111. Ex parte Milligan and the Limits of Martial Law

Although it was later narrowed, the Supreme Court's 1866 repudiation of Civil War-era military commissions remains a bulwark against military authority wherever civilian courts are functioning

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current work, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

I thought I’d take a break from all of the current events coverage in the last few weeks and use this week’s “Long Read” for a bit of a more historical take—this one looking back at the Supreme Court’s landmark, if often misunderstood, 1866 ruling in Ex parte Milligan. In Milligan, a Supreme Court with a majority of justices appointed by President Lincoln unanimously rejected military commissions that Lincoln had convened during the Civil War to try criminal offenses by Confederate sympathizers in some parts of the North—in a ruling that was handed down in April 1866, although the written opinions weren’t filed until that December. As noted below, the Supreme Court narrowed Milligan in some meaningful (and highly controversial) ways in its 1942 ruling in Ex parte Quirin (the Nazi saboteurs’ case). Nevertheless, Milligan’s rousing repudiation of military rule anywhere in which civilian courts are open and functioning remains a vital constitutional bulwark today—one that hopefully will never be put to the test.

But first, the news.

On the Docket

As might be expected for Thanksgiving week, the Court didn’t make a lot of news. Last Monday’s regular Order List included no new grants of certiorari. And the only separate writing respecting a denial was a statement from Justice Sotomayor in Baker v. City of McKinney, joined by Justice Gorsuch, about whether, when government officers damage private property while exercising police powers, that damage constitutes a taking of property requiring “just compensation” under the Fifth Amendment. The brief opinion emphasized that this is “an important and complex question that would benefit from further percolation in the lower courts prior to this Court’s intervention.”

Turning to this week, we do not expect an Order List at 9:30 ET today (the justices didn’t hold a Conference last week). But the Court’s December argument session begins at 10 ET with a pair of arguments today—and with the much-anticipated argument in Skrmetti (on the constitutionality of Tennessee’s ban on certain gender-affirming medical care for transgender adolescents) set for Wednesday. Over at “Law Dork,” Chris Geidner helpfully puts into broader context the arguments—and the stakes—in the first major transgender discrimination case to reach the justices on the merits.

We don’t expect any decisions in argued cases this week, so the only formal orders, if any, would come on pending emergency applications and maybe new grants of certiorari on Friday. The next regular Order List isn’t expected until 9:30 ET next Monday, December 9.

The One First “Long Read”: The Milligan Precedent

Ex parte Milligan may hold the distinction of being the most obscure Supreme Court decision to make it into the pop culture zeitgeist. It comes up in at least two different episodes of Law & Order (“you’re lucky that the Second Circuit didn’t nail the writ to your forehead,” Adam says in one of them); it gets a brief discussion in the 1998 movie, The Siege; and it otherwise comes up every so often for its brief—but still deeply relevant—discussion of the limits on martial law. Indeed, Milligan may well own the title of the Supreme Court’s first major civil liberties ruling in its history. And it was a dandy.

At its core, Milligan was about one set of military commissions that the Lincoln administration used during the Civil War to try a handful of suspected Confederate sympathizers in the North. To be sure, the Union Army also used military commissions in areas in which there was no functioning civil government, but those raised different questions from the ones at issue in Milligan—which were used in parts of the country in which civil authority was very much in place, even if, as was true in southern Indiana, it was somewhat hostile to the federal government.1

At the time, perhaps the most well known of the military commission prosecutions was the 1863 trial of Clement Vallandigham—the de facto leader of the “Peace Democrats,” known by their critics as “Copperheads.” Vallandigham was tried by a military commission in Ohio for inflammatory speeches he gave sharply criticizing the war. He was convicted and sentenced to exile to the Confederacy. And although he attempted to get the U.S. Supreme Court to review the conviction, the Court would hold, in February 1864, that it lacked the power to hear any appeal from Vallandigham’s military commission.

Lambdin Milligan was not the national political figure that Vallandigham was. Instead, he was one of ten defendants in what were known as the “Indianapolis treason trials” of 1864—in which the federal government tried by a military commission, rather than a civilian court, Confederate sympathizers who were accused of having stockpiled weapons as part of a suspected plot to attack state and federal authorities, including a possible raid on (and attempt to liberate) a nearby Confederate POW camp. One escaped to Canada and was found guilty (and sentenced to death) in absentia. Five others agreed to testify against the remaining defendants in exchange for the charged being dropped. That left Milligan and three co-defendants, who were found guilty in late 1864. Milligan and two others (William A. Bowles and Stephen Horsey) were sentenced to death; Andrew Humphreys was sentenced to hard labor.

In May 1865, shortly after President Johnson commuted the death sentences to life imprisonment, lawyers filed habeas petitions on behalf of Milligan, Bowles, and Horsey, in the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Indiana. There, the local district judge and the Circuit Justice, David Davis, agreed to “divide” in order to create grounds for an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. The justices heard seven days of oral arguments in March 1866 from a phalanx of leading lawyers—including Congressman (and future President) James A. Garfield on Milligan’s behalf. On April 3, just before the end of the December 1865 Term, Chief Justice Chase announced from the bench that the Court had concluded that the military commission lacked jurisdiction to try the three defendants—and that they should therefore be released. The opinions respecting that ruling would come down shortly after the Court’s December 1866 Term began—on December 17.

For a five-justice majority, Justice Davis held that the central constitutional problem with the military commissions was that they violated the defendants’ right to a trial by jury under the Sixth Amendment—a holding that also called into serious (if not fatal) question the military commission that had been convened to try (and had convicted and sentenced to death) eight of the Lincoln assassination conspirators. More fundamentally, Davis wrote, the problem with the government’s resort to military process was that, at the time of the military commission, civilian courts in Indiana were fully functioning. In Davis’s words, military authority

can never be applied to citizens in states which have upheld the authority of the government, and where the courts are open and their process unobstructed. This court has judicial knowledge that in Indiana the Federal authority was always unopposed, and its courts always open to hear criminal accusations and redress grievances; and no usage of war could sanction a military trial there for any offence whatever of a citizen in civil life, in nowise connected with the military service.

In other words, the right to jury trial was a bulwark against military prosecutions even during wartime—at least for those with no formal connection to the military. Martial law might be an exception in those areas in which it was properly in effect, but that couldn’t—and didn’t—include places in which civilian courts were open and functioning.

In a separate opinion on behalf of four justices (which was very unusual at the time), Chief Justice Chase rested his conclusion on a far narrower ground—not that military commissions were always unconstitutional, but that their defect in the Civil War-era context was Congress’s failure to expressly authorize them. (“Congress had power, though not exercised, to authorize the military commission which was held in Indiana.”) Thus, whereas the majority focused on the individual liberties of the defendants; the theme of the concurrence was the proper separation of powers.

I’ve written before about how the Court narrowed Milligan somewhat in 1942—when it upheld, in Ex parte Quirin, the military commission prosecution of Nazi saboteurs who had surreptitiously entered the United States, even though the civilian courts were open and functioning. Critically, Quirin purported to distinguish Milligan on two grounds—that Congress had authorized the saboteurs’ commission; and that, in any event, there was an exception to the Sixth Amendment for “offenses committed by enemy belligerents against the laws of war.” Although both of these grounds were highly dubious, they also reinforce how much of Milligan remains good law today—especially since, in 2006, the Supreme Court in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld invalidated the first generation of post-September 11 military commissions at Guantánamo on the ground that they went further than what Quirin had sanctioned.

To be sure, Hamdan doesn’t settle how far Congress can go to authorize military trials in contexts other than the one presented in Quirin; it held only that Quirin was the outer bounds under the laws then in effect. But it seems worth emphasizing that the D.C. Circuit’s post-Hamdan jurisprudence under the Military Commissions Act has twisted itself into a pretzel to avoid recognizing much more—and even then, only because the defendants were non-citizens held outside the territorial United States. Milligan thus remains today a forceful precedent for the idea that civilians in the United States are entitled to civilian criminal prosecutions, rather than military trials, so long as the civilian courts are functioning.

One can hope that we never find out just how forceful a precedent it is.

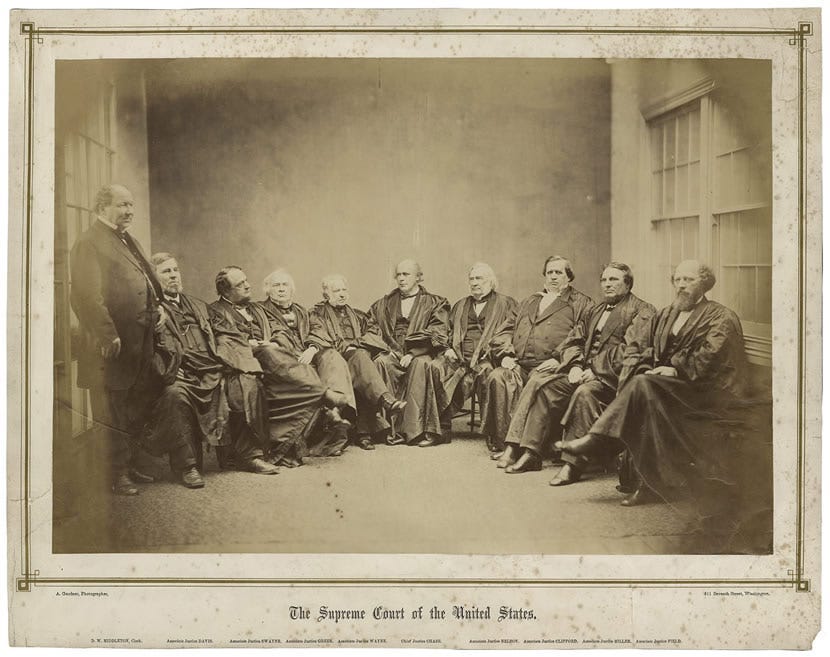

SCOTUS Trivia: The First Class Photo

The image accompanying today’s post is a digital reproduction of the first of its kind—the very first time that the Supreme Court’s justices all sat together for a group photograph. (It just happened to be the same justices who had recently decided Milligan, hence my choice to use it for today’s post.)2

As the Supreme Court’s website explains (through a wonderful digital collection maintained by the Court’s Curator),

On February 23, 1867, the Supreme Court Justices made their way to Alexander Gardner’s Photographic Gallery at Seventh and D Streets, N.W., in downtown Washington, D.C. to pose for a group portrait for the first time. Soon afterward a local newspaper, probably repeating Gardner’s own wording, described it as showing “. . . the Supreme Court ‘on the bench,’ costumed in the ‘robes of office,’ with the clerk of the court in attendance in citizen’s dress.” This is the only time the Justices have ever been joined by anyone else for such a photograph.

Over time, the “Class Photo” has become one of the Court’s more visible traditions. Since 1894, the justices have sat/stood in the same seniority order. Since the early 1900s, a new picture has been taken at least once in a year in which a new justice has joined the Court. Since 1930, the justices have appeared in front of velvet drapery. Since 1941, the picture has been taken in the Court’s own facilities. Since 1965, the picture has been in color. And since 2017 (and this is my favorite), the picture isn’t even a single picture; it’s a composite. Each justice gets to pick their favorite image of themselves from a series of group shots taken by the Court’s photographer—which, for lack of a better verb, get photoshopped into a single, public graphic that at least appears to be a single image:

It turns out that even the (seemingly) most straightforward things about the Supreme Court have complicated stories, traditions, norms, and carefully choreographed choices behind them.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone next week.

I hope that you all have a great week!

The Supreme Court has specifically upheld the use of military tribunals to try civilian offenses in areas under military occupation (in which there is no functioning civilian government), most recently with respect to post-World War II Germany.

In between March and April 1866 (when Milligan was argued and the initial judgment was handed down) and December 1866 and February 1867 (when the opinions came down and the class photo was taken), Congress had dramatically reduced the size of the Court—eliminating the then-extant (and vacant) tenth seat, and providing that two more seats would be eliminated if and when they became vacant—all to prevent President Johnson from appointing any justices. But no vacancy had yet occurred—hence why the first photo has what we today think of as the "full complement” of nine justices.

I had no idea the class photo is photoshopped. Why on Earth is Alito grimacing like that then, were his eyes closed in all the other shots?

Most of the justices look like they've had a few and are quite goofy.