113. Direct Appeals from State Criminal Convictions

The Supreme Court's docket for the October 2024 Term includes *zero* appeals from state criminal convictions. That's part of a broader trend—and one with significant downstream implications

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current work, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

As I previewed a few posts back, I’ve been thinking/working on a broader project about changes in the shape of the Supreme Court’s “merits” docket (the cases that the justices agree to take up, hold oral argument in, and decide through full opinions). With the Court getting close to filling out its merits docket for the current (October 2024) Term, there’s a rather stunning data point that merits a post unto itself: At least as of now, the justices are set to hear precisely zero direct appeals from state criminal convictions during their current term. And although the fact that we may end up with no such cases this term may be a bit of a statistical fluke, the long-term downward trend is undeniable.

The disappearance of state criminal appeals from the justices’ docket is not just a noteworthy trend; it is a profoundly problematic one—because direct appeals from criminal convictions have historically been some of the most important vehicles through which the justices have clarified old rules of constitutional law and articulated new ones; and because, thanks to Congress and the Court, they’re increasingly the only vehicles through which new law can be made in a way that will benefit current and future criminal defendants and civil rights plaintiffs. Even if this Court might reach different answers to questions about the scope of the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Eighth Amendments than someone like me might prefer, the demise of the Court’s criminal appellate docket means that, most of the time, it isn’t providing any answers at all—a result that asymmetrically tilts litigation in favor of governments and their officers at the expense of their citizens.

But first, the news.

On the Docket

Last week brought with it the first signed opinion of the term, with Justice Jackson doing the honors in Bouarfa v. Mayorkas. A unanimous Court held that Congress had cut off judicial review of denials of visa revocations by the Secretary of State when the revocation is based upon the Secretary’s determination that the marriage forming the basis for the visa was a “sham.” It turns out that there are actually a lot of examples of statutes like these—where Congress has given the government such broad discretion over particular administrative decisions that how the government exercises that discretion is not subject to judicial review. (This may help to explain why the ruling in Bouarfa was unanimous.)

The Court also issued its second “DIG” in a case argued earlier this term—dismissing as improvidently granted the NVIDIA case. It’s a bit odd to have two post-argument DIGs in such quick succession—and raises questions we’ll never be able to answer about how well (or not) the internal processes for identifying cases worth deciding are functioning.

Last Monday’s Order List brought with it five separate opinions respecting denials of certiorari—including a fairly remarkable dissent from Justice Alito about the difficulties plaintiffs have establishing standing when they’re challenging alleged governmental misconduct that they have no evidence actually occurred. (It’s remarkable because the precedent that makes it hard for plaintiffs to establish standing in such cases is the Court’s 2013 5-4 ruling in Clapper v. Amnesty International, in which the majority opinion was written by … Justice Alito). The Court also added two potentially significant cases to its docket on Friday—a technical dispute about standing in a particular type of environmental law suit (where the bigger news is that the Court didn’t agree to take up the merits—it granted certiorari only on one of the questions presented); and a messy but important case about the relationship between the First Amendment and state religious exemptions from unemployment taxes. And on the emergency side, the full Court, with no public dissents, denied a request from a Kentucky utility company to block the EPA’s “coal ash rule.”

Speaking of emergency applications, other than a regular Order List at 9:30 ET, the real news from the Court this week may well involve TikTok. Back on December 6, the D.C. Circuit had rejected TikTok’s constitutional challenge to the statute Congress enacted earlier this year that effectively requires U.S. companies to stop supporting TikTok (including by making it no longer available in app stores) if TikTok’s Chinese owners haven’t effectively divested from the company by January 19. Late last Friday, the court of appeals also rejected TikTok’s request for emergency relief—filing a brief, two-page order explaining why TikTok couldn’t meet its burden for a temporary injunction of that statute pending an appeal to the Supreme Court. It seems inevitable that TikTok will now ask the Supreme Court to intervene. I’m planning to have more to say about the dispute in this week’s bonus issue on Thursday; for now, let me just flag that, among other things, it will shape up to be a fascinating test case for the appropriate standard for relief in such cases—which the Court has not always been … great … about following.

Stay tuned.

The One First “Long Read”:

Criminal Appeals and “Clearly Established” Law

Today’s “Long Read” really has two distinct parts—a descriptive claim about the disappearance from the Court’s docket of direct appeals from state criminal convictions (and a simultaneous reduction in other criminal appeals); and a more prescriptive claim about why that disappearance is a problem worth a solution. Let’s take these in turn.

Documenting the Decline of Direct State Criminal Appeals

The data at the heart of this post comes from two sources: the Supreme Court’s own “Granted/Noted Cases” lists for each term dating back to the October 2007 Term—all of which are available on the Court’s website; and, for earlier years, the “Statistics” compiled each November by the Harvard Law Review. Unlike some of the Court’s other data, the Granted/Noted Cases lists capture exactly what we want—every case that received plenary review from the Court and was decided during the term at issue.

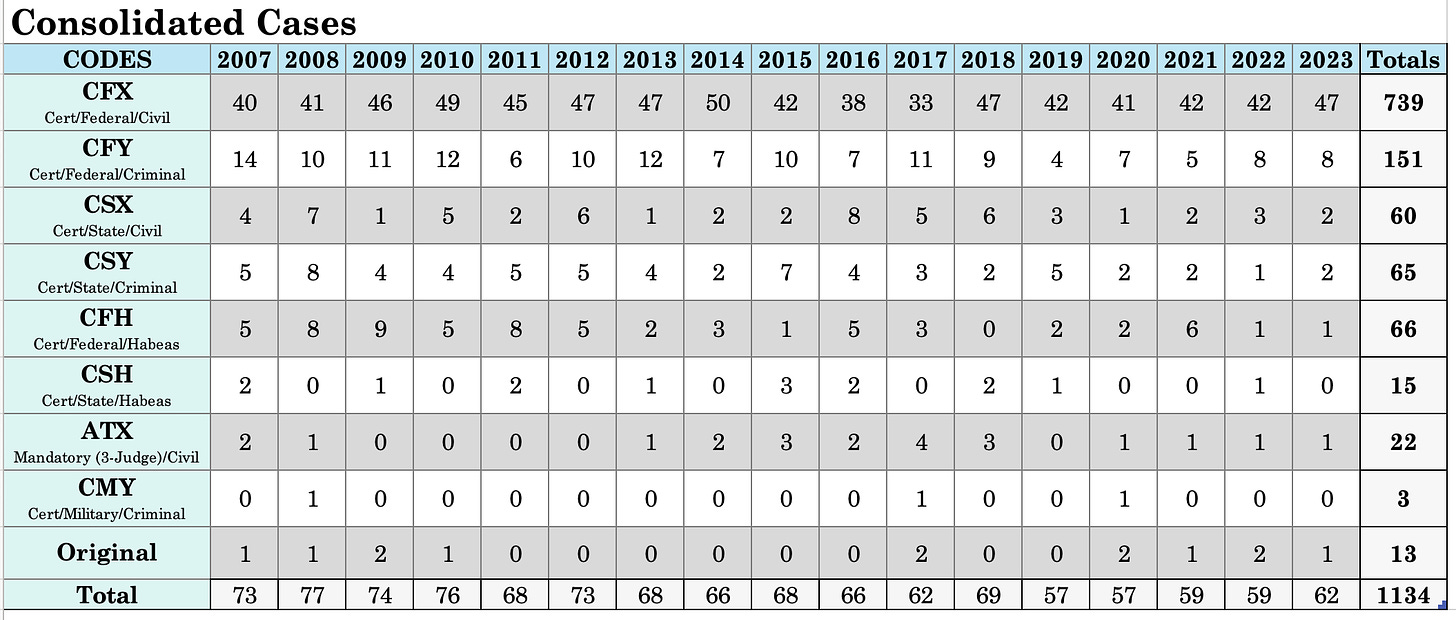

One of the things you’ll notice from those lists is that the Court has a three-letter system for categorizing every case over which it exercises appellate jurisdiction. The first letter (C/A/Q) tells us whether the case is there via certiorari; via mandatory appeal (from a three-judge district court); or on a question certified by a federal court of appeals (which hasn’t happened since 1981—see the trivia, below). The middle letter tells us what kind of court the case came from (Federal Appeals Court / State Court / Three-Judge District Court / Military / Other). And the last letter tells us whether the case is civil (X); criminal (Y); or habeas or some other collateral attack on a conviction (H). So Bouarfa, for example, would be coded “CFX.”

Focusing on cases coded “CSY” will thus cover the precise dataset we’re looking for: cases in which the Supreme Court is hearing a direct appeal from a state criminal conviction. To that end, here’s a chart that one of my superstar RAs, Alyssa Negvesky, put together collating the case-code data for every term going back to OT2007:

There are a couple of interesting conclusions to draw from the data:

First, the dominant source of cases on the Court’s docket—federal civil appeals (“CFX”)—has remained fairly constant over the 17 years’ worth of data. Thus, even as the Court’s total number of cases has shrunk from the low 80s to the mid-60s, the fall-off hasn’t been there. Second, the categories with visible fall-offs include federal criminal appeals (CFY); state criminal appeals (CSY); and federal habeas petitions (CFH), although the Court’s data doesn’t distinguish between habeas petitions from state prisoners and those from federal prisoners. And third, with regard to state criminal appeals, the fall-off has been to near zero (and, so far this term, actually zero).1

And one point not reflected in this data, but which Alyssa and I are working on providing additional support for, is that the direct criminal appeals the Court is taking, both from lower federal courts and state courts, tend to be focused more on substantive questions than on criminal procedure. Just to take one anecdotal example, for OT2022, of the eight “CFY” cases (federal criminal appeals), only one (Samia) involved a question of constitutional criminal procedure. And the lone “CSY” case from OT2022, Counterman v. Colorado, involved a substantive First Amendment challenge to the statute of conviction—not a criminal procedure issue.

To draw a quick and unscientific contrast, consider the Supreme Court’s docket 10, 20, and 30 years ago (I’ll use OT2023 for this comparison because it’s the last term for which we have full data). In OT2013, the Court heard four direct appeals from state criminal convictions, all of which raised criminal procedure issues. In OT2003, the Court heard nine direct appeals from state criminal convictions, eight of which raised criminal procedure issues. And in OT1993, the Court heard seven direct appeals from state criminal convictions, six of which raised criminal procedure issues. We’re working on more comprehensive charting of all of these categories, but there’s no immediate reason to believe that any of these terms are outliers.

Thus, we can make two statements with a fair degree of confidence: First, direct appeals from state criminal convictions are disappearing from the Supreme Court’s docket. Second, that decline (and the broader decline in the Court’s criminal procedure docket) is is a relatively recent phenomenon, with the most dramatic effects over the last 7-8 years.

Why This Matters: The Importance of Establishing Law

I’ll leave for another day the question of why the Court has become less interested in direct appeals from state criminal convictions and/or criminal procedure issues. (I’ll just flag for now that I don’t think that a fall-off in the total number of petitions explains it.) Because whatever the cause of this trend, there are at least three related but distinct consequences that ought to be considered.

First, with regard to state criminal defendants themselves, the downward trend is doubly problematic. Not only does this mean that a vanishingly small number of criminal appeals from state courts are getting the justices’ attention, but since Congress enacted the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA), federal district courts considering habeas petitions attacking state criminal convictions are required to give substantial deference to the state court’s constitutional analysis. Thus, since 1996, the Supreme Court has become the only federal court in a position to provide de novo review of constitutional claims on which state prisoners lost at trial. One would think that this shift would put pressure on the justices to take more direct appeals from state criminal convictions—or, at the very least, more direct appeals from state post-conviction proceedings. In fact, the opposite has happened. In the process, direct appellate review of a state criminal conviction has gone from being a long-shot to being a no-shot—when it’s arguably more important than ever.

Second, because of AEDPA (and, it should be said, of how the Supreme Court has interpreted AEDPA), direct appeals from state courts, whether from a conviction or from a state post-conviction proceeding, are just about the only way in which the Supreme Court can clarify the constitutional rules in state criminal cases in a way that will apply to future cases. That’s because AEDPA bars relief on claims that were adjudicated in state court unless the state court decision “was contrary to, or involved an unreasonable application of, clearly established Federal law, as determined by the Supreme Court of the United States.”

What that means in practice is that federal courts hearing habeas petitions challenging state convictions, including the Supreme Court, can’t grant relief unless the law is already clear. And the Supreme Court held in 2000 that only the Court’s decisions, and not its dicta, can “clearly establish” constitutional rules enforceable under AEDPA. After AEDPA, a state criminal defendant, to prevail on appeal, need only show that the state court was wrong. A state criminal defendant, to prevail in a federal habeas petition, needs to show that the state court acted in flagrant disregard of an existing Supreme Court precedent. It is not logically possible, in the second class of cases, to make new law—even if the state court did act in flagrant disregard of an existing Supreme Court precedent. The best a court could say in such a case is that the law was already clear, and the state court mucked it up.

Third, damages suits against government officers have also come to depend upon “clearly established” law—thanks to the Supreme Court’s modern qualified immunity jurisprudence. Under that jurisprudence, to prevail in a damages suit against most government officers, the plaintiff must show both that (1) the officer violated their rights; and (2) at the time of the violation, it was clearly established that the officer’s conduct was unconstitutional. (The plaintiff has to prevail on both questions to “win.”)

Thus, if the unconstitutionality of the officer’s conduct wasn’t “clearly established” at the time it took place, then courts have an incentive to rule for the officer without deciding whether, going forward, their conduct actually did cross the line. The Supreme Court tried to account for this in 2001, holding that, in qualified immunity cases, federal courts always needed to answer both questions—so that, even if the officer won on uncertainty today, the law would be settled for the future. But the justices unanimously back-tracked from that requirement in 2009—and have since poured even more cold-water on courts providing forward-looking guidance in cases in which the law wasn’t clearly established at the time of the alleged violation. What all of this means is that it is virtually impossible today to establish new constitutional rules (or clarify old ones) in damages suits, too.

If damages suits aren’t a vehicle for clarifying the scope of our constitutional rights, then all that’s left is injunctive relief or direct appeals from criminal cases raising the same constitutional questions. Injunctive relief quite obviously can establish forward-looking principles of constitutional law. But most constitutional violations are brief—and are thus not appropriate for prospective relief. That’s especially true in the context of the kinds of constitutional claims that tend to come up in criminal cases—because they’re either about things that happened before the trial or things that happened during the trial. That increasingly leaves direct appeals in criminal cases and from state post-conviction proceedings as the only way to clarify the scope of the Constitution when it comes to an array of our individual rights. The fewer such cases that the Court is hearing and deciding, the more those rights will remain unclarified.

Nor is it a response to suggest that there just aren’t an array of important and unsettled questions of constitutional criminal procedure currently percolating through lower courts. From the relationship between biometrics and the Self-Incrimination Clause to how “geofence” warrants square with the Fourth Amendment to continuing debates over the scope of the Sixth Amendment’s Confrontation Clause, and beyond, there is a veritable slew of unanswered constitutional questions on which the Supreme Court’s guidance would presumably be quite useful. Folks will have their own views as to which disputes are more worthy of certiorari or less, but any argument that there aren’t suitable cases out there is belied by plenty of contrary examples.

Of course, some may read this and think that we’re better off having the current Supreme Court stay out of these issues than dive into them. I understand where that impulse comes from, but I rather vehemently disagree. First, at least some criminal procedure issues have a way of not sorting the justices into their normal ideological camps. Second, even for those that do, the Court affirmatively articulating a rule that is widely deemed to be insufficient is far more likely to galvanize a public and/or legislative response than the Court simply leaving the law unsettled. And even if it didn’t, I’d still think we would all be better off knowing what the law is than living in a state of uncertainty—because in a day and age in which uncertainty uniformly means that the government wins, it’s hard to see how we’d be that much worse off if the Court provided more clarity. It also ought to follow that there would be salutary effects for the government and its officers as well if it were clearer where the relevant constitutional lines were—and weren’t.

I don’t mean to overstate the point; the Court can, quite obviously, clarify constitutional rules in federal criminal appeals—which continue to represent the second-largest set of cases on the Court’s docket. But (1) that subset is also declining, both in absolute numbers and with respect to how many of the cases involve criminal procedure questions; and (2) federal criminal prosecutions, for an array of reasons, just don’t tend to raise the same array of constitutional questions that prosecutions from the 50 states do. Federal courts aren’t immune from constitutional errors, but for a host of reasons, more errors of more distinct types are likely to be made in different state courts.

In all, then, the more that direct appeals from state criminal convictions are disappearing, and have disappeared, from the Court’s docket, the less forward-looking constitutional law the justices will make—especially when it comes to those constitutional rights most directly related to law enforcement interactions and the criminal justice system. I don’t imagine for a second that this is why direct appeals from state criminal convictions have all-but disappeared from the Supreme Court’s docket. But it is, at least in my view, reason enough for why they should not have disappeared—and why it is and ought to be incumbent upon the justices to take more of these cases in the years to come.

SCOTUS Trivia: The Last QFX Case

I’ve briefly alluded before to the last time that the Supreme Court accepted a “certified question” from a federal court of appeals under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(2)—in 1981, right after the Court’s expedited (and controversial) ruling in the Iranian hostage agreement case, Dames & Moore v. Regan. In Iran National Airlines Corp. v. The Marschalk Co., the Second Circuit had certified three questions to the Supreme Court concerning how Dames & Moore applied to a dispute with related but distinct facts. Here’s the Supreme Court’s answer:

Justice Powell, joined by Justices Marshall and Stevens, dissented—arguing that the Court should simply have vacated the Second Circuit’s ruling and remanded in light of Dames & Moore—rather than answer abstract questions without full briefing and argument. Perhaps that dissent stuck, because the Court’s jurisdiction to accept certified questions has effectively become moribund since then—despite several high-profile (and, in my view, compelling) attempts to invoke it in the 2000s. Even counting Marschalk, the Court has answered certified questions only four times since 1946.

Until and unless Congress requires the Court to accept certified questions from lower courts (a variation on which is one of my favorite proposals for expanding the Court’s docket), it’s hard to imagine any more “QFX” cases (let alone “QFY”) anytime soon.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone next week.

Until then, have a great week!

As of Friday, the Court has granted certiorari to review three decisions from state courts. The Court categorizes all three as civil appeals. And although I think a fairer characterization of Glossip v. Oklahoma is as a post-conviction review proceeding (so, CSH instead of CSX), it is most definitely not a direct appeal of a criminal conviction.

I enjoy these deep dives into the Court’s docket. I always learn something.

I am a criminal defense appellate attorney and I found this a very interesting article.

Does your data show any change in which party is seeking cert? You may have touched on this somewhat in the article, but with the Court's composition being what it is, there is little expectation that in most cases, Supreme Court taking the case would benefit your client. And unlike the Government (or its state vis-a-vis), individual practitioners cannot prioritize institutional interests over the best interests of the client.

It is also great that you mentioned the Suipreme Court's AEDPA jurisprudence. It has read the statute, I think, far broader than originally billed and it more or less wrote fed habeas relief out of existence (unless you have a rare case where you can convince the federal habeas court that there is no state merits adjudication to defer to). And it also pushes anything that smells like a new issue into the direct appeal / cert scenario. And if those aren't granted either, there is little recourse for the defendants.