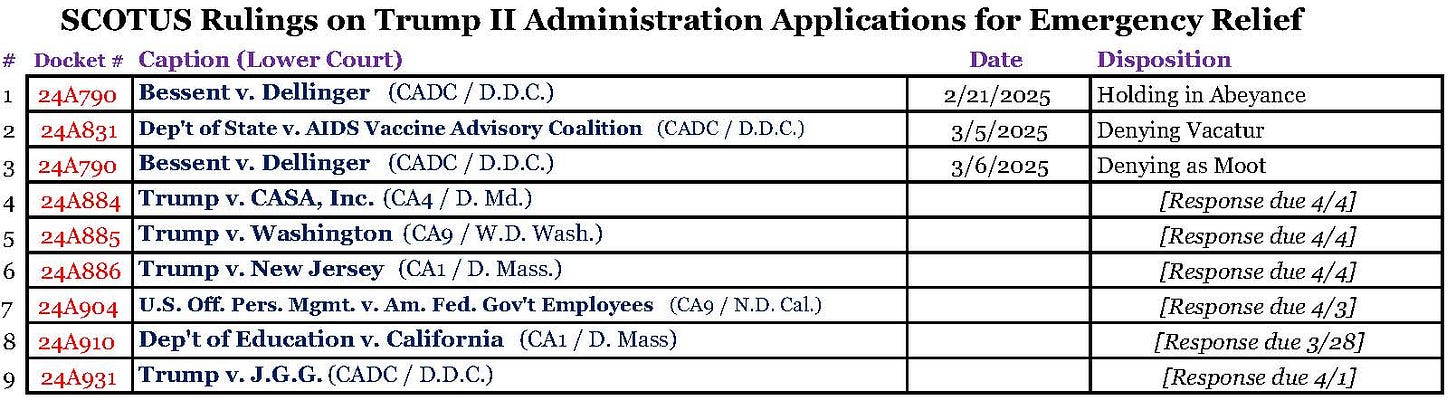

As of this writing, the Trump administration has filed eight emergency applications since coming to office on January 20. (Of note, that’s the same total that the federal government filed during the entirety of the George W. Bush and Obama administrations, i.e., from 2001-17. The first Trump administration ended up filing a total of 41 in four years; the Biden administration filed 19.)

Two of those applications have already been resolved—in the Hampton Dellinger case and the USAID funding cases. It’s hard to call either of those rulings “wins” for the challengers, but they weren’t what the Trump administration asked for, either. That leaves six applications that are pending, which are presented here in the order in which they were filed.

A. The Three Birthright Citizenship Cases

I wrote last week in detail about the first three applications—24A884, 24A885, and 24A886—which all seek to put into effect most (but not all) of President Trump’s efforts to limit birthright citizenship. I won’t rehash my earlier post here, other than to note that the principal focus of these applications is not a defense of the policy, but rather an argument against the “nationwide” scope of the injunctions entered by federal judges in Boston, Greenbelt (Maryland), and Seattle, and left in place by the First, Fourth, and Ninth Circuits. As I wrote last week, these applications are a singularly poor vehicle through which to consider that issue—a fact that might help explain why the Court is slow-walking them. Even though the government filed the applications on March 13 (two weeks ago yesterday), the challengers’ responses aren’t due until next Friday, April 4. That suggests a ruling sometime the week of April 7—and one that, at least going off of these tea leaves, is not likely to go the government’s way.

B. The Mass Firing of Probationary Employees

The fourth pending application, 24A904, is an effort to freeze a ruling by a San Francisco-based federal judge that ordered the federal government to immediately restore more than 16,000 probationary employees who were fired from six agencies in February. The gravamen of Judge Alsup’s ruling was not that the government lacks the power to fire probationary employees, but that the Office of Personnel Management, specifically, lacks that authority.

In its emergency application, filed on Monday (before the Ninth Circuit had ruled on its stay application), the federal government principally argues that the plaintiffs lacked standing to bring this suit; and that any challenges to OPM’s actions have to go through the internal, administrative process provided to government employees through the Merit Systems Protection Board (which Trump is also seeking to restructure). On Wednesday, the Ninth Circuit denied the government’s application by a 2-1 vote, with the majority concluding that the government was unlikely to succeed on its standing or preemption arguments. Judge Bade’s dissent focused entirely on standing.

Justice Kagan, as circuit justice for the Ninth Circuit, apparently waited for the Ninth Circuit to rule before ordering the plaintiffs to respond to the government’s application. That response is now due next Thursday (April 3), by noon EDT. And although the government had also asked the Court (and Justice Kagan) to issue an “administrative stay” temporarily pausing Alsup’s order even while the Court considers its request more broadly, the Court has … not granted that.

C. Department of Education Grants

The fifth pending application, 24A910, is the one that’s received the least attention, but may be the first on which we receive a ruling. Filed on Wednesday, the application seeks to halt a Boston federal judge’s ruling that the Department of Education had unlawfully terminated more than $65 million in training grants meant to address teacher shortages. The government stopped the funds because it claimed they were funding programs that have diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives.

Last Friday, the First Circuit declined to freeze Judge Joun’s ruling, holding that district courts, rather than the Court of Federal Claims, had the power to hear the plaintiffs’ challenges, and that the plaintiffs were likely to succeed on their claims that the Department of Education’s terminations were “arbitrary and capricious” because they were insufficiently explained and defended. The government’s application challenges both of their holdings—and, as in the probationary employees’ case, seeks an immediate “administrative” stay.

Justice Jackson, as circuit justice for the First Circuit, has not acted on the administrative stay request. But she has moved a bit more quickly in ordering a response—with the plaintiffs’ opposition due by 4 p.m. (ET) today. Thus, we may well get a ruling in this case by early next week (if not sooner).

D. The Alien Enemy Act Removals

The most recently filed application, 24A931, is also, in my view, the most important—with the government seeking to clear the way to resume mass, summary removals under the Alien Enemy Act of 1798 of individuals it claims are Venezuelan citizens and members of Tren de Aragua. I’ve written about this litigation before, so won’t belabor the point. But as relevant here, the government is asking the Supreme Court to freeze two different orders from Chief Judge Boasberg—one that temporarily barred the government from removing five specific individuals under the act; and one that temporarily barred the government, on a class-wide basis, from removing anyone else under the act.

On Wednesday, a divided panel of the D.C. Circuit rejected the government’s applications to freeze either of the orders, with all three judges writing separately. Strikingly, Judge Karen Henderson, a George H.W. Bush appointee who is well known for being deferential to the government in national security cases, wrote a (in my view, powerful) 29-page concurrence in support of that outcome (she was joined by Judge Patricia Millett, who wrote a 41-page concurrence of her own).

The government’s application in the Supreme Court picks up from Judge Justin Walker’s dissent in the D.C. Circuit—arguing first that the challengers have to use habeas petitions (filed where they are detained, i.e., in South Texas) to challenge their potential removal under the Alien Enemy Act; and second, that, at the very least, the nationwide nature of Chief Judge Boasberg’s second order is overbroad and should be limited.

Chief Justice Roberts immediately requested a response to the application, but one that isn’t due until next Tuesday (April 1), at 10 ET. Thus, by the end of next week, the Court will have (at least) six fully briefed emergency applications from the federal government covering four major disputes.

II. The Stakes

Shortly after the election last fall, I wrote about how the Supreme Court’s October 2024 Term was going to end up dominated by emergency applications from the second Trump administration seeking to undo lower-court rulings blocking its most controversial (and legally dubious) initiatives. Here we are. It’s not just that these six applications are all before the Court at the same time; it’s that they run much of the gamut of the types of disputes we’re seeing across the lower federal courts right now. There’s a major funding cutoff dispute (Department of Education); there’s major immigration policy disputes (the birthright citizenship cases); there’s a major dispute over mass firings of executive branch employees; and then there’s the Alien Enemy Act case. Far more than the first firing case (which was an outlier in multiple respects), and the first funding case (which had its own case-specific issues), these cases, especially together, reflect the inevitable reckoning—just how much is the Supreme Court going to stand up to Trump?

But at the risk of offering what may be an idiosyncratic observation, it’s not just these cases collectively that have brought us to the moment of truth; it’s the Alien Enemy Act case, specifically. Not only is that case beset with the broader baggage of the ill-conceived attacks on, and calls for impeachment of, Chief Judge Boasberg (and Chief Justice Roberts’s surprisingly quick response), but at its core, that case is as much about fundamental rule-of-law premises as anything we’ve seen in the first two months and eight days of this administration.

With the government continuing to pick random non-citizens up off the streets in alarming circumstances (the video of the Boston arrest of Turkish student Rumeysa Ozturk is chilling), the question of whether the government must provide at least a modicum of legal process before removing individuals from the country, especially those who end up in a Salvadoran prison, cuts to the heart of the rule of law. The technical argument that these claims must be brought through individual habeas petitions is sufficiently tenuous that it would be incredibly cynical for the Supreme Court to use that reasoning as a basis for letting the Trump administration off the hook—even more so than using belated hostility to nationwide injunctions to put the birthright citizenship executive order mostly into effect.

I don’t mean to suggest that the other cases are unimportant; anything but. But there’s something fundamentally different about a dispute over firing government employees or cancelling government grants, on the one hand, and disappearing people off the street without due process, on the other. The reckoning the Court now faces is thus not just about how much it is willing and able to stand up to President Trump, but how committed, at the most basic level, the justices are to standing up for a government of laws, and not of men.

If you’re not already a subscriber, I hope you’ll consider becoming one. And if you’re not a paid subscriber but your circumstances permit, I hope you’ll consider becoming one of those, too. Regardless, we’ll be back Monday with our “regular” issue of the newsletter.

Stay safe out there.

Thank you,Steve, for all your hard work. That video of masked men grabbing someone off the street is horrific. I hope Tufts University fights back.

68 days...I would say everyone should have begun digesting Project 2025 as soon as it hit the internet. The speed, the cruelty, the caving of some in the legal, educational, and media sectors continues to horrify and galvanize citizen pushback. We are in for a very long struggle.