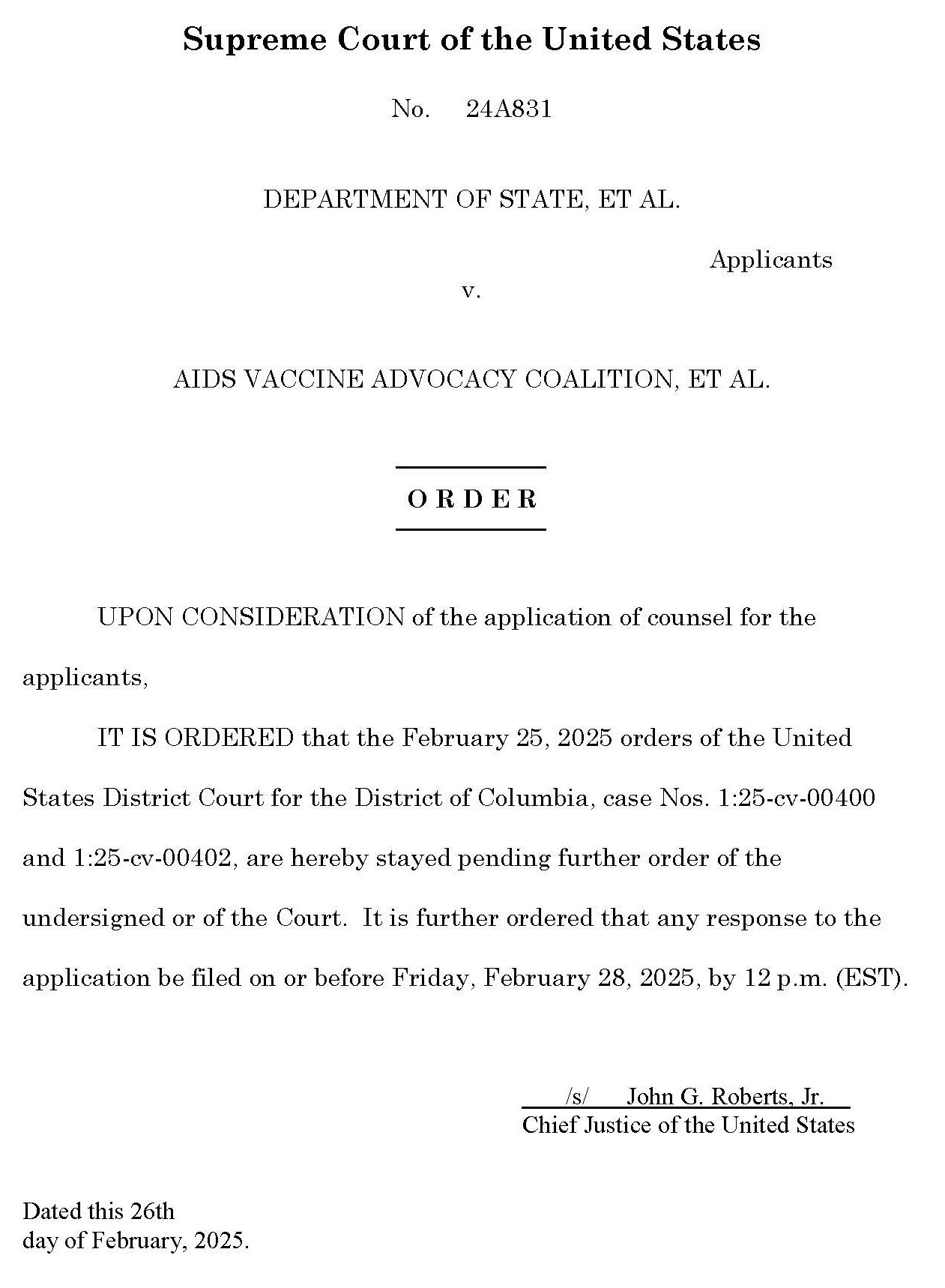

127. Chief Justice Roberts's Administrative Stay in the Foreign Aid Funding Cases

There are two very different ways to understand Wednesday night's order temporarily absolving the government from spending $1.5 billion in obligated funds. We'll know soon enough which one is correct.

Welcome back to “One First,” an (increasingly frequent) newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

I wanted to send out a second issue today (on top of the normal Thursday “bonus” issue) because there is a ton of misinformation and misunderstanding out there concerning Chief Justice Roberts’s single-justice order last night in two of the foreign aid spending cases—which temporarily paused a district court’s mandate that the government spend $1.5 billion in already obligated funds by 11:59 p.m. last night.

As I explain in the post that follows, there are two very different ways to understand why Chief Justice Roberts intervened last night—one of which is deeply ominous, and one of which, while understandably frustrating, is also at least institutionally defensible. My own suspicion is that the latter reading is the more likely one. But the key for present purposes is that we’ll all find out soon enough which reading is the correct one.

The Procedural Background

By way of very quick background, at issue here are two of a number of suits that have been brought challenging the Trump administration’s attempts to refuse to spend money that Congress has appropriated—and, in many instances, that the government has already committed to spending. (For more background on the “impoundment” power, see this earlier post.)

These two cases, AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition v. Department of State and Global Health Council v. Trump, both involve the government’s sweeping cut-off of foreign aid spending. The first of the two complaints was filed in federal district court in Washington, D.C. on Monday, February 10, where it was assigned to Judge Amir Ali. (The second complaint was filed on February 11. For the rest of this post, and for ease of narrative, I’m going to treat the two cases as one.)

Here comes the nerdy stuff: On Thursday, February 13, Judge Ali entered a temporary restraining order, purporting to block the categorical suspension of foreign aid spending. Last Wednesday (February 19), the plaintiffs filed a motion to enforce the TRO (and hold the government in civil contempt), arguing that the government had not come remotely close to complying with the February 13 TRO. Judge Ali granted the motion to enforce last Thursday (without holding the government in contempt). This Monday (February 24), the plaintiffs filed a renewed motion to enforce the TRO and for contempt. Judge Ali responded Tuesday with an order specifically requiring the administration to pay all invoices and letter-of-credit drawdown requests for work completed prior to the TRO, as well as reimbursements on grants and assistance agreements, by 11:59 p.m. last night. That order is what touched off the appellate drama.

The government immediately appealed Tuesday’s order to the D.C. Circuit, and sought a “stay” of the order (to freeze it pending that appeal) from both Judge Ali and the D.C. Circuit. Judge Ali denied the stay yesterday morning. And at 8:07 p.m. last night, the D.C. Circuit issued a terse order holding that it lacked jurisdiction over the government’s appeal (which it dismissed); that the government couldn’t make out the burden for an extraordinary writ of mandamus; and that its motion for a stay was therefore moot. (Of note, the appeal is not about the merits; it is about whether Judge Ali had the power to issue the February 25 order.)

By that point, the government had already gone to Chief Justice Roberts in his capacity as Circuit Justice for the D.C. Circuit. Specifically, the government asked Roberts for a stay of the district court’s order pending its appeal, and for an immediate “administrative” stay to put off, even briefly, the 11:59 p.m. deadline for complying with Judge Ali’s February 25 order. About an hour after the D.C. Circuit ruled, Roberts issued an “administrative” stay, pausing Judge Ali’s deadline and ordering the plaintiffs to respond (by noon ET on Friday) to the government’s application for a stay for the duration of its appeal.

Two Ways to View Chief Justice Roberts’s Order

For completely understandable reasons, the Chief Justice’s intervention generated a ton of media headlines and social media reactions. Unfortunately, many of the headlines portrayed the ruling as much more than what it was, at least so far. All that Roberts has done is buy the full Court a little bit of time to sort out whether (1) the government should be allowed to appeal Judge Ali’s February 25 order; and that order should be paused during that appeal. Indeed, in the context in which the dispute reached the Supreme Court (with less than four hours before a deadline for the government to spend more than $1.5 billion), an “administrative” stay seems far preferable to having the full Court rule, with virtually no time to consider the briefs or rulings below, based only on which side the justices are more sympathetic to.

The problem, of course, is that the spending cut-off is already causing significant, and in at least some cases, irreparable harm on the ground. Thus, even a temporary pause in Judge Ali’s order exacerbates that harm. And at the most superficial level, it seems obvious that the Trump administration should ultimately lose these cases—that it lacks the power to simply stop spending money Congress has appropriated, and to stop payments on money that is already obligated.

But the question before Chief Justice Roberts last night wasn’t (solely) about who is ultimately going to win these cases; it was much more complicated: at the bottom of the government’s appeal is whether Judge Ali had the authority to specifically order the government to pay the $1.5 billion in obligated funds; along with whether the D.C. Circuit had the power to hear the government’s appeal from that order; and whether that order should be stayed while the Supreme Court sorts out both the jurisdictional question and the question about Judge Ali’s power to issue Tuesday’s order. The ultimate merits (must the government eventually pay) are obviously part of that calculus, but they’re not all of it.

That’s why there are two ways to understand what the Chief Justice did. The first (cynical) way is that it’s the first sign that he (and, presumably, a majority of the Court) are going to let Trump get away with the massive arrogation and usurpation of Congress’s appropriations power reflected in these spending cut-offs. On that view, last night’s pause is just the opening act in a series of rulings in which the Court will side with the federal government on the merits—and effectively roll over—and will intervene to prevent district courts from forcing the government to pay its bills.

The second way, and the way I, at least, reacted, is that last night’s order was simply a play for time. Although this litigation has been making headlines for two weeks, the Court itself didn’t receive anything related to it until yesterday afternoon. The D.C. Circuit didn’t rule until 8:07 p.m. And so you have a Circuit Justice trying to figure out what to do after hours, and whether he even has time to take the full Court’s temperature, with a deadline that’s less than four hours away and with a lot more going on than just the ultimate merits question.

In this scenario, the only conclusion Roberts’s order may reflect is that two extra days, however harmful they might be to some of the plaintiffs, will give the Court at least a little bit of time to make a principled, reasoned decision—rather than a knee-jerk reaction against an expiring clock. If the Supreme Court is going to clear the way for a district judge to force the federal government to turn those spending taps back on, better for the full Court to do it with at least a bit of deliberation than for a single justice to do it in a Wednesday night frenzy.

Don’t get me wrong; this second way is still problematic in the sense that it buys the government two days to which it almost certainly isn’t entitled. But it seems to me that that cost may well be worth it if the result is a full Court ruling that gets Judge Ali’s back—especially if the alternative last night would’ve been a more dramatic, and longer-lasting, pause. I can’t, of course, prove that this is what the Chief Justice was thinking. But in a bizarro world in which I was in his position, it’s probably what I would have done.

What Happens Now?

For better or worse, we should soon get a pretty good sense of which of these readings is more accurate. The Chief Justice ordered the plaintiffs to respond by noon on Friday—which creates at least the possibility that the full Court will rule by the end of the day night tomorrow. There’s no expiration on his administrative stay, so there’s no formal requirement that the Court rule by a time or date certain. But I’d be more than a little surprised if the Court doesn’t weigh in before the weekend.

When the Court weighs in, I see three possibilities: The first is that it grants the stay—a move that would almost certainly provoke loud, public dissents from some of the justices. The second is that it denies the stay and lets Judge Ali’s ruling go into effect—perhaps while stressing that the order is relatively limited in requiring payment only on those contracts that were already fulfilled. The third is that the Court decides it wants to take some version of the power-to-order-payments issue up on the merits—and so it grants expedited plenary review of Judge Ali’s order compelling payments, of the broader legality of the spending freeze, or perhaps even both.

If it’s the first scenario, then I think there will be quite a bit of support for the more cynical reading of the Chief Justice’s intervention last night. But if it’s the second or third scenario, then my own view is that we’ll end up viewing last night’s order as a responsible if frustrating attempt to give the full Court a bit more time to sort out how to handle such an important dispute—especially one that might set off a direct confrontation between the Supreme Court and the executive branch. If such a confrontation there is to be, all the more reason for the Court to take a beat before entrenching.

Either way, though, the prediction that emergency applications from the Trump administration were going to take over the Supreme Court’s Spring 2025 docket sure appear to be coming true. And I’m not sure anyone—the Court included—is the better for it.

If you’ve enjoyed this issue of the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider subscribing if you don’t already, and perhaps even a paid subscription if you’re able and willing to support the work that goes into it:

Either way, have a great weekend, all. We’ll be back (no later than) next Monday.

Thank you for this, maybe, reassuring summary. I would note that, via my son who works for one of the NGO’s involved, the Government aka Peter Marocco spent most of Wednesday canceling the remaining contracts that were on the books in order to be able to at the very least plead that it would be impossible to restore funding so quickly and also just because they are cruel and want Americans working in foreign aid to lose their jobs and people to die. I would hope that at the very least the NGO’s would be able to present this sabotage of the payment system as evidence before SCOTUS for their malign intent

I wonder whether Roberts will back Trump simply because he is afraid that Trump will defy his order and he doesn't want the Court to appear impotent. He may be more concerned with maintaining the appearance of a co-equal branch of government than with maintaining democracy. If the Court rules against Trump, maybe some Republicans will grow a backbone.