109. Things Fall Apart

Some reflections on my disheartening exchange with Judge Jones at last Thursday's Federalist Society convention—and its ominous implications for the future of legal debate

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Usually, the Monday issue of this newsletter is devoted to a brief recap of the previous week of Supreme Court news; a longer-form discussion of some recent or historical development at the Court; and some trivia to end on a more-frivolous note. But because the Supreme Court didn’t make a lot of news last week; and I, somehow, did, I thought I’d use today’s issue instead to reflect on what happened at last Thursday’s Federalist Society national convention—in particular, my exchanges with Fifth Circuit Judge Edith Jones on the topic of “judge shopping” (or, more specifically, her sustained personal attack against me for my criticisms of that behavior, including her allegation that I am directly responsible for death threats she claims Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk, the Amarillo-based federal district judge who has been a frequent favorite of judge-shoppers, has received).

There is quite a lot to unpack here (and I’ll take a stab at much of it), but to skip to the punchline, my two big takeaways are that (1) the inability of people who should know better to distinguish between principled criticisms of judicial behavior and personal attacks on judges is a serious problem for our discourse; and (2) given the period of unified Republican control of the federal government into which we’re heading, without real effort on the part of judges to publicly acknowledge both the existence of this distinction and the importance of principled debate over judicial behavior, we’re going to exacerbate—perhaps past the breaking point—the (already) intensely partisan divide over how much power unelected federal judges should have in the first place. In both of these respects, what happened Thursday was both a sad reflection of where we are and an ominous warning of where we may be going.

I. What Happened

Not only are eyewitness recollections themselves suspect, but I am quite obviously an interested party in relaying the details of Thursday’s events. So before even doing that, let me note that there is a public video of the entire panel—which folks can watch for themselves. My remarks begin at 41:30; Judge Jones begins at 50:23; and things ran off whatever rails were remaining around 1:12:50:

The video really speaks for itself. But in case you don’t have time to watch, or you’d like additional context, here’s how things went down from my perspective:

On September 30, I received an invitation from Dean Reuter, Senior VP and General Counsel of the Federalist Society, to participate in Thursday’s panel. Dean didn’t tell me who else would be on the panel (and, in fairness, I didn’t ask). But given my own writings (especially in this newsletter) on the relationship between court- (and Court-)reform discussions and judicial independence, it seemed to me that mine might be a perspective not otherwise represented on such a panel. (I’ll have more to say about the ongoing debate over whether people like me should ever participate in Fed Soc events below.)

I found out roughly two weeks later that the rest of the panel would feature Judge Jim Ho (as “moderator,” more on that in a moment); Wash. U. law professor Dan Epps; Judge Jones; and Paul Weiss partner (and noted Supreme Court advocate) Kannon Shanmugam. I’ll note that I was a bit surprised that a sitting circuit judge would be on the panel, and not just moderating it, but c’est la vie.

We had a planning call for the panel on November 4—on which Judge Ho said he was “only” going to moderate the panel; and Kannon, Dan, and I each described in broad strokes what we were planning to discuss (in ways that closely mirrored what we actually said on Thursday). Judge Jones mentioned that she was planning to talk about the “problem” of courts responding to political pressure, and flagged the Judicial Conference’s March 2024 proposal to curb judge-shopping (in response to which she had already been quoted in several media accounts) as one of the examples. Suffice it to say, putting me in the spotlight was … not discussed.

Fast-forward to the panel. After Judge Ho gave his own five-minute opening statement (on the prep call, he had said that he was planning only to introduce us), Kannon, Dan, and I each delivered a version of the opening remarks that we’d described on the pre-call (my remarks largely paralleled what I wrote about in last Thursday’s bonus issue). And then it was Judge Jones’s turn.

In fairness, Judge Jones did make the main point she had outlined in advance—that judicial independence is threatened when courts respond to public criticisms, mixed in with a complaint that part of the problem is that the academy and the bar aren’t doing enough to “stand up” to these criticisms—and that that’s why she was taking this opportunity to “speak up.” If that’s where things had ended, I would’ve thought that most of what Judge Jones had said was, at least, an intellectually defensible view—even if it’s one with which I disagreed.

But along the way, Judge Jones made it very personal—and about me, specifically. It started by putting words into my mouth (claiming that I’ve accused litigants and judges of “close-to unethical” behavior—which I never have) and accusing me of hypocrisy in criticizing the practice of litigants steering cases to single-judge divisions in Texas in order to ensure that a specific judge is assigned to hear their case (a practice in which the State of Texas has publicly admitted it is engaging). As Jones pointed out, I never accused the (liberal) Judge William Wayne Justice of similar behavior (never mind that Judge Justice was appointed to the federal bench 11 years before I was born). The basic argument she seemed to be making was that this behavior doesn’t just happen with Republican-appointed district judges in Texas—although it’s not clear to me why, even if that’s true, it’s a defense of the practice, as such.

In all, by the end of her opening remarks, Judge Jones’s central evidence for her claim that the Judicial Conference had responded to unfair and unfounded attacks on judge-shopping was that I’m a hypocrite. Several of her factual claims in support of that assertion were just wrong. For instance, she went out of her way to claim that the Department of Justice hasn’t sought to change venue in any of the cases filed against the Biden administration in single-judge divisions in Texas—which, in her view, showed why my critiques aren’t even shared by the parties on the receiving end of this behavior. In fact, DOJ most certainly did move to transfer at least three cases (their motion to transfer in one of the Amarillo cases provoked another clumsy shot at me—by Judge Kacsmaryk himself). But what these errors really underscore is how much she wasn’t using me as a foil for one side of the “debate”; I was her primary target, as such.

At that point, each of the panelists was given a chance to respond. Kannon went first and offered some modest responses to Dan and me. When it was my turn, I briefly responded to Kannon before turning to Judge Jones. The crux of my response was to discuss the example of judge-shopping in patent cases—where there was broad consensus from across the political spectrum that it made the legal system look pretty bad when 23% of patent cases nationwide were being filed in Texas’s 23rd-largest city. (This was basically a shortened version of my written response to a speech by Judge Reed O’Connor.) If folks like Senator Thom Tillis (R-N.C.) and Chief Justice John Roberts (and the Western District of Texas, which changed its case-assignment rules in response) could agree that judge-shopping was a problem in that context, I suggested, that sure seems to support the conclusion that it’s a problem unrelated to the partisan / ideological affiliations of the parties and the judges. And I specifically disclaimed that I had personally attacked any of the judges to whom cases are being shopped.

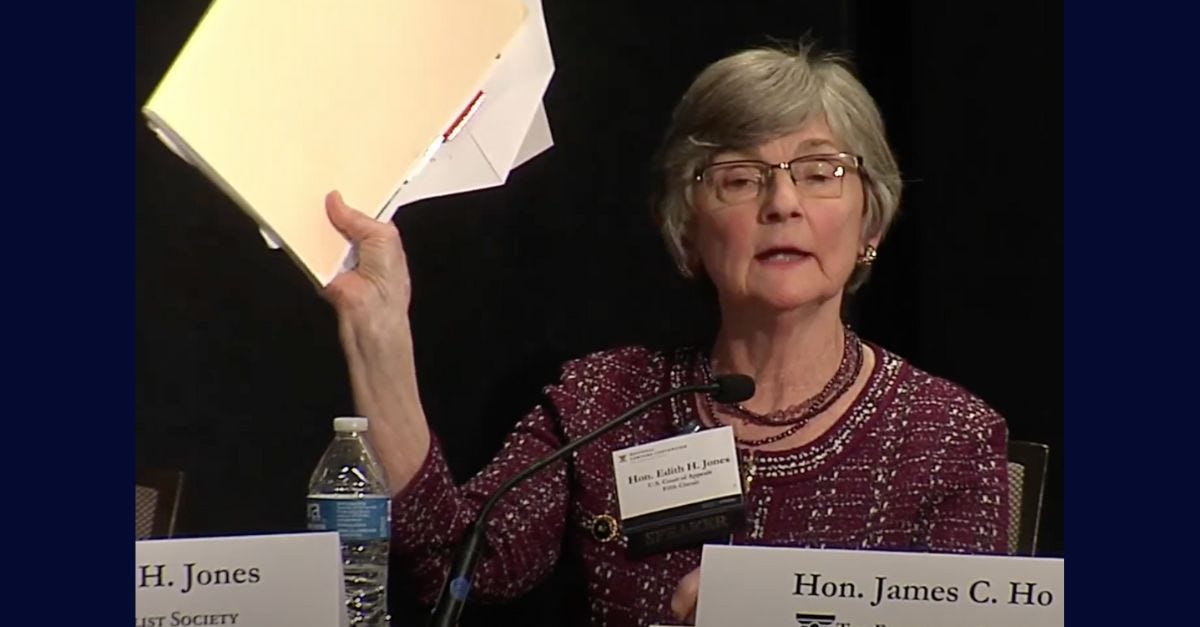

Then it got (even more) awkward. Judge Jones didn’t respond at all to my patent example—even though it seems to provide rather powerful evidence that the debate over judge-shopping is not a partisan one. Instead, apparently having been waiting for me to disavow such attacks, Judge Jones pulled out a manila folder that she claimed was full of my blog posts, tweets, amicus briefs, and other writings on the subject (honestly, given how much work I’ve done in the field, it seemed pretty thin). And she proceeded to read out individual tweets (that one of her law clerk presumably found, printed out, and highlighted—I leave to others whether that’s an appropriate use of federal judicial resources) as evidence of how I have been “personally attacking” the judges in these cases, and had engaged in a series of “ad hominems,” with the purpose, she claimed, of intimidating these judges. This wasn’t off the cuff; it was a set-up.

Leaving aside how bizarre (and, it should be said, non-responsive) this maneuver was, it was also, in my view, hilariously ineffective; each of the examples Judge Jones read of my supposedly “unsavory” attacks were … not? Instead, they were anodyne descriptions of either litigants’ behavior; the factual results of filing in those divisions; or, in what appears to have been my worst sin, descriptions of some of these judges as being “right-of-center” (or, in one of her examples, further to the right than many of the Democratic appointees on the Northern District of California are to the left).1 Over and over again, Judge Jones attempted to portray my own words as casting aspersions on these judges—saying, at one point, “if that’s not a personal attack, I don’t know what is.” Indeed.

In perhaps the most ominous moment of the session, she then insisted that I was directly responsible for death threats that she claims Judge Kacsmaryk (and his family) has received. If Judge Kacsmaryk has indeed received such threats, that is gravely concerning (and illegal, if within the scope of the true threats doctrine). But it ought not to be a controversial view that federal judges should not be publicly blaming individual critics for provoking those threats without even attempting to connect the dots from the critics’ arguments to such threatening behavior.

Readers can and should judge for themselves from the video; I thought that I did a pretty good job of not taking the bait and of maintaining a pretty even keel throughout the exchange.2 At one point, I suggested that Judge Jones and I ought to grab a beer and hash out our differences. At another, I suggested that perhaps Judge Jones and I simply have a different understanding of what a “personal attack” actually is (and that I doubted that she would count her own remarks as one). Finally, I expressed my disappointment that, rather than having a substantive debate about judicial independence (which was supposed to be our topic), or even about judge-shopping, specifically (Judge Jones’s focus), we were doing … whatever that was. I said something to the effect of “This isn’t the kind of debate that I thought the Federalist Society was interested in sponsoring and I’m disappointed in the conversation that we’ve had today.” Judge Jones responded by asserting that “this is not an ad hominem . . .,” and then proceeded to go after me (and my motives) again.

Ironically, on the judicial independence point, Judge Jones’s behavior, if anything, helped to reinforce one of the central claims I tried to advance in my prepared remarks: that the more judges equate judicial independence with insulation from any reforms or criticisms, the more they’re losing sight of why the Constitution enshrines judicial independence—not as an end unto itself, but to ensure that courts can serve their role in our system of checks and balances. We didn’t trade tyrannies of the majority for a tyranny of unelected judges; the interbranch dialogue, debates, and compromises are supposed to matter. Insofar as Judge Jones’s argument was that my criticisms are a threat to judicial independence, I fear that she only helped to make my point.

As if all of that wasn’t weird/sad enough, when we turned to audience Q&A, the panel ended with a (clearly staged) spectacle—in which 97-year-old Federal Circuit Judge Pauline Newman, who Judge Jones had told Judge Ho to call upon before she had even stood up, described her plight (she has been suspended from hearing new cases by her colleagues over claims of age-related judicial disability—for which she is currently suing them), and asked what it portends for judicial independence. If I’d had a chance to respond, I might have noted that the whole point of the procedures created by the Judicial Conduct and Disability Act of 1980 is that Congress has left it to Judge Newman’s fellow independent judges to resolve her fate. There are definitely issues that can arise from judges policing themselves, but judicial independence … isn’t one of them. I didn’t get the chance to say anything, though; Judge Jones had a canned (and sympathetic) answer at the ready.

Like the contents of Judge Jones’s manila folder, we were just props.

II. The Reaction in the Room

In retrospect, the thing that strikes me the most about how things went down was the reaction in the room. Judge Ho (who, remember, was the “moderator”) intervened at one point only to make an awkward attempt at a joke about why I’d left Texas.3 To Dan’s significant credit, he objected to, and was quite critical of, the personal tenor of the conversation (more on his central point below). Meanwhile, the visible/audible audience reaction was decidedly to the contrary. Not only did folks loudly applaud Judge Jones, but even when I appealed to the Federalist Society’s purported commitment to principled debate, the best I got was a smattering of applause—and a handful of boos. Some commitment.

To be sure, a bunch of people came up to me afterwards (and even more e-mailed, texted, or DM’d me later as the news and the video began to spread) with words of encouragement and support. And I’m grateful for that—and for them. But it’s worth thinking about what would’ve happened and what message would have been sent if Judge Ho (who, last I checked, also has an Article III commission protecting him), or any of the folks who came to the microphone during the Q&A, had stood up for me—or even for the idea that we should be debating the underlying topic on substantive terms. Whether or not silence in these circumstances is complicity, applause surely is.

III. Personal Attacks vs. Substantive Criticisms

More fundamentally, my broader reaction to Thursday is how much we’ve lost the thread on the difference between personal attacks and substantive criticisms, especially where judges/courts are concerned. To be sure, I claim no special expertise about where the line between those two things is, and I recognize that different people may draw it in different places. But it seems to me that there are some general principles that ought to be uncontroversial:

First, and this was Dan’s central point toward the end of the panel, whether or not a critic is making a personal attack has no bearing on the accuracy of their critique (this is the “Ad Hominem Fallacy”). People will have different motives for why they do/say things; the question is whether there is truth to what they are saying. Perhaps you’ll be less inclined to believe someone whose motives you suspect, but that only matters if their claim is in any way tied to their subjective beliefs. If someone who you distrust provides you with incontrovertible data that speak to a specific conclusion, then that conclusion is valid regardless of why the person has offered it. Thus, even if Judge Jones had pulled out of her manila folder actual evidence of me personally attacking judges,4 it wouldn’t have proven anything about whether judge-shopping (1) is a problem; or (2) raises questions about public faith in the integrity of the judiciary—the only way I could envision even trying to tie that topic to the putative theme of Thursday’s panel. Personal attacks are unfortunate (for reasons amply demonstrated by Thursday’s events), but they’re also counterproductive because, even when they succeed, they don’t per se establish any substantive points about the underlying topic of debate.

Second, and to that point, especially in this day and age, describing a judge by reference to the President who appointed them and/or their rough orientation relative to our contemporary political/ideological spectrum should just not be viewed as a “personal attack.” Consider this sentence:

“Judge Smith is a Democratic appointee who was named to the bench by President Whitmore, and whose rulings in ideologically charged cases have tended to favor left-leaning parties.”

My own view is that nothing in this statement is a personal attack—even if the claim about Judge Smith’s rulings is actually incorrect. People can be wrong in their criticisms of judges without being personal. And making a claim about a pattern in a judge’s rulings is, quite pointedly, not imputing a nefarious motive to the judge; it’s suggesting that, for whatever reason, their rulings are following a particular pattern. (Indeed, this is why, for the umpteenth time, it’s so important that judges explain their rulings—to provide the basis for a response to claims such as those.) Whether or not judges (and justices) in general ought to have thicker skin, they should at least understand the difference between a critique that argues that a ruling of theirs is substantively wrong and one that accuses them of ruling that way for non-judicial reasons or otherwise impugns their integrity. Plenty of judges with integrity get things wrong; one doesn’t follow from the other.

Third, and finally, in a world in which personal attacks are (rightly) disfavored, the inability of prominent public figures to meaningfully distinguish between them and substantive criticisms poses serious risks of both ignoring problems raised by those with whom you tend to disagree; and chilling folks from speaking out out of fear that they, too, will be attacked for crossing the substantive/personal line. To be sure, the latter concern isn’t one that I experience personally. In addition to the thick skin that comes from having grown up between two brilliant, assertive sisters, I’m a highly visible, tenured, white male professor at a private university in a very blue jurisdiction; I’m about as safe from professional retribution as anyone (other than Article III judges, anyway) can be. But for folks who don’t have the same formal and practical protections that I do, this latter concern is (and ought to be) a serious one. Folks like Judge Jones should be encouraging principled disagreement, not using forums like Thursday’s to seek to silence, embarrass, or otherwise cow into submission those who were invited to provide it. That it failed in this case doesn’t mean it won’t succeed next time.

IV. Progressive Academics and the Federalist Society

Other than the (to my count, five) public comments I’ve seen in defense of Judge Jones (two of which, it should be noted, are from former clerks), just about all of the reactions I’ve received or seen online have been rather in line with mine—with one big exception: There’s been at least some criticism of me for agreeing to participate in Thursday’s event in the first place—dovetailing with the broader, ongoing debate over whether left-of-center academics should have any relationship with the Federalist Society. Judge Jones wouldn’t have been able to attack me, the logic goes, if I hadn’t agreed to participate.

I’ve had deeply conflicted views about this debate since its inception. On one hand, I totally understand the concern that, when folks like me choose to participate in these kinds of conversations, it gives them some additional legitimacy and/or visibility that they might not have without us. In what he might have thought was supposed to be an apology at the beginning of Friday’s plenary session, Reuter—the Fed Soc Senior VP and General Counsel—touched on this when, according to media reports, he gave “particular thanks” and “gratitude” to speakers he didn’t name, noting that “[w]e’re only able to have debate and discussion if we can get people of divergent views to join our convention,” and that “[w]e couldn’t stay true to our form without them.” Indeed, you can’t have a debating society without debaters.

On the other hand, there were quite a lot of people in the room (and, thanks entirely to Judge Jones’s behavior, who have now watched the video) who may now have different views not just about the specific topic at hand (judge-shopping), but also about the relative seriousness, or lack thereof, of various of the participants. Indeed, some of the messages I’ve received since Thursday have been to this exact effect. If part of my goal is to get folks who aren’t inclined to agree with me to nevertheless take seriously some of the substantive points I’m trying to make, that couldn’t and wouldn’t have happened Thursday without my being there. Judge Jones’s behavior, ironically, only helped in that regard.

What worries me is less what happened in the room on Thursday than what hasn’t happened since: Reuter’s elliptical and milquetoast comments Friday morning are the only public acknowledgment by the Federalist Society that anything even happened (and you’d be hard-pressed to know what if you didn’t have the context); and, without revealing the substance of our private correspondence (he’s free to do so if he wants), I’ll just say that neither he nor anyone else from the organization has been any more contrite over e-mail. I’ve written before about how oftentimes, the reaction to an episode is more revealing than the episode itself. So too, here.

I can’t (and wouldn’t deign to) tell anyone else what they should do. But for me, I think this puts a thumb on the scale against participating in national Federalist Society events for the near future—at least until and unless the Society wants to acknowledge that Judge Jones’s behavior was flatly inconsistent with the dialogue that the Society claims it intends to foster. You can say that you’re committed to the respectful exchange of competing viewpoints, but when that principle is quite loudly and publicly tested, it’s hard to believe you if you’re not going to to back it up. Four days later, that hasn’t happened here. The Federalist Society may be a “they,” rather than an “it,” but as an organization, it either thinks the respectful exchange of ideas is worth speaking out for or it doesn’t. Put another way, the Society invites people like me either because it wants its audiences to hear what we have to say or because it just wants to be able to say that it invited us. If we’re just going to be props, then it seems like we should pass.

I continue to feel differently about student-run Federalist Society events. Part of that is because I have pedagogical and other obligations to (all of) my students that I don’t have to others—both to those who are active in the organization and to those who attend its events. Part of that is because it wouldn’t be fair to hold against 2Ls and 3Ls decisions that national folks have made. And part of it is because I continue to think that, even if the Federalist Society isn’t going to back up its commitment to high-minded debate, there’s value in trying to model what it looks like—that isn’t as outweighed in the student-event context as it is for national events. It’s still ridiculous that the national organization will pay an honorarium to the conservative who I debate at student-run events but not to me (this is how many, if not most, student-run Fed Soc events work), but again, that’s not the students’ fault. And although there are some people who I won’t debate, that’s because of who they are, not because my students chose to invite them.

Of course, others may draw these lines differently, and that’s as it should be. All I can say is that this is what feels right to me.

V. Why All of this Matters

I wanted to write all of this not because I’m interested in the airing of grievances; my snarky asides … aside, I don’t think any of what I’ve said above has suggested anything about Judge Jones other than that she made a series of clumsy and not-factually-supported attacks against me.

Rather, I think that what happened Thursday is important because it is both (1) not unique; and (2) an alarming portent of what public debates over our government institutions may increasingly resemble in the coming years. With one party holding the reins of both elected branches of government and with justices appointed by presidents of that party holding a 6-3 majority on the Supreme Court, there will be an obvious temptation to dismiss any discussion of institutional reform in the coming years as partisan attacks designed to weaken Republicans and strengthen Democrats. (Indeed, this has been a frustrating feature of Supreme Court reform discussions for some time.)

This is why it is especially incumbent upon judges to not just resist perpetuating that view, but to actually lead the charge in defense of the principled exchange of opposing viewpoints—the epitome of what the practice of law is supposed to reflect. The point is not that judges are supposed to be emotionless automatons; it is that they are supposed to set an example for ensuring that serious arguments are taken seriously—even, if not especially, when they are rejected. To ignore those arguments in favor of efforts to attack and delegitimize those making them because of who they are is to reinforce charges that, to the judges acting that way, the law doesn’t actually matter; all that matters is who gets to wield the judicial power.

I wrote last week about Justice Robert Jackson’s view of the role of courts in checking the other institutions of government on the far side of his time as lead U.S. prosecutor at Nuremberg. It seems fitting to close this week with his view on the dangers of this kind of demonization of dissent—which he articulated in the middle of World War II in the celebrated opinion for the Court in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette: “As governmental pressure toward unity becomes greater, so strife becomes more bitter as to whose unity it shall be. . . . Those who begin coercive elimination of dissent soon find themselves exterminating dissenters. Compulsory unification of opinion achieves only the unanimity of the graveyard.”

If you’re not already a subscriber to “One First,” I hope you’ll consider becoming one. And if you are and your circumstances permit, I hope you’ll consider upgrading to a paid subscription:

Regardless, thank you for reading today’s issue of the newsletter. We’ll be back Thursday with this week’s bonus issue, and next Monday with our regular, much news-ier coverage of the Supreme Court.

Have a great week, everybody.

Indeed, the only example Judge Jones identified in which I said anything remotely pejorative was this tweet—in which the behavior I was describing (and criticizing) was when Kacsmaryk took his name off of a law review article after a student-run law review had accepted it—and just before he was nominated to the district court. Leaving aside that he wasn’t even a judge at that point, I described his behavior as “nonsense.”

With the exception of Joe Patrice at Above the Law, the media reports on the panel have been surprisingly (and, I’ll say, frustratingly) equivocal about the tenor of the exchange.

I can’t speak for anyone else, but if I was moderating a panel on which one member was personally attacking another, I would, you know, “moderate” it.

Just dropping a footnote to remind you that she didn’t.

With respect to section IV on participation in FedSoc (and similar) debates—

I really hope the takeaway is *more* individuals with solid, principled disagreements with FedSoc should participate. There is a real risk these panels will be populated by Alan Colmes types, as Epps said in his remarks. The FedSoc does not need a B team of law professor Washington Generals to dunk on.

I watched the whole exchange on Friday and...wow, Judge Jones did not come across well. I understand Vladeck's personal....irritation, to put it mildly. However, his presence AND participation on this panel helped draw a huge red circle around how weak the arguments made by Judge Jones really are. No fair-minded person can walk away from that video and think Judge Jones acquitted herself honorably OR that she made her point effectively. That was only possible because Vladeck was both there AND made HIS point without taking the bait.

So I'm thankful Vladeck participated and did so in an effective manner. Thank you.

This is very disturbing. I know it's the effing Federalist Society, but O Wow! The cloak of autocracy gets heavy very quickly. Very quickly.