131. Five Questions About the Khalil Case

The government's arrest and detention of a pro-Palestinian Columbia student (and green card holder) raises difficult questions about both technical immigration statutes and the First Amendment.

Welcome back to “One First,” an (increasingly frequent) newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

By now, you’ve probably seen at least some reporting on the case of Mahmoud Khalil, a Columbia University student and Syrian national who was arrested Saturday night in New York by immigration authorities—even though he has a “green card” (meaning that he is a “lawful permanent resident” under federal immigration law).

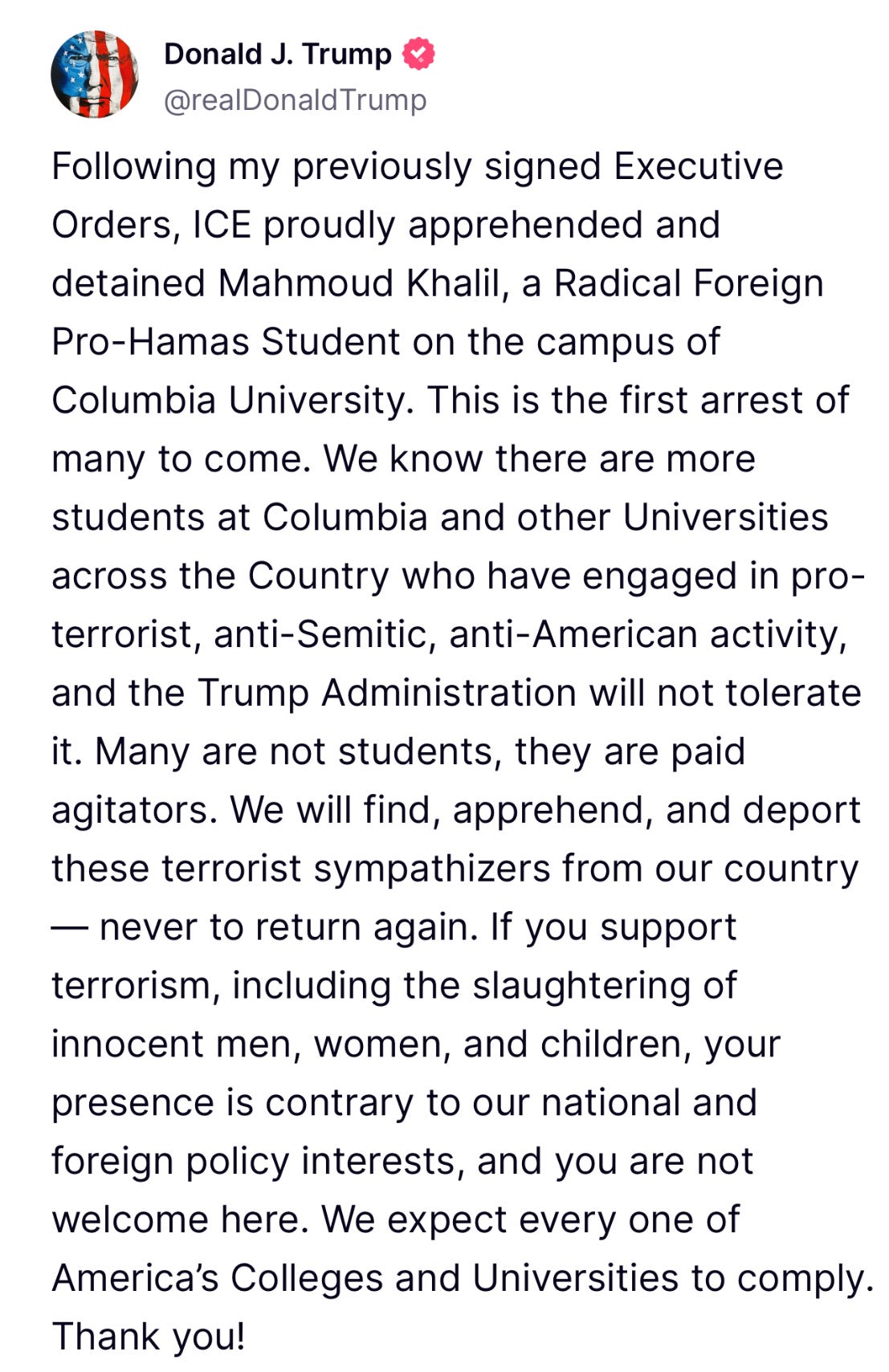

Khalil appears to currently be in immigration detention in Jena, Louisiana. And earlier today, President Trump posted the following on TruthSocial:

There is quite a lot we don’t yet know about the authorities on which the federal government is purporting to rely—not just to arrest Khalil, but to revoke (or attempt to revoke) his green card and seek his removal from the United States. Lawyers representing Khalil have already filed a habeas petition in the Southern District of New York—where it has been assigned to Judge Jesse Furman. They’ve also filed a motion seeking Khalil’s return to New York for the duration of the litigation of his habeas petition. Although he hasn’t yet ruled on that motion, Judge Furman has already temporarily barred the government from removing Khalil from the United States pending further proceedings in his court.

Presumably, that litigation will help bring at least some clarity to what the heck the government is doing. But to help preview what’s to come (and to try to separate out where the government clearly has authority from where things are … less clear), this post takes a stab at sketching out at least five big (sets of) questions that are likely going to have a lot to say about what happens from here.

To spoil the punchline, although what the government has done to this point is profoundly disturbing, and is, in my view, unconstitutional retaliation for First Amendment-protected speech, I’m not sure it is as clearly unlawful as a lot of folks online have suggested. And that’s a pretty big problem all by itself.

First, where is Khalil’s case going to be resolved?

This may seem like a strange place to start, but it matters quite a bit. As noted above, Khalil’s lawyers filed his habeas petition in federal court in Manhattan. But Khalil is currently being held in Jena, Louisiana—which is in the Alexandria Division of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Louisiana (and, as importantly, the Fifth Circuit). It wouldn’t surprise me at all if the government tried to argue that the New York federal courts lack jurisdiction over Khalil’s petition—because they lack jurisdiction over his “immediate custodian,” i.e., the head of the ICE detention facility in Jena. Indeed, this is the exact argument on which the Bush administration prevailed in the Supreme Court in the Jose Padilla case in 2004—when a U.S. citizen detained in South Carolina as an “enemy combatant” sought to challenge his detention in Manhattan, which is where he had last been before he was transferred to military custody.

But there are two potential grounds on which Padilla can be distinguished. First, in Padilla, the habeas petition wasn’t filed until after Padilla had been physically removed from the Southern District of New York. Here, Khalil’s lawyers have represented that they filed before he was transferred to Louisiana (at 4:40 a.m., no less!). If that’s true (and there’s no reason to believe that it isn’t), that would make this a very different case. After all, a different line of Supreme Court precedent provides that the federal government can’t defeat jurisdiction in a habeas case by transferring the petitioner after the petition is filed.

Second, Padilla itself distinguished immigration cases—declining to decide whether the Attorney General (who’d be subject to jurisdiction in any federal district court) is a proper respondent in those cases.1 If the answer is “yes,” then Khalil’s case could potentially remain in New York even if he was transferred before it was filed. Either way, though, expect at least some of the dispute in the case to focus on whether it’s properly in the Southern District of New York in the first place.2

Second, what is the legal basis pursuant to which Khalil was arrested?

A lot of the public commentary surrounding Khalil’s case focuses on the fact that he has a green card. That’s true, but it doesn’t actually provide him with any special protection against immigration arrest and detention. Indeed, there’s no special requirement that a lawful permanent resident (LPR)’s status be revoked before they are arrested and detained; the revocation can (and often does) come as part of the removal proceeding.

As significantly, although LPRs have due process rights approaching those of U.S. citizens, the Supreme Court held in Demore v. Kim in 2003 that the Due Process Clause does not preclude their detention pending their removal, even without an individualized determination of risk. LPRs in removal proceedings have statutory and constitutional rights to challenge the factual and legal basis on which the government is seeking to remove them. But LPRs are not generally exempt from arrest and detention pending removal.

Instead, the second question is what the government’s legal basis was for Khalil’s arrest. As relevant here, ICE officers can make warrantless arrests only when they have “reason to believe that the alien so arrested is in the United States in violation of any [relevant immigration] law or regulation and is likely to escape before a warrant can be obtained for his arrest.” The “reason to believe” standard has generally been viewed as equivalent to probable cause. Thus, to sustain the lawfulness of Khalil’s arrest, the government has to identify the specific basis on which it believes that Khalil is subject to removal.

Third, what is the legal basis pursuant to which the government is seeking to remove Khalil?

This brings us to the central “merits” question. What is the exact basis on which Khalil, in the government’s view, is subject to removal from the United States? Suffice it to say, President Trump’s social media post is not exactly specific here, nor has Secretary of State Rubio provided much additional clarity.

For what it’s worth, my best guess (and it is only a guess) is that the government is going to rely upon one or both of two very specific provision of immigration law.

The first, 8 U.S.C. § 1227(a)(4)(C), provides that “An alien whose presence or activities in the United States the Secretary of State has reasonable ground to believe would have potentially serious adverse foreign policy consequences for the United States is deportable.” There’s a caveat protecting such a non-citizen from removal “because of the alien’s past, current, or expected beliefs, statements, or associations, if such beliefs, statements, or associations would be lawful within the United States,” but only “unless the Secretary of State personally determines that the alien’s [continued presence] would compromise a compelling United States foreign policy interest.” Thus, if Secretary Rubio makes (or has made) such a personal determination, that would provide at least an outwardly lawful basis for pursuing Khalil’s removal—so long as Rubio has also made timely notifications of his determinations to the chairs of the House Foreign Affairs, Senate Foreign Relations, and House and Senate Judiciary Committees required by 8 U.S.C. § 1182(a)(3)(C)(iv). (I’ve seen no evidence that he’s done so, but that doesn’t mean he hasn’t.)

The second provision is 8 U.S.C. § 1182(a)(3)(B)(i)(VII), which renders both inadmissible and removable any non-citizen who “endorses or espouses terrorist activity or persuades others to endorse or espouse terrorist activity or support a terrorist organization.” Perhaps the argument is going to be that, insofar as Khalil was involved in organizing pro-Palestinian protests on Columbia’s campus, he was “endors[ing] or espous[ing]” terrorist activity (to wit, by Hamas).

I know there’s a lot of technical language here. The key point is that it’s at least possible that the government has a non-frivolous case for seeking Khalil’s removal under one or both of these provisions—especially if Secretary Rubio invoked § 1227(a)(4)(C). And insofar as the government is relying upon those provisions to pursue Khalil’s removal, that might bring with it a sufficient statutory basis for his arrest and detention pending his removal proceeding. We’ll see what the government actually says when it files a defense of its behavior before Judge Furman; for present purposes, it seems worth stressing that there may well be a legal basis for its deeply troubling conduct.

Fourth, to what extent does the First Amendment affect these analyses?

Now we get to the hard and important part—the unshakable appearance, if not the reality, that all of this is being done in retaliation for constitutionally protected speech on Khalil’s part. It seems to me that there are three different places where the First Amendment might show up in the litigation over what’s happened: As a challenge to the constitutionality of each of the two grounds on which I’m speculating the government might claim it can remove him; and as a standalone retaliation claim.

Taking the third possibility first, the problem for Khalil is that the Supreme Court, in general, has made it very difficult to use a First Amendment retaliation claim to successfully defeat an enforcement proceeding otherwise supported by probable cause—and especially in immigration cases. In its 1999 ruling in Reno v. American-Arab Antidiscrimination Committee, for instance, the Court stressed that “As a general matter . . . an alien unlawfully in this country has no constitutional right to assert selective enforcement as a defense against his deportation.” To be sure, Justice Scalia’s majority opinion left open the possibility that there could be “a rare case in which the alleged basis of discrimination is so outrageous” as to bar an otherwise valid removal proceeding. This may well be such a case. And the plaintiffs in AADC were not LPRs—which might put even more force into the argument for First Amendment limits here. But it’s worth starting from the baseline that, for better or worse (and, in my view, for worse), the First Amendment doesn’t generally protect non-citizens against being removed for activity that the First Amendment protects.

I’m a bit more sanguine about the possibility of specific First Amendment challenges to the hypothesized grounds for Khalil’s removal. Among other things, the First Amendment might require the Secretary of State to have substantial support for a personal determination that an LPR’s continued presence “would compromise a compelling United States foreign policy interest,” support that, in turn, courts could subject to meaningful scrutiny.

Likewise, the First Amendment might limit the government from removing LPRs for doing nothing more than “endors[ing]” or “espous[ing]” terrorist activity (one might also imagine a Fifth Amendment challenge on the ground that those terms are unconstitutionally vague). The devil will very much be in the details. But with the necessary caveat that I’m only speculating as to the grounds on which the government will even rely, it strikes me that these will be the critical constitutional questions raised by Khalil’s habeas petition if and when it gets to the merits. I would certainly hope that the federal courts will read the Constitution to require the government to have an awfully compelling reason for removing a specific LPR in circumstances like these—and I suspect that no such reason exists in Khalil’s case. But that’s what the litigation is going to test; it’s not something about which I can be confident at this stage.

Fifth, and finally, is this really who we are?

At least as I’m writing this post, these appears to be the big legal questions. I’m sure I’ve missed something. And other points may arise as we learn more about the government’s position. So I apologize in advance for not covering the waterfront.

But I can’t write a post about this case without taking a moment to step back and reflect on what, exactly, is happening here. If the government had said that “there’s one specific LPR who is responsible for a unique amount of unlawful behavior relating to pro-Palestinian protests, and his case is special,” that would be one thing. But President Trump’s social media post makes clear that, at least from his perspective, Khalil’s is not a special case. And that, to me, is the scariest part—for it suggests that the government intends to use these rarely invoked removal authorities in enough cases to seek to deter non-citizens of any immigration status from speaking out about sensitive political issues, even in contexts in which the First Amendment does, or at least should, clearly protect their right to do so.

Conflating “pro-terrorist,” “anti-Semitic,” and “anti-American” activity is an incredibly dangerous step to take. The first one of those three may well render even a green card holder subject to removal. The second and third, by themselves, shouldn’t. And so although the government may have a bit more of a legal leg to stand on in Khalil’s case than one might’ve assumed at first blush, it sure doesn’t seem like it’s entitled to the benefit of any doubt as this case goes forward. If anything is anti-American, it’s threatening non-citizens who are in this country legally and have committed no crimes with the specter of being arrested, detained, and removed for doing nothing more than speaking up on behalf of unpopular causes—even, if not especially, unpopular causes with which many of us may well disagree.

If you’ve enjoyed this issue of the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider subscribing if you don’t already, and perhaps even a paid subscription if you’re able and willing to support the work that goes into it:

We’ll be back (no later than) Thursday with our regularly scheduled weekly bonus issue. Until then, stay safe out there.

Today, it would be the Secretary of Homeland Security. But the relevant law that the Padilla Court was summarizing involved the pre-DHS legal regime—in which immigration enforcement was part of DOJ.

The government may also argue that, insofar as what Khalil is really challenging is his pending removal proceedings and not his detention pending those proceedings, he has to wait to bring that challenge until there’s a final order of removal—at which point he can petition for review in the Fifth Circuit rather than file a habeas petition. Obviously, that will also be a significant jurisdictional issue for the district court to sort through.

Thank you very much for making the effort to write this.

First they came for the Palestinians...