129. Untangling the Foreign Aid Ruling

There's a lot going on in the Court's cryptic, 5-4 ruling in the foreign aid funding cases. Here's my (very) quick attempt to unpack some of the most important takeaways.

Welcome back to “One First,” an (increasingly frequent) newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Given the widespread confusion arising from the Supreme Court’s 5-4 ruling this morning in the foreign aid spending cases, I thought it would be worth an unscheduled issue that took a stab at summarizing what the Court did (or appears to have done), what it didn’t do, and what happens next. I’m writing this from an airport gate waiting area, so please forgive me if it’s a little less … organized … than the typical posts.

I. Background

If you’re not familiar with the background to these cases, I’d encourage you to read my post from last Thursday, which went into at least some detail on how these cases got to the Supreme Court, the “administrative stay” that Chief Justice Roberts entered last Wednesday, and the very different ways of understanding the Chief’s intervention. (I should concede that even that post barely scratched the surface of how intricate and complicated this litigation is—the cases aren’t just about the merits of whether the executive branch can unilaterally stop spending these funds; there’s a bunch of messy procedural stuff, too, at least some of which has been complicated by the government’s … shifting … litigation positions.)

For present purposes, the key, in my view, is understanding that there are two different sets of rulings here. There’s Judge Ali’s underlying temporary restraining order, which remains in effect (and which the government has neither tried to appeal nor seek emergency relief from), and then there’s Judge Ali’s more specific order, which purported to enforce the TRO by obliging the government to pay somewhere between $1.5 and $2 billion of obligated foreign aid funds by last Wednesday night (February 26). It was that order that the government tried to appeal, and from which it sought emergency relief first in the D.C. Circuit, and then in the Supreme Court. By issuing an “administrative stay” last Wednesday night, Chief Justice Roberts temporarily absolved the government of its obligation to comply with that order—but not with the underlying TRO, which generally requires the government to spend money Congress has appropriated for foreign aid funding.

II. Wednesday Morning’s Order

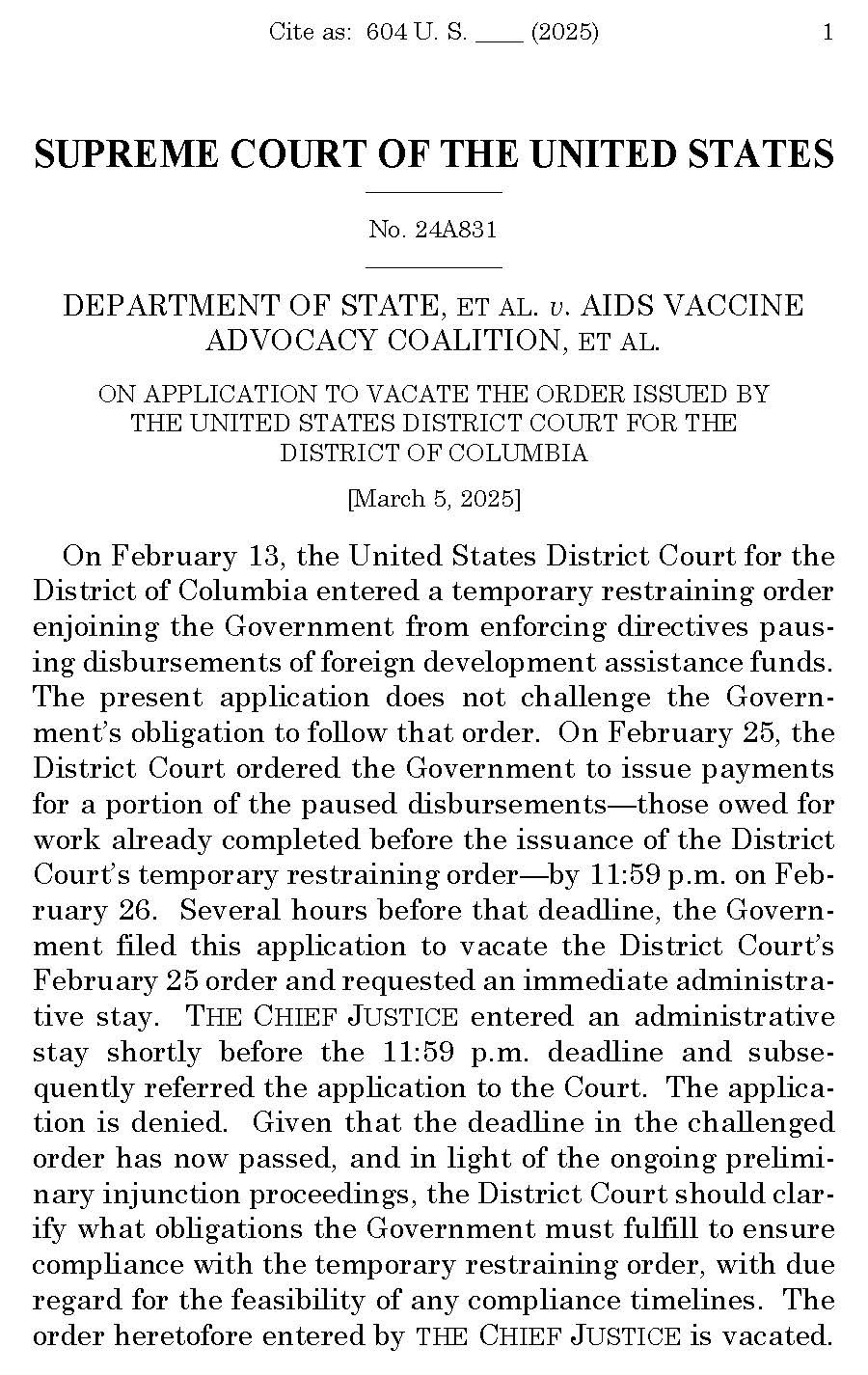

Against that backdrop, the Court’s Wednesday morning ruling is more than a little confusing. Let’s start with what’s clear: A 5-4 majority (with Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Barrett joining the Democratic appointees) denied the government’s application to vacate Judge Ali’s enforcement order. There’s only one meaningful sentence in the Court’s ruling, and it is maddeningly opaque:

Given that the deadline in the challenged order has now passed, and in light of the ongoing preliminary injunction proceedings, the District Court should clarify what obligations the Government must fulfill to ensure compliance with the temporary restraining order, with due regard for the feasibility of any compliance timelines.

This sentence (or, perhaps, a broader earlier draft) provoked a fiery (and more-than-a-little hypocritical) eight-page dissent from Justice Alito, joined in full by Justices Thomas, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh. But before getting to the dissent, let me try to read a couple of tea leaves out of this cryptic but important passage.

First, I think it’s meaningful that the majority denied the government’s application, rather than dismissing it as “moot.” In English, that is the majority signaling that the government likely still must comply with the “pay now” order, albeit not on the original timeline. If the majority thought that the “pay now” order was no longer live because the deadline had come and gone, then the proper disposition would’ve been to dismiss the application as moot, not to deny it. (Indeed, although there are good reasons to not rely upon dissents to figure out what the majority held, Justice Alito’s dissent seems to reinforce this reading.) This may seem like a very thin reed, but it’s a distinction I can’t imagine was lost upon the justices. The majority (and, apparently, the dissent) seem to agree that the government remains under not just the general obligation of the original TRO, but the specific obligation of the “pay now” order.

Second, the clause about the district court “clarify[ing]” the obligations the government must fulfill to comply with the TRO strikes me as an invitation to Judge Ali to do exactly that—to issue a more specific order that (1) identifies the particular spending commitments he believes the government must honor to comply with the TRO; and (2) gives the government at least a little more than 48 hours to do so. (Yes, the underlying TRO has now been in place for 23 days, which should’ve been enough time already. More on this below, too.) The upshot is that, even if the Trump administration doesn’t have to pay the money immediately, it will have to do so very soon. That’s small solace to the organizations and people who have already had their lives upended by the spending freeze, but it’s a bigger loss for the Trump administration than the text may suggest.

Third, the timing of the ruling is striking. The Court handed down the order right at 9 a.m. this morning—less than 12 hours after the end of President Trump’s Tuesday night address to Congress. It is just about impossible to imagine that the ruling was still being finalized overnight (or that the Chief Justice was somehow influenced by his … awkward … moment with Trump). If not, then there appears to have been at least some choice on the Court’s part to hand down the ruling after the President’s speech, and not before it, e.g., at the close of business yesterday—perhaps to avoid the specter of Trump attacking the justices while several of them were in the audience? I’ve written before about the specter of the Court timing its rulings. This at least seems like it might be another example.

And fourth, here’s that 5-4 lineup again. Back in January, I wrote about how this particular 5-4 alignment (with the Chief Justice and Justice Barrett joining the three Democratic appointees) is starting to show up in cases

in which the Chief Justice’s elusive but not illusory institutional commitments, and Justice Barrett’s emerging independence, are separating them from the other Republican appointees. For a host of reasons that I suspect are obvious, we may see more such cases sooner rather than later.

On one hand, it’s a bit alarming that Justice Kavanaugh joined the dissent (about which more in a moment). On the other hand, for those hoping that the Court is going to be a bulwark against the (mounting) abuses of the Trump administration, it’s a cautiously optimistic sign that there may well be at least five votes for that broader (but yet to be proven) proposition.

III. The Dissent

Justice Alito’s dissent goes on quite a journey in eight pages. As is, unfortunately, often the case with respect to his dissents from emergency applications, it combines a remarkable amount of hypocrisy with statements that are either materially incorrect or, at the very least, misleading.

On page 3 of the ruling (page 2 of the dissent), for example, Alito writes that “the Government must apparently pay the $2 billion posthaste—not because the law requires it, but simply because a District Judge so ordered.” Of course, this completely misstates both the theory of the plaintiffs’ lawsuits and the gravamen of Judge Ali’s order. The whole point is that the law does require it—that Congress has mandated the spending and that the contractual obligations have been fulfilled. Indeed, Judge Ali’s “pay now” order is about work already completed for which the money was already due. If there is authority for the proposition that the government is not legally obliged to pay its bills, Alito doesn’t cite it. Yes, there may be separate questions about the court’s power to compel the government (more on that shortly), but that’s not the same thing as whether the “law requires” … the government to pay its bills. Do the dissenters genuinely believe that the answer is no?

Alito also makes much out of the argument that sovereign immunity bars the claims against the government. But the Supreme Court has already held that relief under the Administrative Procedure Act can run to whether the government is obliged to pay expenditures to which the recipients are legally entitled. Alito asserts that actually ordering the government to pay those expenditures is something else entirely; suffice it to say, I think that’s slicing the bologna pretty thin… Again, I think his argument would have more force if Judge Ali’s “pay now” order was about funds for which the administrative processes haven’t fully run. But here, they have. And so it’s just a question of whether federal courts have the power to force the government to … enforce the law.

In that respect, contrast Alito’s analysis here with his dissenting opinion in United States v. Texas—in which he would’ve upheld an injunction by a single (judge-shopped) district judge that effectively dictated to the executive branch what its immigration enforcement priorities must be. In explaining why the Biden administration should lose, he wrote:

nothing in our precedents even remotely supports this grossly inflated conception of “executive Power,” which seriously infringes the “legislative Powers” that the Constitution grants to Congress. At issue here is Congress’s authority to control immigration, and “[t]his Court has repeatedly emphasized that ‘over no conceivable subject is the legislative power of Congress more complete than it is over’ the admission of aliens.” In the exercise of that power, Congress passed and President Clinton signed a law that commands the detention and removal of aliens who have been convicted of certain particularly dangerous crimes. The Secretary of Homeland Security, however, has instructed his agents to disobey this legislative command and instead follow a different policy that is more to his liking.

In 2023, Alito dismissed the view that courts could not push back against the President in such cases as a “radical theory.” In 2025, apparently, it’s correct. I wonder what changed?

Finally, Alito offers this … remarkable … discussion of why the harm the plaintiffs are suffering is insufficient to overcome the government’s case for a stay:

any harm resulting from the failure to pay amounts that the law requires would have been diminished, if not eliminated, if the Court of Appeals had promptly decided the merits of the Government’s appeal, which it should not have dismissed. If we sent this case back to the Court of Appeals, it could still render a prompt decision

In other words, the plaintiffs are being harmed not by the government’s refusal to pay them, but by the D.C. Circuit’s refusal to exercise appellate jurisdiction over Judge Ali’s “pay now” order. I don’t even know what to say about this argument other than that, if that’s how irreparable harm worked, well, emergency relief (and the role of intermediate appellate courts) would look a heck of a lot different.

Alito closes by accusing the majority of “impos[ing] a $2 billion penalty on American taxpayers.” This comes back to the central analytical flaw in the dissent: The “penalty” to which Alito is referring is the government’s underlying legal obligation to pay its debts. Debts aren’t a “penalty”; they are the literal cost of doing business. And if this is the approach these four justices are going to take in all of the spending cases to come, that’s more than a little disheartening.

IV. What’s Next?

If you’ve made it this far, congratulations. As for what comes next, well, I’m not entirely sure. We know that Judge Ali is scheduled to hold a preliminary injunction hearing tomorrow (Thursday). It is very possible that, before then (or shortly thereafter), he will reimpose some kind of “pay now” mandate that, with the hints from the Supreme Court majority, is a bit more specific and has a slightly longer timeline. Of course, the government could seek emergency relief from that order, too, but I take today’s ruling as a sign that, so long as Judge Ali follows the Court’s clues, at least five justices will be inclined to deny such relief. That doesn’t do anything immediately for the plaintiffs and other foreign aid recipients who are continuing to suffer debilitating consequences. But it does suggest that, sometime soon, the government really is going to have to pay out at least some of the money at issue in these cases (and, as importantly, perhaps other funding cases, too).

The broader takeaway, though, is the role of the Court in Trump cases. This is now the second ruling (including Dellinger) in which the Court has, in the same ruling, (1) moved gingerly; but (2) denied the relief that the Trump administration was seeking. Two cases are, obviously, a small data set. But for those hoping/expecting that even this Supreme Court will stand up, at least in some respects, to the Trump administration, I think there’s a reason to see today’s ruling as a modestly positive sign in that direction. Yes, the Court could do even more to push back in these cases. But the fact that Trump is already 0-2 on emergency applications is, I think, not an accident, and a result that may send a message to lower courts, whether deliberately or not, to keep doing (most of) what they’re doing.

If you’ve enjoyed this issue of the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider subscribing if you don’t already, and perhaps even a paid subscription if you’re able and willing to support the work that goes into it:

Either way, we’ll be back with our weekly “bonus” issue tomorrow. Happy Wednesday, all!

Hey, thank you from writing from an airport gate! This is super helpful!

I was really hoping you would weigh in on this ruling—thank you. I expect this spittle-flecked intemperance from Alito but I must say I find it a bit alarming that the other three would sign on to that language. This seems also an alarmingly pointed attack on a district court judge—it comes off as more an effort at intimidation than a coherent effort to articulate legal error.