134. The Attempted Assassination of Justice Field

The too-strange-for-fiction story of how Justice Stephen Field was almost assassinated in 1889 and the important Supreme Court presidential power precedent that his bodyguard's actions precipitated.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current work, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. We also just launched “First One,” the weekly bonus audio companion to the newsletter for paid subscribers, with the second episode dropping last night. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

Perhaps the biggest Supreme Court-related news of the past week was Chief Justice John Roberts’s striking statement on Tuesday in response to continuing attacks on (and calls for impeachment of) federal judges who are ruling against President Trump: “For more than two centuries, it has been established that impeachment is not an appropriate response to disagreement concerning a judicial decision. The normal appellate review process exists for that purpose.” I recently wrote about why and how we don’t use the impeachment power simply because of disagreements with a judge’s rulings, and won’t rehash those arguments here. Instead, I thought it would be worth picking up a different piece of this issue—the real-world threats to judges that the increasingly ugly rhetoric from Trump and others are stirring.

It should go without saying that these kinds of threats are profoundly dangerous—not just because of the possibility that those making them aren’t just blustering, but because of the extent to which trying to physically intimidate judges is inconsistent with foundational principles of judicial independence and the rule of law.1 But they also expose a tricky legal point—which is that federal judges, especially lower-court judges, depend almost entirely upon the executive branch for protection from physical harm—usually through the auspices of the U.S. Marshal’s Service (itself an arm of the Department of Justice).2

The origins of that (formal) protection can be traced to a remarkably colorful episode in 1889 involving Justice Stephen Field—which, among other things, helped to establish an important Supreme Court precedent with respect to presidential power. In Field’s case, the issue was whether the President even needed statutory authorization to protect justices and judges from harm (a question that Court answered in the negative, albeit over two dissents!). Flipping it over, Field’s case today raises the question of whether Congress should give lower federal courts more power to protect themselves without depending upon the President’s support—a power the Supreme Court has (quietly) had for some time.

But first, the news.

On the Docket

The biggest news out of the Court last week was unquestionably the Chief Justice’s Tuesday statement. The Chief’s brief missive was almost certainly intended as a direct response to President Trump, who had called, earlier Tuesday, for the impeachment of Chief Judge Boasberg (the highly respected judge presiding over the Alien Enemy Act litigation in the D.C. federal district court). What is striking about the Chief’s statement is less what it says (with which I quite obviously agree), but how quickly he said it. This was a message—not just to the President and his supporters to knock if off, but to lower-court judges that the Chief Justice has their back. I realize that there are many for whom it’s too little, too late (especially given the Chief’s role in last July’s presidential immunity decision). For what it’s worth, I still think it’s a very good thing that he said it, and yet another sign that, unlike some other institutions that ought to know better, the Court is in no hurry to placate the President.

On Friday, the Court handed down two (relatively modest) rulings in argued cases:

Delligatti v. United States: For a 7-2 majority, Justice Thomas held that a second-degree homicide under New York state law counts as a “crime of violence” under the federal Armed Career Criminals Act (and thus triggered a mandatory minimum sentence of at least five years in the defendant’s case). Even if second-degree homicide in New York can be accomplished through omission, it still requires proof that the defendant intentionally caused the victim’s death—thereby satisfying the federal statutory requirement. Justice Gorsuch, joined by Justice Jackson, dissented—arguing that the federal definition, properly understood, excludes any and all crimes of omission.

Thompson v. United States: For a unanimous Court, Chief Justice Roberts held that a federal statute that makes it a crime to “knowingly make any false statement” with respect to a loan or credit application does not extend to knowingly misleading, but not necessarily false, statements—that proof of a statement’s falsity, as such, is essential to a conviction under that provision. Justices Alito and Jackson wrote separate concurring opinions.

The Court also handed down four rulings last week on emergency applications—covering two attempts to block pending executions. On Tuesday, a 5-4 Court refused to block Louisiana’s execution of Jessie Hoffman—over public dissents from the three Democratic appointees and Justice Gorsuch (the latter of whom wrote separately to criticize the Fifth Circuit for failing to consider Hoffman’s objection to his method of execution under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000). And on Thursday, this time with no public dissents, the justices turned away three applications from Florida death-row prisoner Edward James. The Court also handed down two sets of routine housekeeping orders.

Turning to this week, we expect a full Order List (from Friday’s Conference) at 9:30 ET this morning, followed at 10 by the beginning of the “March” argument session—the second-to-last two-week argument calendar of the October 2024 Term, which includes perhaps the biggest concentration of major cases from any of the separate argument calendars. We don’t currently have guidance about any decisions in argued cases coming down this week, so that’s unlikely (albeit not impossible). And although other emergency matters may reach the Court this week, the biggest pending emergency applications (in the birthright citizenship cases) won’t be ripe for a decision until the end of next week at the absolute earliest (and, realistically, not until the following week).

The One First “Long Read”:

In re Neagle and the David Terry Affair

For folks who have been reading this newsletter since the very beginning, I covered the strange-but-true story of In re Neagle in the newsletter’s first bonus issue—on November 17, 2022. But the story is worth re-telling given the moment we’re in.

Justice Stephen Field was a character. One of the many Americans who flocked to California during the late-1840s Gold Rush, Field quickly became a leading lawyer in the state, winning election to the California Supreme Court in 1857, and becoming Chief Justice of California (replacing David Terry, about whom more in a moment) in 1859. As a jurist, Field’s reputation was … ornery. One of his critics suggested that those who analyzed his life would find it to be a “series of little-mindedness, meanlinesses, of braggadocio, pusillanimity, and contemptible vanity.” A notorious holder of grudges, one contemporary observed that “when Field hates, he hates for keeps.”

His personal foibles aside, Field was a staunch Unionist. So when Congress added a new (tenth) seat to the Supreme Court in 1863 to account for the new California-based federal courts (yes, there were two brief periods where there were ten justices serving at once), Field was at the top of a very short list of lawyers suitable for nomination. He ended up serving on the Court for 34 years, deliberately staying on the bench even after his faculties declined because he wanted to break Chief Justice John Marshall’s then-record for longest-serving Justice (he’d eventually best Marshall by 33 days, only to be overtaken by Justice William Douglas in 1973). And Field is perhaps best remembered for his commitment to free enterprise unchecked by government regulation—one of the most ardent supporters of property rights in the Court’s history.

But Field was also the key figure in the events giving rise to a constitutional dispute that reached the Supreme Court in 1890. While “riding circuit” (sitting as a circuit judge) in California, Field had presided over a contentious case involving a claim by Sarah Althea Hill, represented by her then-husband Terry (Field’s former colleague on the California Supreme Court, who, among lots of other notoriety, had killed then-Senator David Broderick in an 1859 duel), that Hill had previously been married to a silver baron (Senator William Sharon of Nevada), and was therefore entitled to a share of his estate. (My friend and gifted Supreme Court observer Garrett Epps recounted much of the background for The Atlantic in 2016.)

Senator Sharon had denied Hill’s claim and sued her in federal court in an attempt to stop her from using his name. Hill hired Terry, who she’d later marry, as her lawyer. The district court ruled for Sharon, concluding that the marriage license was a forgery. Hill appealed to the circuit court—and, thus, to Field (Sharon died while the appeal was pending, leading Hill to produce what she claimed was a will in which Sharon had left his assets to Hill).

On September 3, 1888, Field read out the circuit court’s ruling affirming the district court, ruling against Hill (and Terry), and concluding that the will was also a forgery. And, although accounts differ as to who started it, Field eventually held both of them in contempt (and sent them to jail) for causing a scene in the San Francisco courtroom. Later that year, the Supreme Court (with Field recused) denied Terry’s petition for a writ of habeas corpus, sustaining the circuit court’s power to jail him for contempt.

Terry vowed revenge. When Field returned to California in June 1889 to once again ride circuit, the Attorney General ordered the local U.S. Attorney to assign Field a bodyguard. The U.S. Attorney assigned Deputy U.S. Marshal David Neagle to accompany Field, in case Terry tried to make good on his threat. Sure enough, when Terry and Field ended up on the same overnight train from Los Angeles to San Francisco on August 14, matters came to a head. Terry tried to attack Field at a breakfast stop in Lathrop. According to witnesses, after Terry slapped Field, Neagle raised his pistol and shouted “Stop! Stop! I am an officer!” When Terry reached into his pocket, Neagle killed him with two shots.

Hill swore out murder charges against Field and Neagle, both of whom were arrested by the San Joaquin County sheriff (surely the only time in American history that a sitting Supreme Court justice has been arrested on felony charges). But although Field was quickly released (there is some debate as to whether his release had required a writ of habeas corpus), Neagle’s case was harder. The issue Neagle’s case raised was that Congress had never specifically authorized his appointment. So whether he was acting lawfully in defense of Field when he shot and killed Terry arguably turned on whether the U.S. Attorney had the unilateral legal authority to deputize him—whether the Constitution gave the executive branch the power to protect key federal officers even if Congress hadn’t provided for it.

The dispute reached the Supreme Court the next year. Writing for the Court, Justice Samuel Miller upheld Neagle’s appointment: “We cannot doubt the power of the president to take measures for the protection of a judge of one of the courts of the United States who, while in the discharge of the duties of his office, is threatened with a personal attack which may probably result in his death.” In that respect, the decision in In re Neagle was an important (if modest) precedent for the executive branch’s power to act in some instances without express statutory authorization—although Congress has long-since closed the specific gap for protecting the Justices.

But the best (or craziest) part of the Court’s decision in Neagle (from which Justice Field understandably recused) was that two of his colleagues—Justice L.Q.C. Lamar and Chief Justice Melville Fuller—dissented! In the words of Lamar (who wrote for both of them), “If the act of Terry had resulted in the death of Mr. Justice Field, would the murder of him have been a crime against the United States? … [N]o such statute has yet been pointed out.”

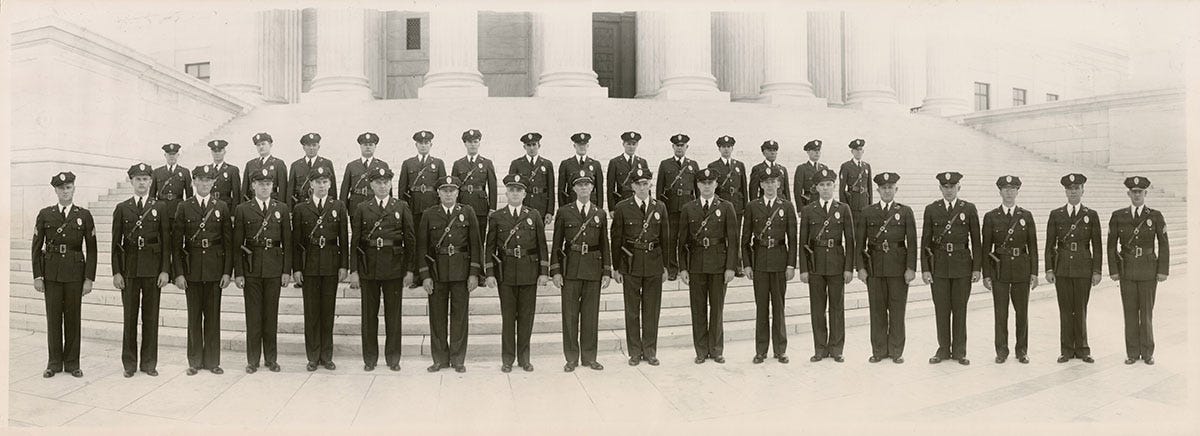

SCOTUS Trivia: The Supreme Court Police

Neagle thus establishes that the executive branch has the inherent power to protect federal judges and justices from harm. And Congress has since imposed upon the executive branch the statutory obligation to do so. But what if we ever reached a scenario in which the executive branch refused to carry out that obligation?

Since the opening of the Supreme Court Building in 1935, the Supreme Court has had its own police force—under the supervision of the Marshal of the Court, who is herself appointed by the Court. Today, by statute, the Supreme Court Police has the authority not just to protect the Supreme Court Building (and anyone inside it), but

in any location, to protect—

(A) the Chief Justice, any Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, and any official guest of the Supreme Court;

(B) any officer or employee of the Supreme Court while that officer or employee is performing official duties; and

(C) any member of the immediate family of the Chief Justice, any Associate Justice, or any officer of the Supreme Court if the Marshal determines such protection is necessary.

Whether the lower federal courts should have comparable control over at least some of their own security is a question that historically has been entirely academic. Here’s hoping it stays that way.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone (no later than) next Monday.

Until then, please stay safe out there…

This was, I gather, the point that Judge Jones was trying to make, however inartfully, on our November 2024 panel at the Federalist Society National Convention. It seems to me that it’s the behavior we’re seeing today, and not nerdy critiques of federal litigation practices, that warrants such a forceful response. But your mileage may vary.

“Court Security Officers” are, technically, part of the U.S. Marshal’s Service.

Off topic a bit, but I thought your comment at the end of the conversation with Joyce Vance yesterday about dog killing being disqualifying for public office was priceless.

Professor Vladeck, thank you for drawing an important distinction: "trying to physically intimidate judges is inconsistent with foundational principles of judicial independence." Trying to intimidate a judge with the express or implicit threat of imposing physical or fiscal harm on the judge or a family member is an intolerable act. But people (including judges) are intimidated by much more than threats of physical or fiscal harm

Like you, I was critical of the 2024 Year End Report delivered by Chief Justice Roberts. He (inexcusably) failed draw the crucial distinction that you did draw:

He went far too far in contending that “defiance directed at judges because of their work undermine[s] our Republic” and is “wholly unacceptable.” He more carefully clarified that “illegitimate activity” that “threaten the independence of judges" (i.e., from everything except the law) is limited to “(1) violence, (2) intimidation, (3) disinformation, and (4) threats to defy lawfully entered judgments.”

But careless use of the word "intimidation" can be (and will be and almost certainly has been) abused by judges to unconstitutionally punish (retaliate) against lawyers or litigants for mere verbal criticism. That, to use the words of Chief Justice Roberts, is “wholly unacceptable,” as accentuated in his own (2024) Year End Report:

“Chief Justice Taft is the only person to have served as head of the judicial and a political branch [as chief justice after having served as president]. As he put it, ‘Nothing tends more to render judges careful in their decisions and anxiously solicitous to do exact justice than the consciousness that every act of theirs is to be subject to the intelligent scrutiny of their fellow men, and to their candid criticism.’”

“It should be no surprise that judicial rulings can provoke strong and passionate reactions. And those expressions of public sentiment—whether criticism or praise—are not threats to judicial independence.”

“In [our] democracy” with “robust First Amendment protections—criticism comes with the territory. It can be healthy. As Chief Justice Rehnquist wrote, “[a] natural consequence of life tenure should be the ability to benefit from informed criticism from legislators, the bar, academy, and the public.”

The Founders of our nation and the Framers of our Constitution (and a respectable quantity and quality of SCOTUS justices) emphasized that sometimes in some ways public servants should be "intimidated." Doing so is not only proper, but even necessary. See, e.g., "October 26, 1774, a Date that Should Live in First Amendment History" at https://open.substack.com/pub/blackcollarcrime/p/october-26-1774-a-date-that-should?r=30ufvh&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false